Chaplaincy in a New Scottish University: the Issue Ofworship I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Rise, Progress, Genius, and Character

v A HISTORY JAN 22 1932 &+*. A fo L SFVA^ OF THE RISE, PROGRESS, GENIUS, AND CHARACTER OF AMERICAN PRESRYTERIANISIfl: TOGETHSB WITH A REVIEW OF "THE CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OP THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, BY CHAS. HODGE, D. D. PROFESSOR IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, AT PRINCETON, N. J." BY WILLIAM HILL, D. D. OF WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA. WASHINGTON CITY: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BT J. GIDEON, jn. 1839. 1 Entered according to the Act of Congress, on the fourteenth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and thirty-nine, by Jacob Gideojj, jr. in the Clerk's office of the District Court for the District of Columbia. — CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. Reference to the present divided state of the Presbyterian Church—The loose and un- guarded manner in which Professor Hodge uses the term Presbyterian—The trua meaning of the terms Puritan and Presbyterian—Quotation from Dr. Miller upon th« subject—Professor Hodge claims the majority of the Puritans in England, and of the Pilgrims who first settled New England, as good Presbyterians, and as agreeing with the strict Scotch system—What the Scotch system of strict Presbyterianism is The Presbyterianism of Holland—The Presbyterianism of the French Protestants Professor Hodge's misrepresentation of them corrected by a quotation from Neal's History ; also, from Mosheim and others—The character of the English Presbyte- rians—The true character of the Puritans who settled New England—The kind of Church Government they introduced among them—The Cambridge Platform Quotations from it—Professor Hodge's misunderstanding of it—The Saybrook Plat- form also misrepresented —Cotton Mather's account of the first Presbyterians in New England misrepresented by Professor Hodge—Dr. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Acts of Assembly in Categorical Order – 1980 to Present

ACTS OF ASSEMBLY IN CATEGORICAL ORDER – 1980 TO PRESENT THE CATEGORIES 1. Constitution, Practice & Worship 2. General Assembly 3. Governance & Finance 4. Admission & Training 5. Mission & Ministry 6. Local Property & Assets 7. Presbyteries & Congregations CATEGORY: CONSTITUTION, PRACTICE & WORSHIP May 2017 Act 18 Act anent Reprinting of Psalm Books Act 19 Act anent Review of Practices and Procedures at Ordinations and Inductions May 2012 Act 16 Act authorising the use of Sing Scripture Act 22 Act declaring the Church’s Confessional Position on Marriage May 2010 Act 48 Act anent Difficulties of Conscience arising from Act 1, November 2010 November 2010 Plenary General Assembly of 2010 1. Act anent Public Worship 2. Act anent transmission of Act 1, November 2010 to Presbyteries under the Barrier Act May 2009 Act 30 Act anent review of Procedure for the Calling of a Minister May 2005 Act 29 Act anent Use of the Scottish Paraphrases in Public Worship May 2003 Act 4 Act authorising the use of Sing Psalms in worship May 2002 Act 5 Act anent Keeping Church Records May 1998 Act 24 Act anent Purity of Worship May 1997 Act 14 Act Consolidating Congregations of Mull and Coll May 1996 Act 16 Act anent Eligibility for Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2 1985, Section 4) Act 17 Act anent Trials for Licence (modifying Act 20, Class 2, 1985, Section 4) Act 24 Act anent Procedures in relation to Calls May 1994 Act 8 Act anent The Practice – Supplement to Chapter on Discipline May 1992 Act 6 Act anent Supplementary Versions of the Psalms May -

Melrose: the Church and Parish of S

Melrose: The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert 19 Melrose : The Church and Parish of S. Cuthbert ON the soil of Melrose Christian worship has been offered up for fully thirteen hundred years. The congregation of Melrose S. Cuthbert's Parish Church can thus trace its spiritual ancestry throughout that period by links which, if not formal, may justly be described as organic, by way of the Reformation to the famous Cistercian Abbey, and thence to the ancient Celtic monastery at Old Melrose two and a half miles away. The Celtic Monastery : The Monks of S. Cuthbert Old Melrose is little known and still less frequented. On the road between Leaderfoot and Dryburgh at its highest point of vantage, now known as " Scott's View ", Sir Walter was accustomed to halt, both to rest his horses and himself to enjoy the romantic landscape. From that point one looks across Tweed to a broad tongue of land almost enclosed by a loop of the river, with the Eildon Hills behind sheltering the place from the prevailing south-west winds. This tongue of land is Old Melrose. Here in the early part of the seventh century the Celtic monastery was founded, reputedly by S. Aidan of Iona himself, and quite surely at his instance, with a colony of monks deriving from Columba's own monastery. Here also Cuthbert, Celtic " Apostle of the Borders ", Roman Bishop of Hexham, anchorite of Lindisfarne and saint, entered on his novitiate. It is recorded by the Rev. Adam Milne, a minister of the parish during the first half of the eighteenth century, that in his day stones of the enclosing cincture of the monastery were still to be seen above ground. -

The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow

Servants to St. Mungo: The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow by Daniel MacLeod A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Daniel MacLeod, May, 2013 ABSTRACT SERVANTS TO ST MUNGO: THE CHURCH IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY GLASGOW Daniel MacLeod Advisors: University of Guelph, 2013 Dr. Elizabeth Ewan Dr. Peter Goddard This thesis investigates religious life in Glasgow, Scotland in the sixteenth century. As the first full length study of the town’s Christian community in this period, this thesis makes use of the extant Church documents to examine how Glaswegians experienced Christianity during the century in which religious change was experienced by many communities in Western Europe. This project includes research from both before and after 1560, the year of the Reformation Parliament in Scotland, and therefore eschews traditional divisions used in studies of this kind that tend to view 1560 as a major rupture for Scotland’s religious community. Instead, this study reveals the complex relationships between continuity and change in Glasgow, showing a vibrant Christian community in the early part of the century and a changed but similarly vibrant community at the century’s end. This project attempts to understand Glasgow’s religious community holistically. It investigates the institutional structures of the Church through its priests and bishops as well as the popular devotions of its parishioners. It includes examinations of the sacraments, Church discipline, excommunication and religious ritual, among other Christian phenomena. The dissertation follows many of these elements from their medieval Catholic roots through to their Reformed Protestant derivations in the latter part of the century, showing considerable links between the traditions. -

Who, Where and When: the History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow

Who, Where and When: The History & Constitution of the University of Glasgow Compiled by Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond © University of Glasgow, Michael Moss, Moira Rankin and Lesley Richmond, 2001 Published by University of Glasgow, G12 8QQ Typeset by Media Services, University of Glasgow Printed by 21 Colour, Queenslie Industrial Estate, Glasgow, G33 4DB CIP Data for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 0 85261 734 8 All rights reserved. Contents Introduction 7 A Brief History 9 The University of Glasgow 9 Predecessor Institutions 12 Anderson’s College of Medicine 12 Glasgow Dental Hospital and School 13 Glasgow Veterinary College 13 Queen Margaret College 14 Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama 15 St Andrew’s College of Education 16 St Mungo’s College of Medicine 16 Trinity College 17 The Constitution 19 The Papal Bull 19 The Coat of Arms 22 Management 25 Chancellor 25 Rector 26 Principal and Vice-Chancellor 29 Vice-Principals 31 Dean of Faculties 32 University Court 34 Senatus Academicus 35 Management Group 37 General Council 38 Students’ Representative Council 40 Faculties 43 Arts 43 Biomedical and Life Sciences 44 Computing Science, Mathematics and Statistics 45 Divinity 45 Education 46 Engineering 47 Law and Financial Studies 48 Medicine 49 Physical Sciences 51 Science (1893-2000) 51 Social Sciences 52 Veterinary Medicine 53 History and Constitution Administration 55 Archive Services 55 Bedellus 57 Chaplaincies 58 Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery 60 Library 66 Registry 69 Affiliated Institutions -

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Glasgow February 1978 ProQuest Number: 13804140 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804140 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contents Acknowledgments iii Abbreviations iv Notes on dating and currency vii Abstract viii Introduction to the society of Glasgow: its environment, constitution and institutions. 1 Prelude: the formation of parties in Glasgow, 1645-8 30 PART ONE The struggle for Kirk and King, 1648-52 Chapter 1 The radical ascendancy in Glasgow from October 1648 to the fall of the Western Association in December 1650. 52 Chapter II The time of trial: the revival of malignancy in Glasgow, and the last years of the radical Councils, December 1650 - March 1652. 70 PART TWO Glasgow under the Cromwellian Union, 1652-60 Chapter III A malignant re-assessment: the conservative rule in Glasgow, 1652-5. -

Parishes and Congregations: Names No Longer in Use

S E C T I O N 9 A Parishes and Congregations: names no longer in use The following list updates and corrects the ‘Index of Discontinued Parish and Congregational Names’ in the previous online section of the Year Book. As before, it lists the parishes of the Church of Scotland and the congregations of the United Presbyterian Church (and its constituent denominations), the Free Church (1843–1900) and the United Free Church (1900–29) whose names have completely disappeared, largely as a consequence of union. This list is not intended to be ‘a comprehensive guide to readjustment in the Church of Scotland’. Its purpose is to assist those who are trying to identify the present-day successor of a former parish or congregation whose name is now wholly out of use and which can therefore no longer be easily traced. Where the former name has not disappeared completely, and the whereabouts of the former parish or congregation may therefore be easily established by reference to the name of some existing parish, the former name has not been included in this list. Present-day names, in the right-hand column of this list, may be found in the ‘Index of Parishes and Places’ near the end of the book. The following examples will illustrate some of the criteria used to determine whether a name should be included or not: • Where all the former congregations in a town have been united into one, as in the case of Melrose or Selkirk, the names of these former congregations have not been included; but in the case of towns with more than one congregation, such as Galashiels or Hawick, the names of the various constituent congregations are listed. -

Paisley Pamphlets 1739

PAISLEY PAMPHLETS 1739 – 1893 The 'Paisley Pamphlets' are a collection of ephemera rich in social history covering the period 1739 - 1893. Ephemera are items of collectible memorabilia in written or printed form which had only a short period of usefulness or popularity. The pamphlets cover a range of topics, chiefly politics and religion. To make it easy for you to search, we have combined the indexes for all the volumes into this one volume. On the next page we will give you guidance on how to search the index. Searching the Paisley Pamphlets index ➢ Browse pages simply by scrolling up and down ➢ If you are viewing the index online you can click ctrl + f on your keyboard to bring up the search box where you can enter the term you want to search for If you have saved a copy of the PDF to your tablet or PC, and are using Adobe Acrobat Reader to view it, you can use the search tool. Just click on it and enter the term you want to search for. ➢ Your results will start to appear beneath the search box. You can look at any of the entries by clicking on it. ➢ Using either search tool, your results will appear as highlighted text. You can just work through all the matches to see if any of the records are of use to you. Tips! If you are unsure about the spelling or the wording which has been used, you can search under just a few letters e.g. searching “chem” will give you results including chemist, chemistry, chemicals, etc. -

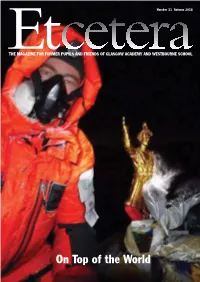

On Top of the World Editorial the Summer Term of an Academic Year Can Be Filled with Mixed Emotions

Number 31 Autumn 2018 On Top of the World Editorial The Summer term of an academic year can be filled with mixed emotions. For many, it means their time either as a pupil or as a member of staff at The Academy has come to Contents an end. This year was particularly special as our two Deputy Heads, Jaqueline Andrews 3 The best of TGA online and Andrew Evans, our Head of PE, Stewart McAslan, Prep School Teacher, Rob 5 Armstrong becomes World Williams, and our Director of External Relations, Malcolm McNaught, began their Champion for the second time retirement journeys. These five highly-regarded and deeply-loyal members of staff collectively served 7 The Glasgow Academy after the The Academy for over 150 years. First World War As readers of Etcetera will appreciate, there are few people who know The Academy as well as Malcolm McNaught: his unique perspective on the school has been formed 8 On top of the world during the 37 years in which he has been the parent of three children who attended 11 Anecdotage the school, member of the English Department and, ultimately, Director of External Relations. 13 Glasgow Academical Club Malcolm taught English 16 Westbourne Section with passion and energy, and is particularly remembered 19 Announcements for his penchant for accents when reading aloud! A 22 Reunions and get-togethers committed, conscientious and 24 Obituaries organised teacher, he always strove to do his best for his pupils and to encourage their self-belief. Malcolm was compassionate, supportive Do we have your e-mail address? and good-humoured, always It’s how we communicate best! able to see the funny side of situations and offer practical and sound advice. -

Church Directory

FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND (CONTINUING) Church Directory 2018 FREE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND (CONTINUING) Church Directory 2018 Assembly Clerks’ Office Free Church Manse Portmahomack IV20 1YL Tel: 01862 871467 Email: [email protected] © Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) 2018 For further copies of the Directory please contact: [email protected] Note:- While it is hoped that the information contained in this Directory is correct at the time of printing (May 2018) details are always subject to change. For up-to-date information please consult the Church website: www.freechurchcontinuing.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Historical Information 1 Other Information 2 General 3 Finance 4 Church Courts 4 Training of Ministers 5 Home Mission Worker 6 Resident Lay Agent 6 Social Responsibility 6 School in Theology 6 Spring Conference 7 All-Age Holiday 7 Audio Ministry 7 Fraternal Organisations 7 2. SCOTLAND 9 Mainland Synod 9 Northern Presbytery 9 Presbytery of Inverness 13 Southern Presbytery 19 Western Synod 27 Presbytery of the Outer Hebrides 27 Presbytery of Skye & Lochcarron 33 3. OVERSEAS AND MISSIONS 40 Overseas 40 Canada 40 United States of America 41 Presbytery of the United States of America 41 Missions 45 Northern Ireland 45 Spain 46 Sri Lanka 47 Other 48 4. INDEXES 49 Ministers 49 Ministers without Charge 52 Resigned Ministers 52 Probationers 52 Clerks to Committees of Assembly 53 Moderators of the General Assembly since 1950 54 Communion Dates 56 Congregations, Places of Worship and Preaching Stations 57 1. INTRODUCTION HISTORICAL INFORMATION The Free Church of Scotland is a Presbyterian Church adhering in its worship and doctrine to the position adopted by the Church of Scotland at the Reformation. -

Another Copy. 2 Vols

GLASGOW. General entries - -- The burgesses & guild brethren of Glasgow, 1573 -1750. Ed. by J.R. Anderson. [Scott. Rec. Soc. Vol. 56 ] Edin., 1925(1923 -25). RK.13. - -- The burgesses and guild brethren of Glasgow, 1751 -1846. Ed. by J.R. Anderson. [Scott. Rec. Soc. Vol. 66.] Edin., 1935(1931 -35). RK.13 . *** Title -page wanting. - -- Burgh records of the city of Glasgow, 1573 -1581. (Ed. by J. Smith.) [Maitland Club, 16.] Glasgow, 1832. RN.6. - -- Charters and other documents relating to the City of Glasgow. 2 vols. (in 3). [Scott. Burgh Rec. Soc. Vols. 14 -15, 17.] Glasgow, Edin. RK.8.14 -15, 17. [1.] A.D. 1175 -1649. Ed. by Sir J.D. Marwick. 2 pts. 1897, 1894. 2. A.D. 1649 -1707. With appendix, A.D. 1434-1648. Ed. by Sir J.D. Marwick and R. Renwick. 1906. *** For later charters see below Extracts from the records of the Burgh of Glasgow. Vols. 5 -7. - -- Another copy. 2 vols. (in 3). Scott. Hist. Lib. - -- Another copy. Vol. 1 (in 2). Scott. Eist. Lib. - -- Another copy. Vol. 1, pt. 2 - vol. 2. Scott. Stud. Lib. - -- Chronicles of St. Munga, or, antiquities and traditions of Glasgow. Glasgow, 1843. .9(41435) Gla. - -- Another copy. Yk.10.23. - -- The City of Glasgow, its origin, growth and development. With maps aid plates. J. Gunn ... honorary editor. M.I. Newbigin ... editor. [Repr. from the Scottish Geographical Magazine, ,1o1.37.] Edin., 1921. Geog. Lib. [Continued overleaf.] GLASGOW [continued]. General entries [continued] - -- Extracts from the records of the Burgh of Glasgow. Vols. 1 -7. Glasgow. [1.] A.D.