Tamta's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 Day Georgian Holidays Cultural & Sightseeing Tours

15 Day Georgian Holidays Cultural & Sightseeing Tours Overview Georgian Holidays - 15 Days/14 Nights Starts from: Tbilisi Available: April - October Type: Private multy-day cultural tour Total driving distance: 2460 km Duration: 15 days Tour takes off in the capital Tbilisi, and travels through every corner of Georgia. Visitors are going to sightsee major cities and towns, provinces in the highlands of the Greater and Lesser Caucasus mountains, the shores of the Black Sea, natural wonders of the West Georgia, traditional wine- making areas in the east, and all major historico-cultural monuments of the country. This is very special itinerary and covers almost all major sights in Tbilisi, Telavi, Mtskheta, Kazbegi, Kutaisi, Zugdidi, Mestia, and Batumi. Tour is accompanied by professional and experienced guide and driver that will make your journey smooth, informational and unforgettable. Preview or download tour description file (PDF) Tour details Code: TB-PT-GH-15 Starts from: Tbilisi Max. Group Size: 15 Adults Duration: 15 Days Prices Group size Price per adult Solo 3074 € 2-3 people 1819 € 4-5 people 1378 € 6-7 people 1184 € 8-9 people 1035 € 10-15 people 1027 € *Online booking deposit: 60 € The above prices (except for solo) are based on two people sharing a twin/double room accommodation. 1 person from the group will be FREE of charge if 10 and more adults are traveling together Child Policy 0-1 years - Free 2-6 years - 514 € *Online booking deposit will be deducted from the total tour price. As 7 years and over - Adult for the remaining sum, you can pay it with one of the following methods: Bank transfer - in Euro/USD/GBP currency, no later than two weeks before the tour starts VISA/Mastercard - in GEL (local currency) in Tbilisi only, before the tour starts, directly to your guide via POS terminal. -

Georgia Armenia Azerbaijan 4

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 317 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travell ers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well- travell ed team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. Stefaniuk, Farid Subhanverdiyev, Valeria OUR READERS Many thanks to the travellers who used Superno Falco, Laurel Sutherland, Andreas the last edition and wrote to us with Sveen Bjørnstad, Trevor Sze, Ann Tulloh, helpful hints, useful advice and interest- Gerbert Van Loenen, Martin Van Der Brugge, ing anecdotes: Robert Van Voorden, Wouter Van Vliet, Michael Weilguni, Arlo Werkhoven, Barbara Grzegorz, Julian, Wojciech, Ashley Adrian, Yoshida, Ian Young, Anne Zouridakis. Asli Akarsakarya, Simone -

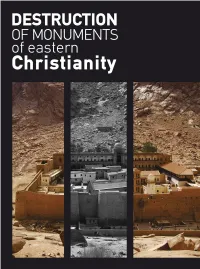

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

Post-Conference Event 5 Days Tour – 790 EUR Per Person (April 28-May 2, 2019)

Post-Conference Event 5 Days tour – 790 EUR per person (April 28-May 2, 2019) Day1: Yerevan, Geghard, Garni, Sevan, Dilijan, Dzoraget ✓ Breakfast at the hotel • Geghard Geghard Monastery is 40km south-east from Yerevan. Geghard Monastery carved out of a huge monolithic rock. Geghard is an incredible ancient Armenian monastery, partly carved out of a mountain. It is said that the Holy Lance that pierced the body of Christ was kept here. The architectural forms and the decoration of Geghard’s rock premises show that Armenian builders could not only create superb works of architecture out of stone, but also hew them in solid rock. It is included in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. • Garni From Geghard it is 11km to Garni Temple. Garni Pagan Temple, the only Hellenistic temple in the Caucasus. Gracing the hillside the temple was dedicated to the God of Sun, Mithra and comprises also royal palace ruins, Roman Baths with a well preserved mosaic. Lunch in Garni also Master class of traditional Armenian bread “lavash” being baked in tonir (ground oven). The preparation, meaning and appearance of traditional bread as an expression of culture in Armeniahas been inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. • Sevan Visit to Sevan Lake which is 80 km from Garni temple. Sevan Lake is the largest lake in Armenia and the Caucasus region. With an altitude of 1,900 meters above sea level, it’s one of the highest lakes in the world. The name Sevan is of Urartian origin, and is derived of Siuna, meaning county of lakes. -

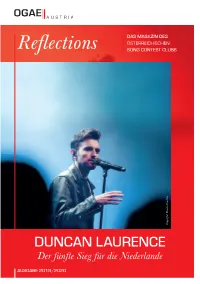

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL of KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N O 27 — 2017 2

1 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES N o 27 — 2017 2 E DITOR- IN-CHIEF David KOLBAIA S ECRETARY Sophia J V A N I A EDITORIAL C OMMITTEE Jan M A L I C K I, Wojciech M A T E R S K I, Henryk P A P R O C K I I NTERNATIONAL A DVISORY B OARD Zaza A L E K S I D Z E, Professor, National Center of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Alejandro B A R R A L – I G L E S I A S, Professor Emeritus, Cathedral Museum Santiago de Compostela Jan B R A U N (†), Professor Emeritus, University of Warsaw Andrzej F U R I E R, Professor, Universitet of Szczecin Metropolitan A N D R E W (G V A Z A V A) of Gori and Ateni Eparchy Gocha J A P A R I D Z E, Professor, Tbilisi State University Stanis³aw L I S Z E W S K I, Professor, University of Lodz Mariam L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emerita, Tbilisi State University Guram L O R T K I P A N I D Z E, Professor Emeritus, Tbilisi State University Marek M ¥ D Z I K (†), Professor, Maria Curie-Sk³odowska University, Lublin Tamila M G A L O B L I S H V I L I, Professor, National Centre of Manuscripts, Tbilisi Lech M R Ó Z, Professor, University of Warsaw Bernard OUTTIER, Professor, University of Geneve Andrzej P I S O W I C Z, Professor, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Annegret P L O N T K E - L U E N I N G, Professor, Friedrich Schiller University, Jena Tadeusz Ś W I Ę T O C H O W S K I (†), Professor, Columbia University, New York Sophia V A S H A L O M I D Z E, Professor, Martin-Luther-Univerity, Halle-Wittenberg Andrzej W O Ź N I A K, Professor, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw 3 PRO GEORGIA JOURNAL OF KARTVELOLOGICAL STUDIES No 27 — 2017 (Published since 1991) CENTRE FOR EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES FACULTY OF ORIENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW WARSAW 2017 4 Cover: St. -

Kvemo Kartli Üzrə

Müvəkkil 1 M№6 (12) İyun 2014 üvəkkil VƏTƏNDAŞ CƏMİYYƏTİ - CƏMİYYƏT MARAĞI AVROPA BİRLİYİ VƏ GÜRCÜSTAN- 2 ASOSİYASİYA HAQQINDA RAZILIQ- SUALLAR VƏ CAVABLAR YERLİ BƏLƏDİYYƏ VƏ RAYON İCRA 3 HAKİMİYYƏTİNƏ SEÇKİLƏR ƏRƏFƏSİNDƏ... NGOs ADDRESS TO THE SELF-REGULATORY 4 BODY OF KAVKASIA TV CHANNEL GÜRCÜSTAN AZƏRBAYCANLILARI 5 ALLAHIN ÜMİDİNƏ QALIB ГРУЗИНСКАЯ МЕЧТА АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНЦЕВ 6 2013-cü ildə Ümumi Səhiyyənin Qorunmasının Dövlət proqramının altkomponentləri ilə nəzərdə tutulmuş 7 xidmətin təşkil edilməsi üçün qeydiyyat haqqında ərizə formasının doldurulması və təqdim edilməsi qaydası KAXETİ BÖLGƏSİNDƏ SAQARECO RAYONUNU QARAÇÖP 8 MAHALINDA YAŞAYAN AZƏRBAYCANLILARIN SOSİAL-İQDİSADİ, MİLLİ-MƏNƏVİ VƏ TƏHSİL PROBLEMLƏRİNİN VƏZİYƏTİ SİYASİ PARTİYALARIN NAMİZƏDLƏR 9 HAQQINDA MƏLUMAT BORÇALI – KVEMO KARTLİ ÜZRƏ Majoritar namizədlər haqqında məlumat 18 Borçalı – Kvemo Kartli üzrə MRMG №12 Human Rights Monitoring Group of Ethnic Minorities 2 Müvəkkil AVROPA BİRLİYİ VƏ GÜRCÜSTAN-ASOSİYASİYA HAQQINDA RAZILIQ-SUALLAR VƏ CAVABLAR Razılıq Gürcüstana təklif edir: idarəçilik Doğrudurmu ki, “Asosiyasiya haqqında razılıq” standartlarını Avropa Birliyinin idarəçilik qüvvəyə minəndən sonra Avropa Birliyində təhsil standartları üzərində qursun, eləcədə Avropa Birliyi almaq mümkün olacaq? vətandaşlarımn olduğu kimi seçimləri olsun. Bu konkret məsələ razılıqda verilməyib. Ancaq, “Asosiyasiya haqqında razılıq” Gürcüstan Avropa Birliyinin maliyyəsi ilə artıq xüsusi demokratiyasına necə kömək edecək? ümumtəhsil proqramları fəaliyyət göstərir, hansı Razılıq deyir ki, Gürcüstan -

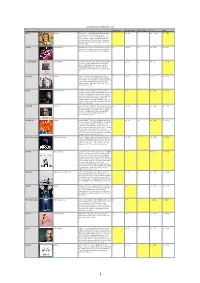

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Tele and Jury Incl Comments

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Final My Placing Me guessing Final result Tele Jury Malta Michela Chameleon - I seriously think Malta is worth 8 11-15 16 22 - 20p 10 - 75p more this year. The recorded version of ”Chameleon” is a piece of brilliant pop but also honestly… They failed to bring it from recorded to live. The act looked a bit messy, but only 20 points from the tele voting? No that’s not fair. Albania Jonida Maliqi Ktheju tokes - I don´t have much to say here 18 16-20 18 17 - 47p 18 - 43p cause this is a kind of genre you only hear in the Eurovision and the result was expected. Czech Republic Lake Malawi Friend of a friend - This is one of the big WTF 20 21-26 11 24 - 7p 6 - 150p ´s on the night… What with the jury? 6th place really? What did the jury see in this entry? Will be fun to see how the diferent countries really voted in the breakdown later on. Germany S!sters Sister - I moved Germany from the last 6 17 21-26 24 26 - 0p 21 - 32p places up to 17 on the night cause the girls performed it well but the result was expected. I am actually surprised they got 32 points from the juries. But again one of the ”Big 5” failed a good result. Russia Sergey Lazarev Scream - A small surprise since I guessed 7 6-10 3 4 - 244p 9 - 125p Sergey would have been rewarded more in the tele votes than with the political jury voting. -

The Oriental Institute 2013–2014 Annual Report Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2013–2014 annual repOrT oi.uchicago.edu © 2014 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN: 978-1-61491-025-1 Editor: Gil J. Stein Production facilitated by Editorial Assistants Muhammad Bah and Jalissa Barnslater-Hauck Cover illustration: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar from cylinder seal OIM A27903. Stone. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature various cylinder and stamp seals and sealings from different places and periods. Printed by King Printing Company, Inc., Winfield, Illinois, U.S.A. Overleaf: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar; and (above) black stone cylinder seal with modern impression. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm. OIM A27903. D. 000133. Photos by Anna Ressman oi.uchicago.edu contents contents inTrOducTiOn introduction. Gil J. Stein........................................................... 5 research Project rePorts Achemenet. Jack Green and Matthew W. Stolper ............................................... 9 Ambroyi Village. Frina Babayan, Kathryn Franklin, and Tasha Vorderstrasse ....................... 12 Çadır Höyük. Gregory McMahon ........................................................... 22 Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL). Scott Branting ..................... 27 Chicago Demotic Dictionary (CDD). François Gaudard and Janet H. Johnson . 33 Chicago Hittite and Electronic Hittite Dictionary (CHD and eCHD). Theo van den Hout ....... 35 Eastern Badia. Yorke Rowan.............................................................. 37 Epigraphic Survey. W. Raymond Johnson .................................................. -

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 6 Issue 4 2012 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Conflicts in the Caucasus: History, Present, and Prospects for Resolution Special Issue Volume 6 Issue 4 2012 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 6 Issue 4 2012 FOUNDEDTHE CAUCASUS AND& GLOBALIZATION PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 510 32 52 E-mail: [email protected] (IMANOV) Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 6 IssueMembers 4 2012 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. -

Il-Khans'system

The HistoricalSocietyHistorical Society of Japan Bagratid Kingdom. However, after the enthronement of Abaqa as the Il-Khan, Sadun received the titles of atabegi (or regent) and amir-spasarali (or commander in chief), and gained administrative E power over the Batratid Kingdom. He was entrusted by the Kings with the power to control the royal domains of T'elavi, Belakani and Kars. In addition, he purchased the district of Dmanisi from King Dimitri II. Together, Sadun's estates made up the fourth political unit in Georgian Armenia in addition to the three units belonging to the branch families of the Zak'areans. we can assume that he was able to acquire wealth because he was a・ t'arkhan, ・his After Sadtm's death in 1282, one bf two titles, the amir- spasarali was given to his son Khutlu-Bugha, but the other, the atabegi was given to his rival Tarsayichi of the house of Orbelean. In 1289, Khutlu-Bugha recommended that rl-Khan Arghun kill King Dimitri (who had been arrested for being implicated in the plot of Bugha) and put・Vakhtangi, the son of King Daviti IV on the throne. His plan succeeded. Under Vakhtangi, Khutlu-Bugha be- came both the atabegi and the amir-sPasarali and secured political ' power over the Georgian Kingdom. In 1292, however, both Arghun and Vakhtangi died. As soori as Daviti, the son of Dimitri, ascended to the throne, Khutlu- Bugha was put to death by the order of the new khan Geikhatu. With his death, the power of the Artsrunis was eradicated froni the entire Bagratid territory. -

Sticonpoint June 2019 Edition

June 2019 Issue I am from the Everyone knows me by Maldives. I am International Students my nickname “Willy”. I studying Aeronautics am from Myawaddy, I am a seminarian Kayine, Myanmar. I am in this institution. I staying at Camillian like to swim and dive. 20 years old. I graduated Social Center from Sappawithakhom It’s a passion of mine Prachinburi. Right to explore the School. Before my now, I am studying graduation, I didn’t have underwater beauty. English courses with any idea where to study What I like most about the Business English and what major to take up. One day, Ajarn the college is the hospitality given to me students. I think this Korn Sinchai from STIC Marketing/ by each and everyone on the campus. It institution is good Guidance and Counseling Team introduced is grateful to have a friendly for learning English. St. Theresa International College to grade 12 environment with great personalities. There are many good teachers here and students in our school including myself. Mohamed Shamaail, the environment is a good place to stay. During his presentation, I realized that this is Aeronautics Y1 Nguyen Dinh Minh Quang, what I really want for my tertiary education. Business English Y1 Moreover, the college fees are not expensive My friends call me and I would have the chance to study with Rose. I am 18 years People call me Toby. I real professors. Then, I made the decision to old. I am a Filipino am a German citizen be here at STIC. but was born here in but I grew up in Aung Thu Rain Oo, Aeronautics Y1 Thailand.