The Medieval Kingdom of Sicily Image Database 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cartina-Guida-Stradario-Catania.Pdf

ITINERARI DI CATANIA CITTÀ D’ARTE ITINERARI ome scoprire a fondo le innumerevoli bellezze architettoniche, Cstoriche, culturali e naturalistiche di Catania? Basta prendere par- te agliItinerari di Catania Città d’Arte , nove escursioni offerte gra- tuitamente dall’Azienda Provinciale Turismo, svolte con l’assistenza ittà d’arte di esperte guide turistiche multilingue. Come in una macchina del tempo attraverserete secoli di storia, dalle origini greche e romane fino ai giorni nostri, passando per la rinasci- ta barocca del XVII secolo e non dimenticando Vincenzo Bellini, forse il più illustre dei suoi figli, autore di immortali melodie che hanno reso OMAGGIO! - FREE! la nostra città grande nel mondo. Catania, dichiarataPatrimonio dell’Umanità dall’Unesco per il suo Barocco, è stata distrutta dalla lava sette volte e altrettante volte riedifica- ta grazie all’incrollabile volontà dei suoi abitanti, gente animata da una grande devozione per Sant’Agata, patrona della città, cui sono dedicate tante chiese ed opere d’arte, nonché una delle più belle feste religiose AZIENDA PROVINCIALE TURISMO che si possa ammirare. PROVINCIAL TOURISM BOARD Con l’escursione al Museo di Zoologia, all’Orto Botanico e all’Erbario via Cimarosa, 10 - 95124 Catania del Mediterraneo scoprirete le peculiarità naturalistiche del territorio tel. 095 7306211 - fax: 095 316407 etneo e non solo, mentre grazie all’itinerario “Luci sul Barocco” potrete www.apt.catania.it - [email protected] effettuare una piacevole passeggiata notturna per le animate strade della movida catanese, attraversando piazze e monumenti messi in risalto da ammalianti giochi di luce. Da non perdere infine l’itinerario “Letteratura e Cinema”, un affascinan- te viaggio tra le bellezze architettoniche e le indimenticabili atmosfere protagoniste indiscusse di tanti romanzi e film di successo. -

Photo Ragusa

foto Municipalities (link 3) Modica Modica [ˈmɔːdika] (Sicilian: Muòrica, Greek: Μότουκα, Motouka, Latin: Mutyca or Motyca) is a city and comune of 54.456 inhabitants in the Province of Ragusa, Sicily, southern Italy. The city is situated in the Hyblaean Mountains. Modica has neolithic origins and it represents the historical capital of the area which today almost corresponds to the Province of Ragusa. Until the 19th century it was the capital of a County that exercised such a wide political, economical and cultural influence to be counted among the most powerful feuds of the Mezzogiorno. Rebuilt following the devastating earthquake of 1693, its architecture has been recognised as providing outstanding testimony to the exuberant genius and final flowering of Baroque art in Europe and, along with other towns in the Val di Noto, is part of UNESCO Heritage Sites in Italy. Saint George’s Church in Modica Historical chocolate’s art in Modica The Cioccolato di Modica ("Chocolate of Modica", also known as cioccolata modicana) is an Italian P.G.I. specialty chocolate,[1] typical of the municipality of Modica in Sicily, characterized by an ancient and original recipe using manual grinding (rather than conching) which gives the chocolate a peculiar grainy texture and aromatic flavor.[2][3][4] The specialty, inspired by the Aztec original recipe for Xocolatl, was introduced in the County of Modica by the Spaniards, during their domination in southern Italy.[5][6] Since 2009 a festival named "Chocobarocco" is held every year in the city. Late Baroque Towns of the Val di Noto (South-Eastern Sicily) The eight towns in south-eastern Sicily: Caltagirone, Militello Val di Catania, Catania, Modica, Noto, Palazzolo, Ragusa and Scicli, were all rebuilt after 1693 on or beside towns existing at the time of the earthquake which took place in that year. -

Download AAMD Testimony to CPAC on Request for Extension of MOU

Statement of the Association of Art Museum Directors Concerning the Proposed Extension of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Italy Concerning the Imposition of Import Restrictions on Categories of Archaeological Material Representing the Pre-Classical, Classical, and Imperial Roman Periods of Italy, as Amended Meeting of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee April 8, 2015 I. Introduction This statement is made on behalf of the Association of Art Museum Directors (the “AAMD”) regarding the proposed renewal of the Agreement Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of the Republic of Italy, last amended and extended on January 11, 2011 (the “MOU”). II. General Background American art museums generally have experienced a history of cooperation both with Italian museums and the Italian Cultural Ministry built on mutual assistance and shared interests in their respective arts and cultural heritage. American art museums have been generous in sharing works from their collections with their Italian counterparts and have also worked extensively across a wide range of activities to assist Italians in protecting their cultural heritage. In fact, for many of the large and mid-sized collecting museums, the number of works of art traveling to Italian museums exceeds the reverse. An integral part of the cultural exchanges between American museums and Italian museums are loans of works of art. In these exchanges, usually the American -

PJ15 X 061915 Layout 1

View this tour online, at www.EO.travel/mytrip Tour: PJ15 Date: 061915 Code: X Paul’s 4th Missionary Journey with Guest Lecturer Dr. Mark Ziese June 19 - 27, 2015 STARTING AT $3998* *All Inclusive Price International Airfare & Airline Fuel Surcharges Based on New York Prices (Additional baggage & Optional fees may apply, see fine print for details) Most Shore Excursions . Onboard Gratuities . Most Meals Administrative Fees, Port Charges, Government Taxes (Subject to Change) & More! *All prices reflect a 4% cash discount over www.EO.Travel P.O. Box 6098, Lakeland, Florida 33807 Ph: 863-648-0383 email: [email protected] Paul’s 4th Missionary Journey June 19, 2015 – Depart USA Your journey begins as you depart the USA. June 23, 2015 – At Sea June 20, 2015 – Arrive in Istanbul, Turkey June 24, 2015 – Valletta, Malta Arrive in Istanbul and embark on the luxurious Paul was shipwrecked on Malta around 60 AD (Acts Celebrity Equinox. 9). After the Knights of St. John successfully defended Malta against a massive Ottoman siege in 1565, they June 21, 2015 – Mykonos, Greece (On Own) built the fortified town of Valletta, naming it after their Have a delightful day exploring the exceptional beauty leader. Explore the Barrakka Gardens which were and culture of the Greek island of Mykonos with its built on a bastion of the city and offer a breathtaking lovely bays and beaches, distinctive whitewashed view of the Grand Harbor. Be sure to visit St. John’s structures and cobblestone streets. Co-Cathedral to view Caravaggio’s masterpiece, “The Beheading of John the Baptist,” the only work the June 22, 2015 – Athens & Corinth, Greece painter ever signed. -

REGI Mission to Sicily, September 2015

Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Directorate for Structural and Cohesion Policies PROGRAMME EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT COMMITTEE ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT Delegation to Sicily, Italy 23 – 25 September 2015 Wednesday, 23 September 2015 Individual arrival of the Members and the Staff to Catania–Fontanarossa Airport 14:30 first transfer to hotel (flights arriving at around 14:00) 16:30 second transfer to hotel (flight arrivings at around 16:00) For both transfer the participants of the delegation meet at the Meeting Point of Catania– Fontanarossa Airport (flight arrivals) check in at the hotel: Mercure Catania Excelsior 39 Piazza Giovanni Verga 95129 Catania +39 095 74 76 111 http://www.excelsiorcatania.com/ 18:30 – 18:45 The delegation meets in the hotel lobby 18:45 – 19:00 Bus transfer to Municipality of Catania Venue: Palazzo degli Elefanti Piazza Duomo 3, Catania 19:00 – 20:15 Meeting with Mr Enzo Bianco, the Mayor of Catania1 at Palazzo degli Elefanti, sala Giunta 20:15 – 20:30 bus transfer to dinner location (Castello Ursino) 20:30 – 22:00 Dinner hosted by Mr Enzo Bianco, the Mayor of Catania with participation of local authorities. Venue: Castello Ursino Piazza Federico II di Svevia, 3, Catania 23:30 Return by bus to hotel Mercure Catania Excelsior 1 For this event, translation only available in English and Italian Thursday, 24 September 2015 8:30 – 09:00 The delegation meets in the hotel lobby and checks out 09:00 – 09:30 Bus transfer to the Science and Technology Park of Sicily (STPS) Venue: Z.I. Blocco Palma I Stradale V. -

SICILY: CROSSROADS of MEDITERRANEAN CIVILIZATIONS Including Malta Aboard the 48-Guest Yacht Elysium May 13 – 23, 2022

JOURNEYS Beyond the ordinary SICILY: CROSSROADS OF MEDITERRANEAN CIVILIZATIONS Including Malta Aboard the 48-Guest Yacht Elysium May 13 – 23, 2022 Temple of Segesta SCHEDULE OUTLINE ITALY May 13 Depart the US Ionian May 14 Arrive in Palermo. Transfer to the Grand Hotel et des Palmes. Sea May 15 Morning tour of Palermo. Afternoon excursion to Monreale. Elysium May 16 Morning excursion to Cefalu. Board the in the afternoon and sail. May 17 Marsala. Excursion to Segesta and the hill village of Erice. May 18 Porto Empedocle. Excursion to Agrigento and Piazza Armerina. May 19 Pozzallo. Explore the Baroque towns of Modica, Palazzolo Acreide, Noto, and Ispica. May 20 Valletta, Malta. Tour Valletta and Malta’s prehistoric monuments. May 21 Syracuse. Visit the city’s ancient monuments. Motor route May 22 Giardini Naxos. Excursion to Taormina. Ship route Mediterranean Air route Sea May 23 Palermo. Disembark and transfer to the airport. PROGRAM NARRATIVE Many places in the Mediterranean can lay claim to being a “crossroads of cultures and civilizations,” but none with better justification than Sicily. For, 3,000 years, wave after wave of new cultures, ideas and artistic techniques have swept over the island, leaving in their wake temples, theaters, castles villages, and extraordinary works of art that together have earned Sicily the reputation of an “open-air museum.” Our itinerary demonstrates the importance of Sicily to Greek civilization in the great theaters at Syracuse and Taormina and in the Doric temples at Agrigento and Segesta. Roman remains mingle with the Greek in Syracuse, and the wealth of Imperial Rome is evident in the 3rd-century villa near Piazza Armerina. -

TAR Lazio – Roma – Sezione I – Ricorso R.G. N. 7714/2017 Notificazione Per Pubblici Proclami – Ordinanza N

Avv. Donatella SPINELLI Avvocatura Comunale TORINO VIA CORTE D’APPELLO 16 TEL. 011.01131155 FAX 011.011.31119 [email protected] TAR Lazio – Roma – sezione I – Ricorso R.G. n. 7714/2017 Notificazione per pubblici proclami – Ordinanza n. 83862018 * * * Il Comune di Torino, con il ricorso in epigrafe, proposto contro la Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri e il Ministero dell’Economia, nonché, per quanto occorrer possa, contro la Conferenza Unificata di cui all’art. 8 del decreto legislativo 28 agosto 1997, n. 281 e notificato, ad ogni buon fine, al Comune di Bologna, ha chiesto l’annullamento in parte qua e per quanto d’interesse, previe misure cautelari, del Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri 10 marzo 2017, recante «Disposizioni per l’attuazione dell’articolo 1, comma 439, della legge 11 dicembre 2016, n. 232. (Legge di bilancio 2017)», in particolare all’art. 3, comma 4, e alla tabella D ove la stessa considera il Comune di Torino; nonché, per quanto occorrer possa, dell’intesa con la Conferenza unificata di cui all’art. 8 del decreto legislativo 28 agosto 1997, n. 281, acquisita nella seduta del 23 febbraio 2017; di ogni atto connesso, presupposto o consequenziale. I motivi di ricorso proposti sono: I. Violazione e falsa applicazione della l. n. 392/1941, del d.P.R. n. 187/1998, della l. n. 232/2016, art. 1, commi 438-439; incompetenza; eccesso di potere per sviamento, difetto d’istruttoria e manifesta irragionevolezza II. Violazione e falsa applicazione della l. n. 392/1941, del d.P.R. n. -

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS from SOUTH ITALY and SICILY in the J

ANCIENT TERRACOTTAS FROM SOUTH ITALY AND SICILY in the j. paul getty museum The free, online edition of this catalogue, available at http://www.getty.edu/publications/terracottas, includes zoomable high-resolution photography and a select number of 360° rotations; the ability to filter the catalogue by location, typology, and date; and an interactive map drawn from the Ancient World Mapping Center and linked to the Getty’s Thesaurus of Geographic Names and Pleiades. Also available are free PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads of the book; CSV and JSON downloads of the object data from the catalogue and the accompanying Guide to the Collection; and JPG and PPT downloads of the main catalogue images. © 2016 J. Paul Getty Trust This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. First edition, 2016 Last updated, December 19, 2017 https://www.github.com/gettypubs/terracottas Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu/publications Ruth Evans Lane, Benedicte Gilman, and Marina Belozerskaya, Project Editors Robin H. Ray and Mary Christian, Copy Editors Antony Shugaar, Translator Elizabeth Chapin Kahn, Production Stephanie Grimes, Digital Researcher Eric Gardner, Designer & Developer Greg Albers, Project Manager Distributed in the United States and Canada by the University of Chicago Press Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Yale University Press, London Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: J. -

Grand Tour of Italy the Essentials Tailor Make Your Holiday What's

Grand Tour of Italy From £2,149 per person // 21 days This epic exploration of Italy's finest cities and most beautiful countryside takes you from Venice down to Sicily and back. En route, visit the elegant cities of Rome and Florence, relax on the Amalfi Coast and cruise on Lake Como. The Essentials What's included Nine fantastic destinations in 21 days Standard Class rail travel with seat reservations The cultural capitals of Venice, Rome and Florence 20 nights’ handpicked hotel accommodation with breakfast combined with Lake Como and the destinations of the City maps and comprehensive directions to your hotels Amalfi Coast and Catania in Sicily Clearly-presented wallets for your rail tickets, hotel Return rail travel to Italy via Munich on the way out and vouchers and other documentation Zurich on the return All credit card surcharges and complimentary delivery of your travel documents Tailor make your holiday Decide when you would like to travel Adapt the route to suit your plans Upgrade your hotels Add extra nights, destinations and/or tours - Suggested Itinerary - Day 1 - London To Munich Leave London St Pancras late morning and take the Eurostar to Brussels Midi. Here, connect onto a service to Munich, via Frankfurt. You will arrive in the late evening so you might like to stock up on food for the second leg of the journey in Frankfurt, or enjoy dinner in the restaurant car on the train. Upon arrival, check into the Courtyard by Marriott City Centre (or similar) for an overnight stay. Day 2 - Munich To Venice Via The Brenner Pass Take one of Europe’s most scenic journeys as you cross the Alps through Austria’s Tyrol region and into Italy over the famous Brenner Pass. -

Actes Dont La Publication Est Une Condition De Leur Applicabilité)

30 . 9 . 88 Journal officiel des Communautés européennes N0 L 270/ 1 I (Actes dont la publication est une condition de leur applicabilité) RÈGLEMENT (CEE) N° 2984/88 DE LA COMMISSION du 21 septembre 1988 fixant les rendements en olives et en huile pour la campagne 1987/1988 en Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal LA COMMISSION DES COMMUNAUTÉS EUROPÉENNES, considérant que, compte tenu des donnees reçues, il y a lieu de fixer les rendements en Italie, en Espagne et au vu le traité instituant la Communauté économique euro Portugal comme indiqué en annexe I ; péenne, considérant que les mesures prévues au présent règlement sont conformes à l'avis du comité de gestion des matières vu le règlement n0 136/66/CEE du Conseil, du 22 grasses, septembre 1966, portant établissement d'une organisation commune des marchés dans le secteur des matières grasses ('), modifié en dernier lieu par le règlement (CEE) A ARRÊTÉ LE PRESENT REGLEMENT : n0 2210/88 (2), vu le règlement (CEE) n0 2261 /84 du Conseil , du 17 Article premier juillet 1984, arrêtant les règles générales relatives à l'octroi de l'aide à la production d'huile d'olive , et aux organisa 1 . En Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal, pour la tions de producteurs (3), modifié en dernier lieu par le campagne 1987/ 1988 , les rendements en olives et en règlement (CEE) n° 892/88 (4), et notamment son article huile ainsi que les zones de production y afférentes sont 19 , fixés à l'annexe I. 2 . La délimitation des zones de production fait l'objet considérant que, aux fins de l'octroi de l'aide à la produc de l'annexe II . -

Tour Factsheet

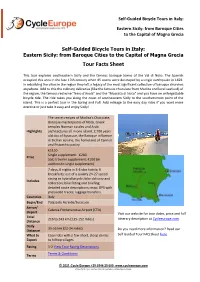

Self-Guided Bicycle Tours in Italy: Eastern Sicily: from Baroque Cities to the Capital of Magna Grecia Self-Guided Bicycle Tours in Italy: Eastern Sicily: from Baroque Cities to the Capital of Magna Grecia Tour Facts Sheet This tour explores southeastern Sicily and the famous baroque towns of the Val di Noto. The Spanish occupied this area in the late 17th century when 45 towns were destroyed by a single earthquake in 1693. In rebuilding the cities in the region they left a legacy of the most significant collection of baroque churches anywhere. Add to this the culinary delicacies (like the famous chocolate from Modica and local seafood) of the region, the famous red wine "Nero d'Avola" and the "Moscato di Noto" and you have an unforgettable bicycle ride. The ride takes you along the coast of southeastern Sicily to the southernmost point of the island. This is a perfect tour in the Spring and Fall. Add mileage to the easy day rides if you want more exercise or just take it easy and enjoy Sicily! The secret recipes of Modica's Chocolate, Baroque masterpeices of Noto, Greek temples Norman castles and Arab Highlights architectures all in one island, 2,700 years old city of Syracuse, the Baroque influence in Sicilian cuisine, the homeland of Cannoli and Pistacchio pastry €1150 Single supplement: €200 Price Solo traveler supplement: €100 (in addition to single supplement) 7 days, 6 nights in 3-4 star hotels; 6 breakfasts; use of a quality 24-27 speed racing or hybrid bicycle; bike delivery and Includes collection; bike fitting and briefing; detailed route descriptions; map; GPS with preloaded tracks; luggage transfers. -

A Small Place in Italy Free

FREE A SMALL PLACE IN ITALY PDF Eric Newby | 240 pages | 06 Jan 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007367900 | English | London, United Kingdom 20 Best Places to Visit in Italy (+ Map & Photos) | Earth Trekkers This is a list of cities and towns A Small Place in Italy Italy, ordered alphabetically by region regioni. See also city ; urban planning. List of cities and towns in Italy Article Additional Info. Article Contents. Print print Print. Table Of Contents. Facebook Twitter. Give Feedback. Let us know if you have suggestions to improve this article requires login. External Websites. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree See Article History. Abruzzi Atri. Reggio di Calabria. Vibo Valentia. Ariano Irpino. Castellammare di Stabia. Nocera Inferiore. Sessa Aurunca. Torre Annunziata. Torre del Greco. Cividale A Small Place in Italy Friuli. Castel Gandolfo. Civita Castellana. Busto Arsizio. Sesto San Giovanni. Ascoli Piceno. Civitanova Marche. Casale Monferrato. Canosa di Puglia. Ceglie Messapico. Gioia del Colle. Gravina in Puglia. Martina Franca. Ruvo di Puglia. San Giovanni Rotondo. Mazara del Vallo. Palazzolo Acreide. Piazza Armerina. Termini Imerese. Chianciano Terme. Montecatini Terme. San Gimignano. San Giuliano Terme. Bassano del Grappa. Castelfranco Veneto. Peschiera del Garda. Vittorio Veneto. Learn More in these related Britannica articles:. Cityrelatively permanent and A Small Place in Italy organized centre of population, of greater size or importance than a town or village. The name city is given to certain urban communities by virtue of some legal or conventional distinction that can vary between regions or nations.