Unit 30 Cities in the 18 Century-1*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

IES & PSU's IES & PSU's

GENERAL STUDIES for IES & PSU’s STUDY MATERIAL 1. HISTORY 2. INDIAN-POLITY 3. ECONOMICS 4. GEOGRAPHY 5. LIFE-SCIENCE Published by: ENGINEERS INSTITUTE OF INDIA-E.I.I. ALL RIGHT RESERVED 28B/7 Jiasarai Near IIT Hauzkhas Newdelhi-110016 ph. 011-26514888. www.engineersinstitute.com 2014 By Engineers Institute of India ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems. Engineers Institute of India 28-B/7, Jia Sarai, Near IIT Hauz Khas New Delhi-110016 Tel: 011-26514888 Publication Link: www.engineersinstitute.com/publication ISBN: 978-93-5156-847-6 Price: Rs. 375.00 Published by: ENGINEERS INSTITUTE OF INDIA-E.I.I. ALL RIGHT RESERVED 28B/7 Jiasarai Near IIT Hauzkhas Newdelhi-110016 ph. 011-26514888. www.engineersinstitute.com A word to the students Knowledge of General Studies is very important to score a good marks into examinations like Engineering services -UPSC, Civil Services, State public service commissions, State engineering services, State Electricity board, SSC, Public sector undertakings & many promising and prestigious competitions. Preparation for General Studies can’t be underestimate as it is compulsory to qualify for many exams; this may contribute your score upto top ranks with final selections. You need to plan your study as per recen t examination pattern, which help you to understand the core area to focus in more details. -

History Optional PAPER

www.gradeup.co History Optional PAPER – I 1. Sources: Archaeological sources: Exploration, excavation, epigraphy, numismatics, monuments. Literary sources: Indigenous: Primary and secondary; poetry, scientific literature, literature, literature in regional languages, religious literature. Foreign accounts: Greek, Chinese and Arab writers. 2. Pre-history and Proto-history: Geographical factors; hunting and gathering (Palaeolithic and Mesolithic); Beginning of agriculture (Neolithic and chalcolithic). 3. Indus Valley Civilization: Origin, date, extent, characteristics, decline, survival and significance, art and architecture. 4. Megalithic Cultures: Distribution of pastoral and farming cultures outside the Indus, Development of community life, Settlements, Development of agriculture, Crafts, Pottery, and Iron industry. 5. Aryans and Vedic Period: Expansions of Aryans in India. 1 www.gradeup.co Vedic Period: Religious and philosophic literature; Transformation from Rig Vedic period to the later Vedic period; Political, social and economic life; Significance of the Vedic Age; Evolution of Monarchy and Varna system. 6. Period of Mahajanapadas: Formation of States (Mahajanapada): Republics and monarchies; Rise of urban centres; Trade routes; Economic growth; Introduction of coinage; Spread of Jainism and Buddhism; Rise of Magadha and Nandas. Iranian and Macedonian invasions and their impact. 7. Mauryan Empire: Foundation of the Mauryan Empire, Chandragupta, Kautilya and Arthashastra; Ashoka; Concept of Dharma; Edicts; Polity, Administration; -

Sher Shah Suri

MODULE-3 FORMATION OF MUGHAL EMPIRE TOPIC- SHER SHAH SURI PRIYANKA.E.K ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LITTLE FLOWER COLLEGE, GURUVAYOOR Sher Shah Suri, whose original name was Farid was the founder of the Suri dynasty. Son of a petty jagirdar, neglected by his father and ill treated by his step-mother, he very successfully challenged the authority of Mughal emperor Humayun, drove him out of India and occupied the throne of Delhi. All this clearly demonstrates his extra-ordinary qualities of his hand, head and heart. Once again Sher Shah established the Afghan Empire which had been taken over by Babur. The intrigues of his mother compelled the young Farid Khan to leave Sasaram (Bihar), the jagir of his father. He went to Jaunpur for studies. In his studies, he so distinguished himself that the subedar of Jaunpur was greatly impressed. He helped him to become the administrator of his father’s jagir which prospered by his efforts. His step-mother’s jealousy forced him to search for another employment and he took service under Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar, who gave him the title of Sher Khan for his bravery in killing a tiger single-handed. But the intrigues of his enemies compelled him to leave Bihar and join the camp of Babur in 1527. He rendered valuable help to Babur in the campaign against the Afghans in Bihar. In due course, Babur became suspicious of Sher Khan who soon slipped away. As his former master Bahar Khan, the ruler of South Bihar had died, he was made the guardian and regent of the minor son of the deceased. -

CENTRE of ADVANCED STUDY Session 2019-2020 Department of History A.M.U., Aligarh

CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Session 2019-2020 Department of History A.M.U., Aligarh B.A. – Ist Semester HSB-154: Ancient India (Pre-History to Indus Civilization) Teachers: Dr. O.P. Srivastav Total No. of Lectures = 40 Dr. Fazila Shahnawaz UNIT-I a) India’s physical features: a brief survey of geological formation of India. b) Pre-history and Proto-history: basis of classification. c) Early history of humans: evolution of human species. Early appearance of Anatomically Modern Man (AMM) and the Modern human in India: Archaeological evidence. d) Paleolithic Age: Three cultural phases: Lower, Middle and Upper. UNIT-II Brief Study of Pre-historic Cultures a) Mesolithic Culture: Northern and Western Zone; Central, Eastern and Southern Zone. b) The ‘Neolithic Revolution’: Meaning of ‘The Neolithic Revolution’; The earliest agricultural communities, 7000-4800 BC; Coming of Agriculture and Pastoralism. c) Significance of Mehrgarh. Neolithic Cultures of Central and Eastern India, post 3000 BC. Northern and early southern Neolithic culture after c. 3000 B.C. d) Antecedents of the Indus civilization: appearance of Bronze Age in the Indus Basin c.4000-3200 BC. UNIT-III Chalcolithic and Bronze Age in India a) Early Bronze Age Cultures, the Helmand Civilization, early Indus cultures. b) The Indus Civilization: Extent and population, Agriculture, Craft Production, Urbanization (cities and towns), Trade, Culture: writing, art and religion; polity. c) Decline of Indus/Harappan Civilization. d) Non urban Chalcolithic cultures, till 1500 BC: Chalcolithic cultures of the Border land and the Indus basin, Malwa and Deccan before 1500 BC. Language before 1500 B.C. Reading List: Agrawal, D.P. -

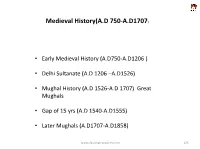

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707)

Medieval History(A.D 750-A.D1707) • Early Medieval History (A.D750-A.D1206 ) • Delhi Sultanate (A.D 1206 –A.D1526) • Mughal History (A.D 1526-A.D 1707) Great Mughals • Gap of 15 yrs (A.D 1540-A.D1555) • Later Mughals (A.D1707-A.D1858) www.classmateacademy.com 125 The years AD 750-AD 1206 • Origin if Indian feudalism • Economic origin beginning with land grants first by satavahana • Political origin it begins in Gupta period ,Samudragupta started it (samantha system) • AD750-AD950 peak of feudalism ,it continues under sultanate but its nature changes they allowed fuedalism to coexist. www.classmateacademy.com 126 North India (A.D750 –A.D950) Period of Triangular Conflict –Pala,Prathihara,Rashtrakutas Gurjara Prathiharas-West Pala –Pataliputra • Naga Bhatta -1 ,defends wetern border • Started by Gopala • Mihira bhoja (Most powerful) • Dharmapala –most powerful,Patron of Buddhism • Capital -Kannauj Est.Vikramshila university Senas • Vijayasena founder • • Last ruler –Laxmana sena Rashtrakutas defeated by • Dantidurga-founder, • Bhakthiyar Khalji(A.D1206) defeated Badami Chalukyas (Dasavatara Cave) • Krishna-1 Vesara School of architecture • Amoghvarsha Rajputs and Kayasthas the new castes of Medival India New capital-Manyaketa Patron-Jainism &Kannada Famous works-Kavirajamarga,Ratnamalika • Krishna-3 last powerful ruler www.classmateacademy.com 127 www.classmateacademy.com 128 www.classmateacademy.com 129 www.classmateacademy.com 130 www.classmateacademy.com 131 Period of mutlicornered conflict-the 4 Agni Kulas(AD950-AD1206) Chauhans-Ajayameru(Ajmer) Solankis Pawars Ghadwala of Kannauj • Prithviraj chauhan-3 Patronn of Jainsim Bhoja Deva -23 classical Jayachandra (last) • PrthvirajRasok-ChandBardai Dilwara temples of Mt.Abu works in sanskrit • Battle of Tarain-1 Nagara school • Battle of tarain-2(1192) Chandellas of bundelKhand Tomars of Delhi Kajuraho AnangaPal _Dillika www.classmateacademy.com 132 Meanwhile in South India.. -

Kim 1.1.3 Qnm 2014 15 Bos Hs

The panel members gave the following suggestions and recommendations: UG History Changes S. No Sem Course Code Course Title Removed (if any) Addition (if any) Unit I: Pre- and Proto-Historic India Unit I: Pre and Proto Historic Period Harappa Culture, Vedic Civilization, early and Latter Vedic Mesolithic Age, Proto Historic Period, Indus Valley Age, Epic Period, Map: Important sites of Harappan culture. Civilization, Sangam Age, Map: Important sites of Stone Unit II: The Age of Religious Movements and Foreign ages and Indus Valley Civilization – First Urbanization. Invasions; - Impact of Foreign invasions Unit II: Historic Period Unit III: The Birth of Empires in North India Rise of Magadha, Vedic Age: Early and Later Vedic Period, Aasivagam, - Asoka‟s Achievements and his contribution to Buddhism Rise of States – Sixteen Mahajanapadas – Magatha State; Unit IV: The Great Empires of North India Map: Important places related to Aasivagam. Mahayana Buddhism - Cultural Development under Kushanas Unit III: Mauryan Period Gandhara School of Art - Rise and fall of Gupta Empire; Chandragupta Maurya, Bindusara and other rulers; Sources - Administration, Art and Cultural development under Ashoka‟s Dhamma Policy – Minor and Major Rock and Ancient History of India 1 I 14UHS130201 the Guptas - Revival of Sanskrit decline of Gupta Empire. Map: Pillar Edicts. (upto AD 712.) 1. Kanishka‟s Empire, 2. Samudra Gupta‟s Southern Expedition Unit IV: Post Mauryan Period. 3. Gupta Empire Sungas – Kanvas – Kalingas – Satavahanas – Invasions: Unit V:The Last Native Empire of North India Indo Greeks – Sakas – Parthians – Second Urbanization The Age of Harsha; Harsha and Buddism - Impact of Harsha‟s Map: Important Places related to Second Urbanization death – Origin of Rajput‟s and their culture - - Impact of Arab Unit V: Gupta and Post Gupta Period: Gupta Dynasty: conquest - Causes for the End of Native Empire. -

Ancient Civilizations

1 Chapter – 1 Ancient Civilizations Introduction - The study of ancient history is very interesting. Through it we know how the origin and evolution of human civilization, which the cultures prevailed in different times, how different empires rose uplifted and declined how the social and economic system developed and what were their characteristics what was the nature and effect of religion, what literary, scientific and artistic achievements occrued and thease elements influenced human civilization. Since the initial presence of the human community, many civilizations have developed and declined in the world till date. The history of these civilizations is a history of humanity in a way, so the study of these ancient developed civilizations for an advanced social life. Objective - After teaching this lesson you will be able to: Get information about the ancient civilizations of the world. Know the causes of development along the bank of rivers of ancient civilizations. Describe the features of social and political life in ancient civilizations. Mention the achievements of the religious and cultural life of ancient civilizations. Know the reasons for the decline of various civilizations. Meaning of civilization The resources and art skills from which man fulfills all the necessities of his life, are called civilization. I.e. the various activities of the human being that provide opportunities for sustenance and safe living. The word 'civilization' literally means the rules of those discipline or discipline of those human behaviors which lead to collective life in human society. So civilization may be called a social discipline by which man fulfills all his human needs. -

Chapter Ii History

CHAPTER II HISTORY ANCIENT PERIOD The archaeological discoveries prove that the region of Panipat was inhabited by human beings from very earlier times and had been the centre of vigorous cultural and political activity. We know from the hymns of the Rigveda (VII, 18,19; V.52,17) that the Bharatas of the Saraswati Valley held sway up to the Yamuna river and defeated Ajas, Sigrus and Yaksus1. The archaeological heritage of Panipat region can be divided into pre-historic, proto-historic and historical phases. The extent of archaeological sites of Panipat district, numbering 63, can be classified into Pre-Harappan, Harappan, Late Harappan, Painted Grey Ware (PGW), Grey Ware, Early Historical, Early Medieval and Medieval periods2. Alexander Cunningham and Rodgers were the first archaeologists who collected some relics specially coins from a few sites of Panipat. But it was in the year 1952 that B. B. Lal of Archaeological Survey of India discovered Painted Grey Ware and Northern Black Polished Ware from the mounds of Panipat and Sonepat. S. B. Chaudhary also discovered the Painted Grey Ware at Baholi, 13 kilometres to north-west of Panipat3. Subsequent archaeological explorations conducted by a number of archaeologists and recent explorations along the right bank of River Yamuna conducted under the supervision of C. Dorje have resulted to the discovery of Dull Red Ware in Garsh Sanrai in Panipat Tehsil and Red Ware, Red Polished Ware and Dull Red Ware in Jaurasi Khalsa in Samalkha Tehsil of Panipat district. These explorations have brought to light several ancient mounds containing the relics of bygone history4. -

Bengaluru & Trivandrum

HISTORY OPTIONAL (BENGALURU & TRIVANDRUM) TEST BATCH 2021 Page 1 HISTORY - TEST BATCH SCHEDULE – 2021 (BENGALURU/TRIVANDRUM) 1. The proposed 8 tests will cover 75% of the optional syllabus 2. Tests will cover ancient and medieval India topics and it will help the prelims preparation too. 3. Each test will be for 150 marks with a time duration of 2 hrs 4.The tests will be conducted weekly TEST NO DATE TOPICS TOPICS IN PAPER 1. Sources: Archaeological sources: Exploration, excavation, epigraphy, numismatics, monuments Literary sources: Indigenous: Primary and secondary; poetry, scientific literature, literature, literature in regional languages, religious literature. Foreign accounts: Greek, Chinese and Arab writers. 2. Pre-history and Proto-history: Geographical factors; hunting and Ancient India gathering (paleolithic and mesolithic); Beginning of agriculture TEST 1 21.06.2021 (neolithic and chalcolithic). Modules 1-4 3. Indus Valley Civilization: Origin, date, extent, characteristics, decline, survival and significance, art and architecture. 4. Megalithic Cultures: Distribution of pastoral and farming cultures outside the Indus, Development of community life, Settlements, Development of agriculture, Crafts, Pottery, and Iron industry. Page 2 5. Aryans and Vedic Period: Expansions of Aryans in India. Vedic Period: Religious and philosophic literature; Transformation from Rig Vedic period to the later Vedic period; Political, social and economical life; Significance of the Vedic Age; Evolution of Monarchy and Varna system. 6. Period of Mahajanapadas: Formation of States (Mahajanapada): Republics and monarchies; Rise of urban centres; Trade routes; Economic growth; Introduction of coinage; Spread of Jainism and Buddhism; Rise of Magadha and Nandas. Iranian and Macedonian Ancient India TEST 2 28.06.2021 invasions and their impact. -

Syllabus for History Paper-I & Ii for Manipur Civil Services Combined

SYLLABUS FOR HISTORY PAPER-I & II FOR MANIPUR CIVIL SERVICES COMBINED COMPETITIVE (MAIN) EXAMINATION --- Paper-I Section-A 1. Sources and approaches to study of early Indian history. 2. Early pastoral and agricultural communities. The archaeological evidence. 3. The Indus Civilization: its origins, nature and decline. 4. Patterns of settlement, economy, social organization and religion in India (c. 2000 to 500 B.C.) : archaeological perspectives. 5. Evolution of north Indian society and culture: evidence of Vedic texts (Samhitas to Sutras). 6. Teachings of Mahavira and Buddha. Contemporary society. Early phase of state formation and urbanization. 7. Rise of Magadha; the Mauryan empire. Ashoka's inscriptions; his dhamma. Nature of the Mauryan state. 8-9 Post-Mauryan period in northern and peninsular India: Political and administrative history,. Society, economy, culture and religion. Tamilaham and its society: the Sangam texts. 10-11 India in the Gupta and post-Gupta period (to c. 750) : Political histroy of northern and peninsular India; Samanta system and changes in political structure; economy; social structure; culture; religion. 12. Themes in early Indian cultural history: languages and texts; major stages in the evolution of art and architecture; major philosphical thinkers and schools; ideas in science and mathematics. Section-B 13. India, 750-1200 : Polity, society and economy. Major dynasties and political structurs in North India. Agrarian structures. " Indian feudalism". Rise of Rajputs. The Imperial Cholas and their contemporaries in Peninsular India. Villagle communities in the South. Conditions fof women. Commerce mercantile groups and guilds; towns. Problem of coinage. Arab conquest of Sind; the Ghaznavide empire. 14. India, 750-1200: Culture, Literature, Kalhana, historian. -

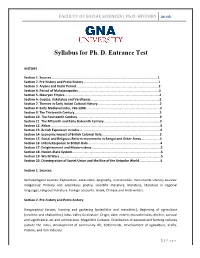

Phd Syllabus History

FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES | Ph.D. HISTORY !"#$ Syllabus for Ph. D. Entrance Test HISTORY Section 1. Sources……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Section 2. Pre-history and Proto-history…………………………………………………………………………….1 Section 3. Aryans and Vedic Period…………………………………………………………………………………….2 Section 4. Period of Mahajanapadas…………………………………………………………………………………..2 Section 5. Mauryan Empire………………………………………………………………….……………………………..2 Section 6. Guptas, Vakatakas and Vardhanas………………………………………………………………………2 Section 7. Themes in EarLy Indian CuLtural History……………………………………………………………….2 Section 8. EarLy Medieval India, 750-1200…………………………………………………………………………...2 Section 9. The Thirteenth Century……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Section 10. The Fourteenth Century…………………………………………………………………………………….3 Section 11. The Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Century…………………………………………………………3 Section 12. Akbar…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Section 13. British Expansion in India…………………………………………………………………………………..4 Section 14. Economic Impact of British CoLonial RuLe……………………………………………………….….2 Section 15. Social and ReLigious Reform movements in Bengal and Other Areas………………….4 Section 16. Indian Response to British RuLe………………………………………………………………………….4 Section 17. EnLightenment and Modern ideas……………………………………………………………………...5 Section 18. Nation-State System……………………………………………………………………………………….….5 Section 19. WorLd Wars………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 Section 20. Disintegration of Soviet Union and the Rise of the UnipoLar WorLd…………………….5 Section 1. Sources: Archaeological