SMA 1991.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kelsale-Cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-Mail: [email protected]

Kelsale-cum-Carlton Parish Council 31 Kings Road, Leiston, Suffolk, IP16 4DA Tel: 07733 355657, E-mail: [email protected] www.kelsalecarltonpc.org.uk MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL PARISH MEETING HELD ON WEDNESDAY 17th April 2019 IN KELSALE VILLAGE HALL AT 7:00PM __________________________________________________________________________ Present: Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) & Elizabeth Flight – Parish Clerk. Cllr Alan Revell (Chairman) welcomed members of the public and representatives and formally opened the meeting. Public Forum 1. To receive Apologies for Absence. Apologies were accepted from – Cllr Burslem (away), Cllr Martin Lumb, Jenni Aird, Auriol and Michael Marson 2. Approval of the draft minutes of the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. The Chairman made a note that last year’s minutes had been available recently on the website and village noticeboards to read before approval. The minutes were taken as read and proposed by Cllr Galloway for approval by seconded by Cllr Buttle. A vote was taken where they were agreed, and they were duly signed by the Chairman as a true record of the meeting. 3. Matters Arising from the Annual Parish Meeting held on 18th April 2018. There were none. The Chairman thanked Cllr Roberts for organising tonight’s presentation. Cllr Roberts announced that a film called Town Settlement would be shown. Cllr Roberts who had source the film gave a brief introduction and explanation of the film before it was shown. Cllr Roberts also announced that there is a competition – if anyone can recognise 10 things in the film to let them know after the meeting. INTERVAL (15 Minutes) – Very enjoyable light refreshments were served – thank you to all those who assisted in organising these. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

Dear Mr Griffiths Freedom of Information Request Further to Your

Mr G Griffiths request-261315- Our ref: FOI2258 2014-15MJ [email protected] Date: 28 April 2015 Dear Mr Griffiths Freedom of Information Request Further to your request received on 31 March 2015, please see Central Bedfordshire Council’s response to your questions below: Q1. How you request your DBS Checks currently? Paper or Online? A1. DBS checks are currently requested in paper form. Q2. Do you use a third party or request them direct with the DBS? A2. We request DBS checks directly. Q3. If you use a third party, which company is it? When did you start using them? How much do you pay per Enhanced Disclosure? Is the provider decided by a tender process, if not who is the individual within the council that makes the decision? A3. We do not use a third party provider. Q4. How many DBS checks did you request between 1st Jan 14 – 31st Dec 14? A4. We requested 1,485 DBS checks between 1st Jan – 31st Dec 2014. Q5. Do you provide an umbrella body service to organisations? A5. We do provide an umbrella service to other organisations. Q6. If so, please can you list the names of the organisations. Please include a primary contact name and telephone. A6. Please see the table below: Central Bedfordshire Council Please reply to: Telephone 0300 300 8301 Access to Information Team Email [email protected] Central Bedfordshire Council www.centralbedfordshire.gov.uk Priory House, Monks Walk, Chicksands, Shefford, Bedfordshire SG17 5TQ Co/org/team/sch Address Tel No Email ool name 11 North Parade Greyfriars 24-7 Cars 01234 511247 Bedford MK40 1JF 113a Midland Road Mrs Jan - 07861 jan_3starcars@btinternet 3 Star Cars Bedford 667588 .com MK40 1DA 01234 333333 Three Star (Luton) Ltd Unit 1 3 star coaches Guardian Business Park Dallow Rd Luton LU1 1 26 Bedford Square, 69ers Dunstable, LU5 5ES 01582 696969 Waz 07540 696969 27a Tavistock Street [email protected]. -

Luton Motor Town

Contents Luton: Motor Town Luton: Motor Town 1910 - 2000 The resources in this pack focus on the major changes in the town during the 20th century. For the majority of the period Luton was a prosperous, optimistic town that encouraged forward-looking local planning and policy. The Straw Hat Boom Town, seeing problems ahead in its dependence on a single industry, worked hard to attract and develop new industries. In doing so it fuelled a growth that changed the town forever. However Luton became almost as dependant on the motor industry as it had been on the hat industry. The aim of this pack is to provide a core of resources that will help pupils studying local history at KS2 and 3 form a picture of Luton at this time. The primary evidence included in this pack may photocopied for educational use. If you wish to reproduce any part of this park for any other purpose then you should first contact Luton Museum Service for permission. Please remember these sheets are for educational use only. Normal copyright protection applies. Contents 1: Teachers’ Notes Suggestions for using these resources Bibliography 2: The Town and its buildings 20th Century Descriptions A collection of references to the town from a variety of sources. They illustrate how the town has been viewed by others during this period. Luton Council on Luton The following are quotes from the Year Book and Official Guides produced by Luton Council over the years. They offer an idea of how the Luton Council saw the town it was running. -

All Saints' Newsletter

ALL SAINTS’ NEWSLETTER Issue 9 ‐ Thursday 30th June 2016 Leadership and Management service and community. I hope that more of our students will take up the opportunity to experience the A Message from the Chair of Governors Award Scheme in the coming years. Dear Parents and Carers This will be my final newsleer contribuon for this academic year. Our students and staff have all worked The dreadful events in Orlando and Birstall recently have very hard and I am sure they are all looking forward to highlighted the hatred that some members of society a well‐earned rest over the summer period. I hope the feel towards each other. Thankfully, we live in a world weather is a lile more generous than it has been in where there is far more good than evil, although recent months. I do parcularly want to thank all the somemes the news seems to suggest staff for the contribuon they have made this year and otherwise. Pung aside any polical agenda, the values parcularly to Liz Furber and her Senior Leadership that were used to describe the approach of Jo Cox MP Team who took over the Academy at a very difficult seem to be ones that could be applied to any, and all, me and have set about their task with real walks of life, parcularly within a place like our own determinaon. Thanks also to my colleague governors Academy. Those values, arculated by the Prime and the two Sponsors who connue to provide me with Minister in paying tribute to Jo Cox, are: Service, tremendous encouragement and the value of their Community and Tolerance. -

South Bedfordshire Intergroup Meetings

South Bedfordshire Intergroup Meetings Leighton Buzzard Chaired Online Harlington Open Sunday Luton Stopsley Big Book Monday Sunday Harlington Parish Rooms, Church Rd Wigmore Church & Community Centre, Crawley Green Crombie House, 36 Hockliffe St Time: 19.00 - duration 1hr Rd, Stopsley, No refreshments available, please bring Time: 19.30 - duration 1hr 30mins Postcode: LU5 6LE your own Postcode: LU7 1HJ UID: 3089 Hand sanitiser available UID: 107 This physical meeting has opened up again Please wear face coverings Social distancing seating Time: 19.00 - duration 1hr 30mins Postcode: LU2 9TE UID: 108 This physical meeting has opened up again Luton Tuesday Leighton Buzzard Newcomers Leighton Buzzard Big Book Strathmore Avenue Methodist church, 43 Strathmore Online Tuesday Tuesday Ave Crombie House, 36 Hockliffe St Astral Park Community Centre, Johnson Drive, Time: 13.00 - duration 1hr Time: 20.00 - duration 1hr Postcode: LU1 3NZ Postcode: LU7 1HJ Time: 20.00 - duration 1hr UID: 6805 UID: 5215 Postcode: LU7 4AY This physical meeting has opened up again UID: 5951 This physical meeting has opened up again Dunstable 12 Step Recovery Luton Lewsey Farm Wednesday Leighton Buzzard Newcomers Online Tuesday St Hugh's Church, Leagrave High St Wednesday United Reformed Church Hall, Edward St Time: 20.00 - duration 1hr The Salvation Army, Lamass Walk, Visitors need to Time: 20.00 - duration 1hr Postcode: LU4 0ND contact us on email: Postcode: LU6 1HE UID: 5923 [email protected] if UID: 102 This physical meeting has opened up again -

Houghton Conquest Circular Walk 1

Houghton Conquest Circular Walk 1 Introduction Placed centrally in Bedfordshire and lying at the foot of the Greensand Ridge at the crossing of two ancient roads, the village takes its name from the coupling of the old English "hoh" and "tun” (meaning a farmstead on or near a ridge or hill-spur) with the name of an important local family in the c13th - the Conquests. This attractive circular route crosses meadows and woodland and passes near Houghton House., thought to be “The House Beautiful” in John Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress.” Detours may be taken to Kings Wood, an ancient woodland, and Glebe Meadows, a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Houghton Conquest can be reached by road from the A6 (Bedford –Luton) or from the B530 (Bedford – Ampthill) roads. Parking is available in the Village Hall car park but may be limited if other functions or events are taking place there. On- street parking in available elsewhere in the village. Please park thoughtfully. There is an hourly bus service from Bedford (Route 42). Start/Finish Point The walk starts from the Knife and Cleaver public house opposite the Village Church. (OS Grid TL043414) Access and General Information Length: 3 miles (4.8km) Time: 2 hours Surface Types: The walk goes across varied surfaces ranging from a hard, firm surface to grass or uncultivated earth paths. Please note that this route can become very muddy in winter or in wet weather. Refreshments: There are two pubs in Houghton Conquest - The Knife and Cleaver and The Anchor. There is a shop near to the village hall. -

The Stockwood Park Academy Admission Arrangements 2019-2020

The Stockwood Park Academy Admission Arrangements 2019-2020 Title: Admissions Policy 2019-20 Reviewed by: The Board of Trustees Approved: February 2018 Review date: Autumn 2019 1 Background to The Stockwood Park Academy The Stockwood Park Academy is part of The Shared Learning Trust, which currently also comprises The Chalk Hills Academy, The Linden Academy and The Vale Academy. The Stockwood Park Academy is a co-educational, mixed-ability secondary school for children aged 11-18, situated within Luton Borough Council, located at its site on Rotherham Avenue, Luton. The agreed admission number is 300 for the Year 7 intake in 2019-2020. Admissions to The Stockwood Park Academy for 2019-2020 Section 324 of the Education Act 1996 requires the governing bodies of all maintained schools and academies to admit a child with a statement of special educational needs that names their school. Schools must also admit children with an EHC (Educational Health and Care) plan that names the school. The Stockwood Park Academy Admission arrangements 2019-2020 shall apply to applications made in the Academic year 2018/19 onwards, for admission to The Stockwood Park Academy in the Academic year 2019- 2020. For Year 7 applicants within the normal admissions round, applications for The Stockwood Park Academy for September 2019 onwards will be in accordance with the Luton Borough Council coordinated admissions arrangements and will be made on the common application form provided and administered by Luton Borough Council. Where numbers of applications for year 7, or other year groups, exceed the published admission numbers the following oversubscription rules will apply in consecutive order: Over subscription criteria Rule 1. -

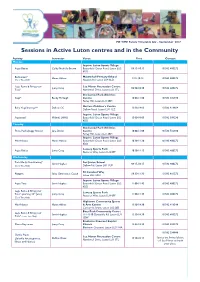

Sessions in Active Luton Centres and in the Community

ME TIME Family Timetable July – September 2017 Sessions in Active Luton centres and in the Community Activity Instructor Venue Time Contact Monday Inspire: Luton Sports Village Aqua Babies Colby Nicholls-Brown Butterfield Green Road, Luton LU2 09:15-10:15 01582 400272 8DD Maidenhall Primary School Badminton* Huma Abbasi 9:15-10:15 01582 400272 (Term Time Only) Newark Rd, Luton LU4 8LD Legs, Bums & Bring your Lea Manor Recreation Centre Jenny Crisp 09:30-10:30 01582 400272 Tots* Northwell Drive, Luton LU3 3TL Stockwood Park Athletics Yoga* Becky McVeigh Centre 10:00-11:00 01582 722930 Farley Hill, Luton LU1 4BH Hatters Children’s Centre Baby Yoga/massage** Dallow CC 13:00-14:00 01582 616604 Dallow Road, Luton LU1 1LZ Inspire: Luton Sports Village Aquanatal Midwife (NHS) Butterfield Green Road, Luton LU2 15:00-16:00 01582 393230 8DD Tuesday Stockwood Park Athletics Fit to Push (buggy fitness) Jane Dixon Centre 10:00-11:00 01582 722930 Farley Hill, Luton LU1 4BH Inspire: Luton Sports Village Mini-Nastics Huma Abbasi Butterfield Green Road, Luton LU2 10:30-11:30 01582 400272 8DD Lewsey Sports Park Aqua Babies Jenny Crisp 10:30-11:15 01582 400272 Pastures Way, Luton LU4 0PF Wednesday Total Body Conditioning* Fox Junior School Sarah Hughes 09:15-10:15 01582 400272 (Term Time Only) Dallow Rd, Luton LU1 1UP 98 Camford Way Playgym Salto Gymnastics Coach 09:30-11:30 01582 400272 Luton LU3 3AN Inspire: Luton Sports Village Aqua Totz Sarah Hughes Butterfield Green Road, Luton LU2 11:00-11:45 01582 400272 8DD Legs, Bums & Bring your Lewsey Sports -

Compendium of World War Two Memories

World War Two memories Short accounts of the wartime experiences of individual Radley residents and memories of life on the home front in the village Compiled by Christine Wootton Published on the Club website in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War Two Party to celebrate VJ Day in August 1946 Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day) was on 8 August 1945. It's likely the party shown in the photograph above was held in Lower Radley in a field next to the railway line opposite the old village hall. Club member Rita Ford remembers a party held there with the little ones in fancy dress, including Winston Churchill and wife, a soldier and a Spitfire. The photograph fits this description. It's possible the party was one of a series held after 1945 until well into the 1950s to celebrate VE Day and similar events, and so the date of 1946 handwritten on the photograph may indeed be correct. www.radleyhistoryclub.org.uk ABOUT THE PROJECT These accounts prepared by Club member and past chairman, Christine Wootton, have two main sources: • recordings from Radley History Club’s extensive oral history collection • material acquired by Christine during research on other topics. Below Christine explains how the project came about. Some years ago Radley resident, Bill Small, gave a talk at the Radley Retirement Group about his time as a prisoner of war. He was captured in May 1940 at Dunkirk and the 80th anniversary reminded me that I had a transcript of his talk. I felt that it would be good to share his experiences with the wider community and this set me off thinking that it would be useful to record, in an easily accessible form, the wartime experiences of more Radley people. -

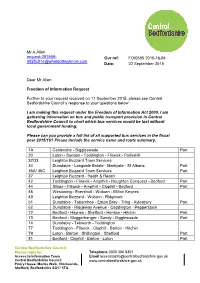

Dear Mr Allen Freedom of Information Request Further to Your Request

Mr A Allen request-291569- Our ref: FOI0595 2015-16JM [email protected] Date: 22 September 2015 Dear Mr Allen Freedom of Information Request Further to your request received on 11 September 2015, please see Central Bedfordshire Council’s response to your questions below: I am making this request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. I am gathering information on bus and public transport provision in Central Bedfordshire Council to chart which bus services would be lost without local government funding. Please can you provide a full list of all supported bus services in the fiscal year 2015/16? Please include the service name and route summary. 1A Caldecotte - Biggleswade Part 20 Luton - Sundon - Toddington - Flitwick - Pulloxhill 32/33 Leighton Buzzard Town Services 34 Dunstable - Langdale Estate - Markyate - St Albans Part 36A/ 36C Leighton Buzzard Town Services Part 37 Leighton Buzzard - Heath & Reach 42 Toddington - Flitwick - Ampthill - Houghton Conquest - Bedford Part 44 Silsoe - Flitwick - Ampthill - Clophill - Bedford Part 48 Westoning - Eversholt - Woburn - Milton Keynes 49 Leighton Buzzard - Woburn - Ridgmont 61 Dunstable - Totternhoe - Eaton Bray - Tring - Aylesbury Part 62 Dunstable - Ridgeway Avenue - Caddington - Pepperstock 72 Bedford - Haynes - Shefford - Henlow - Hitchin Part 73 Bedford - Moggerhanger - Sandy - Biggleswade Part 74 Dunstable - Tebworth - Toddington 77 Toddington - Flitwick - Clophill - Barton - Hitchin 79 Luton - Barton - Shillington - Shefford Part 81 Bedford - Clophill - Barton - Luton -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side.