198 13. Repulse Bay. This Is an Important Summer Area for Seals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Dear Beaufort: a Personal Letter from John Ross's Arctic Expedition

ARCTIC VOL. 40, NO. 1 (MARCH 1987) P. 66-77 My Dear Beaufort: A Personal Letter from John Ross’s Arctic Expedition of 1829-33 CLIVE HOLLAND’ and JAMES M. SAVELLE2 (Received 30 January 1986; accepted in revised form 6 October 1986) ABSTRACT. During his four years’ residence in the Canadian Arctic in search of a Northwest Passage in 1829-33, John Ross wrote a private letter to Francis Beaufort, Hydrographer of the Navy. The letter, reproduced here, provides valuable historical insights into many aspects of Ross’s character and of the expedition generally. His feelings of bitterness toward several of his contemporaries, especially John Barrow and William E. Parry, due to the ridicule suffered as a result of the failure of his first arctic voyage in 1818, are especially revealing, as is his apparently uneasy relationship with his nephew and second-in-command, James Clark Ross. Ross’s increasing despair andpessimism with each succeeding enforced wintering and, eventually, the abandonment of the expedition ship Victory are also clearly evident. Finally,the understandable problems of maintaining crew discipline during the final year of the expedition, though downplayed, begin to emerge. Key words: John Ross, arctic exploration, 1829-33 Arctic Expedition, unpublished letter RÉSUMÉ. Durant les quatre années où ilr6sidadans l’Arctique canadien à la recherche du Passage du Nord-Ouest, de 1829 à 1833, John Ross écrivit une lettre personnelle à Francis Beaufort, hydrographe de la marine. Cette lettre, reproduite ici, permet de mieux apprécier du point de vue historique, certains aspects du caractère de Ross et de l’expédition en général. -

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

Regional Maps of Locations Mentioned in Global Review of The

Regional Maps of Locations Mentioned in Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks These maps provide the locations of the geographic features mentioned in the Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks. Figure 1. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Okhotsk Sea (beluga stocks 1-5). Numbered locations are: (1) Amur River, (2) Ul- bansky Bay, (3) Tugursky Bay, (4) Udskaya Bay, (5) Nikolaya Bay, (6) Ulban River, (7) Big Shantar Island, (8) Uda River, (9) Torom River. Figure 2. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska (beluga stocks 6-9). Numbered locations are: (1) Anadyr River Estuary, (2) Anadyr River, (3) Anadyr City, (4) Kresta Bay, (5) Cape Navarin, (6) Yakutat Bay, (7) Knik Arm, (8) Turnagain Arm, (9) Anchorage, (10) Nushagak Bay, (11) Kvichak Bay, (12) Yukon River, (13) Kuskokwim River, (14) Saint Matthew Island, (15) Round Island, (16) St. Lawrence Island. Figure 3. Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, Canadian Arctic and West Greenland (beluga stocks 10-12 and 19). Numbered locations are: (1) St. Lawrence Island, (2) Kotzebue Sound, (3) Kasegaluk Lagoon, (4) Point Lay, (5) Wain- wright, (6) Mackenzie River, (7) Somerset Island, (8) Radstock Bay, (9) Maxwell Bay, (10) Croker Bay, (11) Devon Island, (12) Cunning- ham Inlet, (13) Creswell Bay, (14) Mary River Mine, (15) Elwin Bay, (16) Coningham Bay, (17) Prince of Wales Island, (18) Qeqertarsuat- siaat, (19) Nuuk, (20) Maniitsoq, (21) Godthåb Fjord, (22) Uummannaq, (23) Upernavik. Figure 4. Locations associated with beluga stocks of subarctic eastern Canada, Hudson Bay, Ungava Bay, Cumberland Sound and St. -

Green Paper the Lancaster Sound Region

Green Paper The Lancaster Sound Region: 1980-2000 Issues and Options on the Use and Management of the Region Lancaster Sound Regional Study H.J. Dirschl Project Manager January 1982 =Published under the authority of the Hon. John C. Munro, P.C., M.P., Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, 1981. 05-8297-020-EE-A1 Catalogue No. R72-164/ 1982E ISBN 0-662-11869 Cette publication peut aussi etre obtenue en francais. Preface In the quest for a "best plan" for Lancaster Sound criticisms. This feedback is discussed in detail in a and its abundant resources, this public discussion recently puolished report by the workshop chairman. paper seeks to stimulate a continued. wide-ranging, Professor Peter Jacobs, entitled People. Resources examination of the issues involved in the future use and the Environment: Perspectives on the Use and and management of this unique area of the Canadian Management of the Lancaster Sound Region. All the Arctic. input received during the public review phase has been taken into consideration in the preparation of the The green paper is the result of more than two years final green paper. of work by the Northern Affairs Program of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern From the beginning of the study, it was expected that Development, in co-operation with the government of to arrive at an overall consensus of the optimum fu the Northwest Territories and the federal departments ture use and management of the Lancaster Sound of Energy, Mines and Resources, Environment. region would require intensive public discussion fol Fisheries and Oceans. -

NUNAVUT a 100 , 101 H Ackett R Iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C Lve Coal T Rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H Igh Lake , Izo K Lake M M G Resources Inc

150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 100°W 90°W 80°W 70°W 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W PROJECTS BY REGION Note: Bold project number and name signifies major or advancing project. AR CT KITIKMEOT REGION 8 I 0 C LEGEND ° O N umber P ro ject Operato r N O C C E Commodity Groupings ÉA AN B A SE M ET A LS Mineral Exploration, Mining and Geoscience N Base Metals Iron NUNAVUT A 100 , 101 H ackett R iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C lve Coal T rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H igh Lake , Izo k Lake M M G Resources Inc. I n B P Q ay q N Diamond Active Projects 2012 U paa Rare Earth Elements 104 Hood M M G Resources Inc. E inir utt Gold Uranium 0 50 100 200 300 S Q D IA M ON D S t D i a Active Mine Inactive Mine 160 Hammer Stornoway Diamond Corporation N H r Kilometres T t A S L E 161 Jericho M ine Shear Diamonds Ltd. S B s Bold project number and name signifies major I e Projection: Canada Lambert Conformal Conic, NAD 83 A r D or advancing project. GOLD IS a N H L ay N A 220, 221 B ack R iver (Geo rge Lake - 220, Go o se Lake - 221) Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. T dhild B É Au N L Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions E - a PRODUCED BY: B n N ) Committee Bay (Anuri-Raven - 222, Four Hills-Cop - 223, Inuk - E s E E A e ER t K CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply 222 - 226 North Country Gold Corp. -

Stream Sediment and Stream Water OG SU Alberta Geological Survey (MITE) ICAL 95K 85J 95J 85K of 95I4674 85L

Natural Resources Ressources naturelles Canada Canada CurrentCurrent and and Upcoming Upcoming NGR NGR Program Program Activities Activities in in British British Columbia, Columbia, NationalNational Geochemical Geochemical Reconnaissance Reconnaissance NorthwestNorthwest Territories, Territories, Yukon Yukon Territory Territory and and Alberta, Alberta, 2005-06 2005-06 ProgrProgrammeamme National National de de la la Reconnaissance Reconnaissance Géochimique Géochimique ActivitésActivités En-cours En-cours et et Futures Futures du du Programme Programme NRG NRG en en Colombie Colombie Britannique, Britannique, P.W.B.P.W.B. Friske, Friske,S.J.A.S.J.A. Day, Day, M.W. M.W. McCurdy McCurdy and and R.J. R.J. McNeil McNeil auau Territoires Territoires de du Nord-Ouest, Nord-Ouest, au au Territoire Territoire du du Yukon Yukon et et en en Alberta, Alberta, 2005-06 2005-06 GeologicalGeological Survey Survey of of Canada Canada 601601 Booth Booth St, St, Ottawa, Ottawa, ON ON 11 Area: Edéhzhie (Horn Plateau), NT 55 Area: Old Crow, YT H COLU Survey was conducted in conjunction with Survey was conducted in conjunction with and funded by IS M EUB IT B and funded by NTGO, INAC and NRCAN. NORTHWEST TERRITORIES R I the Yukon Geological Survey and NRCAN. Data will form A 124° 122° 120° 118° 116° B Alberta Energy and Utilities Board Data will form the basis of a mineral potential GEOSCIENCE 95N 85O the basis of a mineral potential evaluation as part of a 95O 85N evaluation as part of a larger required 95P 85M larger required Resource Assessment. OFFICE .Wrigley RESEARCH ANALYSIS INFORMATION Resource Assessment. .Wha Ti G 63° YUKON 63° Metals in the Environment (MITE) E Y AGS ESS Program: O E ESS Program: Metals in the Environment V .Rae-Edzo L R GSEOLOGICAL URVEY Survey Type: Stream Sediment and Stream Water OG SU Alberta Geological Survey (MITE) ICAL 95K 85J 95J 85K OF 95I4674 85L Survey Type: Stream Sediment, stream M Year of Collection: 2004 and 2005 A C K ENZI E R 2 62° I V water, bulk stream sediment (HMCs and KIMs). -

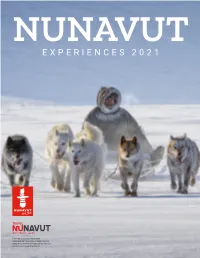

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

Atlantic Walrus Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 23 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Richard, P. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Atlantic walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Northwest Atlantic Population and Eastern Arctic Population) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-23 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the status report on the Atlantic Walrus Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Andrew Trites, Co-chair, COSEWIC Marine Mammals Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation du morse de l'Atlantique (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions ERIC W. DANIELSON, JR.l ABSTRACT.Monthly mean ice cover distributions for Hudson Bay have been derived, based upon an analysis of nine years of aerial reconnaissance and other data. Information is presented in map form, along with diseussian Of significant features. Ice break-up is seen to work southward from the western, northern, and eastern edges of the Bay; the pattern seems to be a result of local topography, cur- rents, and persistent winds. Final melting occurs in August. Freeze-up commences in October, along the northwestern shore, and proceeds southeastward. The entire Bay is ice-covered by early January,except for persistent shore leads. RÉSUMÉ. Conditions de la glace dans la mer d’Hudson. A partir de l’analyse de neuf années de reconnaissances aériennes et d’autres données, on a pu déduire des moyennes mensuelles de distribution de la glace pour la mer d’Hudson. L‘informa- tion est présentte sous formes de cartes et de discussion des Cléments significatifs. On y voit que la débâcle progresse vers le sud à partir des marges ouest, nord et est dela mer; cette séquence sembleêtre le résultat de la topographielocale, des courants et .des vents dominants. La fonte se termine en aofit. L’enge€wommence en octobre le long de la rive nord-ouest et progresse vers le sud-est. Sauf pow les chenaux côtiers persistants, la mer est entihrement gelée au début de janvier. INTRODUCTION In many respects, ice cover is a basic hydrometeorological variable. In Hudson Bay (Fig. 1) it might be considered the most basic of all, as it influences all other conditions so decisively. -

The Southampton Island Marine Ecosystem Project 2019 Cruise

Southampton Island The Southampton Island Marine Ecosystem Project 2019 Cruise Report 5-29 August MV William Kennedy SIMEP 2019 Cruise Report Table of Contents Section 1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. Physical Oceanography .................................................................................. 6 Section 3. Biogeochemistry .......................................................................................... 14 Section 4. Phytoplankton .............................................................................................. 20 Section 5. Kelp .............................................................................................................. 28 Section 6. Zooplankton and Fish .................................................................................. 38 Section 7. Sediments ..................................................................................................... 44 Appendix: Ship Log ...................................................................................................... 49 Appendix: Phyto Net Log ............................................................................................. 71 Appendix: Sediment stations ........................................................................................ 79 SIMEP 2019 Cruise Report Section 1. Introduction Climate warming is forcing rapid change to Canada’s marine Arctic icescape (Hochheim and Barber 2010) and its associated ecosystem, -

Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Narwhal in the Nunavut Settlement Area

Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Narwhal in the Nunavut Settlement Area Hunter & Trapper Organizations Consultations March 2012 Discussion Topics • Why changes are needed to narwhal co-management • Overview of the draft Narwhal Management Plan • Marine Mammal Tag Transfer Policy Development • HTO & hunter roles and responsibilities under the revised management system Why do we need changes to the Narwhal Management System? Increased national and international interest in how the narwhal fishery in Nunavut is managed. Strengthen narwhal co-management consistent with; • NLCA wildlife harvesting and management provisions such as • Establishing Total Allowable Harvest (TAH), Basic Needs Level (BNL) • Increased roles for Regional Wildlife Organizations (RWOs) and Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTOs) • Available scientific and Inuit knowledge • Sustainable harvesting • International trade requirements Why do we need changes to the Narwhal Management System? International Exports • Must conform to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) • Canadian CITES Export Permits require a Non-Detriment Finding (NDF) • In 2010 and 2011, exports of narwhal products from some areas were not allowed • CITES Parties will meet in spring 2013, and may request a review of narwhal trade • If trade is deemed harmful to the survival of the species, trade restrictions or bans could be imposed. • Important that the Narwhal Management Plan is approved and implemented by January 2013 Importance of Improving the Narwhal Management System • Improvements to the narwhal management system will assist • Co-management organizations to clearly demonstrate that narwhal harvesting is sustainable • Continued sustainable harvest for future generations of Inuit • Continued trade/export of narwhal tusks and products from Canada • A formal Management Plan will outline the management objectives for narwhal and the measures to achieve sustainable harvesting. -

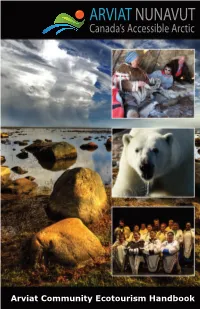

Arviat Community Ecotourism Handbook This Copy Belongs To

Arviat Community Ecotourism Handbook This copy belongs to: Front cover photo credits: Polar bear, Mark Seth Lender Landscape, Michelle Valberg Welcome to Arviat! Arviat is one of the more southerly and most accessible Inuit communities in Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory. Located on the western shores of Hudson Bay, framed in by several large barrenland rivers lies this intriguing land rich in wildlife, a flat to gently rolling landscape dotted with lakes and ponds, and steeped in Inuit culture. Arviat presents the authentic best in Nunavut tourism. If you are looking for a real arctic tourism experience Arviat offers spectacular wildlife viewing combined with an interactive cultural program providing insight into fascinating age old Inuit cultural traditions. Arviammiut (the people of Arviat) are your hosts in this magical land. We are a proud people living in harmony with the land and wildlife around us and we maintain a strong connection with our Inuit traditions and culture. This landscape has been occupied for thousands of years and much of the physical evidence of early occupations still survives due to the Arctic climate. Two National Historic Sites that can be easily accessed from the community are testament to the rich cultural heritage and resources on the land www.historicplaces.ca Come explore the land of the Inuit, with the Inuit. If you are interested in learning more about the Inuit of Arviat you can visit the Nanisiniq website: nanisiniq.tumblr.com Michelle Valberg 1 The Arviat Community Ecotourism (ACE) initiative is true community-based tourism. ACE is owned and operated by the community.