Information 123

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Diocesan News

Diocesan News December 2019 www.leeds.anglican.org Christmas calls Diocesan Bishop Nick Baines Secretary Advent is here and Christmas beckons. It doesn’t seem announces so long ago that we were working out how to tell the retirement Christmas story afresh, and now we have to do it again. Debbie Child, Diocesan Is there anything new to so do we today long for a Secretary for the Diocese of say? I guess the answer is resolution of our problems Leeds, is to retire from her post ‘no’ – even if we might find and struggles. But, in a funny on 31 March 2020. new ways to say the same old sort of way, Christmas offers thing. Christmas opens up for an answer that the question us, after a month of waiting of Advent did not expect. and preparing to be surprised, God did not come among us to wonder again about God, on a war horse. God didn’t the world and ourselves. If wipe out the contradictions the story has become stale, and sufferings in a single it is not the fault of the sweep of power. Rather, story, but a problem with God finds himself born in a our imagination. The birth feeding trough at the back of Jesus sees God entering of the house – subject to all Debbie has served the Diocese the real human experiences the diseases, violence and of Bradford and, latterly, Leeds and dilemmas that we face dangers any baby faced in that since 1991. as we seek to live faithfully place and at that time. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

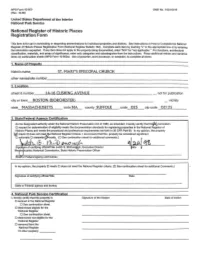

Applicable." for Functions, Architectural Classification, Materials, and Areas of Significance, Enter Only Categories and Subcategories from the Instructions

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form Is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name._---'-___--=s'-'-T~ • .:....M::...A=R~Y_"S~EP=_=I=SC=O=_'_'PA:....:..=.L~C:.:..H~U=R=C=H..!.._ ______________ other names/site number___________________________________ _ 2. Location city or town_-=.B=O-=.ST..:...O=..:...,:N:.....J(..::;D-=O:...,:.R.=C=.H.:.=E=ST..:...E=R.=) ________________ _ vicinity state MASSACHUSETTS code MA county SUFFOLK code 025 zip code 02125 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that thi~ nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Royal Gold Medall

1912 - Basil Champneys 1977 - Sir Denys Lasdun Royal Gold Medall 1913 - Sir Reginald Blomfield 1978 - Jørn Utzon 1914 - Jean Louis Pascal 1979 - Charles and Ray Eames 1848 - Charles Robert Cockerell 1915 - Frank Darling, Canada 1980 - James Stirling 1849 - Luigi Canina 1916 - Sir Robert Rowand Anderson 1981 - Sir Philip Dowson 1850 - Sir Charles Barry 1917 - Henri Paul Nenot 1982 - Berthold Lubetkin 1851 - Thomas Leverton Donaldson 1918 - Ernest Newton 1983 - Sir Norman Foster 1852 - Leo von Klenze 1919 - Leonard Stokes 1984 - Charles Correa 1853 - Sir Robert Smirke 1920 - Charles Louis Girault 1985 - Sir Richard Rogers 1854 - Philip Hardwick 1921 - Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens 1986 - Arata Isozaki 1855 - Jacques Ignace Hittorff 1922 - Thomas Hastings 1987 - Ralph Erskine 1856 - Sir William Tite 1923 - Sir John James Burnet 1988 - Richard Meier 1857 - Owen Jones 1924 - No award 1989 - Renzo Piano 1858 - Friedrich August Stüler 1925 - Sir Giles Gilbert Scott 1990 - Aldo van Eyck 1859 - Sir George Gilbert Scott 1926 - Prof. Ragnar Ostberg 1991 - Colin Stansfield Smith 1860 - Sydney Smirke 1927 - Sir Herbert Baker 1992 - Peter Rice 1861 - JB Lesueur 1928 - Sir Guy Dawber 1993 - Giancarlo de Carlo 1862 - Rev Robert Willis 1929 - Victor Alexandre Frederic 1994 - Michael and Patricia Hopkins 1863 - Anthony Salvin Laloux 1995 - Colin Rowe 1864 - Eugene Viollet-le-Duc 1930 - Percy Scott Worthington 1996 - Harry Seidler 1865 - Sir James Pennethorne 1931 - Sir Edwin Cooper 1997 - Tadao Ando 1866 - Sir Matthew Digby Wyatt 1932 - Dr. Hendrik Petrus Berlage 1998 - Oscar Niemeyer 1867 - Charles Texier 1933 - Sir Charles Reed Peers 1999 - Barcelona 1868 - Sir Austen Henry Layard 1934 - Henry Vaughan Lanchester 2000 - Frank Gehry 1869 - Karl Richard Lepsius 1935 - Willem Marinus Dudok 2001 - Jean Nouvel 1870 - Benjamin Ferrey 1936 - Charles Henry Holden 2002 - Archigram 1871 - James Fergusson 1937 - Sir Raymond Unwin 2003 - Rafael Moneo 1872 - Baron von Schmidt 1938 - Prof. -

SMA 1991.Pdf

C 614 5. ,(-7-1.4" SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 21, 1991 CONTENTS Page Spring Conference 1991 1 Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 39 Northamptonshire 58 Ox-fordshire 79 Index 124 EDITOR: Andrew Pike CHAIRMAN: Dr Richard Ivens Bucks County Museum Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Technical Centre, Tring Road, 16 Erica Road Halton, Aylesbury, HP22 5PJ Stacey Bushes Milton Keynes MX12 6PA HON SEC: Stephen Coleman TREASURER: Barry Home County Planning Dept, 'Beaumont', Bedfordshire County Council Church End, County Hall, Edlesborough, Bedford. Dunstable, Beds. MX42 9AP LU6 2EP Typeset by Barry Home Printed by Central Printing Section, Bucks County Council ISSN 0960-7552 CBA South Midlands The two major events of CBA IX's year were the AGM and Spring Conference, both of which were very successful. CHAIRMAN'S LETTER Last year's A.G.M. hosted the Beatrice de Cardi lecture and the speaker, Derek Riley, gave a lucid account of his Turning back through past issues of our journal I find a pioneering work in the field of aerial archaeology. CBA's recurrent editorial theme is the parlous financial state of President, Professor Rosemary Cramp, and Director, Henry CBA IX and the likelihood that SMA would have to cease Cleere also attended. As many of you will know Henry publication. Previous corrunittees battled on and continued Cleere retires this year so I would like to take this to produce this valuable series. It is therefore gratifying to opportunity of wishing him well for the future and to thank note that SMA has been singled out as a model example in him for his many years of service. -

1 the Stones of Science: Charles Harriot Smith and the Importance of Geology in Architecture, 1834-1864 in the Stones of Venice

1 The Stones of Science: Charles Harriot Smith and the importance of geology in architecture, 1834-1864 In The Stones of Venice England’s leading art critic, John Ruskin (1819-1900), made explicit the importance of geological knowledge for architecture. Clearly an architect’s choice of stone was central to the character of a building, but Ruskin used the composition of rock to help define the nature of the Gothic style. He invoked a powerful geological analogy which he believed would have resonance with his readers, explaining how the Gothic character could be submitted to analysis, ‘just as the rough mineral is submitted to that of the chemist’. Like geological minerals, Ruskin asserted that the Gothic was not pure, but composed of several elements. Elaborating on this chemical analogy, he observed that, ‘in defining a mineral by its constituent parts, it is not one nor another of them, that can make up the mineral, but the union of all: for instance, it is neither in charcoal, nor in oxygen, nor in lime, that there is the making of chalk, but in the combination of all three’.1 Ruskin concluded that the same was true for the Gothic; the style was a union of specific elements, such as naturalism (the love of nature) and grotesqueness (the use of disturbing imagination).2 Ruskin’s analogy between moral elements in architecture and chemical elements in geology was not just rhetorical. His choice to use geology in connection with architecture was part of a growing consensus that the two disciplines were fundamentally linked. In early-Victorian Britain, the study of geology invoked radically new ways of conceptualizing the earth’s history. -

The Franciscans in Hertfordshire. a Note in Commemoration : 1224—1924

The Franciscans in Hertfordshire. A Note in Commemoration : 1224—1924. BY GERALD R. OWST, M.A., PH.D. "IN the year of the Lord 1224, in the time of the Lord Pope Honorius, in the same year, that is, in which the Rule of the blessed Francis was by him con- firmed, and in the eighth year of the Lord King Henry, son of John, on the Tuesday after the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, which that year fell upon a Sunday, the Friars Minor first arrived in England, land- ing at Dover. They were four clerics and five lay- brethren."1 Thus opens brother Thomas of Eccleston's narrative " Of the coming of the Friars Minor [or Franciscans] into England,' compiled probably about forty years after that first landing. At recent celebrations of the seventh hundred anniversary of the event, Eccles- ton's picturesque account of the heroic pioneers pressing on to Canterbury, from thence to London, and so even- tually to Oxford and other important towns, has been re-told. There is no need to linger, therefore, about those first guest-houses on the road, around the school- house fire at Canterbury, or the kitchen fire at Salisbury, where ill-fed and weary friars made merry over the wretched beer-dregs, or in the little cells erected in Corn- hill with their lining of dried grass. When did the brethren first reach Hertfordshire in days of extreme poverty, simplicity and holy joy? We do not know. Something more than mere chance would seem to have marked out St. -

Brief Histories of Churches Cardiff

Brief Histories of Churches in the Roath, Splott, Adamsdown, Cathays, Tremorfa, Tredegarville & Penylan areas of Cardiff Roath Local History Society in Cardiff has as its area of interest the old Parish of Roath in the 1880s. This covered not just the area we know as Roath today but also Splott, Adamsdown, Pengam, Pen-y-lan, and part of Cathays. This brief histories of churches looks at the churches that would have been in the area of old parish of Roath but also strays into neighbouring area such as Tredegarville and Cathays as a whole. There may be more churches to be included such as some mission halls that doubled up both as Sunday Schools as well as a church. A couple of synagogues are also included. Building of other faiths will be added over time, though some are already listed as former church buildings now house other faiths. Some errors and omissions in the details are likely. When the author is made aware of any errors, or additional information comes to light, the details on the website version will be updated where possible. The website also contains an interactive map that pinpoints the individual churches. Research for this compilation has relied heavily on a number of publications by members of Roath Local History Society in particular: ‘Cardiff Churches Through Time’ by Jean Rose. ‘Roath, Splott and Adamsdown, One Thousand Years of History’ by Jeff Childs. ‘Roath, Splott and Adamsdown – the Archive Photographs Series’ by Jeff Childs The author would also like to thank members of the various churches listed for their assistance and individuals of other organisations. -

KJ MASTER THESIS FINAL Corrections

Ordered Spaces, Separate Spheres: Women and the Building of British Convents, 1829-1939 Kate Jordan University College London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy I, Kate Jordan confirm that the work present- ed in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. _______________________________ Kate Jordan !2 Abstract Over the last forty years, feminist discourses have made considerable impact on the way that we understand women’s historical agency. Linda Nochlin’s question, ‘why have there been no great women artists’ challenged assumptions about the way we consider women in art history and Amanda Vickery brought to the fore questions of women’s authority within ‘separate spheres’ ideology. The paucity of research on women’s historical contributions to architecture, however, is a gap that misrepresents their significant roles. This thesis explores a hitherto overlooked group of buildings designed by and for women; nineteenth and twentieth century English convents. Many of these sites were built according to the rules of communities whose ministries extended beyond contemplative prayer and into the wider community, requiring spaces that allowed lay-women to live and work within the convent walls but without disrupting the real and imagined fabric of monastic traditions - spaces that were able to synthesise contemporary domestic, industrial and institutional architecture with the medieval cloister. The demanding specifications for these highly innovative and complex spaces were drawn up, overwhelmingly, by nuns. While convents might be read as spaces which operated at the interstices between different architectures, I will argue they were instead conceived as sites that per- formed varying and contradictory functions simultaneously. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Ecclesiology Today No.42

SEVEN CHURCH ARCHITECTS 1830 – 1930 Edited by Geoff Brandwood Ecclesiology Today . Issue 42 . June 2010 SEVEN CHURCH ARCHITECTS 1830 – 1930 SEVEN CHURCH ARCHITECTS 1830 – 1930 Edited by Geoff Brandwood Ecclesiology Today . Issue 42 . June 2010 © Copyright the authors 2010.All rights reserved. ISSN: 1460-4213 ISBN: 0 946823 24 3 Published 2010 by the Ecclesiological Society c/o The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House Piccadilly London WIV 0HS The Ecclesiological Society is a registered charity. Charity No. 210501. www.ecclsoc.org The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the Ecclesiological Society or its officers. Front cover: E. B. Lamb’s church of St Mary, Bagby, North Yorkshire, 1862. Rear cover:The crossing at Ewan Christian’s first church, St John’s, Hildenborough, Kent, 1843–4. Both photographs by Geoff Brandwood. Ecclesiology Today C ontents Journal of the Ecclesiological Society Chairman’s letter 2 Introduction by Geoff Brandwood 3 An alternative to Ecclesiology:William Wallen (1807-53) by Christopher Webster 9 The churches of E. B. Lamb: an exercise in centralised planning by Anthony Edwards 29 ‘The callous Mr Christian’: the making and unmaking of a professional reputation by Martin Cherry 49 ‘Inventive and ingenious’: designs by William White by Gill Hunter 69 ‘An architect of many churches’: John Pollard Seddon by Tye R. Blackshaw 83 George Fellowes Prynne (1853-1927): a dedicated life by Ruth Sharville 103 The ecclesiastical work of Hugh Thackeray Turner by Robin Stannard 121 Reviews 147 Issue 42 The Ecclesiological Society and submissions to published June 2010 Ecclesiology Today 163 Chairman’s letter This edition of Ecclesiology Today is devoted to seven very different church architects, whose work covers the period from late Georgian times to the first decades of the twentieth century.We are grateful to our guest editor, Dr Geoff Brandwood, for his vision and hard work in pulling together such an interesting edition.