Backward Class and Politics of Reservation in India 1919-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

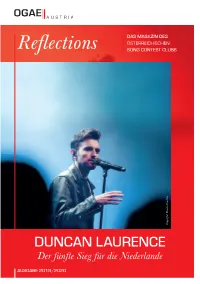

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

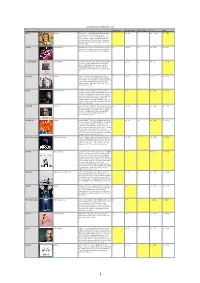

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Tele and Jury Incl Comments

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Final My Placing Me guessing Final result Tele Jury Malta Michela Chameleon - I seriously think Malta is worth 8 11-15 16 22 - 20p 10 - 75p more this year. The recorded version of ”Chameleon” is a piece of brilliant pop but also honestly… They failed to bring it from recorded to live. The act looked a bit messy, but only 20 points from the tele voting? No that’s not fair. Albania Jonida Maliqi Ktheju tokes - I don´t have much to say here 18 16-20 18 17 - 47p 18 - 43p cause this is a kind of genre you only hear in the Eurovision and the result was expected. Czech Republic Lake Malawi Friend of a friend - This is one of the big WTF 20 21-26 11 24 - 7p 6 - 150p ´s on the night… What with the jury? 6th place really? What did the jury see in this entry? Will be fun to see how the diferent countries really voted in the breakdown later on. Germany S!sters Sister - I moved Germany from the last 6 17 21-26 24 26 - 0p 21 - 32p places up to 17 on the night cause the girls performed it well but the result was expected. I am actually surprised they got 32 points from the juries. But again one of the ”Big 5” failed a good result. Russia Sergey Lazarev Scream - A small surprise since I guessed 7 6-10 3 4 - 244p 9 - 125p Sergey would have been rewarded more in the tele votes than with the political jury voting. -

Sticonpoint June 2019 Edition

June 2019 Issue I am from the Everyone knows me by Maldives. I am International Students my nickname “Willy”. I studying Aeronautics am from Myawaddy, I am a seminarian Kayine, Myanmar. I am in this institution. I staying at Camillian like to swim and dive. 20 years old. I graduated Social Center from Sappawithakhom It’s a passion of mine Prachinburi. Right to explore the School. Before my now, I am studying graduation, I didn’t have underwater beauty. English courses with any idea where to study What I like most about the Business English and what major to take up. One day, Ajarn the college is the hospitality given to me students. I think this Korn Sinchai from STIC Marketing/ by each and everyone on the campus. It institution is good Guidance and Counseling Team introduced is grateful to have a friendly for learning English. St. Theresa International College to grade 12 environment with great personalities. There are many good teachers here and students in our school including myself. Mohamed Shamaail, the environment is a good place to stay. During his presentation, I realized that this is Aeronautics Y1 Nguyen Dinh Minh Quang, what I really want for my tertiary education. Business English Y1 Moreover, the college fees are not expensive My friends call me and I would have the chance to study with Rose. I am 18 years People call me Toby. I real professors. Then, I made the decision to old. I am a Filipino am a German citizen be here at STIC. but was born here in but I grew up in Aung Thu Rain Oo, Aeronautics Y1 Thailand. -

Kuwaittimes 14-5-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RAMADAN 9, 1440 AH TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2019 28 Pages Max 43º Min 25º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17832 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Assembly set to debate New Delhi hit by rare Liverpool seeking perfection 3 grilling against premier 24 ‘air pollution’ alert 27 in bid to dethrone Man City IMSAK 03:18 Fajr 03:28 Dhur 11:44 Asr 15:20 Magrib 18:32 Isha 19:59 Saudi tankers hit by ‘sabotage attacks’ as Gulf tensions soar Kuwait condemns the ‘criminal attack’ • UAE launches probe • Iran calls incident ‘worrisome’ DUBAI: Saudi Arabia said yesterday that two of its oil tankers were among those attacked off the coast of the United Arab Emirates and said it was an attempt to under- mine the security of crude supplies amid tensions between the United States and Iran. The UAE said on Sunday that four commercial vessels were sabotaged near Fujairah emirate, one of the world’s largest bunkering hubs lying just outside the Strait of Hormuz. It did not describe the nature of the attack or say who was behind it. The UAE had not given the nationalities or other details about the ownership of the four vessels. Riyadh has identi- fied two of them as Saudi and a Norwegian company said it owned another. Details of the fourth ship were not immediately clear. Thome Ship Management said its Norwegian-registered oil products tanker MT Andrew Victory was “struck by an unknown object”. Footage seen by Reuters showed a hole in the hull at the waterline with the metal torn open inwards. -

Europe's Biggest Party

Europe’s Pick the winning country for your chance to win a prize. Cross out any teams that have not got through to the final of Europe’s 1 biggest party. We suggest players pay a donation of £2 (no donation necessary) to put their biggest Party 2 name next to a country still in the running. Once the sheet is full and the money is in, wait for the winning country to be 3 revealed and give the winner their prize. The could be hald the donations of a United Kingdom Albania Armenia prize of your choosing. 4 The remaining money will go Breast Cancer Now to help us to make life- Michael Rice Jonida Maliqi Srbuk saving breast cancer research and life-changing support happen. Bigger Than Us Ktheju Tokës Walking Out Australia Austria Azerbaijan Belarus Belgium Kate Miller-Heidke PÆNDA Chingiz ZENA Eliot Zero Gravity Limits Truth Like It Wake Up Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Roko Tamta Lake Malawi Leonora Victor Crone The Dream Replay Friend of a Friend Love is forever Storm Finland France Georgia Germany Greece Darude Bilal Hassani Oto Nemsadze S!sters Katerine Duska feat. Sebastian Roi Keep on going Sister Better love Look away Hungary Iceland Ireland Israel Italy Joci Pápai Hatari Sarah McTernan Kobi Marimi Mahmood Az én apám Hatrio mun sigra 22 Home Soldi Latvia Lithuania Malta Moldova Montenegro Carousel Jurij Veklenko Michela Anna Odobescu D mol That Night Run with the lions Chameleon Stay Heaven Portugal North Macedonia Norway Poland Romania Tamara Todevska KEiiNO Tulia Conan Osiris Ester Peony Proud Spirit in the Sky Fire of love (Pali sie) Telemóveis On a Sunday Russia San Marino Serbia Slovenia Spain Sergey Lazarev Serhat Nevena Božovic Zala Kralj & Gašper Šantl Miki Scream Say Na Na Na Kruna Sebi La Venda Sweden Switzerland The Netherlands John Lundvik Luca Hanni Duncan Laurence Too late for love She got me Arcade breastcancernow.org Breast Cancer Now is a working name of Breast Cancer Care and Breast Cancer Now, a charity registered in England and Wales (1160558) and Scotland (SC045584).. -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Telangana State Public Service Commission: Hyderabad Notification No

TELANGANA STATE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION: HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO. 10/2016 ASSISTANT HYDROLOGIST IN GROUND WATER DEPARTMENT (GENERAL RECRUITMENT) PARA – I: 1) Applications are invited Online from qualified candidates through the proforma Application to be made available on Commission’s WEBSITE (www.tspsc.gov.in ) to the post of Assistant Hydrologist in Ground Water Department in the State of Telangana. i. Submission of ONLINE applications from Dt. 22/05/2016 ii. Last date for submission of ONLINE applications Dt. 10/06/2016 iii. Hall Tickets can be downloaded 07 days before commencement of Examination. 2) The Examination is likely to be held on Dt. 28/06/2016. The Commission reserves the right to conduct the Examination either COMPUTER BASED RECRUITMENT TEST (CBRT) or OFFLINE OMR based examination of objective type. Before applying for the posts, candidates shall register themselves as per the One Time Registration (OTR) through the Official Website for TSPSC. Those who have registered in OTR already, shall apply by login to their profile using their TSPSC ID and Date of Birth as provided in OTR. 3) The candidates who possess requisite qualification may apply online by satisfying themselves about the terms and conditions of this recruitment. The details of vacancies are given below:- Age as on No. of Scale of Pay Sl.No. Name of the Post 01/07/2016 Vacancies Rs. Min. Max. Assistant Hydrologist in Ground Water 37,100 - 01 09 18-44* Department 91,450/- (The Details of Vacancies department wise i.e., Community, Zone Wise and Gender wise (General / Women) may be seen at Annexure-I.) IMPORTANT NOTE : The number of vacancies and Departments are subject to variation on intimation being received from the appointing authority. -

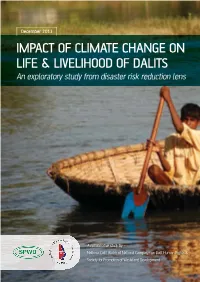

Impact of Climate Change on Life & Livelihood of Dalits

December 2013 IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON LIFE & LIVELIHOOD OF DALITS An exploratory study from disaster risk reduction lens A collaborative study by - National Dalit Watch of National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights & Society for Promotion of Wasteland Development IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON LIFE & LIVELIHOOD OF DALITS An exploratory study from disaster risk reduction lens A collaborative study by - National Dalit Watch of National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights & Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development December 2013 Design and Print: Aspire Design | aspiredesign.in Cover Photo: Amal Manikkath / sxc TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE ORGANISATIONS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Dalit stakes in environment are high 1 1.2 Dalit environmentalism 2 2. STUDY BACKGROUND 3 3. IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE 5 3.1 Impact of climate change on agriculture 6 4. IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON DISASTERS 8 5. INSTITUTIONAL SET-UP FOR DISASTER MANAGEMENT 10 6. INSTITUTIONAL SET-UP FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION 12 7. THE NEED FOR CONVERGENCE BETWEEN DRR AND CCA AND INCLUSION OF DALITS 14 8. CASE STUDIES 16 8.1. Case study: Assam 16 8.1.1 The problem of fl oods in Assam 16 8.1.2 Floods in the Brahmaputra valley 17 8.1.3 Flood affected communities in Dhemaji 18 8.1.4 Does climate change have a bearing on the occurrence and intensity of fl oods in Assam? 19 8.1.5 Adapting to climate change in agriculture in the fl ood plains of Brahmaputra, Assam 20 8.1.6 Erosion poses a greater threat than fl oods 21 8.1.7 Adapting to climate change effects in fl ood-prone areas in Dhemaji 23 8.1.8 Conclusion and policy implications 25 8.2. -

Andhra Pradesh Public Service Commission

1 ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION: HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO.22/2016, Dt.17/12/2016 CIVIL ASSISTANT SURGEONS IN A.P.INSURANCE MEDICAL SERVICE (GENERAL RECRUITMENT) PARA – 1: Applications are invited On-line for recruitment to the post of Civil Assistant Surgeons in A.P. Insurance Medical Service. The proforma Application will be available on Commission’s Website (www.psc.ap.gov.in) from 23/12 /2016 to 22/01/2017 (Note:22/01/2017 is the last date for payment of fee up- to 11:59 mid night). Before applying for the post, an applicant shall register his/her bio-data particulars through One Time Profile Registration (OTPR) on the Commission Website viz., www.psc.ap.gov.in. Once applicant registers his/her particulars, a User ID is generated and sent to his/her registered mobile number and email ID. Applicants need to apply for the post using the OTPR User ID through Commission’s website. The Commission conducts Screening test in Off - Line mode in case applicants exceed 25,000 in number and main examination in On-Line mode for candidates selected in screening test. If the screening test is to be held, the date of screening test will be communicated through Commission’s Website. The Main Examination is likely to be held On-Line through computer based test on 03/03/2017 FN & AN. There would be objective type questions which are to be answered on computer system. Instructions regarding computer based recruitment test are attached as Annexure - III. MOCK TEST facility would be provided to the applicants to acquaint themselves with the computer based recruitment test. -

Popbitch-Guide-To-Eurovision-2019

Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats Hello, Tel Aviv! Another year, another 40-odd songs from every corner of the continent (and beyond...) Yes, it’s Eurovision time once again – so here is your annual Popbitch guide to all of the greatest, gaudiest and god-awful gems that this year’s contest has to offer. ////////////////////////////////// Semi-Final 1.................3-21 Wobbling opera ghosts! Fiery leather fetishists! Atonal interpretive Portuguese dance! Tuesday’s semi-final is a mad grab-bag of weirdness – so if you have an appetite for the odd stuff, this is the semi for you... Semi-Final 2................23-42 Culture Club covers! Robot laser heart surgery! Norwegian grumble rapping! Thursday’s qualifier is a little more staid, but there’s going to plenty of it that makes it through to the grand final – so best to bone up on it all... The Big Six.................44-50 They’ve already paid their way into the final (so they’re not really that interesting until Saturday rolls around) but if you want to get ahead of the game, these are the final six... The Stats...................52-58 Diagrams, facts, information, theory. You want to impress your mates with absolutely useless knowledge about which sorts of things win? We’ve got everything you need... Semi Final 1 Semi Final 2 The Big Six The Stats SF1: At A Glance This year’s contest is frontloaded with the mad stuff, so if BDSM electro, gruff Georgian rock and high-flying operatics from a group of women on massive wobbly sticks are what you watch Eurovision for, you’ll want to make some time for Tuesday’s semi.. -

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 - Semi 1

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 - Semi 1 www.bjornnordlund.com Björn Nordlund - 10 maj 2019 EUROVISION SONG CONTEST 2019 SEMI 1 - WWW.BJORNNORDLUND.COM 1" Introduction So its finally time for my personal Formula 1, my take on the Olympics or if you want it to be the vote more important than the upcoming EU elections. The show we all love to hate and the opportunity to disagree on something that engage and still means nothing. You can discuss religion or politics and never speak to your ”friend” again but have different views on a song in Eurovision won’t change the friendship even if you actually think your friends lost it forever. Never forget that we discuss taste here and its individual so agree, disagree and enjoy. You who know me You who know me know that I have followed the Eurovision Song Contest every year since 1971, the year I actually remember I watched the contest for the first time and maybe the reason why I got stucked is up to the fact that my favorite song won that year. Monaco, Severine, ”Un banc, un Abre, une rue”. Since then Eurovision changed a lot and honestly not always to the better and there are rules and trends now in 2019 I don’t agree upon at all but to be fair to the participants and the songs the upcoming pages with comments are not taking this into account, its another discussion. On the upcoming pages you will find my view on the 2019 songs together with a guess on the results. -

35358 1961 MAD.Pdf

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II, PART V-B,.(12) ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ANDHRA PRADESH Preliminary B. SATYANARAYANA, ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES Investigation Investigator, on and draft: Office of the Directm' of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh SCHEDULED CASTES Supplementary P. LALITHA, I. Madiga Notes and revised Statistical Assistant, 2. Jambuvulu draft: Office of the Director of Census Operations, 3. Jaggali Andhra Pradesh 4 . .Arundhatiya Field Guidance P. S. R. AVADHANY, 5. Chalavadi and Supervisi9n: Deputy D:rector of Census Operatiom, 6. Chamar, Mochi or Muchi Andhra Pradesh 7. Samagara Editors: B. K.. Roy BURMAN, 8. Chambhar Deputy Registrar General, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India P. S. R. AVADHANY, Deputy Director of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh A. M. KURUP, Re3earch Officer, Office of the Office of the Registmf General, Director of Census Operations, India. Andhra Pradesh, HydC'rnbf/.d: 1-~ Cen. And.!71 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Cen.;us Publications of this State bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A General Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART I-C Sub3idiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART U-B (i) • Economic Tables (B-1 to B-IV) PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables (B-V to B-1 X) PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tabfes PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Sub~idiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and E~tablishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B *Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs (31) PART VII-A (1) }.