The Church of Scotland's Entry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Rise, Progress, Genius, and Character

v A HISTORY JAN 22 1932 &+*. A fo L SFVA^ OF THE RISE, PROGRESS, GENIUS, AND CHARACTER OF AMERICAN PRESRYTERIANISIfl: TOGETHSB WITH A REVIEW OF "THE CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OP THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, BY CHAS. HODGE, D. D. PROFESSOR IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, AT PRINCETON, N. J." BY WILLIAM HILL, D. D. OF WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA. WASHINGTON CITY: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BT J. GIDEON, jn. 1839. 1 Entered according to the Act of Congress, on the fourteenth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and thirty-nine, by Jacob Gideojj, jr. in the Clerk's office of the District Court for the District of Columbia. — CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Reference to the present divided state of the Presbyterian Church—The loose and un- guarded manner in which Professor Hodge uses the term Presbyterian—The trua meaning of the terms Puritan and Presbyterian—Quotation from Dr. Miller upon th« subject—Professor Hodge claims the majority of the Puritans in England, and of the Pilgrims who first settled New England, as good Presbyterians, and as agreeing with the strict Scotch system—What the Scotch system of strict Presbyterianism is The Presbyterianism of Holland—The Presbyterianism of the French Protestants Professor Hodge's misrepresentation of them corrected by a quotation from Neal's History ; also, from Mosheim and others—The character of the English Presbyte- rians—The true character of the Puritans who settled New England—The kind of Church Government they introduced among them—The Cambridge Platform Quotations from it—Professor Hodge's misunderstanding of it—The Saybrook Plat- form also misrepresented —Cotton Mather's account of the first Presbyterians in New England misrepresented by Professor Hodge—Dr. -

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Socialism and Education in Britain 1883 -1902

Socialism and Education in Britain 1883 -1902 by Kevin Manton A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) Institute of Education University of London September 1998 (i.omcN) 1 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the policies of the socialist movement in the last two decades of the nineteenth century with regard to the education of children. This study is used to both reassess the nature of these education policies and to criticise the validity of the historiographical models of the movement employed by others. This study is thematic and examines the whole socialist movement of the period, rather than a party or an individual and as such draws out the common policies and positions shared across the movement. The most central of these was a belief that progress in what was called the 'moral' and the 'material' must occur simultaneously. Neither the ethical transformation of individuals, nor, the material reformation of society alone would give real progress. Children, for example, needed to be fed as well as educated if the socialist belief in the power of education and the innate goodness of humanity was to be realised. This belief in the unity of moral and material reform effected all socialist policies studied here, such as those towards the family, teachers, and the content of the curriculum. The socialist programme was also heavily centred on the direct democratic control of the education system, the ideal type of which actually existed in this period in the form of school boards. The socialist programme was thus not a utopian wish list but rather was capable of realisation through the forms of the state education machinery that were present in the period. -

Chaplaincy in a New Scottish University: the Issue Ofworship I

T Chaplaincy in a New Scottish University: The Issue ofWorship Christine M. Goldie "'r' The Starting Point I. My starting point is my experience as chaplain at Glasgow Polytechnic, later Glasgow Caledonian University, a post to which I was appointed in March 1992. I had previously served as the minister of St Cuthbert's Church in Clydebank, having been ordained to the ministry and inducted to that charge in May 1984. Almost as soon as I had been introduced as the first full-time chaplain to the Polytechnic, I began to sense uncertainties in my role. In retrospect, I believe I was actually fairly certain of my role. The Polytechnic authorities, however, saw my role differently, and the Church of Scotland, as whose minister I went to the Polytechnic, by virtue of my ordination (even if the Church was paying only a small proportion of my salary), differently again. Two early experiences, one of which occurred almost right away, and the second taking place a year after the first, helped me to realise that these uncertainties, or tensions, focused on my role as a worship leader. In particular, awkward negotiations prior to two quite different worship events - both involving the university administration and church authorities - convinced me that these tensions were connected to complex problems related to structure and theology, which in turn were connected to the different expectations of university and church. At the beginning of my study for the Doctor of Ministry degree in 1996, I was still wrestling with the problem of worship in the university setting, for it had become a problem, at least for me. -

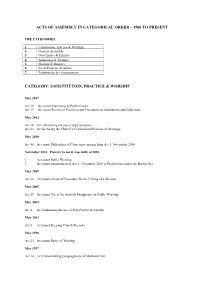

Acts of Assembly in Categorical Order – 1980 to Present

ACTS OF ASSEMBLY IN CATEGORICAL ORDER – 1980 TO PRESENT THE CATEGORIES 1. Constitution, Practice & Worship 2. General Assembly 3. Governance & Finance 4. Admission & Training 5. Mission & Ministry 6. Local Property & Assets 7. Presbyteries & Congregations CATEGORY: CONSTITUTION, PRACTICE & WORSHIP May 2017 Act 18 Act anent Reprinting of Psalm Books Act 19 Act anent Review of Practices and Procedures at Ordinations and Inductions May 2012 Act 16 Act authorising the use of Sing Scripture Act 22 Act declaring the Church’s Confessional Position on Marriage May 2010 Act 48 Act anent Difficulties of Conscience arising from Act 1, November 2010 November 2010 Plenary General Assembly of 2010 1. Act anent Public Worship 2. Act anent transmission of Act 1, November 2010 to Presbyteries under the Barrier Act May 2009 Act 30 Act anent review of Procedure for the Calling of a Minister May 2005 Act 29 Act anent Use of the Scottish Paraphrases in Public Worship May 2003 Act 4 Act authorising the use of Sing Psalms in worship May 2002 Act 5 Act anent Keeping Church Records May 1998 Act 24 Act anent Purity of Worship May 1997 Act 14 Act Consolidating Congregations of Mull and Coll May 1996 Act 16 Act anent Eligibility for Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2 1985, Section 4) Act 17 Act anent Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2, 1985, Section 4) Act 24 Act anent Procedures in relation to Calls May 1994 Act 8 Act anent The Practice – Supplement to Chapter on Discipline May 1992 Act 6 Act anent Supplementary Versions of the Psalms May -

Melrose: the Church and Parish of S

Melrose: The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert 19 Melrose : The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert ON the soil of Melrose Christian worship has been offered up for fully thirteen hundred years. The congregation of Melrose S. Cuthbert's Parish Church can thus trace its spiritual ancestry throughout that period by links which, if not formal, may justly be described as organic, by way of the Reformation to the famous Cistercian Abbey, and thence to the ancient Celtic monastery at Old Melrose two and a half miles away. The Celtic Monastery : The Monks of S. Cuthbert Old Melrose is little known and still less frequented. On the road between Leaderfoot and Dryburgh at its highest point of vantage, now known as " Scott's View ", Sir Walter was accustomed to halt, both to rest his horses and himself to enjoy the romantic landscape. From that point one looks across Tweed to a broad tongue of land almost enclosed by a loop of the river, with the Eildon Hills behind sheltering the place from the prevailing south-west winds. This tongue of land is Old Melrose. Here in the early part of the seventh century the Celtic monastery was founded, reputedly by S. Aidan of Iona himself, and quite surely at his instance, with a colony of monks deriving from Columba's own monastery. Here also Cuthbert, Celtic " Apostle of the Borders ", Roman Bishop of Hexham, anchorite of Lindisfarne and saint, entered on his novitiate. It is recorded by the Rev. Adam Milne, a minister of the parish during the first half of the eighteenth century, that in his day stones of the enclosing cincture of the monastery were still to be seen above ground. -

The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow

Servants to St. Mungo: The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow by Daniel MacLeod A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Daniel MacLeod, May, 2013 ABSTRACT SERVANTS TO ST MUNGO: THE CHURCH IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY GLASGOW Daniel MacLeod Advisors: University of Guelph, 2013 Dr. Elizabeth Ewan Dr. Peter Goddard This thesis investigates religious life in Glasgow, Scotland in the sixteenth century. As the first full length study of the town’s Christian community in this period, this thesis makes use of the extant Church documents to examine how Glaswegians experienced Christianity during the century in which religious change was experienced by many communities in Western Europe. This project includes research from both before and after 1560, the year of the Reformation Parliament in Scotland, and therefore eschews traditional divisions used in studies of this kind that tend to view 1560 as a major rupture for Scotland’s religious community. Instead, this study reveals the complex relationships between continuity and change in Glasgow, showing a vibrant Christian community in the early part of the century and a changed but similarly vibrant community at the century’s end. This project attempts to understand Glasgow’s religious community holistically. It investigates the institutional structures of the Church through its priests and bishops as well as the popular devotions of its parishioners. It includes examinations of the sacraments, Church discipline, excommunication and religious ritual, among other Christian phenomena. The dissertation follows many of these elements from their medieval Catholic roots through to their Reformed Protestant derivations in the latter part of the century, showing considerable links between the traditions. -

William Morris's Culture of Nature

IV The Object of Work 1. Decent surroundings It has been well-established that during the mid to late 1870s Morris became increasingly involved in public political debate, I and that in lectures and letters to the press he began to produce an educating, agitating discourse formulated initially upon his 'hopes and fears for art'.2 More recently, particular attention has been drawn to the ways that Morris's writings on art and society reveal 'a deep and resonant late nineteenth-century critique of contemporary environmental and social devastation'? These discussions have explored Morris's views on the preservation of 'the environment',4 and have tended to emphasise the 'eco-communal' or 'green' aspects of his work. Certainly the desire to protect and preserve the 'beauty of the earth' is a significant feature of Morris's rhetoric at this time. Yet perhaps more fundamental to his lectures and letters of the late 1870s and early 1880s is a concern to establish 'decent surroundings': to offer a view of the earth as a place of human habitation. Nature played an important, though not always central, role in his arguments. Yet what is apparent from the way he discusses nature is his increasing awareness that nature and humanity are interlinked, and that nature is frequently the object of human I Morris's first venture into politics was his involvement in the debate surrounding the 'Eastern Question'. In early 1876 a bankrupt Turkish government retaliated against an uprising of Christians in their Bulgarian province by massacring thousands. Morris was angered when Disraeli's Conservative Government proposed that Britain should intervene on behalf of Turkey against the threat of a Russian invasion. -

Who, Where and When: the History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow

Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow Compiled by Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond © University of Glasgow, Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond, 2001 Published by University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ Typeset by Media Services, University of Glasgow Printed by 21 Colour, Queenslie Industrial Estate, Glasgow, G33 4DB CIP Data for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 0 85261 734 8 All rights reserved. Contents Introduction 7 A Brief History 9 The University of Glasgow 9 Predecessor Institutions 12 Anderson’s College of Medicine 12 Glasgow Dental Hospital and School 13 Glasgow Veterinary College 13 Queen Margaret College 14 Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama 15 St Andrew’s College of Education 16 St Mungo’s College of Medicine 16 Trinity College 17 The Constitution 19 The Papal Bull 19 The Coat of Arms 22 Management 25 Chancellor 25 Rector 26 Principal and Vice-Chancellor 29 Vice-Principals 31 Dean of Faculties 32 University Court 34 Senatus Academicus 35 Management Group 37 General Council 38 Students’ Representative Council 40 Faculties 43 Arts 43 Biomedical and Life Sciences 44 Computing Science, Mathematics and Statistics 45 Divinity 45 Education 46 Engineering 47 Law and Financial Studies 48 Medicine 49 Physical Sciences 51 Science (1893-2000) 51 Social Sciences 52 Veterinary Medicine 53 History and Constitution Administration 55 Archive Services 55 Bedellus 57 Chaplaincies 58 Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery 60 Library 66 Registry 69 Affiliated Institutions -

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Glasgow February 1978 ProQuest Number: 13804140 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804140 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contents Acknowledgments iii Abbreviations iv Notes on dating and currency vii Abstract viii Introduction to the society of Glasgow: its environment, constitution and institutions. 1 Prelude: the formation of parties in Glasgow, 1645-8 30 PART ONE The struggle for Kirk and King, 1648-52 Chapter 1 The radical ascendancy in Glasgow from October 1648 to the fall of the Western Association in December 1650. 52 Chapter II The time of trial: the revival of malignancy in Glasgow, and the last years of the radical Councils, December 1650 - March 1652. 70 PART TWO Glasgow under the Cromwellian Union, 1652-60 Chapter III A malignant re-assessment: the conservative rule in Glasgow, 1652-5. -

Parishes and Congregations: Names No Longer in Use

S E C T I O N 9 A Parishes and Congregations: names no longer in use The following list updates and corrects the ‘Index of Discontinued Parish and Congregational Names’ in the previous online section of the Year Book. As before, it lists the parishes of the Church of Scotland and the congregations of the United Presbyterian Church (and its constituent denominations), the Free Church (1843–1900) and the United Free Church (1900–29) whose names have completely disappeared, largely as a consequence of union. This list is not intended to be ‘a comprehensive guide to readjustment in the Church of Scotland’. Its purpose is to assist those who are trying to identify the present-day successor of a former parish or congregation whose name is now wholly out of use and which can therefore no longer be easily traced. Where the former name has not disappeared completely, and the whereabouts of the former parish or congregation may therefore be easily established by reference to the name of some existing parish, the former name has not been included in this list. Present-day names, in the right-hand column of this list, may be found in the ‘Index of Parishes and Places’ near the end of the book. The following examples will illustrate some of the criteria used to determine whether a name should be included or not: • Where all the former congregations in a town have been united into one, as in the case of Melrose or Selkirk, the names of these former congregations have not been included; but in the case of towns with more than one congregation, such as Galashiels or Hawick, the names of the various constituent congregations are listed.