Grigolia, Tamta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections 3 Reflections

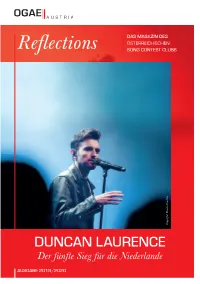

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Tele and Jury Incl Comments

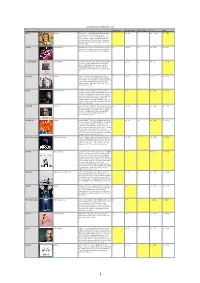

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Final My Placing Me guessing Final result Tele Jury Malta Michela Chameleon - I seriously think Malta is worth 8 11-15 16 22 - 20p 10 - 75p more this year. The recorded version of ”Chameleon” is a piece of brilliant pop but also honestly… They failed to bring it from recorded to live. The act looked a bit messy, but only 20 points from the tele voting? No that’s not fair. Albania Jonida Maliqi Ktheju tokes - I don´t have much to say here 18 16-20 18 17 - 47p 18 - 43p cause this is a kind of genre you only hear in the Eurovision and the result was expected. Czech Republic Lake Malawi Friend of a friend - This is one of the big WTF 20 21-26 11 24 - 7p 6 - 150p ´s on the night… What with the jury? 6th place really? What did the jury see in this entry? Will be fun to see how the diferent countries really voted in the breakdown later on. Germany S!sters Sister - I moved Germany from the last 6 17 21-26 24 26 - 0p 21 - 32p places up to 17 on the night cause the girls performed it well but the result was expected. I am actually surprised they got 32 points from the juries. But again one of the ”Big 5” failed a good result. Russia Sergey Lazarev Scream - A small surprise since I guessed 7 6-10 3 4 - 244p 9 - 125p Sergey would have been rewarded more in the tele votes than with the political jury voting. -

Sticonpoint June 2019 Edition

June 2019 Issue I am from the Everyone knows me by Maldives. I am International Students my nickname “Willy”. I studying Aeronautics am from Myawaddy, I am a seminarian Kayine, Myanmar. I am in this institution. I staying at Camillian like to swim and dive. 20 years old. I graduated Social Center from Sappawithakhom It’s a passion of mine Prachinburi. Right to explore the School. Before my now, I am studying graduation, I didn’t have underwater beauty. English courses with any idea where to study What I like most about the Business English and what major to take up. One day, Ajarn the college is the hospitality given to me students. I think this Korn Sinchai from STIC Marketing/ by each and everyone on the campus. It institution is good Guidance and Counseling Team introduced is grateful to have a friendly for learning English. St. Theresa International College to grade 12 environment with great personalities. There are many good teachers here and students in our school including myself. Mohamed Shamaail, the environment is a good place to stay. During his presentation, I realized that this is Aeronautics Y1 Nguyen Dinh Minh Quang, what I really want for my tertiary education. Business English Y1 Moreover, the college fees are not expensive My friends call me and I would have the chance to study with Rose. I am 18 years People call me Toby. I real professors. Then, I made the decision to old. I am a Filipino am a German citizen be here at STIC. but was born here in but I grew up in Aung Thu Rain Oo, Aeronautics Y1 Thailand. -

Kuwaittimes 14-5-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RAMADAN 9, 1440 AH TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2019 28 Pages Max 43º Min 25º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17832 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Assembly set to debate New Delhi hit by rare Liverpool seeking perfection 3 grilling against premier 24 ‘air pollution’ alert 27 in bid to dethrone Man City IMSAK 03:18 Fajr 03:28 Dhur 11:44 Asr 15:20 Magrib 18:32 Isha 19:59 Saudi tankers hit by ‘sabotage attacks’ as Gulf tensions soar Kuwait condemns the ‘criminal attack’ • UAE launches probe • Iran calls incident ‘worrisome’ DUBAI: Saudi Arabia said yesterday that two of its oil tankers were among those attacked off the coast of the United Arab Emirates and said it was an attempt to under- mine the security of crude supplies amid tensions between the United States and Iran. The UAE said on Sunday that four commercial vessels were sabotaged near Fujairah emirate, one of the world’s largest bunkering hubs lying just outside the Strait of Hormuz. It did not describe the nature of the attack or say who was behind it. The UAE had not given the nationalities or other details about the ownership of the four vessels. Riyadh has identi- fied two of them as Saudi and a Norwegian company said it owned another. Details of the fourth ship were not immediately clear. Thome Ship Management said its Norwegian-registered oil products tanker MT Andrew Victory was “struck by an unknown object”. Footage seen by Reuters showed a hole in the hull at the waterline with the metal torn open inwards. -

Europe's Biggest Party

Europe’s Pick the winning country for your chance to win a prize. Cross out any teams that have not got through to the final of Europe’s 1 biggest party. We suggest players pay a donation of £2 (no donation necessary) to put their biggest Party 2 name next to a country still in the running. Once the sheet is full and the money is in, wait for the winning country to be 3 revealed and give the winner their prize. The could be hald the donations of a United Kingdom Albania Armenia prize of your choosing. 4 The remaining money will go Breast Cancer Now to help us to make life- Michael Rice Jonida Maliqi Srbuk saving breast cancer research and life-changing support happen. Bigger Than Us Ktheju Tokës Walking Out Australia Austria Azerbaijan Belarus Belgium Kate Miller-Heidke PÆNDA Chingiz ZENA Eliot Zero Gravity Limits Truth Like It Wake Up Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Roko Tamta Lake Malawi Leonora Victor Crone The Dream Replay Friend of a Friend Love is forever Storm Finland France Georgia Germany Greece Darude Bilal Hassani Oto Nemsadze S!sters Katerine Duska feat. Sebastian Roi Keep on going Sister Better love Look away Hungary Iceland Ireland Israel Italy Joci Pápai Hatari Sarah McTernan Kobi Marimi Mahmood Az én apám Hatrio mun sigra 22 Home Soldi Latvia Lithuania Malta Moldova Montenegro Carousel Jurij Veklenko Michela Anna Odobescu D mol That Night Run with the lions Chameleon Stay Heaven Portugal North Macedonia Norway Poland Romania Tamara Todevska KEiiNO Tulia Conan Osiris Ester Peony Proud Spirit in the Sky Fire of love (Pali sie) Telemóveis On a Sunday Russia San Marino Serbia Slovenia Spain Sergey Lazarev Serhat Nevena Božovic Zala Kralj & Gašper Šantl Miki Scream Say Na Na Na Kruna Sebi La Venda Sweden Switzerland The Netherlands John Lundvik Luca Hanni Duncan Laurence Too late for love She got me Arcade breastcancernow.org Breast Cancer Now is a working name of Breast Cancer Care and Breast Cancer Now, a charity registered in England and Wales (1160558) and Scotland (SC045584).. -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Popbitch-Guide-To-Eurovision-2019

Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats Hello, Tel Aviv! Another year, another 40-odd songs from every corner of the continent (and beyond...) Yes, it’s Eurovision time once again – so here is your annual Popbitch guide to all of the greatest, gaudiest and god-awful gems that this year’s contest has to offer. ////////////////////////////////// Semi-Final 1.................3-21 Wobbling opera ghosts! Fiery leather fetishists! Atonal interpretive Portuguese dance! Tuesday’s semi-final is a mad grab-bag of weirdness – so if you have an appetite for the odd stuff, this is the semi for you... Semi-Final 2................23-42 Culture Club covers! Robot laser heart surgery! Norwegian grumble rapping! Thursday’s qualifier is a little more staid, but there’s going to plenty of it that makes it through to the grand final – so best to bone up on it all... The Big Six.................44-50 They’ve already paid their way into the final (so they’re not really that interesting until Saturday rolls around) but if you want to get ahead of the game, these are the final six... The Stats...................52-58 Diagrams, facts, information, theory. You want to impress your mates with absolutely useless knowledge about which sorts of things win? We’ve got everything you need... Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats SF1: At A Glance This year’s contest is frontloaded with the mad stuff, so if BDSM electro, gruff Georgian rock and high-flying operatics from a group of women on massive wobbly sticks are what you watch Eurovision for, you’ll want to make some time for Tuesday’s semi.. -

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 - Semi 1

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 - Semi 1 www.bjornnordlund.com Björn Nordlund - 10 maj 2019 EUROVISION SONG CONTEST 2019 SEMI 1 - WWW.BJORNNORDLUND.COM 1" Introduction So its finally time for my personal Formula 1, my take on the Olympics or if you want it to be the vote more important than the upcoming EU elections. The show we all love to hate and the opportunity to disagree on something that engage and still means nothing. You can discuss religion or politics and never speak to your ”friend” again but have different views on a song in Eurovision won’t change the friendship even if you actually think your friends lost it forever. Never forget that we discuss taste here and its individual so agree, disagree and enjoy. You who know me You who know me know that I have followed the Eurovision Song Contest every year since 1971, the year I actually remember I watched the contest for the first time and maybe the reason why I got stucked is up to the fact that my favorite song won that year. Monaco, Severine, ”Un banc, un Abre, une rue”. Since then Eurovision changed a lot and honestly not always to the better and there are rules and trends now in 2019 I don’t agree upon at all but to be fair to the participants and the songs the upcoming pages with comments are not taking this into account, its another discussion. On the upcoming pages you will find my view on the 2019 songs together with a guess on the results. -

Cumulative Extremism: a Misguided Narrative?

Cumulative extremism: a misguided narrative? Comparing interactions between anti-Islamists and radical Islamists in Norway and the UK Sofia Slang Lygren Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Political Science UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2019 Cumulative extremism: a misguided narrative? Comparing interactions between anti-Islamists and radical Islamists in Norway and the UK I © Sofia Slang Lygren 2019 Cumulative extremism: a misguided narrative? Sofia Slang Lygren http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University Of Oslo Word count: 30 543 II Abstract Recently, scholars, policy-makers and experts have applied the term cumulative extremism to describe an escalating conflict between radical Islamist and anti-Islamist groups in Britain. This thesis aims at reaching a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between the two adversary groups, identifying the underlying processes that drive the relationship. I propose an alternative concept to cumulative extremism that I have coined Reciprocal Intergroup Radicalisation (RIR) that I argue better captures the interactions between the adversary groups. The research question asks which mechanisms fuel or contain reciprocal intergroup radicalisation (RIR), and what conditions facilitate or obstruct these mechanisms from unfolding. Drawing from the social movement literature, I have developed a theoretical framework consisting of six mechanisms that either fuel or contain radicalisation of interactions between anti-Islamists and radical Islamists. I have combined a comparative analysis with process tracing, with Britain serving as a positive case and Norway as a negative case. Similar anti-Islamist and radical Islamist social movement organisations emerged around the same time in Britain and Norway, yet no violent interactions occurred in the latter case. -

ESC 2019 SEMI 1 Result

Semi Final 1 2019 Country Singer Song Comment My 10 to final Guessing Final 10 to pass to the final Cyprus Tamta Replay Cyprus ended up as last years runner up and they obviously liked it cause here is ”Fuego” part II or if you like ”Fuego (Replay version)”. We will most likely see an amazing show on stage to hide the fact that this is a song composed to win Eurovision. I feel a bit sorry for Cyprus to walk this lane knowing how many amazing songs they sent to the contest sounding Cyprus not sounding like it could be from anywhere in the world. Not a winner in my book and hopefully this is the song a jury will stop from winning. Montenegro D-Mol Heaven I will be really surprised if Montenegro manage to be top 10 in the semi this year. I kind of like it until the Balkan notes hit the song and try to give it an ethnic touch. But is it enough Balkan countries in the first semi final to put D-Mol top 10? Finland Darude feat Sebastian Look away It might be Finlands luck to end up in the first semifinal Rejman which honestly must be seen as an easy pass to the final on Saturday. I have nothing nice to say here, ”Look away” sound dated and not much of a song in there. For me this is a big no. Poland Tulia Pali Się [Fire Of Funny enough I don’t hate this song even if it is so far Love] from my comfort zone and in addition to what must be the best lyric line this year ”Sitting on an ice berg waiting for the sun” I must say that one song within this genre is OK. -

Backward Class and Politics of Reservation in India 1919-1947

BACKWARD CLASS AND POLITICS OF RESERVATION IN INDIA 1919-1947 NAIRANJANA RAYCHAUDHURY, M.A., M. Phil. A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS) UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 1994 9^. R2t3.V> aOCKTAKmG-2011 11293S CONTENTS Preface I Abbreviations VI Chapter I. Introduction : Genesis of the Policy of Reservation Chapter II. Montagu-Chelmsford Reform and Development of the Political Ideology of Caste 37 Chapter III. The Separatist Depressed Class Movement and the Indian Statutory Commission (1927) 83 Chapter IV The Scheme for Electoral Concessions Consensus through Disagreement-(1930-32) 130 Chapter V Towards a renewed claim for Separate Electorate and the variety of Colonial Response (1932-45) 196 Chapter VI. Election and the final acquiescence in a settlement (1946-1947) 236 Chapter VII. Conclusion 268 Appendix 281 Bibliography 296 PREFACE The problem of the Depressed Classes has in recent times reappeared as an embarrassing issue of Indian politics. Years ago I set out to work on the subject on a limited scale in course of preparation of a dissertation for my M.Phil, degree. My initial interest in the subject was further stimulated when the work was subsequently published. Then I got a Fellowship in the Department of History, University of North Bengal, which I must gratefully acknowledge here had enabled me to follow up investigation on the subject on a wider perspective covering the three eventful decades ending with the transfer of power to Indian hands. The period had witnessed our frequent experiments with the system of responsible government which was altogether unknown to the people of the colonies. -

On the Trail N°29

On the Trail The defaunation bulletin n°29. Events from the 1st April to the 30th June, 2020 Quarterly information and analysis report on animal poaching and smuggling Published on March 22, 2021 Original version in French 1 On the Trail n°29. Robin des Bois Carried out by Robin des Bois (Robin Hood) with the support of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, the Franz Weber Foundation and of the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, France reconnue d’utilité publique 28, rue Vineuse - 75116 Paris Tél : 01 45 05 14 60 www.fondationbrigittebardot.fr Non Governmental Organization for the Protection of Man and the Environment Since 1985 14 rue de l’Atlas 75019 Paris, France tel : 33 (1) 48.04.09.36 - fax : 33 (1) 48.04.56.41 www.robindesbois.org [email protected] Publication Director : Charlotte Nithart Editors-in-Chief: Jacky Bonnemains and Charlotte Nithart Art Directors : Charlotte Nithart and Jacky Bonnemains Coordination : Elodie Crépeau-Pons Writing : Jacky Bonnemains, Gaëlle Guilissen, Jean-Pierre Edin, Charlotte Nithart and Elodie Crépeau-Pons. Research, Assistant Editor : Gaëlle Guilissen, Flavie Ioos, Elodie Crépeau-Pons and Irene Torres Márquez. Cartography : Dylan Blandel and Nathalie Versluys Cover : Giant humphead wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) © Klaus Stiefel (CC BY-NC) English Translation : Robin des Bois Previous issues in English : http://www.robindesbois.org/en/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ Previous issues in French : http://www.robindesbois.org/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ On the Trail n°29. Robin des Bois 2 NOTE AND ADVICE TO READERS “On the Trail“, the defaunation magazine, aims to get out of the drip of daily news and to draw up every three months an organized and analyzed survey of poaching, smuggling and worldwide market of animal species protected by national laws and international conventions.