LUFF-THESIS-2019.Pdf (1.220Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Special Management Measures for Midcontinent Lesser Snow Geese and Ross’S Geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group

Evaluation of special management measures for midcontinent lesser snow geese and ross’s geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group A Special Publication of the Arctic Goose Joint Venture of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan Evaluation of special management measures for midcontinent lesser snow geese and ross’s geese Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group A Special Publication of the Arctic Goose Joint Venture of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan Edited by: James O. Leafloor, Timothy J. Moser, and Bruce D.J. Batt Working Group Members James O. Leafloor Co-Chair Canadian Wildlife Service Timothy J. Moser Co-Chair U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bruce D. J. Batt Past Chair Ducks Unlimited, Inc. Kenneth F. Abraham Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Ray T. Alisauskas Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada F. Dale Caswell Canadian Wildlife Service Kevin W. Dufour Canadian Wildlife Service Michel H. Gendron Canadian Wildlife Service David A. Graber Missouri Department of Conservation Robert L. Jefferies University of Toronto Michael A. Johnson North Dakota Game and Fish Department Dana K. Kellett Wildlife Research Division, Environment Canada David N. Koons Utah State University Paul I. Padding U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Eric T. Reed Canadian Wildlife Service Robert F. Rockwell American Museum of Natural History Evaluation of Special Management Measures for Midcontinent Snow Geese and Ross's Geese: Report of the Arctic Goose Habitat Working Group SUGGESTED citations: Abraham, K. F., R. L. Jefferies, R. T. Alisauskas, and R. F. Rockwell. 2012. Northern wetland ecosystems and their response to high densities of lesser snow geese and Ross’s geese. -

Proceedings Template

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2020/032 Central and Arctic Region Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area in support of the identification of an Area of Interest T.N. Loewen1, C.A. Hornby1, M. Johnson2, C. Chambers2, K. Dawson2, D. MacDonell2, W. Bernhardt2, R. Gnanapragasam2, M. Pierrejean4 and E. Choy3 1Freshwater Institute Fisheries and Oceans Canada 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 2North/South Consulting Ltd. 83 Scurfield Blvd, Winnipeg, MB R3Y 1G4 3McGill University. 845 Sherbrooke Rue, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4 4Laval University Pavillon Alexandre-Vachon 1045, , av. of Medicine Quebec City, QC G1V 0A6 July 2020 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2020 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Loewen, T. N., Hornby, C.A., Johnson, M., Chambers, C., Dawson, K., MacDonell, D., Bernhardt, W., Gnanapragasam, R., Pierrejean, M., and Choy, E. 2020. Ecological and Biophysical Overview of the Southampton proposed Area of Interest for the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. -

![QAQSAUQTUUQ MIGRATORY BIRD SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN [January 2020] Acknowledgements](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4894/qaqsauqtuuq-migratory-bird-sanctuary-management-plan-january-2020-acknowledgements-1324894.webp)

QAQSAUQTUUQ MIGRATORY BIRD SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN [January 2020] Acknowledgements

QAQSAUQTUUQ MIGRATORY BIRD SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN [January 2020] Acknowledgements: Current and former members of the Irniurviit Area Co-management Committee (Irniurviit ACMC) developed the following management plan. Members are: Noah Kadlak, Kevin Angootealuk, Jean-Francois Dufour, Willie Adams, Annie Ningeongan, Louisa Kudluk, Armand Angootealuk, Darryl Nakoolak, Willie Eetuk, and Randy Kataluk. Chris Grosset (Aarluk Consulting Ltd.) and Kim Klaczek prepared the outline, document inventory and early drafts. Susan M. Stephenson (CWS) and Kevin J. McCormick (CWS) drafted an earlier version of the management plan in 1986. Ron Ningeongan (Kivalliq Inuit Association, Community Liaison Officer) and Cindy Ningeongan (Interpreter) contributed to the success of the establishment and operation of the Irniurviit ACMC. Suzie Napayok (Tusaajiit Translations) translated into Inuktitut all ACMC documents leading to and including this management plan. Jim Leafloor (CWS), Paul Smith (ECCC), and Grant Gilchrist (ECCC) contributed information and expert review throughout the management planning process. The Irniurviit ACMC and CWS also wish to thank the community of Coral Harbour and all the organizations and people who reviewed this document at any part of the management planning process. Copies of this Plan are available at the following addresses: Environment and Climate Change Canada Public inquiries centre Fontaine Building 12th floor 200 Sacré-Coeur Blvd Gatineau, QC. K1A 0H3 Telephone: 819-938-3860 Toll-free: 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) Email: [email protected] Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service Northern Region 3rd Floor, 933 Mivvik Street PO Box 1870 Iqaluit, NU. X0A 0H0 Telephone: 867-975-4642 Environment and Climate Change Canada Protected Areas website: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/national-wildlife-areas.html ISBN: [to be provided for final version only] Cat. -

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

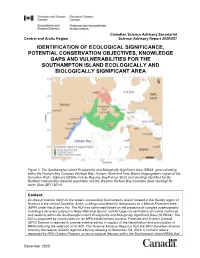

Identification of Ecological Significance, Potential

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Central and Arctic Region Science Advisory Report 2020/057 IDENTIFICATION OF ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE, POTENTIAL CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES, KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND VULNERABILITIES FOR THE SOUTHAMPTON ISLAND ECOLOGICALLY AND BIOLOGICALLY SIGNIFICANT AREA Figure 1. The Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA; green shading) within the Hudson Bay Complex (Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait and Foxe Basin) biogeographic region of the Canadian Arctic. Adjacent EBSAs include Repulse Bay/Frozen Strait (red shading) identified for the Northern Hudson Bay Narwhal population and the Western Hudson Bay Coastline (blue shading) for Arctic Char (DFO 2011). Context: An Area of Interest (AOI) for the waters surrounding Southampton Island, located in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut in the central Canadian Arctic, is being considered for designation as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) under the Oceans Act. The AOI was nominated based on the presence of complex oceanography, including a recurrent polynya in Roes Welcome Sound, and for large concentrations of marine mammals and seabirds within the Southampton Island Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (SI EBSA). The AOI is supported by communities for an MPA establishment process. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Science is required to provide science advice in support of the identification and prioritization of MPAs following the selection of an AOI. This Science Advisory Report is from the DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) regional advisory meeting of December 5-6, 2018. It contains advice requested by DFO Oceans Program on key ecological features within the Southampton Island EBSA that December 2020 Southampton Island AOI Ecological Central and Arctic Region Significance and potential COs warrant marine protection and recommends conservation objectives. -

THE HUDSON BAY, JAMES BAY and FOXE BASIN MARINE ECOSYSTEM: a Review

THE HUDSON BAY, JAMES BAY AND FOXE BASIN MARINE ECOSYSTEM: A Review Agata Durkalec and Kaitlin Breton Honeyman, Eds. Polynya Consulting Group Prepared for Oceans North June, 2021 The Hudson Bay, James Bay and Foxe Basin Marine Ecosystem: A Review Prepared for Oceans North by Polynya Consulting Group Editors: Agata Durkalec, Kaitlin Breton Honeyman, Jennie Knopp and Maude Durand Chapter authors: Chapter 1: Editorial team Chapter 2: Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 3: Kaitlin Wilson, Agata Durkalec Chapter 4: Charity Justrabo, Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 5: Agata Durkalec, Hilary Warne Chapter 6: Agata Durkalec, Kaitlin Wilson, Kaitlin Breton-Honeyman, Hilary Warne Cover photo: Umiujaq, Nunavik (photo credit Agata Durkalec) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Approach ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 GEOGRAPHICAL BOUNDARIES ........................................................................................................................... -

Distribution and Migration of the Bowhead Whale, Balaena Mysticetus, in the Eastern North American Arctic

ARCTIC VOL. 36, NO. 1 (MARCH lW)P. 5-64 Distribution and Migration of the Bowhead Whale, Baluenu mysticetus, in the Eastern North American Arctic RANDALL REEVES,’ EDWARD MITCHELL,’ ARTHUR MANSFIELD,’ and MICHELE MCLAUGHLIN’.~ ABSTRACT. Largecatches of bowhead whales, Bulaena mysficerus, were made in the Eastern Arctic of NorthAmerica, principally in Davis Strait, Baffin Bay, the Lancaster Sound region, Hudson Bay, and southern Foxe Basin, between 1719 and 1915. Initial stock sizes have been estimated as 1 I OOO in 1825 for the “Davis Strait stock” and 680 in 1859 for the “Hudson Bay stock.” The separate identity of these two putative stocks needs confirmation through direct evidence. Three sets of data were used to evaluate historic and present-day trends in the distribution of bowheads in the Eastern Arctic andto test hypotheses concerning the nature, timing, and routes of their migration. Published records from commercial whale fisheries prior to 1915, unpublished and some publishedrecords from the post-commercial whaling period 1915-1974, and reportedsightings made mainly by environmental assessment per- sonnel between 1975 and 1979, were tabulated and plotted on charts. Comments made by whalers and nineteenthcentury naturalists concerning bowhead distribution and movements were summarized and critically evaluated. The major whalinggrounds were: (1) the west coast of Greenland betweenca. 60”Nand 73”N, the spring and early summer “east side” grounds of the British whalers;(2) the spring “south-west fishing” grounds, including the northeast coast of Labrador, the mouth of Hudson Strait, southeast Baftin Island, and the pack ice edge extending east from Resolution Island; (3) the summer “west water” grounds, including Pond Inlet, the Lan- caster Sound region, and Prince Regent Inlet; (4) the autumn “rock-nosing” grounds along the entire east coast of Baffin Island; (5) Cumbedand Sound, a spring and fall ground; and (6)northwest Hudson Bay/southwest Foxe Basin. -

Hudson Bay Project Annual Report

THE HUDSON BAY PROJECT ECOSYSTEM STUDIES IN COASTAL ARCTIC TUNDRA 2015 PROGRESS REPORT The results presented in this report are preliminary and the interpretation is subject to change as more data become available. The information is being made available for the purpose of keeping our supporting agencies and sponsors, collaborating investigators, and other researchers informed of progress as of December 2015. Much of the material will be incorporated into publications as soon as analyses are complete. Suggested Citation: Hudson Bay Project. 2015. The Hudson Bay Project: 2015 Annual Progress Report. 78 pp. Table of Contents OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................... 9 SEASONAL PHENOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 10 LA PÉROUSE BAY AND CAPE CHURCHILL REGION, MANITOBA ...................................................................... 10 Ice and Weather .................................................................................................................................. 10 AKIMISKI ISLAND, NUNAVUT, AND THE ONTARIO COASTS OF JAMES BAY AND HUDSON BAY ........................... 13 Phenology ........................................................................................................................................... 13 VEGETATION AND HABITAT RESEARCH ............................................................................................. -

Ff Ff F F F Ff F F F F F F Ff F F Ff F F F F F F F F F Ff F F F F Ff

130°0'0"W 120°0'0"W 110°0'0"W 100°0'0"W 90°0'0"WF F 80°0'0"W GREENLAND FF Hudson U.S.A. F Bay Resolute Quebec Area 1 ! Qikiqtani ound r S as te Nunavut, Canada LFanc Sanikiluaq Figure 4.3-2 F! Char Species - CANADA Area 2 F Kitikmeot Arctic Char Range2 U.S.A. Arctic Char Area of Abundance2 Area of Detail ! F 4 F! Arctic Bay Lake Trout Range Traditional Harvest Data 1,3 F Arctic Char James Commercia Ontario Bay F F M F Commercial/Domestic ' C Area 2 F Domestic l F i n Sport t F F o F 1,3 Lake Trout c F k Domestic 70°0'0"N F C h Base Features a Qikiqtani n n ! Community e F l F F F Road F Conservation Area F Lake / River Nunavut Regional Boundary National Park F Migratory Bird Sanctuary F 70°0'0"N National Wildlife Area F F F Gulf F of F F ! F FF 1:5,000,000 Boothia F Tal oyo ak F F F! 2512.5 0 25 50 75 100 125 Cambridge Bay ! F F! F F FF FF Kilometres F F Prepared By: Nunami-Stantec F! F Kugluktuk F GjoaF Haven F! F! F F References: F F F Kugaaruk F! 1Canadian Circumpolar Institute. 1992. Nunavut Atlas. In R. Riewe (ed.), F Canadian Circumpolar Institute and the Tungavik Federation of Nunavut. F Umingmaktok Edmonton, AB. F 2 F Mercier, F., F. Rennie, D. Harvey and C.A. -

Habitat Change at a Multi-Species Goose Breeding Area on Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada, 1979–2010

TSPACE RESEARCH REPOSITORY tspace.library.utoronto.ca OPEN ACCESS Version: Version of Record with supplementary materials 2020 Habitat change at a multi-species goose breeding area on Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada, 1979–2010 Kenneth F. Abraham, Christopher M. Sharp, and Peter M. Kotanen Tis version of record is licensed under Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). To view the details of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Visit Publisher’s Site for the VoR: https://doi.org/10.1139/as-2018-0032 95 ARTICLE Habitat change at a multi-species goose breeding area on Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada, 1979–2010 Kenneth F. Abraham, Christopher M. Sharp, and Peter M. Kotanen Abstract: Foraging by hyperabundant Arctic-nesting geese has significant impacts on vegetation of Arctic and subarctic coastal lowlands, but long-term data sets documenting these changes are rare. We undertook intensive surveys of plant communities at East Bay and South Bay, Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada, in July 2010. Lesser Snow Geese, Ross’s Geese, Cackling Geese, and Brant nest and rear young at these sites; the first three have experienced up to 10-fold increases since the 1970s. At East Bay, we found significant declines in graminoids over the 31-year span, as well as significant declines in lichen and willow cover, and significant increases in rock cover. Transect data indicated graminoids were present at only 15%–36% of points at East Bay, whereas at South Bay, graminoids were present at 28%–90% of points. Moss was more prominent in transects at South Bay than at East Bay (40%–85% vs. -

Sailing Directions Pictograph Legend

Fisheries and Oceans Pêches et Océans Canada Canada Corrected to Monthly Edition No. 06/2020 ARC 400 FIRST EDITION General Information Northern Canada Sailing Directions Pictograph legend Anchorage ARC ARC 403 402 Wharf Marina ARC 404 Current ARC 401 Caution Light Radio calling-in point Lifesaving station Pilotage Government of Canada Information line 1-613-993-0999 Canadian Coast Guard Search and Rescue Joint Rescue Coordination Centre Trenton (Great Lakes and Arctic) 1-800-267-7270 Cover photograph Ellesmere Island, near Fort Conger Photo by: David Adler, [email protected] B O O K L E T A R C 4 0 0 Corrected to Monthly Edition No. 06/2020 Sailing Directions General Information Northern Canada First Edition 2009 Fisheries and Oceans Canada Users of this publication are requested to forward information regarding newly discovered dangers, changes in aids to navigation, the existence of new shoals or channels, printing errors, or other information that would be useful for the correction of nautical charts and hydrographic publications affecting Canadian waters to: Director General Canadian Hydrographic Service Fisheries and Oceans Canada Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1A 0E6 The Canadian Hydrographic Service produces and distributes Nautical Charts, Sailing Directions, Small Craft Guides, Canadian Tide and Current Tables and the Atlas of Tidal Currents of the navigable waters of Canada. These publications are available from authorized Canadian Hydrographic Service Chart Dealers. For information about these publications, please contact: Canadian Hydrographic Service Fisheries and Oceans Canada 200 Kent Street Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1A 0E6 Phone: 613-998-4931 Toll Free: 1-866-546-3613 Fax: 613-998-1217 E-mail: [email protected] or visit the CHS web site for dealer location and related information at: www.charts.gc.ca © Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2009 Catalogue No. -

Consolidation of Wildlife Regions Regulations

WILDLIFE ACT LOI SUR LA FAUNE CONSOLIDATION OF WILDLIFE CODIFICATION ADMINISTRATIVE REGIONS REGULATIONS DU R-108-98 RÈGLEMENT SUR LES RÉGIONS FAUNIQUES R-108-98 AS AMENDED BY MODIFIÉ PAR This consolidation is not an official statement of the La presénte codification administrative ne constitue law. It is an office consolidation prepared for pas le texte officiel de la loi; elle n’est établie qu'à convenience of reference only. The authoritative text titre documentaire. Seuls les règlements contenus of regulations can be ascertained from the Revised dans les Règlements révisés des Territoires du Nord- Regulations of the Northwest Territories, 1990 and Ouest (1990) et dans les parutions mensuelles de la the monthly publication of Part II of the Northwest Partie II de la Gazette des Territoires du Nord-Ouest Territories Gazette (for regulations made before (dans le cas des règlements pris avant le 1er avril April 1, 1999) and Part II of the Nunavut Gazette (for 1999) et de la Partie II de la Gazette du Nunavut regulations made on or after April 1, 1999). (dans le cas des règlements pris depuis le 1 er avril 1999) ont force de loi. WILDLIFE ACT LOI SUR LA FAUNE WILDLIFE REGIONS RÈGLEMENT SUR LES RÉGIONS REGULATIONS FAUNIQUES The Commissioner, on the recommendation of Le commissaire, sur la recommendation du the Minister, under section 98 of the Wildlife Act and ministre, en vertu de l’article 98 de la Loi sur la every enabling power, makes the Wildlife Regions faune et de tout pouvoir habilitant, prend le Regulations. Règlement sur les régions fauniques.