“Georgian Pride World Wide”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Monitoring the Implementation of the Code of Conduct by Political Parties in Georgia

REPORT MONITORING THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CODE OF CONDUCT BY POLITICAL PARTIES IN GEORGIA PREPARED BY GEORGIAN INSTITUTE OF POLITICS - GIP MAY 2021 ABOUT The Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) is a Tbilisi-based non-profit, non-partisan, research and analysis organization. GIP works to strengthen the organizational backbone of democratic institutions and promote good governance and development through policy research and advocacy in Georgia. It also encourages public participation in civil society- building and developing democratic processes. The organization aims to become a major center for scholarship and policy innovation for the country of Georgia and the wider Black sea region. To that end, GIP is working to distinguish itself through relevant, incisive research; extensive public outreach; and a bold spirit of innovation in policy discourse and political conversation. This Document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the GIP and can under no circumstance be regarded as reflecting the position of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. © Georgian Institute of Politics, 2021 13 Aleksandr Pushkin St, 0107 Tbilisi, Georgia Tel: +995 599 99 02 12 Email: [email protected] For more information, please visit www.gip.ge Photo by mostafa meraji on Unsplash TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 KEY FINDINGS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 METHODOLOGY 11 POLITICAL CONTEXT OF 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS AND PRE-ELECTION ENVIRONMENT -

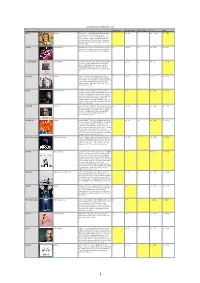

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Tele and Jury Incl Comments

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Final My Placing Me guessing Final result Tele Jury Malta Michela Chameleon - I seriously think Malta is worth 8 11-15 16 22 - 20p 10 - 75p more this year. The recorded version of ”Chameleon” is a piece of brilliant pop but also honestly… They failed to bring it from recorded to live. The act looked a bit messy, but only 20 points from the tele voting? No that’s not fair. Albania Jonida Maliqi Ktheju tokes - I don´t have much to say here 18 16-20 18 17 - 47p 18 - 43p cause this is a kind of genre you only hear in the Eurovision and the result was expected. Czech Republic Lake Malawi Friend of a friend - This is one of the big WTF 20 21-26 11 24 - 7p 6 - 150p ´s on the night… What with the jury? 6th place really? What did the jury see in this entry? Will be fun to see how the diferent countries really voted in the breakdown later on. Germany S!sters Sister - I moved Germany from the last 6 17 21-26 24 26 - 0p 21 - 32p places up to 17 on the night cause the girls performed it well but the result was expected. I am actually surprised they got 32 points from the juries. But again one of the ”Big 5” failed a good result. Russia Sergey Lazarev Scream - A small surprise since I guessed 7 6-10 3 4 - 244p 9 - 125p Sergey would have been rewarded more in the tele votes than with the political jury voting. -

Free, Fair and Equal Electoral-Political 2019-2022 Cycle in Georgia

Free, Fair and Equal Electoral-Political 2019-2022 Cycle in Georgia NEWSLETTER №15 December, 2020 Tbilisi, 2021 Supervisor: Vakhtang Menabde Author: Mariam Latsabidze This newsletter was made possible by the generous support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this newsletter are the sole responsibility of “Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association” (GYLA) and do not neces- sarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. INTRODUCTION In August 2019, the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA) has commenced implementation of the project “Free, Fair and Equal Electoral-Political 2019-2022 Cycle in Georgia”, which covers the area of Tbilisi, Kakheti, Mtskheta-Mtianeti, Kvemo Kartli, Shida Kartli, Imereti, Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti, Guria and Adjara. One of the goals of the project is to support improvement of the electoral environment through monitoring and evidence-based advocacy. To this end, the organization will monitor ongoing political processes and develop recommendations, which will be presented to the public and decision-makers. Post 2020 election developments Negotiations between the ruling party and the opposition Following the announcement of 2020 parliamentary elections results, the opposition rejected parliamentary mandates and committed themselves to the boycott.1 Their main requirements are as follows: new elections, resignation of CEC Chair and the release of the “political prisoners”.2 The disagreement between the opposition and the ruling party lead to a political crisis in the country.3 With the aim to overcome the crisis, through the assistance of facilitator Ambassadors, the parties have launched a negotiation process.4 Two rounds of negotiations were held on 12th and 14th of November.5 Despite the several rounds of negotiation, the parties failed to reach the agreement.6 On December 4, a multilateral meeting was held in the residence of the US Ambassador.7 According to the opposition leaders, they introduced a written proposal to the ambassadors. -

Sticonpoint June 2019 Edition

June 2019 Issue I am from the Everyone knows me by Maldives. I am International Students my nickname “Willy”. I studying Aeronautics am from Myawaddy, I am a seminarian Kayine, Myanmar. I am in this institution. I staying at Camillian like to swim and dive. 20 years old. I graduated Social Center from Sappawithakhom It’s a passion of mine Prachinburi. Right to explore the School. Before my now, I am studying graduation, I didn’t have underwater beauty. English courses with any idea where to study What I like most about the Business English and what major to take up. One day, Ajarn the college is the hospitality given to me students. I think this Korn Sinchai from STIC Marketing/ by each and everyone on the campus. It institution is good Guidance and Counseling Team introduced is grateful to have a friendly for learning English. St. Theresa International College to grade 12 environment with great personalities. There are many good teachers here and students in our school including myself. Mohamed Shamaail, the environment is a good place to stay. During his presentation, I realized that this is Aeronautics Y1 Nguyen Dinh Minh Quang, what I really want for my tertiary education. Business English Y1 Moreover, the college fees are not expensive My friends call me and I would have the chance to study with Rose. I am 18 years People call me Toby. I real professors. Then, I made the decision to old. I am a Filipino am a German citizen be here at STIC. but was born here in but I grew up in Aung Thu Rain Oo, Aeronautics Y1 Thailand. -

Anti-Liberal Populism and the Threat of Russian Influence in the Regions of Georgia

ANTI-LIBERAL POPULISM AND THE THREAT OF RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN THE REGIONS OF GEORGIA Liberal Academy Tbilisi Caucasus Research Resource Center Authors: Lasha Tughushi, Koba Turmanidze, Malkhaz Gagua, Tsitsino Khundadze, Guram Ananeishvili, Tinatin Zurabishvili. Reviewer: Davit Aprasidze Administrative Supervisor: Ana Tsikhelashvili Assistant: Elena Golashvili Translation: Tamar Rurua Proof reading: Dali Zhvelia Design by: Natia Sharabidze An anonymous reviewer assisted in finalizing the text. Published with the financial support of the Open Society Georgia Foundation. The views, opinions and statements expressed by the authors and those providing comments are theirs only and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foundation. Therefore, the Open Society Georgia Foundation is not responsible for the content of the information material. © European Initiative - Liberal Academy Tbilisi 50/1 Rustaveli av.,0108, Tbilisi, Georgia Tel/Fax: + (995 32) 293 11 28 Website http://www.ei-lat.ge Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 MAJOR FINDINGS 7 I. THE IMPACT OF CONSERVATIVE VIEWS ON THE PERCEPTION OF FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITIES AMONG THE GEORGIAN SPEAKING POPULATION IN KAKHETI AND SHIDA KARTLI 9 Foreign Policy Priorities of Kakheti and Shida Kartli Population 25 Portrait of pro-western individual 33 II. HOW DOES THE RUSSIAN NARRATIVE WORK? 42 Populism as a challenge to liberal democracy 46 Political myth as a tool for populism 51 How does myth work? 53 Myth of Katechon 55 Anti-liberal populism in Georgia’s mainstream politics, -

Narratives from Political Parties to Social Movements

GIP Policy Memo February 2020 / Issue #33 Deconstructing Modern Georgian Populism: Narratives from Political Parties to Social Movements Nino Samkharadze1 Introduction There has been a significant surge of populist rhetoric since 2012 within political-civil space, which is expressed in electoral success of populist parties and stirred up activities of populist social movements. According to the widely accepted definition, populism is a “thin” ideology that looks at the society as two homogenous and antagonist groups: “ordinary people” vs “corrupt elites” and in this “battle” the primary purpose of politics should be the expression of the people’s will2. The work analyses the Georgian populism though this framework. Multiple parties are considered to be populist within Georgian political circles, however, while selecting the subjects for the research, one parliamentary and one extra-parliamentary opposition parties with different ideologies were selected. Within the party spectrum “Alliance of Patriots of Georgia” have an increasing electoral support and currently occupies 6 sits in the Parliament3. Another populist “Georgian Labor Party”4 has been in politics since 1995 and did not get any mandates in the Parliament after the last parliamentary elections5, however, is active during the important political processes6. Besides parties, there are a number of movements among Georgian political circles with the purpose to mobilize masses and popularize their ideas within society. Since 2017 “Georgian March” 1 Junior Policy Analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics. 2 Mudde, C. (2004). The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition. pp. 541-563. 3 Liberal Academy Tbilisi, Caucasus Research Resource Center (May 29, 2019), Anti-Liberal Populism And The Threat of Russian Influence in The Regions of Georgia. -

Kuwaittimes 14-5-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RAMADAN 9, 1440 AH TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2019 28 Pages Max 43º Min 25º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17832 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Assembly set to debate New Delhi hit by rare Liverpool seeking perfection 3 grilling against premier 24 ‘air pollution’ alert 27 in bid to dethrone Man City IMSAK 03:18 Fajr 03:28 Dhur 11:44 Asr 15:20 Magrib 18:32 Isha 19:59 Saudi tankers hit by ‘sabotage attacks’ as Gulf tensions soar Kuwait condemns the ‘criminal attack’ • UAE launches probe • Iran calls incident ‘worrisome’ DUBAI: Saudi Arabia said yesterday that two of its oil tankers were among those attacked off the coast of the United Arab Emirates and said it was an attempt to under- mine the security of crude supplies amid tensions between the United States and Iran. The UAE said on Sunday that four commercial vessels were sabotaged near Fujairah emirate, one of the world’s largest bunkering hubs lying just outside the Strait of Hormuz. It did not describe the nature of the attack or say who was behind it. The UAE had not given the nationalities or other details about the ownership of the four vessels. Riyadh has identi- fied two of them as Saudi and a Norwegian company said it owned another. Details of the fourth ship were not immediately clear. Thome Ship Management said its Norwegian-registered oil products tanker MT Andrew Victory was “struck by an unknown object”. Footage seen by Reuters showed a hole in the hull at the waterline with the metal torn open inwards. -

Europe's Biggest Party

Europe’s Pick the winning country for your chance to win a prize. Cross out any teams that have not got through to the final of Europe’s 1 biggest party. We suggest players pay a donation of £2 (no donation necessary) to put their biggest Party 2 name next to a country still in the running. Once the sheet is full and the money is in, wait for the winning country to be 3 revealed and give the winner their prize. The could be hald the donations of a United Kingdom Albania Armenia prize of your choosing. 4 The remaining money will go Breast Cancer Now to help us to make life- Michael Rice Jonida Maliqi Srbuk saving breast cancer research and life-changing support happen. Bigger Than Us Ktheju Tokës Walking Out Australia Austria Azerbaijan Belarus Belgium Kate Miller-Heidke PÆNDA Chingiz ZENA Eliot Zero Gravity Limits Truth Like It Wake Up Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Roko Tamta Lake Malawi Leonora Victor Crone The Dream Replay Friend of a Friend Love is forever Storm Finland France Georgia Germany Greece Darude Bilal Hassani Oto Nemsadze S!sters Katerine Duska feat. Sebastian Roi Keep on going Sister Better love Look away Hungary Iceland Ireland Israel Italy Joci Pápai Hatari Sarah McTernan Kobi Marimi Mahmood Az én apám Hatrio mun sigra 22 Home Soldi Latvia Lithuania Malta Moldova Montenegro Carousel Jurij Veklenko Michela Anna Odobescu D mol That Night Run with the lions Chameleon Stay Heaven Portugal North Macedonia Norway Poland Romania Tamara Todevska KEiiNO Tulia Conan Osiris Ester Peony Proud Spirit in the Sky Fire of love (Pali sie) Telemóveis On a Sunday Russia San Marino Serbia Slovenia Spain Sergey Lazarev Serhat Nevena Božovic Zala Kralj & Gašper Šantl Miki Scream Say Na Na Na Kruna Sebi La Venda Sweden Switzerland The Netherlands John Lundvik Luca Hanni Duncan Laurence Too late for love She got me Arcade breastcancernow.org Breast Cancer Now is a working name of Breast Cancer Care and Breast Cancer Now, a charity registered in England and Wales (1160558) and Scotland (SC045584).. -

ČASOPIS PARALYMPIONIK POZOR! UŽ DNES Futbalisti, Nenapodobnite

Piatok 18. 6. 2021 75. ročník • číslo 139 cena 0,90 pre predplatiteľov 0,70 App Store pre iPad a iPhone / Google Play pre Android Výpravu našej futbalovej reprezentácie trápi Covidové starosti koronavírus, v karanténe sú Denis Vavro a člen realizačného tímu pred veľkým sviatkom Strany 2 – 10 a 19 – 20 FOTO TASR/ MARTIN BAUMANN Vavro: Keby zranenie, ale ozaj toto? 11 strán o Eure Tarkovič: Ťažko sa úplne odizolovať Aj napriek nepríjemným starostiam vládla na predzápasovom tréningu našej reprezentácie dobrá nálada. Futbalisti, nenapodobnite ich Takú nenávisť Bodaj by nie, vyzerá to tak, že už nikomu remíza so Švédmi nám s najväčšou Strana 24 pravdepodobnosťou bude stačiť Kým zverencov tréne- neželám na osemfinále. ra Štefana Tarkoviča FOTO TASR/MARTIN BAUMANN čaká na Eure zápas so Náš hokejový útočník Ma- Švédskom až dnes, xim Čajkovič sa v exkluzív- basketbalistky si zme- nom rozhovore pre denník rali sily s výberom Šport vracia k udalostiam, z tejto krajiny na ktoré smerovali k jeho vy- európskom šampionáte radeniu z kádra reprezentá- už včera. S prehrou cie do 20 rokov pred de- 57:74 nemohla byť cembrovými majstrovstvami spokojná ani Ivana sveta v Kanade. Jakubcová (s loptou). FOTO ŠPORT/MILAN ILLÍK FOTO TASR/FIBA Strana 23 ČASOPIS PARALYMPIONIK POZOR! UŽ DNES 2 NÁZORY piatok 18. 6. 2021 PRIAMA REČ VAHANA BIČACHČJANA Pozor na Isaka a Forsberga Slovensko bude dnes žiť druhým vy- práve fyzicky disponovaní futbalisti. „ Treba si dať pozor na štandardné posunie do osemfinále s najväčšou stúpením futbalovej reprezentácie na Hovorí sa, že Švédsko nemá individua- pravdepodobnosťou už remíza. Netre- Eure, ktorá si zmeria sily so Švédskom. -

11Th EFDN Conference Report CSR in European Football Hosted by KAA

th 11 EFDN Conference Report CSR in European Football Hosted by KAA Gent, Gent, Belgium 13-14 November 2018 1 Table of Contents KAA Gent Foundation .............................................................................................................................. 3 UEFA Equal Game – Celebrating Diversity and Inclusion in European Football ...................................... 4 DFB Foundation – Disability Football in Germany ................................................................................... 6 Breakout sessions #1: .............................................................................................................................. 8 1. Feyenoord Rotterdam – Fancoach Project ...................................................................................... 8 2. CSR in Eastern Europe ................................................................................................................... 10 a. Legia Warsaw – Karolina Kalinowska ............................................................................................ 10 b. Shakhtar Social – Yuriy Sviridov ..................................................................................................... 11 3. Aston Villa – Aston Villa CSR Strategy ‘Supporting our own’ ........................................................ 12 FC Barcelona Foundation – Sport for Development: the search of an Ethical ideal .............................. 14 Breakout sessions #2 ............................................................................................................................ -

GIP Krebuli Eng 2019.Indd

Compendium of Policy Briefs April 2019 The Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) is a Tbilisi-based non-profi t, non-partisan, research and analysis organization founded in early 2011. GIP strives to strengthen the organiza- tional backbone of democratic institutions and promote good governance and development through policy research and advocacy in Georgia. It also encourages public participation in civil society-building and developing democratic processes. Since December 2013 GIP is member of the OSCE Network of Think Tanks and Academic Institutions. *This publication has been produced from the resources provided by the National Endow- ment for Democracy. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessar- ily refl ect the views of the Georgian Institute of Politics and the National Endowment for Democracy. Editor: Kornely Kakachia Authors: Salome Minesashvili Levan Kakhishvili Bidzina Lebanidze Nino Robakidze Printed by: Grifoni © Georgian Institute of Politics, 2019 Tel: +995 599 99 02 12 Email: [email protected] www.gip.ge 3 FOREWORD Since the mid-2000s, democracy has regressed for Georgia’s democratization, hampering the in nearly every part of the world. The global establishment of a stable party system. The watchdog Freedom House1 has recorded de- 2018 presidential election was a clear example clines in global freedom for 12 years in a row. of the trust crisis and the extreme polarization Some states where democracy was believed to challenging Georgian democracy. While polit- be well-rooted have regressed under populist ical rivalry is part of any functioning democra- pressure with authoritarian tendencies. cy, in Georgia it has turned into polarization, rather than pluralism, limiting the public nar- While democracies have not collapsed, cur- rative and causing the fragmentation of the rent trends in global politics show that mod- political landscape, which is a major setback ern democracy is challenged by resurgent au- in the struggle to win back public trust.