The Impact of Positive Discrimination in Education in India: Evidence From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A ,JUSTIFICATION of RESERVATION Forobcs (A CRI1''ique of SHO:URIE & ORS.)

GEN. EDITOR: DR. A. R. DESAI A ,JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATION FOROBCs (A CRI1''IQUE OF SHO:URIE & ORS.) MIHIRDESAI C.G. SHAll !\IE!\lORIAL TRUST PUBLICATION (20) C. G. Shah Memorial Trust Publication (20) A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOR OBCs by MIHIR DESAI Gen. EDITOR DR. A. R. DESAI. IN COLLABORATION WITH HUMAN RIGHTS & LAW NETWORK BOMBAY. DECEMBER 1990 C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Bombay. · Distributors : ANTAR RASHTRIY A PRAKASHAN *Nambalkar Chambers, *Palme Place, Dr. A. R. DESAI, 2nd Floor, Calcutta-700 019 * Jaykutir, Jambhu Peth, (West Bengal) Taikalwadi Road, Dandia Bazar, · Mahim P.O., Baroda - 700 019 Bombay - 400 016 Gujarat State. * Mihir Desai Engineer House, 86, Appollo Street, Fort, Bom'Jay - 400 023. Price: Rs. 9 First Edition : 1990. Published by Dr. A. K. Desai for C. G. Shah Memorial Trust, Jaykutir, T.:;.ikaiwadi Road, Bombay - 400 072 Printed by : Sai Shakti(Offset Press) Opp. Gammon H::>ust·. Veer Savarkar Marg, Prabhadevi, Bombay - 400 025. L. A JUSTIFICATION OF RESERVATIONS FOROOCs i' TABLE OF CONTENTS -.-. -.-....... -.-.-........ -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. S.No. Particulars Page Nos. -.- ..... -.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-.-. 1. Forward (i) - (v) 2. Preface (vi) - 3. Introduction 1 - 3 4. The N.J;. Government and 3 - 5' Mandai Report .5. Mandai Report 6 - 14 6. The need for Reservation 14 - 19 7. Is Reservation the Answer 19 - 27 8. The 10 Year time-limit .. 28 - 29 9. Backwardness of OBCs 29 - 39 10. Socia,l Backwardness and 39 - 40' Reservations 11. ·Criteria .for Backwardness 40 - 46 12. lnsti tutionalisa tion 47 - 50 of Caste 13. Economic Criteria 50 - 56 14. The Merit Myth .56 - 64 1.5. -

3.029 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal IJMSRR E- ISSN

Research Paper IJMSRR Impact Factor: 3.029 E- ISSN - 2349-6746 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2349-6738 DALITS IN TRADITIONAL TAMIL SOCIETY K. Manikandan Sadakathullah Appa College, Tirunelveli. Introduction ‘Dalits in Traditional Tamil Society’, highlights the classification of dalits, their numerical strength, the different names of the dalits in various regions, explanation of the concept of the dalit, origin of the dalits and the practice of untouchabilty, the application of distinguished criteria for the dalits and caste-Hindus, identification of sub-divisions amongst the dalits, namely, Chakkiliyas, Kuravas, Nayadis, Pallars, Paraiahs and Valluvas, and the major dalit communities in the Tamil Country, namely, Paraiahs, Pallas, Valluvas, Chakkilias or Arundathiyars, the usage of the word ‘depressed classes’ by the British officials to denote all the dalits, the usage of the word ‘Scheduled Castes’ to denote 86 low caste communities as per the Indian Council Act of 1935, Gandhi’s usage of the word ‘Harijan’ to denote the dalits, M.C. Rajah’s opposition of the usage of the word ‘Harijan’, the usage of the term ‘Adi-Darvida’ to denote the dalits of the Tamil Country, the distribution of the four major dalit communities in the Tamil Country, the strength of the dalits in the 1921 Census, a brief sketch about the condition of the dalits in the past, the touch of the Christian missionaries on the dalits of the Tamil Country, the agrestic slavery of the dalits in the modern Tamil Country, the patterns of land control, the issue of agrestic servitude of dalits, the link of economic and social developments with the changing agrarian structure and the subsequent profound impact on the lives of the Dalits and the constructed ideas of native super-ordination and subordination which placed the dalits at the mercy of the dominant communities in Tamil Society’. -

Aump Mun 3.0 All India Political Parties' Meet

AUMP MUN 3.0 ALL INDIA POLITICAL PARTIES’ MEET BACKGROUND GUIDE AGENDA : Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century Letter from the Executive Board Greetings Members! It gives us immense pleasure to welcome you to this simulation of All India Political Parties’ Meet at Amity University Madhya Pradesh Model United Nations 3.0. We look forward to an enriching and rewarding experience. The agenda for the session being ‘Comprehensively analysing the reservation system in the light of 21st century’. This study guide is by no means the end of research, we would very much appreciate if the leaders are able to find new realms in the agenda and bring it forth in the committee. Such research combined with good argumentation and a solid representation of facts is what makes an excellent performance. In the session, the executive board will encourage you to speak as much as possible, as fluency, diction or oratory skills have very little importance as opposed to the content you deliver. So just research and speak and you are bound to make a lot of sense. We are certain that we will be learning from you immensely and we also hope that you all will have an equally enriching experience. In case of any queries feel free to contact us. We will try our best to answer the questions to the best of our abilities. We look forward to an exciting and interesting committee, which should certainly be helped by the all-pervasive nature of the issue. Hopefully we, as members of the Executive Board, do also have a chance to gain from being a part of this committee. -

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India

The Effectiveness of Jobs Reservation: Caste, Religion and Economic Status in India Vani K. Borooah, Amaresh Dubey and Sriya Iyer ABSTRACT This article investigates the effect of jobs reservation on improving the eco- nomic opportunities of persons belonging to India’s Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST). Using employment data from the 55th NSS round, the authors estimate the probabilities of different social groups in India being in one of three categories of economic status: own account workers; regu- lar salaried or wage workers; casual wage labourers. These probabilities are then used to decompose the difference between a group X and forward caste Hindus in the proportions of their members in regular salaried or wage em- ployment. This decomposition allows us to distinguish between two forms of difference between group X and forward caste Hindus: ‘attribute’ differences and ‘coefficient’ differences. The authors measure the effects of positive dis- crimination in raising the proportions of ST/SC persons in regular salaried employment, and the discriminatory bias against Muslims who do not benefit from such policies. They conclude that the boost provided by jobs reservation policies was around 5 percentage points. They also conclude that an alterna- tive and more effective way of raising the proportion of men from the SC/ST groups in regular salaried or wage employment would be to improve their employment-related attributes. INTRODUCTION In response to the burden of social stigma and economic backwardness borne by persons belonging to some of India’s castes, the Constitution of India allows for special provisions for members of these castes. -

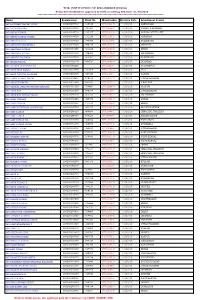

THE INSTITUTION of ENGINEERS (INDIA) Newly Elected Members Approved by ICNC at Metting 208 Date: 31/10/2018 ======

THE INSTITUTION OF ENGINEERS (INDIA) Newly Elected Members approved by ICNC at metting 208 Date: 31/10/2018 ===================================================================================================== Name Registration Draft No Membership Election Date Attachment Centre MS A ESTHER SALOMY DOSS 180200297740 149016 ST711928-9 31/10/18 KARNATAKA MS AATIRA BASHIR 180200302310 317361 ST712064-3 31/10/18 JAMMU & KASHMIR MR ABHAY KUMAR 180200297540 134547 ST711910-6 31/10/18 BOKARO STEEL CITY MR ABHAY KUMAR VERMA 180200304520 181210 ST712145-3 31/10/18 VARANASI MR ABHINAND V V 180200304720 748798 ST712159-3 31/10/18 KOZHIKODE MR ABHISHEK BHARDWAJ 180200300460 998149 ST712023-6 31/10/18 ALIGARH MR ABHISHEK KUMAR 180200301090 431446 ST712040-6 31/10/18 DELHI MR ABHISHEK YADAV 180200303430 329394 ST712106-2 31/10/18 ALLAHABAD MR ABIJITH KOORARA 180200297730 000581 ST711927-0 31/10/18 KOZHIKODE MS ABREZ HEYRA 180200302370 894723 ST712069-4 31/10/18 DHANBAD MR ADARSH KUMAR PATWA 180208792260 ST712207-7 31/10/18 GORAKHPUR MR ADUR RIAZ ISMAIL 180200302790 541855 ST712103-8 31/10/18 GOA MS AHER GAYATRI RAJARAM 180200299800 023869 ST711982-3 31/10/18 NASHIK MR AJEET KUMAR TIWARI 180200302610 809752 ST712087-2 31/10/18 UTTAR PRADESH MR AKASH TRIPATHI 180200301890 983023 ST712055-4 31/10/18 JABALPUR MR AKHARE ANKUSH HARISHCHANDRA 180200301720 070663 ST712044-9 31/10/18 NAGPUR MR AKHILESH 180200305100 846554 ST712188-7 31/10/18 UTTARAKHAND MR AKHILESH KUMAR YADAV 180200299500 503223 ST711974-2 31/10/18 ALLAHABAD MR AMAL NASKAR 180200302660 269079 -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan

PRG 335 (N) 1,000 ETHNOGRAPHIC ATLAS OF RAJASTHAN (WITH REFERENCE TO SCHEDULED CASTES & SCHEDULED TRIBES) U.B. MATHUR OF THE RAJASTHAN STATISTICAL SERVICE Deputy Superintendent of Census Operations, Rajasthan. GANDHI CENTENARY YEAR 1969 To the memory of the Man Who spoke the following Words This work is respectfully Dedicated • • • • "1 CANNOT CONCEIVE ANY HIGHER WAY OF WORSHIPPING GOD THAN BY WORKING FOR THE POOR AND THE DEPRESSED •••• UNTOUCHABILITY IS REPUGNANT TO REASON AND TO THE INSTINCT OF MERCY, PITY AND lOVE. THERE CAN BE NO ROOM IN INDIA OF MY DREAMS FOR THE CURSE OF UNTOUCHABILITy .•.. WE MUST GLADLY GIVE UP CUSTOM THAT IS AGA.INST JUSTICE, REASON AND RELIGION OF HEART. A CHRONIC AND LONG STANDING SOCIAL EVIL CANNOT BE SWEPT AWAY AT A STROKE: IT ALWAYS REQUIRES PATIENCE AND PERSEVERANCE." INTRODUCTION THE CENSUS Organisation of Rajasthan has brought out this Ethnographic Atlas of Rajasthan with reference to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. This work has been taken up by Dr. U.B. Mathur, Deputy Census Superin tendent of Rajasthan. For the first time, basic information relating to this backward section of our society has been presented in a very comprehensive form. Short and compact notes on each individual caste and tribe, appropriately illustrated by maps and pictograms, supported by statistical information have added to the utility of the publication. One can have, at a glance. almost a complete picture of the present conditions of these backward communities. The publication has a special significance in the Gandhi Centenary Year. The publication will certainly be of immense value for all official and Don official agencies engaged in the important task of uplift of the depressed classes. -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) --~92f---- CENSUS O}-' INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 oP. or 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 0 .. z 0", '" o~ Z '" ::::::::::::::::3i=:::::::::=:_------_:°i-'-------------------T~ uJ ~ :2 I I I .,0 ..rtJ . I I I I . ..,N I 0-t,... 0 <I °...'" C/) oZ C/) ?!: o - UJ z 0-t 0", '" '" Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-} CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAl- GoVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-:Gujatat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Eep8rt 1-·B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I~C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables n-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-lV-C) II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) Il-C Cultural and Migration Tables IU Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Seleted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Fest,ivals VIlI-A Administration Report-EnumeratiOn) Not for Sale VllI-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CO NTF;N'TS Table Pages Note 1- 6 SCT-I PART-A Industrial Classification of Persons at Work and Non·workers by Sex for Scheduled Castes . -

Proposed Date

First Name Father/Husba Address Country State PINCode Folio Number of Securities Amount Proposed Date of nd First Name Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) ZUBEENA MONEM NA XXX XXX XX INDIA Andhra Pradesh 999999 0000000000CEZ0018034 214.50 01-AUG-2013 ZUBEDA BEN GANDHI NA NAVA PARA NATHI BAI MASJID JAMNAGAR GUJARATINDIA Gujarat 361001 0000000000CEZ0018028 279.50 01-AUG-2013 ZUBEDA ASHRAF NA 44/315 MESTON ROAD KANPUR INDIA Uttar Pradesh 202001 0000000000CEZ0018027 214.50 01-AUG-2013 ZENI ABID KAGALWALA NA 95 NAVRANG PEDDAR ROAD BOMBAY INDIA Maharashtra 400026 0000000000CEZ0018020 104.00 01-AUG-2013 ZACHARIAH G PUNNACHALILNA THIRUVANKULAM PO ERNAKULAM DIST KERALA INDIA Kerala 682305 0000000000CEZ0018002 13.50 01-AUG-2013 YOGESH MANUBHAI DESAINA 42 G D AMBEKAR ROAD 202 INDIA PRINTING HOUSEINDIA WADALAMaharashtra BOMBAY 400031 0000000000CEY0018087 539.50 01-AUG-2013 YOGESH KAMANI NA PRAKASH NO 1 BLOCK NO 3 28 B G KHAR MARG BOMBAYINDIA Maharashtra 400006 0000000000CEY0018084 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YOGENDRA PRASAD NA C/O B N RAY LIC BR 2 PODHANSAR DHANBAD INDIA Jharkhand 826001 0000000000CEY0018069 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YERRAM GOPAL REDDY NA PLOT NO 34 H NO 27-64/5/2/1/A SRI KRISHNA NAGARINDIA - WESTAndhra POST- Pradesh R K PURAM 500056SECUNDRABAD0000000000CEY0018061 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YELAMANCHILI SWARNALATHANA 8-3-214/13 SRINIVAS NAGAR WEST VENGAL RAO INDIANAGAR POSTAndhra HYDERABAD Pradesh 500038 0000000000CEY0018060 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YASHWIN T KHATTAN NA C/O INDUSTO PLAST 138 ADHYARA IND ESTATE SUNINDIA MILL MaharashtraCOMPOUND LOWR PAREL400013 -

The Educational Problems Op Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe School and College Students in India

THE EDUCATIONAL PROBLEMS OP SCHEDULED CASTE AND SCHEDULED TRIBE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE STUDENTS IN INDIA (A Statistical Profile) Prepared for the Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi - By VIMAL P.SHAH Department of Sociology, Gujarat University, AHMEDABAD. NIEPA DC IH lllllll D00434 1975 CENTRE FOR REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, Post Box No 38, Dangore Street, Nanpura, SURAT : 395 001 G U J A R A T T ... U cw Delhi-llOOlT MEMBERS OF CO-ORDINATING COMMITTEE 1. Yogesh Atal 2. Ajit K. Danda 3. Ramkrishna Mukherjee 4. Vimal P* Shah 5. Yogendra Singh 6# Suma Ctiitnis Jt. Convener ?. I. P. Besai Convener PREFACE The Indian Council of Social Science Research brought together a group of social scientists from all over the country to design and execute a nation wide study of the~educational problems of high school and college students belonging to the sche duled castes and tribes. For this purpose, the ICSSR constituted a Co-ordinating Committee, and charged it with the task of designing and executing the study with the help of several other social scientists selected as project directors in diffe rent states. The major responsibility of the Co ordinating Committee was to articulate the research problem, to design sampling plan, to construct the instrument for data-collection, to centrally compu terize and analyse data, and to provide broad guidelines to the project directors in the task of conducting the study in their respective states. The responsibility of the project directors was to collect relevant data from secondary sources for the ^irpDse of preparing state level profiles, to work .out specific sampling plans for their state, to translate the data-collection instrument into the regional language, to collect and code data, and finally to prepare research reports. -

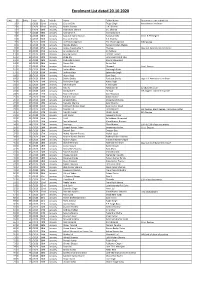

Enrolment List Dated 20.10.2020

Enrolment List dated 20.10.2020 S.No. D/ EnNo Year Date Month Name Father Name Documents to be submitted 1 D/ 1 /2020 02nd January, Gaurav Dixit Tejpal Singh Attendance Certificate 2 D/ 2 /2020 02nd January, Mohit Sharma U.K. Sharma 3 D/ 3 /2020 06th January, Shailendra Sharma S.C. Sharma 4 D/ 4 /2020 06th January, Kasiraman K. Kannuchamy K. 5 D/ 5 /2020 06th January, Saurabh Kumar Suman Ramakant Jha Grad. & PG Degree 6 D/ 6 /2020 06th January, Gaurav Sharma K.K. Sharma 7 D/ 7 /2020 06th January, Jai Prakash Agrawal Tek Chand Agrawal FIR Pending 8 D/ 8 /2020 07th January, Renuka Madan Balram Krishan Madan 9 D/ 9 /2020 07th January, Arokia Arputha Raj T. Thomas Org. LLB. Attendance Certificate 10 D/ 10 /2020 07th January, Anandakumar P. O. Paldurai 11 D/ 11 /2020 08th January, Anurag Kumar Late B.L. Grover 12 D/ 12 /2020 08th January, Atika Alvi Late Umar Mohd. Alvi 13 D/ 13 /2020 08th January, Shahrukh Kirmani Shariq Mahmood 14 D/ 14 /2020 08th January, Shreya Bali Sanjay Bali 15 D/ 15 /2020 09th January, Ashok Kumar Dhanpal Grad. Degree 16 D/ 16 /2020 09th January, Sachin Bhati Mansingh Bhati 17 D/ 17 /2020 09th January, Jaskiran Kaur Satwinder Singh 18 D/ 18 /2020 09th January, Hitain Bajaj Sunil Bajaj 19 D/ 19 /2020 09th January, Shikha Shukla Ravitosh Shukla Org. LLB. Attendace Certificate 20 D/ 20 /2020 10th Janaury, Paramjeet Singh Avtar Singh 21 D/ 21 /2020 10th Janaury, Kalimuthu M. K. Murugan 22 D/ 22 /2020 13th January, Raju N.