3D Digital Imaging for Knowledge Dissemination of Greek Archaic Statuary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartina-Guida-Stradario-Catania.Pdf

ITINERARI DI CATANIA CITTÀ D’ARTE ITINERARI ome scoprire a fondo le innumerevoli bellezze architettoniche, Cstoriche, culturali e naturalistiche di Catania? Basta prendere par- te agliItinerari di Catania Città d’Arte , nove escursioni offerte gra- tuitamente dall’Azienda Provinciale Turismo, svolte con l’assistenza ittà d’arte di esperte guide turistiche multilingue. Come in una macchina del tempo attraverserete secoli di storia, dalle origini greche e romane fino ai giorni nostri, passando per la rinasci- ta barocca del XVII secolo e non dimenticando Vincenzo Bellini, forse il più illustre dei suoi figli, autore di immortali melodie che hanno reso OMAGGIO! - FREE! la nostra città grande nel mondo. Catania, dichiarataPatrimonio dell’Umanità dall’Unesco per il suo Barocco, è stata distrutta dalla lava sette volte e altrettante volte riedifica- ta grazie all’incrollabile volontà dei suoi abitanti, gente animata da una grande devozione per Sant’Agata, patrona della città, cui sono dedicate tante chiese ed opere d’arte, nonché una delle più belle feste religiose AZIENDA PROVINCIALE TURISMO che si possa ammirare. PROVINCIAL TOURISM BOARD Con l’escursione al Museo di Zoologia, all’Orto Botanico e all’Erbario via Cimarosa, 10 - 95124 Catania del Mediterraneo scoprirete le peculiarità naturalistiche del territorio tel. 095 7306211 - fax: 095 316407 etneo e non solo, mentre grazie all’itinerario “Luci sul Barocco” potrete www.apt.catania.it - [email protected] effettuare una piacevole passeggiata notturna per le animate strade della movida catanese, attraversando piazze e monumenti messi in risalto da ammalianti giochi di luce. Da non perdere infine l’itinerario “Letteratura e Cinema”, un affascinan- te viaggio tra le bellezze architettoniche e le indimenticabili atmosfere protagoniste indiscusse di tanti romanzi e film di successo. -

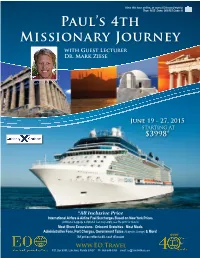

PJ15 X 061915 Layout 1

View this tour online, at www.EO.travel/mytrip Tour: PJ15 Date: 061915 Code: X Paul’s 4th Missionary Journey with Guest Lecturer Dr. Mark Ziese June 19 - 27, 2015 STARTING AT $3998* *All Inclusive Price International Airfare & Airline Fuel Surcharges Based on New York Prices (Additional baggage & Optional fees may apply, see fine print for details) Most Shore Excursions . Onboard Gratuities . Most Meals Administrative Fees, Port Charges, Government Taxes (Subject to Change) & More! *All prices reflect a 4% cash discount over www.EO.Travel P.O. Box 6098, Lakeland, Florida 33807 Ph: 863-648-0383 email: [email protected] Paul’s 4th Missionary Journey June 19, 2015 – Depart USA Your journey begins as you depart the USA. June 23, 2015 – At Sea June 20, 2015 – Arrive in Istanbul, Turkey June 24, 2015 – Valletta, Malta Arrive in Istanbul and embark on the luxurious Paul was shipwrecked on Malta around 60 AD (Acts Celebrity Equinox. 9). After the Knights of St. John successfully defended Malta against a massive Ottoman siege in 1565, they June 21, 2015 – Mykonos, Greece (On Own) built the fortified town of Valletta, naming it after their Have a delightful day exploring the exceptional beauty leader. Explore the Barrakka Gardens which were and culture of the Greek island of Mykonos with its built on a bastion of the city and offer a breathtaking lovely bays and beaches, distinctive whitewashed view of the Grand Harbor. Be sure to visit St. John’s structures and cobblestone streets. Co-Cathedral to view Caravaggio’s masterpiece, “The Beheading of John the Baptist,” the only work the June 22, 2015 – Athens & Corinth, Greece painter ever signed. -

REGI Mission to Sicily, September 2015

Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Directorate for Structural and Cohesion Policies PROGRAMME EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT COMMITTEE ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT Delegation to Sicily, Italy 23 – 25 September 2015 Wednesday, 23 September 2015 Individual arrival of the Members and the Staff to Catania–Fontanarossa Airport 14:30 first transfer to hotel (flights arriving at around 14:00) 16:30 second transfer to hotel (flight arrivings at around 16:00) For both transfer the participants of the delegation meet at the Meeting Point of Catania– Fontanarossa Airport (flight arrivals) check in at the hotel: Mercure Catania Excelsior 39 Piazza Giovanni Verga 95129 Catania +39 095 74 76 111 http://www.excelsiorcatania.com/ 18:30 – 18:45 The delegation meets in the hotel lobby 18:45 – 19:00 Bus transfer to Municipality of Catania Venue: Palazzo degli Elefanti Piazza Duomo 3, Catania 19:00 – 20:15 Meeting with Mr Enzo Bianco, the Mayor of Catania1 at Palazzo degli Elefanti, sala Giunta 20:15 – 20:30 bus transfer to dinner location (Castello Ursino) 20:30 – 22:00 Dinner hosted by Mr Enzo Bianco, the Mayor of Catania with participation of local authorities. Venue: Castello Ursino Piazza Federico II di Svevia, 3, Catania 23:30 Return by bus to hotel Mercure Catania Excelsior 1 For this event, translation only available in English and Italian Thursday, 24 September 2015 8:30 – 09:00 The delegation meets in the hotel lobby and checks out 09:00 – 09:30 Bus transfer to the Science and Technology Park of Sicily (STPS) Venue: Z.I. Blocco Palma I Stradale V. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Grand Tour of Italy the Essentials Tailor Make Your Holiday What's

Grand Tour of Italy From £2,149 per person // 21 days This epic exploration of Italy's finest cities and most beautiful countryside takes you from Venice down to Sicily and back. En route, visit the elegant cities of Rome and Florence, relax on the Amalfi Coast and cruise on Lake Como. The Essentials What's included Nine fantastic destinations in 21 days Standard Class rail travel with seat reservations The cultural capitals of Venice, Rome and Florence 20 nights’ handpicked hotel accommodation with breakfast combined with Lake Como and the destinations of the City maps and comprehensive directions to your hotels Amalfi Coast and Catania in Sicily Clearly-presented wallets for your rail tickets, hotel Return rail travel to Italy via Munich on the way out and vouchers and other documentation Zurich on the return All credit card surcharges and complimentary delivery of your travel documents Tailor make your holiday Decide when you would like to travel Adapt the route to suit your plans Upgrade your hotels Add extra nights, destinations and/or tours - Suggested Itinerary - Day 1 - London To Munich Leave London St Pancras late morning and take the Eurostar to Brussels Midi. Here, connect onto a service to Munich, via Frankfurt. You will arrive in the late evening so you might like to stock up on food for the second leg of the journey in Frankfurt, or enjoy dinner in the restaurant car on the train. Upon arrival, check into the Courtyard by Marriott City Centre (or similar) for an overnight stay. Day 2 - Munich To Venice Via The Brenner Pass Take one of Europe’s most scenic journeys as you cross the Alps through Austria’s Tyrol region and into Italy over the famous Brenner Pass. -

The Medieval Kingdom of Sicily Image Database 1

Archeologia e Calcolatori Supplemento 10, 2018, 000-000 THE MEDIEVAL KINGDOM OF SICILY IMAGE DATABASE 1. Project Overview: The Significance of the Database and the Historical Material it Covers We now experience buildings of the medieval past through the filter of repairs, restoration, and reconstruction. This may be particularly true for the monuments of the historic Kingdom of Sicily, which have been subjected to damage from earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and the aerial bombardments of World War II. In addition, South Italian monuments, like those everywhere in Italy, were usually once covered by Baroque decoration in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, much of which was later removed during a period of “remedievalization” after the unification of Italy. Urban growth, especial- ly after the middle of the twentieth century, has transformed the visual and symbolic role of these representational monuments, their relation to the urban and natural landscape, and their importance for the visual cultures of Europe and the Mediterranean. So what do we actually see when we look at a medieval monument? Whose “Middle Ages” are we actually experiencing? Are there ways to come closer to the appearance of a site prior to all the changes and modifications described above? The Kingdom of Sicily Image Database (Fig. 1) (http://kos.aahvs.duke. edu/), freely accessible online since October 2016, is an attempt to respond to this question by collecting visual documents (drawings, paintings, pho- tographs, prints…) that illustrate the appearance of, and changes to, the medieval monuments of South Italy (roughly 10th-15th centuries) (Bruzelius 2016; Bruzelius, Vitolo 2016; Vitolo 2017a, 20107b). -

Catania Guide Activities Activities

CATANIA GUIDE ACTIVITIES ACTIVITIES Greek Theatre of Taormina / Teatro Greco di Taormina Roman Villa of Casale / Villa Romana del Casale A F An impressive Hellenistic amphitheatre from the 3rd century B.C. is a One of many UNESCO sites on the island, this impressive Roman villa is a must-see for everyone. Plays and concerts are still performed here today. must-see. It holds the largest collection of Roman mosaics in the world. Via Teatro Greco 59, 98039 Taormina, Italy Villa Romana del Casale, 94015 Piazza Armerina, Italy GPS: N37.85221, E15.29205 GPS: N37.36467, E14.33458 Phone: Phone: +39 0942 610225 +39 0935 982111 Ursino Castle / Castello Ursino Benedictine Monastery of Catania / Monastero dei Benedettini B G Considered inconquerable during the Middle Ages, the gargantuan castle is Catania a truly wonderful sight. A must-visit. Inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List, this monastery is a must-see! Visit the church, ancient Roman house and the museum of art, too. Piazza Federico II di Svevia 1, 95121 Catania, Italy GPS: N37.49917, E15.08442 Via Crociferi 11, 95124 Catania, Italy GPS: N37.50297, E15.08542 Phone: Mount Etna / Etna C +39 957 152 207 Surely the No. 1 sight in Sicily, the majestic and awe-inspiring volcano standing 3,329 metres high is the largest active volcano in Europe. Biscari Palace / Palazzo Biscari GPS: N37.75440, E14.99590 H A gorgeous Rococo palace, the construction of which took over a hundred years. The meticulous work seemed to pay off! Via Museo Biscari 16, 95131 Catania, Italy Corvaja Palace / Palazzo Corvaja GPS: N37.50220, E15.09107 D A historical palace with an Arabian feel. -

Saint Matthews

Luis Tristán (1580/1585 - 1624) Saint Matthews Oil on canvas Measurements: 107 x 77 cm Spanish XVII century Painted about 1613 Description Apostle Saint Matthews? Saint Jude Tadeo?, Saint Matías ? or Saint Thomas ? AN APOSTLE BY LUIS TRISTÁN: RELATIONSHIP WITH EL GRECO, RIBERA, VELAZQUEZ AND THE NEW ITALIAN NATURALISTIC CURRENTS. The work we are studying represents an apostle in all his splendour and monumentality, whose iconographic identification is doubtful since the only attribute appearing is the halberd which is common to various apostles. Saint Matthews, creator of the first Gospel and Saint Jude Tadeo, also represented by El Greco with a halberd, are the most probable; San Matías is less probable due to having been martirized with an axe; and Saint Thomas, although the attribute does not correspond, since he died pierced by a lance, also could be the apostle represented due to his close relationship to the composition with the Saint Thomas of the Apostles by El Greco (El Greco Museum, Toledo) and the Saint Thomas by Velazquez (Orleans Museum). The painter certainly did not wish to centre his attention on an individualized identification of the saint, but rather on his general symbology as apostle: the halberd or lance with regard to his martyrdom as a form of death, the heavy tunic, with imposing folds, referring to his mighty task of spreading the Gospel continuously for the Church and the strong expression on his face in allusion to his tenacious character and indomitable conviction needed to accomplish his mission. The work can be attributed to the best work of Luis Tristán, and due to its quality may be considered a masterpiece carried out just on his return from his journey to Italy, in about 1613 when his spirit was still teeming excitedly with the ideas gathered in El Greco’s workshop and his contact with the modern Roman naturalistic currents shared with the young José Ribera. -

Chapter 5 Geology of the Urban Area of Catania (Eastern Sicily)

SEISMIC PREVENTION OF DAMAGE 83 Chapter 5 Geology of the urban area of Catania (Eastern Sicily) C. Monaco, S. Catalano, G. De Guidi & L. Tortorici Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Catania, Italy Abstract The geology of the Catania urban area (Eastern Sicily) is the result of three combined processes related to the Late Quaternary sea-level changes, the volcanic and tectonic processes and finally to human activity. The backbone of the urban area is represented by a flight of marine terraces carved on a sedimentary substratum. This is made up of a Lower-Middle Pleistocene succession of marly clays, up to 600 m thick, upwardly evolving to some tens of metres of coastal sands and fluvial-deltaic conglomerates, referred to as the Middle Pleistocene. The unconformably overlying terraced deposits, of both coastal alluvial and marine origin, are characterized by several metres of thick sands, conglomerates and silty clays. They rest on abrasion platforms distributed at different elevations dating to the sea level high-stands between 200 and 40 kyr. These indicate a strong uplift of the area which can be explained as the effect of the deformation at the footwall of the NNW-SSE trending active normal fault system located at the south-eastern lower slope of Mt. Etna that extends offshore into the Ionian sea. The sedimentary substratum is dissected by deeply entrenched valleys filled with thick lava flows, which represent most of the rocks cropping out in the city. These consist of basaltic lavas which, flowing from NW to SE, invaded the urban area in pre-historical and historical times (e.g. -

IL CASTELLO URSINO E I MUSEI DI CATANIA NEL XX SECOLO Di Alvise Spadaro

(Pubblicato su “Ricerche” a. X n. 1 Gennaio-Luglio 2006 pp. 49-102) IL CASTELLO URSINO E I MUSEI DI CATANIA NEL XX SECOLO di Alvise Spadaro alla memoria di Mario Sipala e Corrado Dollo Per l’inaugurazione del più antico museo catanese in attività, trofei, bandiere, tendaggi bianchi e rossi e un palco capace di 300 posti a sedere. Era il 30 luglio del 1858 e s'inaugurava l’Orto botanico dell’Università voluto da Tornabene Roccaforte, benedettino docente di botanica dell’Università di Catania e ampliato due anni dopo con un’area destinata alla coltivazione delle specie spontanee, grazie ad una donazione del catanese Mario Coltraro. Poi la città raggiunse così rapidamente l’impianto che non fu possibile alcun’altra espansione. Con ingresso gratuito su via Antonino Longo, sorge su un impianto che risale al 1788, e che ha mantenuto la sua struttura ottocentesca estesa per una superficie di circa mq 16.000. non suscettibili d'ampliamento. L’edificio porticato in stile neoclassico opera dell’architetto Distefano occupa il centro dell’area. L’Orto Generale di tredici piccole serre, una delle quali contiene le piante grasse della collezione del dr Gasperini; una serra caldo-umida per la riproduzione delle palme, una cinquantina di specie, e per la coltura di piante esotiche; tre vasche circolari per la coltivazione di piante acquatiche. Vi era anche una grande serra, detta Tepidario che fu demolita in seguito ai danni subiti durante l’ultimo conflitto mondiale. L’Orto Siculo di mq. 3.000 realizzato verso il 1887, ha esemplari provenienti da tutta l’Isola e specie esotiche da lungo tempo coltivate in Sicilia. -

Virtual Anastylosis of Greek Sculpture As Museum Policy for Public Outreach and Cognitive Accessibility Filippo Stanco University of Catania

University of South Florida Scholar Commons History Faculty Publications History 1-2017 Virtual Anastylosis of Greek Sculpture as Museum Policy for Public Outreach and Cognitive Accessibility Filippo Stanco University of Catania Davide Tanasi University of South Florida, [email protected] Dario Allegra University of Catania Filippo L.M. Milotta University of Catania Gioconda Lamagna Museo Archeologico Regionale “Paolo Orsi” di Siracusa See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/hty_facpub Scholar Commons Citation Stanco, Filippo; Tanasi, Davide; Allegra, Dario; Milotta, Filippo L.M.; Lamagna, Gioconda; and Monterosso, Giuseppina, "Virtual Anastylosis of Greek Sculpture as Museum Policy for Public Outreach and Cognitive Accessibility" (2017). History Faculty Publications. 8. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/hty_facpub/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Filippo Stanco, Davide Tanasi, Dario Allegra, Filippo L.M. Milotta, Gioconda Lamagna, and Giuseppina Monterosso This article is available at Scholar Commons: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/hty_facpub/8 Virtual anastylosis of Greek sculpture as museum policy for public outreach and cognitive accessibility Filippo Stanco Davide Tanasi Dario Allegra Filippo Luigi Maria Milotta Gioconda Lamagna Giuseppina Monterosso Filippo Stanco, Davide Tanasi, Dario Allegra, Filippo Luigi Maria Milotta, Gioconda Lamagna, Giuseppina Monterosso, “Virtual anastylosis of Greek sculpture as museum policy for public outreach and cognitive accessibility,” J. Electron. Imaging 26(1), 011025 (2017), doi: 10.1117/1.JEI.26.1.011025. -

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 1, Winter 2018

ITALIAN ART SOCIETY NEWSLETTER XXIX, 1, Winter 2018 An Affiliated Society of: College Art Association Society of Architectural Historians International Congress on Medieval Studies Renaissance Society of America Sixteenth Century Society & Conference American Association of Italian Studies President’s Message from Sean Roberts Scholars Committee member Tenley Bick, exploring the theme of “Processi italiani: Examining Process in Postwar March 21, 2017 Italian Art, 1945-1980.” The session was well-attended, inspired lively discussion between the audience and Dear Members of the Italian Art Society: speakers, and marks our continued successful expansion into the fields of modern and contemporary Italian Art. Dario As I get ready to make the long flight to New Donetti received a Conference Travel Grant for Emerging Orleans for RSA, I write to bring you up to date on our Scholars to present his paper “Inventing the New St. Peter’s: recent events, programs, and awards and to remind you Drawing and Emulation in Renaissance Architecture.” The about some upcoming dates for the remainder of this conference also provided an opportunity for another in our academic year and summer. My thanks are due, as series of Emerging Scholars Committee workshops, always, to each of our members for their support of the organized by Kelli Wood and Tenley Bick. IAS and especially to all those who so generously serve CAA also provided the venue for our annual the organization as committee members and board Members Business Meeting. Minutes will be available at the members. IAS website shortly, but among the topics discussed were Since the publication of our last Newsletter, our the ongoing need for more affiliate society sponsored members have participated in sponsored sessions at sessions at CAA, the pros and cons of our current system of several major conferences, our 2018 elections have taken voting on composed slates of candidates selected by the place, and several of our most important grants have Nominating Committee, the increasingly low attendance of been awarded.