The Secret Language Oftolkien's Dwarves Tessamram JRR Tolkien

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Exclusive on Set Page 2 Caption

Page 1 Cinema Exclusive on set Page 2 Caption: In July 2013, as Martin Freeman and Peter Jackson looked on, Sir Ian McKellen shot his last scene as Gandalf Title: The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies On December 10th the last journey to Middle-earth opens in theaters. Cinema was on set and saw devastated cities and elves smeared with blood Page 3 Cover Story “After these battles, a little drama is quite enticing” – Peter Jackson Caption: Although Bard the Bowman is only vaguely described in the book, the character plays a central role in “The Battle of the Five Armies.” Page 4 Caption: “The Tinkerbell of Middle-earth: “She is sweet, but you shouldn’t get into it with her,” Evangeline Lilly warns about her character, the Ninja-elf Tauriel By Philipp Schulze Thick snowflakes fall quietly on the crumbled city walls of Dale. Richly decorated wells and gates, now overgrown with grass and weeds, testify to the former riches of the kingdom in the north of Middle-earth. And houses, slippery paths, and a row of rotten trees give an impression of the catastrophe that must have happened here. 171 years ago, Smaug the dragon breathed fire on Dale and laid waste to the city. Now the metropolis at the foot of Erebor is once again the scene of death and destruction. Frightening Orcs have begun to hunt the men who have fled to the ruins of Dale from Esgaroth. With swords and axes drawn, they fight their way, screaming loudly, through the narrow allies of the ruined city. -

A Secret Vice: the Desire to Understand J.R.R

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 A Secret Vice: The Desire to Understand J.R.R. Tolkien’s Quenya Or, Out of the Frying-Pan Into the Fire: Creating a Realistic Language as a Basis for Fiction Cheryl Cardoza In a letter to his son Christopher in February of 1958, Tolkien said “No one believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real” (Letters 264). He added that The Lord of the Rings “was an effort to create a situation in which a common greeting would be elen síla lúmenn’ omentielmo,1 and that the phrase long antedated the book” (Letters 264-5). Tolkien often felt guilty about this, his most secret vice. Even as early as 1916, he confessed as much in a letter to Edith Bratt: “I have done some touches to my nonsense fairy language—to its improvement. I often long to work at it and don’t let myself ‘cause though I love it so, it does seem a mad hobby” (Letters 8). It wasn’t until his fans encouraged him, that Tolkien started to 1 Later, Tolkien decided that Frodo’s utterance of this phrase was in error as he had used the exclusive form of we in the word “omentielmo,” but should have used the inclusive form to include Gildor and his companions, “omentielvo.” The second edition of Fellowship reflected this correction despite some musings on leaving it to signify Frodo being treated kindly after making a grammatical error in Quenya (PE 17: 130-131). -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

ARMIES of the HOBBIT Designer’S Commentary, February 2021

ARMIES OF THE HOBBIT Designer’s Commentary, February 2021 The following commentary is intended to complement the A note on the Allies Matrix: We have had a few questions Armies of The Hobbit. It is presented as a series of questions asking us about the levels of alliance presented in the Allies and answers; the questions are based on ones that have Matrix; ‘should this army be Historical with this one?’, or been asked by players, and the answers are provided by the ‘why isn’t X Historical Allies with Y?’. rules writing team and explain how the rules are intended to be used. The commentaries help provide a default When we developed the Allies Matrix we spent a lot of time setting for your games, but players should always feel free working out timelines, deciding what timelines each Army to discuss the rules before a game, and change things as List represents, and cross referencing these to give the final they see fit if they both want to do so (changes like this are Allies Matrix. usually referred to as ‘house rules’). Historical Allies represent those that actually fought together, Our commentaries are updated regularly; when changes not just co-existed. So, for example, the reason that The are made, any changes from the previous version will be Fellowship are not Historical Allies with the Dead of highlighted in magenta. Where the stated update has a Dunharrow is simply because the Fellowship had been broken note, e.g. ‘Regional update’, this means it has had a local before the Dead were recruited by Aragorn, and so they did update, only in that language, to clarify a translation issue not fight alongside each other. -

Middle-Earth: the Wizards Characters(Hero) Resources(Hero

Middle-earth: The Wizards Card-list (484 cards) Sold in starters and boosters (no cards from other sets needed to play). A booster (15 cards, 36 boosters per display) holds 1 rare, 3 uncommons, and 11 commons. A starter holds a fixed set (at random), 3 rares, 9 uncommons, and 40 commons. R: rare; U: uncommon; CA1: once on general common sheet; CA2: twice on general common sheet; CB1: once on booster-only common sheet; CB2: twice on booster-only common sheet; F#: in # different fixed sets (out of 5). Look at the Fixed pack specs to see what cards are in in which fixed set. Characters (hero) Thorin II R Gwaihir R Risky Blow CA Thranduil F1 Halfling Stealth CB2 Roäc the Raven R Adrazar F1 Vôteli CB Halfling Strength CB2 Sacrifice of Form R Alatar F2 Vygavril R Hauberk of Bright Mail CA Sapling of the White Tree U Anborn U Wacho U Healing Herbs CA2 Scroll of Isildur U Annalena F2 Hiding R Secret Entrance R Aragorn II F1 Resources (hero) Hillmen U Secret Passage CA Arinmîr U A Chance Meeting CB Hobbits R Shadowfax R Arwen R A Friend or Three CB2 Horn of Anor CB Shield of Iron-bound Ash CA2 Balin U Align Palantir U Horses CA Skinbark R Bard Bowman F2 Anduin River CB2 Iron Hill Dwarves F1 Southrons R Barliman Butterbur U Anduril R Kindling of the Spirit CA Star-glass U Beorn F1 Army of the Dead R Knights of Dol Amroth U Stars U Beregond F1 Ash Mountains CB Lapse of Will U Stealth CA Beretar U Athelas U Leaflock U Sting U Bergil U Beautiful Gold Ring CA2 Lesser Ring U Stone of Erech R Bifur CB Beornings F1 Lordly Presence CB2 Sun U Bilbo R Bill -

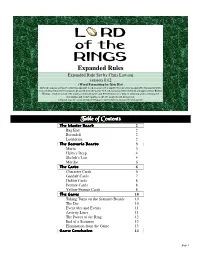

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson Version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) the Following Is a Rewrite of the Existing Rule Book

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) The following is a rewrite of the existing rule book. It is not yet complete but the sections included explain the rules in more detail than the existing set provided with the game. The following has been checked and approved by Reiner Knizia. (Author’s note: My thanks to Chris Bowyer and Reiner Knizia for help in checking and correcting the documents and to the citizens of the rec.games.board.newsgroup. Original may be found at http://freespac e.virgin.net/chris.lawson/rk/lotr/faq.htm Table of Contents The Master Board 2 Bag End 2 Rivendell 2 Lothlórien 2 The Scenario Boards 3 Moria 3 Helm’s Deep 4 Shelob’s Lair 5 Mordor 6 The Cards 6 Character Cards 6 Gandalf Cards 7 Hobbit Cards 8 Feature Cards 8 Yellow Feature Cards 8 The G am e 10 Taking Turns on the Scenario Boards 10 The Die 10 Event tiles and Events 11 Activity Lines 11 The Power of the Ring 12 End of a Scenario 13 Elimination from the Game 13 G am e Conclusion 14 Page 1 T he M aster Board The master board shows three locations (Bag End, Rivendell and Lothlórien) and four scenarios (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor). selects a card from hand and passes it to the player on the left. Bag End This continues until everyone has received and passed on one The game starts at Bag End. -

A Tolkien Magazine

The Ivy Bush A Tolkien Magazine May/June 2016 In This Issue Benita Prins Fearless Fictitious Females I. Salogel The Fifth Five Inside This Issue Pagination begins AFTER the contents page Fearless Fictitious Females.................................... Page 7 The Fifth Five........................................................ Page 2 Cast and Crew Birthdays in May and June............. Page 10 Did You Know? (book)........................................... Page 6 Did You Know? (movie)......................................... Page 9 Did You Notice?.................................................... Page 6 Elvish Word of the Month..................................... Page 5 Funny Pictures...................................................... Page 11 The Gondorian Gazette......................................... Page 11 Hobbit Fun: Beren and Lúthien Wordsearch.......... Page 5 Jokes!................................................................... Page 4 Language Corner................................................... Page 1 Quote of the Month............................................. Page 11 Short Stories: Elf Poems........................................ Page 4 Something to Think About.................................... Page 9 Test Your LOTR Knowledge!................................... Page 9 That Was Poetry!: A Middle-earth Lullaby............. Page 1 What If... …........................................................... Page 6 Would You Rather?............................................... Page 6 Please Contribute! The Ivy -

Gandalf: One Wizard to Lead Them, One to Find Them, One to Bring Them And, Despite the Darkness, Unite Them

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 Gandalf: One Wizard to lead them, one to find them, one to bring them and, despite the darkness, unite them. Alex Gunn Middle Earth is a wonderful but strangely familiar place. The Hobbits, Elves, Men and other peoples who live in caves, forests, mountain ranges and stone cities, are all combined by Tolkien to create a fantasy world which is full of wonder, beauty and magic. However, looking past these fantastical elements, we can see that Middle Earth has many similarities to the society in which we live. The different races of Middle Earth have distinct and deep differences and often keep themselves separate from one another because of mutual distrust or dislike. Due to these divisions, only one person, one who does not belong to any particular race or people, can unite them for the coming war: Gandalf the Wizard who embodies the qualities needed to be an effective leader in our world. As Sue Kim points out in her book Beyond black and White: Race and Postmodernism in Lord of the Rings, Tolkien himself declared that, “the desire to converse with other living things is one of the great allurements of fantasy” (Kim 555). Given this belief, it is no surprise that Tolkien,‘fills his imagined worlds with a plethora of intelligent non human races and exotic ethnicities, all changing over time: Elves, Dwarves, Men, Hobbits, Ents, Trolls, Orcs, Wild Men, talking beasts and embodied spirits’ (Kim 555). This plethora, as Kim puts it, makes Gandalf an important literary tool for Tolkien because to believe that such a varied mix of people, creatures, races and ethnicities live in complete harmony would feel false and perhaps too convenient. -

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien Robin Veenman BA Thesis Tilburg University 18/06/2019 Supervisor: David Janssens Second reader: Sander Bax Abstract The work of J.R.R. Tolkien appears to resemble various aspects from Norse mythology and the Norse sagas. While many have researched these resemblances, few have done so specifically on the dark side of Tolkien’s work. Since Tolkien himself was fascinated with the dark side of literature and was of the opinion that monsters served an essential role within a story, I argue that both the monsters and Tolkien’s attraction to Norse mythology and sagas are essential phenomena within his work. Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter one: Tolkien’s Fascination with Norse mythology 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Humphrey Carpenter: Tolkien’s Biographer 8 1.3 Concrete Examples From Jakobsson and Shippey 9 1.4 St. Clair: an Overview 10 1.5 Kuseela’s Theory on Gandalf 11 1.6 Chapter Overview 12 Chapter two: The monsters Compared: Midgard vs Middle-earth 14 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Dragons 15 2.3 Dwarves 19 2.4 Orcs 23 2.5 Wargs 28 2.6 Wights 30 2.7 Trolls 34 2.8 Chapter Conclusion 38 Chapter three: The Meaning of Monsters 41 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 The Dark Side of Literature 42 3.3 A Horrifically Human Fascination 43 3.4 Demonstrare: the Applicability of Monsters 49 3.5 Chapter Conclusion 53 Chapter four: The 20th Century and the Northern Warrior-Ethos in Middle-earth 55 4.1 Introduction 55 4.2 An Author of His Century 57 4.3 Norse Warrior-Ethos 60 4.4 Chapter Conclusion 63 Discussion 65 Conclusion 68 Bibliography 71 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost I have to thank the person who is evidently at the start of most thesis acknowledgements -for I could not have done this without him-: my supervisor. -

A Brief Introduction to Constructed Languages

A Brief Introduction to Constructed Languages An essay by Laurier Rochon Piet Zwart Institute : June 2011 3750 words Abstract The aim of this essay will be to provide a general overview of what is considered a "constructed language" (also called conlang, formalized language or artificial language) and explore some similarities, differences and specific properties that set these languages apart from natural languages. This essay is not meant to be an exhaustive repertoire of all existing conlangs, nor should it be used as reference material to explain or dissect them. Rather, my intent is to explore and distill meaning from particular conlangs subjectively chosen for their proximity to my personal research practice based on empirical findings I could infer from their observation and brief use. I will not tackle the task of interpreting the various qualities and discrepancies of conlangs within this short study, as it would surely consist of an endeavour of its own. It should also be noted that the varying quality of documentation available for conlangs makes it difficult to find either peer-reviewed works or independent writings on these subjects. As a quick example, many artistic languages are conceived and solely used by the author himself/herself. This person is obviously the only one able to make sense of it. This short study will not focus on artlangs, but one would understand the challenge in analyzing such a creation: straying away from the beaten path affords an interesting quality to the work, but also renders difficult a precise analytical study of it. In many ways, I have realized that people involved in constructing languages are generally engaging in a fringe activity which typically does not gather much attention - understandably so, given the supremacy of natural languages in our world. -

Med20 Character Creation Rules

MIDDLE -EARTH D20 CHARACTER CREATION RULES To create characters for this campaign, o +4 racial bonus on any Craft skill of the players will use 25 points to purchase abilities player's choice — it should be noted that according to the Purchase rules on pages 15-16 Ñoldor were legendary for their work with of the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Core precious metals and jewelry. Rulebook . Then, character creation proceeds as o +2 racial bonus on any Perform (Sing) described in the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game checks. Core Rulebook . Additionally, players will create o +2 racial bonus on saves vs. fire. a 2 nd -level character, but the 1 st -level must be a o +2 racial bonus on saves vs. poison. basic NPC class ! Players may use the Pathfinder o Immune to Aging: Ñoldor Elves are Roleplaying Game Advanced Player’s Guide , immortal unless killed. Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Ultimate Combat , o Ñoldor Elves do not sleep, meditating and Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Ultimate Magic instead for about three hours every day. to create their characters. For all sources, use o Immune to natural cold. the following rules modifications. In addition, o Immune to disease, mundane or magical. the Variant Rules for Armor as Damage o Immune to scarring. Reduction, Called Shots, Piecemeal Armor, o Movement unimpeded by snow or wooded and Wounds and Vigor from Pathfinder terrain. Roleplaying Game Ultimate Combat (pp. 191-207) o Immune to any fear effects caused by are being utilized. Please note that these rules undead. are subject to change at any time without prior o Cannot be turned into undead. -

Khuzdul Corinna Langer Sümeyra Altintas

Tolkiensprachen Khuzdul Corinna Langer Sümeyra Altintas Khuzdul Erfinder: J. R. R. Tolkien Jahr: ca. 1930 Ziel: Ästhetik, Linguistik Phonologie: sogut wie keine Informationen vorhanden Morphologie: Wurzel-Schema / wie in semitischen Sprachen Lexikon: sehr klein Allgemeines • Aule erschuf die Zwerge und ihre Sprache Khuzdul (auch Agla genannt - von „aglab“ tongue in Quenya) • geheime Sprache der Zwergen unter sich → pflegten und hüteten sie „wie einen Schatz“ vor Freund und Feind → wurde nichtmehr als Muttersprache sondern nur als überlieferte Sprache gesprochen und blieb deshalb über die Jahre hinweg sehr konstant (kein Sprachwandel) • mit anderen Völkern nutzen sie die Gemeinsprache Westron • eigene Gebärdensprache Iglishmek → im Gegensatz zu Khuzdul mehr benutzt und von Sprachwandel beeinflusst • jeder Zwerg hat zwei Namen: → einen inneren, geheimen Namen in Khuzdul (nichtmal auf Grabinschriften benutzt) → einen Namen in der Gemeinsprache Westron (z.B. Balin) • Schriftsystem: Runen (Angerthas Moria) in Stein geritzt • ein Haus der Menschen (Haus Hador) durfte es im 1. Zeitalter lernen, es war für Menschen aber sehr schwierig auszusprechen • Elben hatten kein Interesse, nur wenige durften es im 2. Zeitalter für Linguistische Zwecke lernen Linguistik • Angelehnt an semitische Sprachen (wie z.B Arabisch / Hebräisch ) • Wurzel aus Konsonanten → normalerweise aus 3 Radikalen (z.B. Kh-Z-D „dwarvish“) Tolkiensprachen Khuzdul Corinna Langer Sümeyra Altintas → bei einer Wurzel aus 2 Radikalen wird ein glottaler Verschlusslaut angefügt, der nicht als eige- nes Phonem gilt (z.B. Z-N „dark, dim“ → uzn „dimness“ [ʔuzn]) • initial sind keine zwei Konsonanten erlaubt, final allerdings schon → Silbenstruktur: (C)VC(C*) • das Einfügen von Vokalen zwischen die Radikale bildet Worte; verschiedene Vokale können nicht nur verschiedene Bedeutungen sondern auch grammatische Informationen codieren → z.B: Sg.