QAQSAUQTUUQ MIGRATORY BIRD SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN [January 2020] Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Special Management Measures for Midcontinent Lesser Snow Geese and Ross’S Geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group

Evaluation of special management measures for midcontinent lesser snow geese and ross’s geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group A Special Publication of the Arctic Goose Joint Venture of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan Evaluation of special management measures for midcontinent lesser snow geese and ross’s geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group A Special Publication of the Arctic Goose Joint Venture of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan Edited by: James O. Leafloor, Timothy J. Moser, and Bruce D.J. Batt Working Group Members James O. Leafloor Co-Chair Canadian Wildlife Service Timothy J. Moser Co-Chair U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bruce D. J. Batt Past Chair Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Kenneth F. Abraham Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Ray T. Alisauskas Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada F. Dale Caswell Canadian Wildlife Service Kevin W. Dufour Canadian Wildlife Service Michel H. Gendron Canadian Wildlife Service David A. Graber Missouri Department of Conservation Robert L. Jefferies University of Toronto Michael A. Johnson North Dakota Game and Fish Department Dana K. Kellett Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada David N. Koons Utah State University Paul I. Padding U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Eric T. Reed Canadian Wildlife Service Robert F. Rockwell American Museum of Natural History Evaluation of Special Management Measures for Midcontinent Snow Geese and Ross's Geese: Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group SUGGESTED citations: Abraham, K. F., R. L. Jefferies, R. T. Alisauskas, and R. F. Rockwell. 2012. Northern wetland ecosystems and their response to high densities of lesser snow geese and Ross’s geese. -

Proceedings Template

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2020/032 Central and Arctic Region Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area in support of the identification of an Area of Interest T.N. Loewen1, C.A. Hornby1, M. Johnson2, C. Chambers2, K. Dawson2, D. MacDonell2, W. Bernhardt2, R. Gnanapragasam2, M. Pierrejean4 and E. Choy3 1Freshwater Institute Fisheries and Oceans Canada 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 2North/South Consulting Ltd. 83 Scurfield Blvd, Winnipeg, MB R3Y 1G4 3McGill University. 845 Sherbrooke Rue, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4 4Laval University Pavillon Alexandre-Vachon 1045, , av. of Medicine Quebec City, QC G1V 0A6 July 2020 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2020 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Loewen, T. N., Hornby, C.A., Johnson, M., Chambers, C., Dawson, K., MacDonell, D., Bernhardt, W., Gnanapragasam, R., Pierrejean, M., and Choy, E. 2020. Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton proposed Area of Interest for the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. -

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions

Hudson Bay Ice Conditions ERIC W. DANIELSON, JR.l ABSTRACT.Monthly mean ice cover distributions for Hudson Bay have been derived, based upon an analysis of nine years of aerial reconnaissance and other data. Information is presented in map form, along with diseussian Of significant features. Ice break-up is seen to work southward from the western, northern, and eastern edges of the Bay; the pattern seems to be a result of local topography, cur- rents, and persistent winds. Final melting occurs in August. Freeze-up commences in October, along the northwestern shore, and proceeds southeastward. The entire Bay is ice-covered by early January,except for persistent shore leads. RÉSUMÉ. Conditions de la glace dans la mer d’Hudson. A partir de l’analyse de neuf années de reconnaissances aériennes et d’autres données, on a pu déduire des moyennes mensuelles de distribution de la glace pour la mer d’Hudson. L‘informa- tion est présentte sous formes de cartes et de discussion des Cléments significatifs. On y voit que la débâcle progresse vers le sud à partir des marges ouest, nord et est dela mer; cette séquence sembleêtre le résultat de la topographielocale, des courants et .des vents dominants. La fonte se termine en aofit. L’enge€wommence en octobre le long de la rive nord-ouest et progresse vers le sud-est. Sauf pow les chenaux côtiers persistants, la mer est entihrement gelée au début de janvier. INTRODUCTION In many respects, ice cover is a basic hydrometeorological variable. In Hudson Bay (Fig. 1) it might be considered the most basic of all, as it influences all other conditions so decisively. -

The Southampton Island Marine Ecosystem Project 2019 Cruise

Southampton Island The Southampton Island Marine Ecosystem Project 2019 Cruise Report 5-29 August MV William Kennedy SIMEP 2019 Cruise Report Table of Contents Section 1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. Physical Oceanography .................................................................................. 6 Section 3. Biogeochemistry .......................................................................................... 14 Section 4. Phytoplankton .............................................................................................. 20 Section 5. Kelp .............................................................................................................. 28 Section 6. Zooplankton and Fish .................................................................................. 38 Section 7. Sediments ..................................................................................................... 44 Appendix: Ship Log ...................................................................................................... 49 Appendix: Phyto Net Log ............................................................................................. 71 Appendix: Sediment stations ........................................................................................ 79 SIMEP 2019 Cruise Report Section 1. Introduction Climate warming is forcing rapid change to Canada’s marine Arctic icescape (Hochheim and Barber 2010) and its associated ecosystem, -

198 13. Repulse Bay. This Is an Important Summer Area for Seals

198 13. Repulse Bay. This is an important summer area for seals (Canadian Wildlife Service 1972) and a primary seal-hunting area for Repulse Bay. 14. Roes Welcome Sound. This is an important concentration area for ringed seals and an important hunting area for Repulse Bay. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 15. Southampton-Coats Island. The southern coastal area of Southampton Island is an important concentration area for ringed seals and is the primary ringed and bearded seal hunting area for the Coral Harbour Inuit. Fisher and Evans Straits and all coasts of Coats Island are important seal-hunting areas in late summer and early fall. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 16.7.2 Communities Affected Communities that could be affected by impacts on seal populations are Resolute and, to a lesser degree, Spence Bay, Chesterfield Inlet, and Gjoa Haven. Effects on Arctic Bay would be minor. Coral Harbour and Repulse Bay could be affected if the Quebec route were chosen. Seal meat makes up the most important part of the diet in Resolute, Spence Bay, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay. It is a secondary, but still important food in Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. Seal skins are an important source of income for Spence Bay, Resolute, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay and a less important income source for Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. 16.7.3 Data Gaps Major data gaps concerning impacts on seal populations are: 1. -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

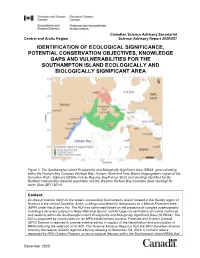

Identification of Ecological Significance, Potential

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Central and Arctic Region Science Advisory Report 2020/057 IDENTIFICATION OF ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE, POTENTIAL CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES, KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND VULNERABILITIES FOR THE SOUTHAMPTON ISLAND ECOLOGICALLY AND BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT AREA Figure 1. The Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA; green shading) within the Hudson Bay Complex (Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait and Foxe Basin) biogeographic region of the Canadian Arctic. Adjacent EBSAs include Repulse Bay/Frozen Strait (red shading) identified for the Northern Hudson Bay Narwhal population and the Western Hudson Bay Coastline (blue shading) for Arctic Char (DFO 2011). Context: An Area of Interest (AOI) for the waters surrounding Southampton Island, located in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut in the central Canadian Arctic, is being considered for designation as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) under the Oceans Act. The AOI was nominated based on the presence of complex oceanography, including a recurrent polynya in Roes Welcome Sound, and for large concentrations of marine mammals and seabirds within the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (SI EBSA). The AOI is supported by communities for an MPA establishment process. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Science is required to provide science advice in support of the identification and prioritization of MPAs following the selection of an AOI. This Science Advisory Report is from the DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) regional advisory meeting of December 5-6, 2018. It contains advice requested by DFO Oceans Program on key ecological features within the Southampton Island EBSA that December 2020 Southampton Island AOI Ecological Central and Arctic Region Significance and potential COs warrant marine protection and recommends conservation objectives. -

Publications in Biological Oceanography, No

National Museums National Museum of Canada of Natural Sciences Ottawa 1971 Publications in Biological Oceanography, No. 3 The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Elizabeth Macpherson CALIFORNIA OF SCIK NCCS ACADEMY |] JAH ' 7 1972 LIBRARY Publications en oceanographie biologique, no 3 Musees nationaux Musee national des du Canada Sciences naturelles 1. Belcher Islands 2. Evans Strait 3. Fisher Strait 4. Southampton Island 5. Roes Welcome Sound 6. Repulse Bay 7. Frozen Strait 8. Foxe Channel 9. Melville Peninsula 10. Frobisher Bay 11. Cumberland Sound 12. Fury and Hecia Strait 13. Boothia Peninsula 14. Prince Regent Inlet 15. Admiralty Inlet 16. Eclipse Sound 17. Lancaster Sound 18. Barrow Strait 19. Viscount Melville Sound 20. Wellington Channel 21. Penny Strait 22. Crozier Channel 23. Prince Patrick Island 24. Jones Sound 25. Borden Island 26. Wilkins Strait 27. Prince Gustaf Adolf Sea 28. Ellef Ringnes Island 29. Eureka Sound 30. Nansen Sound 31. Smith Sound 32. Kane Basin 33. Kennedy Channel 34. Hall Basin 35. Lincoln Sea 36. Chantrey Inlet 37. James Ross Strait 38. M'Clure Strait 39. Dease Strait 40. Melville Sound 41. Bathurst Inlet 42. Coronation Gulf 43. Dolphin and Union Strait 44. Darnley Bay 45. Prince of Wales Strait 46. Franklin Bay 47. Liverpool Bay 48. Mackenzie Bay 49. Herschel Island Map 1 Geographical Distribution of Recorded Specimens CANADA DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, MINES AND RESOURCES CANADASURVEYS AND MAPPING BRANCH A. Southeast region C. North region B. Northeast region D. Northwest region Digitized by tlie Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from California Academy of Sciences Library http://www.archive.org/details/publicationsinbi31nati The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Prosobranch Gastropods, Chitons and Scaphopods National Museum of Natural Sciences Musee national des sciences naturelles Publications in Biological Publications d'oceanographie Oceanography, No. -

BULLETIN No. 88

FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA UNDER THE CONTROL OF THE HON. THE MINISTER OF FISHERIES BULLETIN No. 88 EASTERN ARCTIC WATERS By M.]. DUNBAR Department of Zoology McGill University OTTAWA 1951 , BULLETIN No. 88 EASTERN ARCTIC WATERS , .. \ \'\ '� .� \ \\ \ .'.���� \, /' \)�\ / \ /\ \ General Map of the Eastern Arctic Area FISHERIES RESEARCH BOARD OF CANADA UNDER THE CONTROL OF THE HON. THE MINISTER OF FISHERIES BULLETIN No. 88 EASTERN ARCTIC WATERS A summary of our present knowledge of the physical oceanography of the eastern arctic area, from Hudson bay to cape Farewell and from Belle Isle to Smith sound BY M. J. DUNBAR Department of Zoology McGill University OTTAWA 1951 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND SOURCE MATERIAL 2 BATHYMETRY 20 SEDIMENTS 27 THE WATER MASSES 30 HORIZONTAL DISTRIBUTION OF TEMPERATURE AND SALINITY 38 CIRCULATION 46 FJORDS AND OTHER INLETS 75 SEASONAL CYCLES 94 LONG-TERM CHANGES 98 , ARCTIC' AND SUB-ARCTIC 109 GAPS IN OUR KNOWLEDGE 115 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 119 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 FIGURES General map of the eastern arctic area Frontispiece 1. Bathymetric map 21 2. West Greenland banks 24 3. The water masses of the eastern arctic (T-S diagram) 31 4. Water masses of Hudson strait and Ungava bay 35 5. "Loubyrne" and ,"Haida" Nansen bottle stations 36 6. Ungava bay stations, 1947 37 7-12. Distribution of temperature and salinity at 0, 100, and 800 metres 39-45 13. Surface currents 48 14. "Korth water" of northern Baffin bay, after Kiilerich 58 15. "Haida" bathythermograph stations, 1948 62 16. "Haida" temperature graphs, 1948 67 17. General circulation, illustrating "feed-backs" 74 18. Map of inner part of Disko bay 79 19. -

POL Volume 2 Issue 16 Back Matter

THE POLAR RECORD INDEX NUMBERS 9—16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN FOR THE SCOTT POLAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1939 THE POLAR RECORD INDEX Nos. 9-16 JANUARY 1935—JULY 1938 The names of ships are in italics. Expedition titles are listed separately at Uie end Aagaard, Bjarne, II. 112 Alazei Mountains, 15. 5 Abruzzi, Duke of, 15. 2 Alazei Plateau, 12. 125 Adams, Cdr. .1. B., 9. 72 Alazei River, 14. 95, 15. 6 Adams, M. B., 16. 71 Albert I Peninsula, 13. 22 Adderley, J. A., 16. 97 Albert Harbour, 14. 136 Adelaer, Cape, 11. 32 Alberta, 9. 50 Adelaide Island, 11. 99, 12. 102, 103, 13. Aldan, 11. 7 84, 14. 147 Aldinger, Dr H., 12. 138 Adelaide Peninsula, 14. 139 Alert, 11. 3 Admiralty Inlet, 13. 49, 14. 134, 15. 38 Aleutian Islands, 9. 40-47, 11. 71, 12. Advent Bay, 10. 81, 82, 11. 18, 13. 21, 128, 13. 52, 53, 14. 173, 15. 49, 16. 15. 4, 16. 79, 81 118 Adytcha, River, 14. 109 Aleutian Mountains, 13. 53 Aegyr, 13. 30 Alexander, Cape, 11. GO, 15. 40 Aerial Surveys, see Flights Alexander I Land, 12. 103, KM, 13. 85, Aerodrome Bay, II. 59 80, 14. 147, 1-19-152 Aeroplanes, 9. 20-30, 04, (i5-(>8, 10. 102, Alcxamtrov, —, 13. 13 II. 60, 75, 79, 101, 12. 15«, 158, 13. Alexcyev, A. D., 9. 15, 14. 102, 15. Ki, 88, 14. 142, 158-103, 16. 92, 93, 94, 16. 92,93, see also unilcr Flights Alftiimyri, 15. -

LUFF-THESIS-2019.Pdf (1.220Mb)

Sources of Variation in Mercury Levels in Arctic-breeding Shorebirds A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Department of Biology University of Saskatchewan By Katelyn Luff, B.Sc. © Copyright Katelyn Luff, May 2019. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Biology University of Saskatchewan 112 Science Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5E2 Canada Or Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon Saskatchewan S7N 5C9 Canada Recommended Citation: Luff, K M. -

Tab 008 RM001 2015 Mar 9 Summary of the 2015 Hydrographic Survey

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: X Decision: Issue: Summary of the 2015 Hydrographic Survey Plan for the Arctic. Background: It should be noted that the Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) conduct hydrographic surveys with the primary goal of updating official Government of Canada navigational products to the benefit of enhanced navigation safety. Data from hydrographic surveys has additional utility for those conducting everything from fisheries research, coastal zone management, to geo-hazards analysis. Here’s a summary of the CHS plans for the Arctic in 2015: 1) Western Arctic Survey Purpose: To collect modern bathymetry on an opportunity basis in Coronation Gulf, Queen Maud Gulf and Simpson Strait in order to facilitate enhanced navigational products to the benefit of vessels transiting this area. This work will be conducted while the Coast Guard are conducting their annual Aids Maintenance program. Platforms: Icebreaker CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier, CHS survey launches Kinglett and Gannett. Dates: August 5th to 28th, 2015. 2) Victoria Strait Survey Purpose: CHS will expand the modern hydrographic data coverage through Victoria Strait as a result of participating in a multi-departmental initiative led by Parks Canada whose aim is to locate the remaining lost vessel HMS Terror from the Franklin Expedition of 1846. All CHS data collected will be used to update or produce navigational publications. Note: The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) vessel may also be tasked to conduct hydrographic operations prior to or immediately after this survey in the northerly portion of Milne Inlet, Baffin Island. Platforms: Icebreaker CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier, CHS survey launches Kinglett and Gannett and a RCN vessel (Kingston Class), name to be determined.