Cumulative Extremism: a Misguided Narrative?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018 THE TRAVELERS American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq BY Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Cliford Program on Extremism February 2018 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2018 by Program on Extremism Program on Extremism 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 www.extremism.gwu.edu Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................v A Note from the Director .........................................................................................vii Foreword ......................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary .......................................................................................................1 Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers ..........................................................5 Foreign Fighters and Travelers to Transnational Conflicts: Incentives, Motivations, and Destinations ............................................................. 5 American Jihadist Travelers: 1980-2011 ..................................................................... 6 How Do American Jihadist -

The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—And Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 6 3-20-2017 The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ramakrishna, Kumar (2017) "The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol29/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New England Journal of Public Policy The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore This article examines the radicalization of young Southeast Asians into the violent extremism that characterizes the notorious Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). After situating ISIS within its wider and older Al Qaeda Islamist ideological milieu, the article sketches out the historical landscape of violent Islamist extremism in Southeast Asia. There it focuses on the Al Qaeda-affiliated, Indonesian-based but transnational Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) network, revealing how the emergence of ISIS has impacted JI’s evolutionary trajectory. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

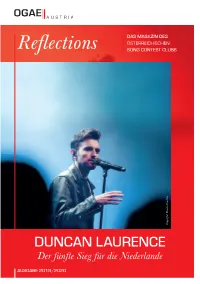

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

The UK's Experience in Counter-Radicalization

APRIL 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 5 The UK’s Experience in published in October 2005, denied having “neo-con” links and supporting that Salafist ideologies played any role government anti-terrorism policies.4 Counter-Radicalization in the July 7 bombings and blamed Rafiq admitted that he was unprepared British foreign policy, the Israeli- for the hostility—or effectiveness—of By James Brandon Palestinian conflict and “Islamophobia” these Islamist attacks: for the attacks.1 They recommended in late april, a new British Muslim that the government tackle Islamic The Islamists are highly-organized, group called the Quilliam Foundation, extremism by altering foreign policy motivated and well-funded. The th named after Abdullah Quilliam, a 19 and increasing the teaching of Islam in relationships they’ve made with century British convert to Islam, will be schools. Haras Rafiq, a Sufi member of people in government over the last launched with the specific aim of tackling the consultations, said of the meetings: 20 years are very strong. Anyone “Islamic extremism” in the United “It was as if they had decided what their who wants to go into this space Kingdom. Being composed entirely findings were before they had begun; needs to be thick-skinned; you of former members of Hizb al-Tahrir people were just going through the have to realize that people will lie (HT, often spelled Hizb ut-Tahrir), the motions.”2 about you; they will do anything global group that wants to re-create to discredit you. Above all, the the caliphate and which has acted as Sufi Muslim Council attacks are personal—that’s the a “conveyor belt” for several British As a direct result of witnessing the way these guys like it. -

Aktuelt DOKUMENTAR

10 Nr. 39 / 3.–9. oktober 2014 MORGENBLADET AKTUELT DOKUMENTAR 30. juni 2014, video: Han rusler i en erobret grensestasjon mellom Irak og Syria, sprenger et hus. Det er to år siden han flyttet fra Skien. Nå er han PR-mann for den «islamske staten», IS, i Irak. Han peker på grenseskiltene og sier: «Nå er det ingen grense lenger.» FOTO: LIVELEAKs/STILLBILDE FRA IS-VIDEO MORGENBLADET Nr. 39 / 3.–9. oktober 2014 11 DOKUMENTAR AKTUELT Bastians beslutning Hasj, konspirasjonsfilmer og dårlige venner. Hvordan en hiphopgutt fra Skien ble IS-kriger i Irak. Simen Sætre 12 Nr. 39 / 3.–9. oktober 2014 MORGENBLADET AKTUELT DOKUMENTAR en 29. juni i år ble det gjen- rhymes for skiensungdommen.» Bak nom nettstedet Liveleaks «Det var mye henging arrangementet sto Bastian og tre andre publisert en video der den gutter fra Gulset. De har dannet hip- 24 år gamle nordmannen hos kompiser. De skulle hopgruppen Gull-Z. De sier at det er Bastian Vasquez viste den lenge siden det sist var et slikt arrange- «islamske staten» (IS) sine være gangster.» ment i Skien. «Det er fint når ungdom Dnye erobringer. får et sted å være på lørdagskvelden, i Han ruslet i svart skyggelue og kjor- stedet for å henge rundt i gatene.» Mu- tel gjennom ruinene av en grensesta- sikken deres blander all slags hiphop, sjon mellom Irak og Syria, heiste det hadde skjedd, det var så ekstremt mye opplyses det, med tekster på norsk, en- svarte flagget, lo til kamera og poserte prating. Han tok seg alltid av pratinga. gelsk, spansk og afrikansk. -

Challenging the Harms of the 'Muslim Grooming Gangs' Narrative

RAC0010.1177/0306396819895727Race & ClassCockbain and Tufail 895727research-article2020 SAGE Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne Failing victims, fuelling hate: challenging the harms of the ‘Muslim grooming gangs’ narrative ELLA COCKBAIN and WAQAS TUFAIL Abstract: ‘Muslim grooming gangs’ have become a defining feature of media, political and public debate around child sexual exploitation in the UK. The dominant narrative that has emerged to explain a series of horrific cases is misleading, sensationalist and has in itself promoted a number of harms. This article examines how racist framings of ‘Muslim grooming gangs’ exist not only in extremist, far-right fringes but in mainstream, liberal discourses too. The involvement of supposedly feminist and liberal actors and the promotion of pseudoscientific ‘research’ have lent a veneer of legitimacy to essentialist, Ella Cockbain is an associate professor at University College London in the Department of Security and Crime Science and a visiting research fellow at Leiden University. Her research focuses on human trafficking, child sexual exploitation and labour exploitation. In seeking evidence- informed responses to complex issues, she has worked closely with organisations across the public, private and third sectors. Her book Offender and Victim Networks in Human Trafficking was published by Routledge in 2018. Waqas Tufail is a senior lecturer in Criminology at Leeds Beckett University. His research interests concern the policing, racialisation and criminalisation of marginalised and minority communities and the lived experiences of Muslim minorities. He is a board member of the International Sociological Association Research Committee on Racism, Nationalism, Indigeneity and Ethnicity, serves on the editorial board of Sociology of Race and Ethnicity and is co-editor of Media, Crime, Racism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). -

Women in Islamic State: from Caliphate to Camps

ICCT Policy Brief October 2019 DOI: 10.19165/2019.03.9 ISSN: 2468-0656 Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps Author: Gina Vale Within the territorial boundaries of the Islamic State’s (IS) ‘caliphate’, women were largely confined to the domestic sphere. Their roles centred on support to militant husbands and the ideological upbringing of children. The physical collapse of IS’ proto-state marks a significant turning point in women’s commitment and activism for the group. Many IS-affiliated women are now indefinitely detained within Kurdish-run camps in North-eastern Syria. The harsh living conditions therein have fostered ideological divides. While some show signs of disillusionment with IS’ ‘caliphate’ dream, others have sought to re-impose its strictures. This paper contributes to the understanding of women’s roles across the lifespan of the Islamic State, and the efficacy of independent female activism to facilitate the group’s physical recovery. It argues that IS’ post-territorial phase has brought greater autonomy and ideological authority to individual hard-line detainees. However, beyond the camps, women’s influence and ability to realise IS’ physical resurgence remains practically limited and dependent on male leadership. Keywords: Islamic State, al-Hol, Women, Gender, Propaganda, Children, Indoctrination Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps Introduction The loss of Baghouz in March 2019 marked the long-awaited territorial collapse of Islamic State’s (IS, or ISIS) ‘caliphate’.1 As a result, Kurdish forces in Syria captured thousands of its remaining fighters and supporters, with many occupying camps such as al-Hol.2 Though once effective to initially detain and process IS-affiliated persons, the population of such camps now far exceeds maximum capacity. -

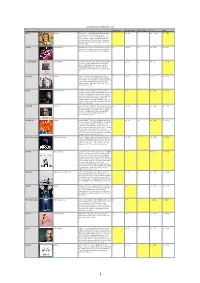

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Tele and Jury Incl Comments

Eurovision Song Contest 2019 Final My Placing Me guessing Final result Tele Jury Malta Michela Chameleon - I seriously think Malta is worth 8 11-15 16 22 - 20p 10 - 75p more this year. The recorded version of ”Chameleon” is a piece of brilliant pop but also honestly… They failed to bring it from recorded to live. The act looked a bit messy, but only 20 points from the tele voting? No that’s not fair. Albania Jonida Maliqi Ktheju tokes - I don´t have much to say here 18 16-20 18 17 - 47p 18 - 43p cause this is a kind of genre you only hear in the Eurovision and the result was expected. Czech Republic Lake Malawi Friend of a friend - This is one of the big WTF 20 21-26 11 24 - 7p 6 - 150p ´s on the night… What with the jury? 6th place really? What did the jury see in this entry? Will be fun to see how the diferent countries really voted in the breakdown later on. Germany S!sters Sister - I moved Germany from the last 6 17 21-26 24 26 - 0p 21 - 32p places up to 17 on the night cause the girls performed it well but the result was expected. I am actually surprised they got 32 points from the juries. But again one of the ”Big 5” failed a good result. Russia Sergey Lazarev Scream - A small surprise since I guessed 7 6-10 3 4 - 244p 9 - 125p Sergey would have been rewarded more in the tele votes than with the political jury voting. -

Jihadis Without Jihad? Central Eastern Europeans and Their Lack of Pathways to Global Jihad

(FEW) JIHADIS WITHOUT JIHAD? CENTRAL EASTERN EUROPEANS AND THEIR LACK OF PATHWAYS TO GLOBAL JIHAD National Security Programme POLAND Warsaw Prague CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA Bratislava Budapest HUNGARY SYRIA Damascus Baghdad IRAQ www.globsec.org AUTHORS Kacper Rekawek, Head of National Security Programme, GLOBSEC Viktor Szucs, Junior Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Martina Babikova, Junior Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Enya Hamel, GLOBSEC (FEW) JIHADIS WITHOUT JIHAD? CENTRAL EASTERN EUROPEANS AND THEIR LACK OF PATHWAYS TO GLOBAL JIHAD (3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 Bottom line up front 6 (Lack of) pathways to radical and extremist islamist jihad in Czech Republic & Slovakia 8 Introduction 8 Case studies 9 (Lack of) pathways to radical and extremist islamist jihad in Hungary 11 Introduction 11 Case studies 12 A transit country? 13 (Lack of) pathways to radical and extremist islamist jihad in Poland 15 Introduction 15 Case studies 15 Conclusions and Recommendations 17 Endnotes 20 4) (FEW) JIHADIS WITHOUT JIHAD? CENTRAL EASTERN EUROPEANS AND THEIR LACK OF PATHWAYS TO GLOBAL JIHAD INTRODUCTION For the last two years, GLOBSEC has been studying The first report was followed by a more detailed the crime-terror nexus in Europe.1 Its research team study of 56 jihadists from 5 European countries. has built up a dataset of 326 individuals arrested Their cases vividly demonstrate the practical ins for terrorism offences, expelled for alleged terrorist and outs of how a pathway towards jihad looks connections, or who died while staging terrorist like in the current European settings,3 or, to put it attacks in Europe in 2015, the peak year of European differently, what does becoming a jihadi entail and jihadism. -

Sticonpoint June 2019 Edition

June 2019 Issue I am from the Everyone knows me by Maldives. I am International Students my nickname “Willy”. I studying Aeronautics am from Myawaddy, I am a seminarian Kayine, Myanmar. I am in this institution. I staying at Camillian like to swim and dive. 20 years old. I graduated Social Center from Sappawithakhom It’s a passion of mine Prachinburi. Right to explore the School. Before my now, I am studying graduation, I didn’t have underwater beauty. English courses with any idea where to study What I like most about the Business English and what major to take up. One day, Ajarn the college is the hospitality given to me students. I think this Korn Sinchai from STIC Marketing/ by each and everyone on the campus. It institution is good Guidance and Counseling Team introduced is grateful to have a friendly for learning English. St. Theresa International College to grade 12 environment with great personalities. There are many good teachers here and students in our school including myself. Mohamed Shamaail, the environment is a good place to stay. During his presentation, I realized that this is Aeronautics Y1 Nguyen Dinh Minh Quang, what I really want for my tertiary education. Business English Y1 Moreover, the college fees are not expensive My friends call me and I would have the chance to study with Rose. I am 18 years People call me Toby. I real professors. Then, I made the decision to old. I am a Filipino am a German citizen be here at STIC. but was born here in but I grew up in Aung Thu Rain Oo, Aeronautics Y1 Thailand. -

Kuwaittimes 14-5-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RAMADAN 9, 1440 AH TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2019 28 Pages Max 43º Min 25º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17832 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Assembly set to debate New Delhi hit by rare Liverpool seeking perfection 3 grilling against premier 24 ‘air pollution’ alert 27 in bid to dethrone Man City IMSAK 03:18 Fajr 03:28 Dhur 11:44 Asr 15:20 Magrib 18:32 Isha 19:59 Saudi tankers hit by ‘sabotage attacks’ as Gulf tensions soar Kuwait condemns the ‘criminal attack’ • UAE launches probe • Iran calls incident ‘worrisome’ DUBAI: Saudi Arabia said yesterday that two of its oil tankers were among those attacked off the coast of the United Arab Emirates and said it was an attempt to under- mine the security of crude supplies amid tensions between the United States and Iran. The UAE said on Sunday that four commercial vessels were sabotaged near Fujairah emirate, one of the world’s largest bunkering hubs lying just outside the Strait of Hormuz. It did not describe the nature of the attack or say who was behind it. The UAE had not given the nationalities or other details about the ownership of the four vessels. Riyadh has identi- fied two of them as Saudi and a Norwegian company said it owned another. Details of the fourth ship were not immediately clear. Thome Ship Management said its Norwegian-registered oil products tanker MT Andrew Victory was “struck by an unknown object”. Footage seen by Reuters showed a hole in the hull at the waterline with the metal torn open inwards.