Encounters with the Neighbour in 1970S' British Multicultural Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kelsale-Cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-Mail: [email protected]

Kelsale-cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-mail: [email protected] www.kelsalecarltonpc.org.uk MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL PARISH MEETING HELD ON WEDNESDAY 17th April 2019 IN KELSALE VILLAGE HALL AT 7:00PM __________________________________________________________________________ Present: Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) & Elizabeth Flight – Parish Clerk. Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) welcomed members of the public and representatives and formally opened the meeting. Public Forum 1. To receive Apologies for Absence. Apologies were accepted from – Cllr Burslem (away), Cllr Martin Lumb, Jenni Aird, Auriol and Michael Marson 2. Approval of the draft minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. The Chairman made a note that last year’s minutes had been available recently on the website and village noticeboards to read before approval. The minutes were taken as read and proposed by Cllr Galloway for approval by seconded by Cllr Buttle. A vote was taken where they were agreed, and they were duly signed by the Chairman as a true record of the meeting. 3. Matters Arising from the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. There were none. The Chairman thanked Cllr Roberts for organising tonight’s presentation. Cllr Roberts announced that a film called Town Settlement would be shown. Cllr Roberts who had source the film gave a brief introduction and explanation of the film before it was shown. Cllr Roberts also announced that there is a competition – if anyone can recognise 10 things in the film to let them know after the meeting. INTERVAL (15 Minutes) – Very enjoyable light refreshments were served – thank you to all those who assisted in organising these. -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side. -

SMA 1991.Pdf

C 614 5. ,(-7-1.4" SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 21, 1991 CONTENTS Page Spring Conference 1991 1 Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 39 Northamptonshire 58 Ox-fordshire 79 Index 124 EDITOR: Andrew Pike CHAIRMAN: Dr Richard Ivens Bucks County Museum Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Technical Centre, Tring Road, 16 Erica Road Halton, Aylesbury, HP22 5PJ Stacey Bushes Milton Keynes MX12 6PA HON SEC: Stephen Coleman TREASURER: Barry Home County Planning Dept, 'Beaumont', Bedfordshire County Council Church End, County Hall, Edlesborough, Bedford. Dunstable, Beds. MX42 9AP LU6 2EP Typeset by Barry Home Printed by Central Printing Section, Bucks County Council ISSN 0960-7552 CBA South Midlands The two major events of CBA IX's year were the AGM and Spring Conference, both of which were very successful. CHAIRMAN'S LETTER Last year's A.G.M. hosted the Beatrice de Cardi lecture and the speaker, Derek Riley, gave a lucid account of his Turning back through past issues of our journal I find a pioneering work in the field of aerial archaeology. CBA's recurrent editorial theme is the parlous financial state of President, Professor Rosemary Cramp, and Director, Henry CBA IX and the likelihood that SMA would have to cease Cleere also attended. As many of you will know Henry publication. Previous corrunittees battled on and continued Cleere retires this year so I would like to take this to produce this valuable series. It is therefore gratifying to opportunity of wishing him well for the future and to thank note that SMA has been singled out as a model example in him for his many years of service. -

Don Warrington W1D 6LD

www.cam.co.uk Email [email protected] Address Don 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue London Warrington W1D 6LD Telephone +44 (0) 20 7292 0600 Television Title Role Director Production THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GRANDPA Grandpa Alexander James Jacob Milkshake! DEATH IN PARADISE- All series produced Selwyn Patterson Various BBC THE FIVE Ray Kenwood Mark Tonderai Sky THE ARK Paul Red Productions BBC CHASING SHADOWS CS Drayton Jim O'Hanlon ITV LAW AND ORDER Callaghan Andy Goddard ITV LEWIS Prof Woolf David O'Neill ITV THIS IS JINSY Chief Thinker Matt Lipsey BBC WAKING THE DEAD Adam Barclay Tim Fywell BBC GOING POSTAL Priest Jon Jones SKY CASUALTY Trevor- Semi Regular Various BBC LAW & ORDER Chief Commissioner Andy Goddard ITV COMET Futureshock Keith Boak Channel 5/ Darlow Smithson NEW STREET LAW Judge Ken Winyard Various BBC/Red Productions DIAMOND GEEZER Hector Paul Harrision YTV ALL STAR COMEDY SHOW - David Evans ITV THE CROUCHES Bailey Nick Wood BBC TO PLAY THE KING Graham Gaunt Paul Seed BBC ARABIAN KNIGHTS Hari Ben Karim Steve Barron Hallmark Productions CATS EYES Nigel Beaumont Various TVS MAN CHILD Patrick Various BBC THE ARMAND IANNUCCI Ivy Diner Channel 4 Talkback TRAIL & TRIBUTION Willard Pembroke Various ITV RISING DAMP Philip Smith Various ITV Theatre Title Role Director Production DEATH OF A SALESMAN Willy Loman Sarah Frankcom Royal Exchange GLENGARRY GLEN ROSS George Aaronow Sam Yates Playhouse Theatre KING LEAR King Lear Michael Buffong Talawa Theatre Company ALL MY SONS Joe Keller Michael Buffong Manchester Royal Exchange DRIVING MISS -

Dialects of London East End and Their Representation in the Media

Vanja Kavgić Dialects of London East End and their representation in the media. Cockney dialect and Multicultural London English in British sitcoms. MASTER THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Programme: Master's programme English and American Studies Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexander Onysko Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, June 2018 Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic thesis is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this thesis to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Vanja Kavgic e.h. Klagenfurt, 28.06.2018 1 Table of Contents AKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................... -

DIRECT DEMOCRACY: an Agenda for a New Model Party

29505_J Norman_NMP 7/6/05 13:35 Page C DIRECT DEMOCRACY: An Agenda for a New Model Party direct-democracy.co.uk 29505_J Norman_NMP 7/6/05 13:35 Page D First published 2005 Copyright © 2005 The Authors We actively encourage the reproduction of this book's ideas, particularly by ministers and civil servants. Published by direct-democracy.co.uk A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-9550598-0-1 Typeset and printed by Impress Print Services Ltd, London 29505_J Norman_NMP 7/6/05 13:35 Page E Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: The Tory Collapse 7 Chapter Two: The Rise of Anti-Politics 21 Chapter Three: Command Politics 34 Chapter Four: Direct Democracy 44 ILocal Government 46 II Crime 54 III Education 65 IV Health 74 VConstitutional Reform 81 VI New Model Party 96 A Note on the Authors 101 29505_J Norman_NMP 7/6/05 13:35 Page F "All decisions are delegated by politicians, because politicians don't want to take responsibility for them, to quangoes, and quangoes aren't answerable to anybody. Now what can you really hold a politician responsible for in domestic policy?" Lord Butler of Brockwell, Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Home Civil Service 1988–1998 December 2004 "It may be that the era of pure representative democracy is slowly coming to an end." Peter Mandelson, European Commissioner March 1998 29505_J Norman_NMP 7/6/05 13:35 Page 1 INTRODUCTION So it goes on. Once again, the Conservative Party is starting a new parliament with fewer MPs than Labour enjoyed in 1983, its popularity declining in important areas of our country, its future insecure. -

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!”

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!” Dr. Laurence Clark, North West Disability Arts Forum (Paper presented at the ‘Finding the Spotlight’ Conference, Liverpool Institute for the Performing Arts, 30th May 2003) Abstract Traditionally comedy involving disabled people has extracted humour from people’s impairments – i.e. a “functional limitation”. Examples range from Shakespeare’s ‘fool’ character and Elizabethan joke books to characters in modern TV sitcoms. Common arguments for the use of such disempowering portrayals are that “nothing is meant by them” and that “people should be able to laugh at themselves”. This paper looks at the effects of such ‘disabling comedy’. These include the damage done to the general public’s perceptions of disabled people, the contribution to the erosion of a disabled people’s ‘identity’ and how accepting disablist comedy as the ‘norm’ has served to exclude disabled writers / comedians / performers from the profession. 1. Introduction Society has been deriving humour from disabled people for centuries. Elizabethan joke books were full of jokes about disabled people with a variety of impairments. During the 17th and 18th centuries, keeping 'idiots' as objects of humour was common among those who had the money to do so, and visits to Bedlam and other 'mental' institutions were a typical form of entertainment (Barnes, 1992, page 14). Bilken and Bogdana (1977) identified “the disabled person as an object of ridicule” as one of the ten media stereotypes of disabled people. Apart from ridicule, disabled people have been largely excluded from the world of comedy in the past. For example, in the eighties American stand-up comedian George Carlin was arrested whilst doing his act for swearing in front of young disabled people. -

1 © 2013 Yougov Ltd. All Rights Reserved Yougov.Co.Uk Liberal

Liberal Democrat rank Have I Got News for You 1 Mock the Week 2 QI 3 Black Books 4 The IT Crowd 5 Brass Eye 6 Doctor Who 7 Red Dwarf 8 Futurama 9 Newswipe with Charlie Brooker 10 Family Guy 11 Russell Howard's Good News 12 Pride and Prejudice 13 Sherlock 14 The Thick of It 15 Being Human 16 Wallace and Gromit 17 Grand Designs 18 Elementary 19 Bremner, Bird and Fortune 20 8 Out of 10 Cats 21 Just a Minute 22 Blackadder 23 The Big Bang Theory 24 Fry's Planet Word 25 Jeeves and Wooster 26 Spaced 27 Dexter 28 Castle 29 The Armando Iannucci Shows 30 House of Cards 31 Green Wing 32 Firefly 33 That Mitchell And Webb Look 34 Buffy the Vampire Slayer 35 Parks and Recreation 36 Brainiac 37 Whose Line Is It Anyway? 38 Time Team 39 Tomorrow's World 40 Scrubs 41 Peep Show 42 Knowing Me, Knowing You... with Alan Partridge 43 BBC News 44 Campus 45 The Golden Age of Canals 46 That Was The Week That Was 47 Charlie Brooker's Screenwipe 48 1 © 2013 YouGov Ltd. All Rights Reserved yougov.co.uk Liberal Democrat rank Look Around You 49 Stand Up for the Week 50 Arrested Development 51 Dirk Gently 52 Stingray 53 The Sunday Night Project 54 Would I Lie To You? 55 Psychoville 56 The Big Fat Quiz of the Year 57 Wonders of the Universe 58 South Park 59 Vicious 60 Watson & Oliver 61 Dead Ringers 62 Absolutely Fabulous 63 Extreme Makeover 64 True Blood 65 Jack Dee Live at the Apollo 66 Nigella Bites 67 Planet Earth 68 Hancock's Half Hour 69 Friends 70 Putin, Russia and the West 71 How the Earth Was Made 72 Kath & Kim 73 Changing Rooms 74 My So-Called Life 75 Click 76 Ask Rhod Gilbert 77 Vic Reeves Big Night Out 78 Batman 79 How Clean is Your House? 80 Goodness Gracious Me 81 Supernatural 82 Walking with Dinosaurs 83 American Dad! 84 The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy 85 The Day Today 86 Not the Nine O'Clock News 87 Argumental 88 Is It Bill Bailey? 89 Russell Howard Live 90 Acorn Antiques 91 The Impressions Show with Culshaw and Stephenson 92 My Hero 93 The Office 94 House 95 New Girl 96 The Returned 97 Big Train 98 Due South 99 Destination Titan 100 2 © 2013 YouGov Ltd. -

A State of Play: British Politics on Screen, Stage and Page, from Anthony Trollope To

Fielding, Steven. "Imagining the Post-War Consensus." A State of Play: British Politics on Screen, Stage and Page, from Anthony Trollope to . : Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 107–130. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472545015.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 09:32 UTC. Copyright © Steven Fielding 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Imagining the Post-War Consensus Many now look on the two decades immediately following the end of the Second World War as marking the zenith of Britain’s two-party system.1 The interwar coalitions, party splits and minority governments were no more, while Labour and the Conservatives enjoyed unprecedented support. At the 1950 general election eighty-four per cent of the electorate voted and of this number ninety-seven per cent chose one or other of the two parties who claimed to have a combined total of three million members. At this point Labour and the Conservatives appeared to hold a secure place in the people’s affections: as the political scientist Robert McKenzie concluded in 1955, they were ‘two great monolithic structures’ deeply embedded in society.2 More broadly, leading social scientists believed – encouraged by many Britons’ effusive reaction to the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 – that the rulers and ruled enjoyed a ‘moral unity’.3 Most contemporaries also considered that the collectivist policies introduced by the 1945 Attlee government had solved Britain’s interwar economic problems. -

Onthefrontline

★ Paul Flynn ★ Seán Moncrieff ★ Roe McDermott ★ 7-day TV &Radio Saturday, April 25, 2020 MES TI SH IRI MATHE GAZINE On the front line Aday inside St Vincent’s Hospital Ticket INSIDE nthe last few weeks, the peopleof rear-viewmirror, there was nothing samey Ireland could feasibly be brokeninto or oppressivelyboring or pedestrian about Inside two factions:the haves and the suburban Dublinatall. Come to think of it, have-nots.Nope, nothing to do with the whys and wherefores of the estate I Ichildren, or holiday homes, or even grew up on were absolutely bewitching.As employment.Instead, I’m talking gardens. kids, we’d duck in and out of each other’s How I’ve enviedmysocialmediafriends houses: ahuge,boisterous,fluid tribe. with their lush, landscaped gardens, or Friends would stay for dinner if there were COLUMNISTS their functionalpatio furniture, or even enough Findus Crispy Pancakes to go 4 SeánMoncrieff their small paddling pools.AnInstagram round.Sometimes –and Idon’tknow how 6 Ross photo of someone enjoying sundownersin or why we ever did this –myfriends and I O’Carroll-Kelly their own back gardenisenough to tip me would swap bedrooms for the night,sothat 17 RoeMcDermott over the edge. Honestly, Icould never have they would be sleeping in my house and Iin 20 LauraKennedy foreseen ascenario in whichI’d look at theirs. Perhaps we fancied ourselvesas someone’smodest back garden and feel characters in our own high-concept, COVERSTORY genuine envy (and, as an interesting body-swap story.Yet no one’s parents 8 chaser, guilt for worrying aboutgardens seemed to mind. -

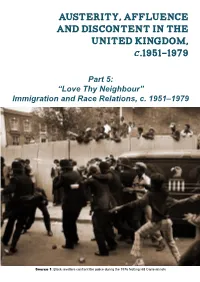

Austerity, Affluence and Discontent in the United Kingdom, .1951-1979

AUSTERITY, AFFLUENCE AND DISCONTENT IN THE UNITED KINGDOM, .1951-1979 Part 5: “Love Thy Neighbour” Immigration and Race Relations, c. 1951–1979 Source 1: Black revellers confront the police during the 1976 Notting Hill Carnival riots 2 Austerity, Affluence and Discontent in the United Kingdom, c.1951–1979: Part 5 Introduction Before the Second World War there were very few non-white people living permanently in the UK, but there were 2 million by 1971. Two thirds of them had come from the Commonwealth countries of the West Indies, India, Pakistan and Hong Kong, but one third had been born in the UK. The Commonwealth was the name given to the countries of the British Empire. However, as more and more countries became independent from the UK, the Commonwealth came to mean countries that had once been part of the Empire. Immigration was not new. By the 1940s there were already black communities in port cities like Bootle in Liverpool and Tiger Bay in Cardiff. Groups of Chinese people had come to live in the UK at the end of the 19th century and had settled in Limehouse in London, and in the Chinatown in Liverpool. Black West Indians had come to the UK to fight in the Second World War. The RAF had Jamaica and Trinidad squadrons and the Army had a West Indian regiment. As a result there were 30,000 non-white people in the UK by the end of the war.1 The British people had also been very welcoming to the 130,000 African-American troops of the US Army stationed in the UK during the war. -

4 October 2019 Page 1 of 9

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 28 September – 4 October 2019 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 28 SEPTEMBER 2019 series.Producer: Beaty RubensFirst broadcast on BBC Radio 4 consequences for all except himself and his leader.For years his in March 2014. family have tried to get hold of the stoker's diaries, for they SAT 00:00 Daphne du Maurier - The Blue Lenses SAT 02:30 Dave Sheasby - Shifting the Leaves (b007jtch) believe his account of the epic journey should be worth a (b007k4rp) Episode 5 fortune. It turns out to be a revelation.Robin Bailey stars as Episode 2 In her quest to finally come to terms with her Cornish past, Stoker Leishman in Peter Tinniswood's drama.Frederick Afer discovering she's able to see things that others can't, Marda Marjorie gets help from some youngsters.Written by Dave Leishman ....Robin BaileyMrs Bentall ... Shirley DixonDora .... West fears for her survival in this dangerous new world.The Sheasby.Marjorie Beaumont ...... Elizabeth Bradley.Mrs Nugent Barbara MartenGordon .... Christian RodskaBarbara .... Liz conclusion of Daphne du Maurier's two-part fantasy thriller ...... June BarrieMandy ...... Alison PettittTilson ...... Tristan GouldingEdgar ... Martin MatthewsDirector: Tony Cliff.First exploring the darker aspects of human nature.Read by Emma SturrockProducer: David HunterFirst broadcast on BBC Radio broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in January 1981. Fielding.Produced and abridged by Gemma Jenkins.Made for 4 in April 1998. SAT 07:30 Mabey in the Wild (b02qd1s3) BBC 7 and first broadcast in 2007. SAT 02:45 Ricky Tomlinson - Ricky (m0008r28) Series 2 SAT 00:30 Off the Page (b0076mw8) Episode 5 Yew, Sycamore And Ash Boredom Concluding his autobiography, actor Ricky Tomlinson recalls In the first of two programmes about British trees, Richard Matthew Parris and his guests are inspired by boredom.