KJ MASTER THESIS FINAL Corrections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760 Faridullah Bezhan on Gender and Autobiography Rosalind Carr on Scottish Women and Empire Nicola Cowmeadow on Scottish Noblewomen’s Political Activity in the 18th C Katie Barclay on Family Legacies Huw Clayton on Police Brutality Allegations Plus Five book reviews Call for Reviewers Prizes WHN Conference Reports Committee News www.womenshistorynetwork.org Women’s History Network 19th Annual Conference 2009 Performing the Self: Women’s Lives in Historical Perspective University of Warwick, 10-12 September 2010 Papers are invited for the 19th Annual Conference 2010 of the Women’s History Network. The idea that selfhood is performed has a very long tradition. This interdisciplinary conference will explore the diverse representations of women’s identities in the past and consider how these were articulated. Papers are particularly encouraged which focus upon the following: ■ Writing women’s histories ■ Gender and the politics of identity ■ Ritual and performance ■ The economics of selfhood: work and identity ■ Feminism and auto/biography ■ Performing arts ■ Teaching women’s history For more information please contact Dr Sarah Richardson: [email protected], Department of History, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL. Abstracts of papers (no more than 300 words) should be submitted to [email protected] The closing date for abstracts is 5th March 2010. Conference website: www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/res_rec/ conferences/whn Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the Autumn/Winter 2009 edition of reproduced in full. We plan to publish the Carol Adams WWomen’s History Magazine. -

JACKSON-THESIS-2016.Pdf (1.747Mb)

Copyright by Kody Sherman Jackson 2016 The Thesis Committee for Kody Sherman Jackson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Robert Abzug Virginia Garrard-Burnett Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal by Kody Sherman Jackson, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2016 Dedication To all those who helped in the publication of this work (especially Bob Abzug and Ginny Burnett), but most especially my brother. Just like my undergraduate thesis, it will be more interesting than anything you ever write. Abstract Jesus, Jung, and the Charismatics: The Pecos Benedictines and Visions of Religious Renewal Kody Sherman Jackson, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2016 Supervisor: Robert Abzug The Catholic Charismatic Renewal, though changing the face and feel of U.S. Catholicism, has received relatively little scholarly attention. Beginning in 1967 and peaking in the mid-1970s, the Renewal brought Pentecostal practices (speaking in tongues, faith healings, prophecy, etc.) into mainstream Catholicism. This thesis seeks to explore the Renewal on the national, regional, and individual level, with particular attention to lay and religious “covenant communities.” These groups of Catholics (and sometimes Protestants) devoted themselves to spreading Pentecostal practices amongst their brethren, sponsoring retreats, authoring pamphlets, and organizing conferences. -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

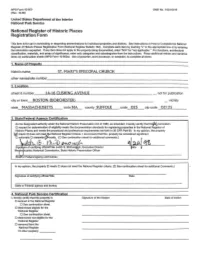

Applicable." for Functions, Architectural Classification, Materials, and Areas of Significance, Enter Only Categories and Subcategories from the Instructions

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form Is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name._---'-___--=s'-'-T~ • .:....M::...A=R~Y_"S~EP=_=I=SC=O=_'_'PA:....:..=.L~C:.:..H~U=R=C=H..!.._ ______________ other names/site number___________________________________ _ 2. Location city or town_-=.B=O-=.ST..:...O=..:...,:N:.....J(..::;D-=O:...,:.R.=C=.H.:.=E=ST..:...E=R.=) ________________ _ vicinity state MASSACHUSETTS code MA county SUFFOLK code 025 zip code 02125 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that thi~ nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Information 123

ISSN 0960-7870 BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY INFORMATION 123 FEBRUARY 2013 BRICK CHURCHES ISSUE OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY Chairman Michael Chapman 8 Pinfold Close Tel: 0115-965-2489 NOTTINGHAM NG14 6DP E-mail: [email protected] Honorary Secretary Michael S Oliver 19 Woodcroft Avenue Tel. 020-8954-4976 STANMORE E-mail: [email protected] Middlesex HA7 3PT Honorary Treasurer Graeme Perry 62 Carter Street Tel: 01889-566107 UTTOXETER E-mail: [email protected] Staffordshire ST14 8EU Enquiries Secretary Michael Hammett ARIBA 9 Bailey Close and Liason Officer with the BAA HIGH WYCOMBE Tel: 01494-520299 Buckinghamshire HP13 6QA E-mail: brick so c @mh 1936.plus. c om Membership Secretary Dr Anthony A. Preston 11 Harcourt Way (Receives all direct subscriptions, £12-00 per annum*) SELSEY, West Sussex P020 0PF Tel: 01243-607628 Editor of BBS Information David H. Kennett BA, MSc 7 Watery Lane (Receives all articles and items for BBS Information) SHIPSTON-ON-STOUR Tel: 01608-664039 Warwickshire CV36 4BE E-mail: [email protected] Printing and Distribution Chris Blanchett Holly Tree House, 18 Woodlands Road Secretary LITTLEHAMPTON Tel: 01903-717648 West Sussex BN17 5PP E-mail: [email protected] Web Officer Vacant The society's Auditor is: Adrian Corder-Birch F.Inst.L.Ex . Rustlings, Howe Drive E-mail: [email protected] HALSTEAD, Essex C09 2QL The annual subscription to the British Brick Society is £10-00 per annum. Telephone numbers and e-mail addresses of members would be helpful for contact purposes. but these will not be included in the Membership List. -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE OLIVETAN BENEDICTINES To The Most Reverend Father Michelangelo Riccardo M. Tiribilli Abbot General of the Olivetan Benedictine Congregation, 1. This year marks the 650th anniversary of the death of Bl. Bernard Tolomei, an impassioned “God-seeker” (cf. Benedictine Rule, 58:7), which this monastic congregation is joyfully preparing to celebrate. On this happy occasion, I am pleased to send you, Most Reverend Father, and the entire monastic congregation of the Olivetans my best wishes, while gladly joining in the common hymn of praise and thanksgiving to the Lord for the gift to his Church of such an important Gospel witness. By a providential coincidence, this anniversary falls in the second year of immediate preparation for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, the year dedicated to the Holy Spirit. The shining figure of Bl. Bernard, who established “schools of the Lord’s service” (cf. Benedictine Rule, Prol. 45), is a remarkable example of the presence and action of the Holy Spirit, the source of the great variety of charisms on which the Bride of Christ lives. In the heart of Bl. Bernard, “God’s love was poured out ... through the Holy Spirit” (cf. Rom 5:5) in abundance, and it thus made him a sign of the risen Lord. As a result, he was able to excel “in the life to which God has called him, for the increase of the holiness of the Church and for the greater glory of the one and undivided Trinity” (Dogm. Const. Lumen gentium, n. -

1 the Stones of Science: Charles Harriot Smith and the Importance of Geology in Architecture, 1834-1864 in the Stones of Venice

1 The Stones of Science: Charles Harriot Smith and the importance of geology in architecture, 1834-1864 In The Stones of Venice England’s leading art critic, John Ruskin (1819-1900), made explicit the importance of geological knowledge for architecture. Clearly an architect’s choice of stone was central to the character of a building, but Ruskin used the composition of rock to help define the nature of the Gothic style. He invoked a powerful geological analogy which he believed would have resonance with his readers, explaining how the Gothic character could be submitted to analysis, ‘just as the rough mineral is submitted to that of the chemist’. Like geological minerals, Ruskin asserted that the Gothic was not pure, but composed of several elements. Elaborating on this chemical analogy, he observed that, ‘in defining a mineral by its constituent parts, it is not one nor another of them, that can make up the mineral, but the union of all: for instance, it is neither in charcoal, nor in oxygen, nor in lime, that there is the making of chalk, but in the combination of all three’.1 Ruskin concluded that the same was true for the Gothic; the style was a union of specific elements, such as naturalism (the love of nature) and grotesqueness (the use of disturbing imagination).2 Ruskin’s analogy between moral elements in architecture and chemical elements in geology was not just rhetorical. His choice to use geology in connection with architecture was part of a growing consensus that the two disciplines were fundamentally linked. In early-Victorian Britain, the study of geology invoked radically new ways of conceptualizing the earth’s history. -

Midland Women, Developing Roles and Identitiesc.1760-1860Katrina Maitland-Brown MAA Thesis Submitted in Partia

Fulfilling Roles: Midland Women, developing roles and identities C.1760-1860 Katrina Maitland-Brown MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgments, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Katrina Maitland-Brown to be identified as the author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature……………………………. Date…………………………………. Abstract This thesis examines the lives of a group of Midland women in the period c. 1760- 1860. They were the wives, sisters, daughters and mothers of the middle-class entrepreneurial and professional men of the region. During this period the Midlands produced individuals who expanded production and commerce, often with little technical innovation, but with a shrewd sense of what was marketable. Men such as the Wedgwoods, Boultons and Kenricks built businesses, sponsored canals and highways, and invented, produced and sold an ever-expanding supply of goods world-wide. Yet while the lives of such men have been celebrated, the women of these families have often been overlooked. -

Popes in History

popes in history medals by Ľudmila Cvengrošová text by Mons . Viliam Judák Dear friends, Despite of having long-term experience in publishing in other areas, through the AXIS MEDIA company I have for the first time entered the environment of medal production. There have been several reasons for this decision. The topic going beyond the borders of not only Slovakia but the ones of Europe as well. The genuine work of the academic sculptress Ľudmila Cvengrošová, an admirable and nice artist. The fine text by the Bishop Viliam Judák. The “Popes in history” edition in this range is a unique work in the world. It proves our potential to offer a work eliminating borders through its mission. Literally and metaphorically, too. The fabulous processing of noble metals and miniatures produced with the smallest details possible will for sure attract the interest of antiquarians but also of those interested in this topic. Although this is a limited edition I am convinced that it will be provided to everybody who wants to commemorate significant part of the historical continuity and Christian civilization. I am pleased to have become part of this unique project, and I believe that whether the medals or this lovely book will present a good message on us in the world and on the world in us. Ján KOVÁČIK AXIS MEDIA 11 Celebrities grown in the artist’s hands There is one thing we always know for sure – that by having set a target for himself/herself an artist actually opens a wonderful world of invention and creativity. In the recent years the academic sculptress and medal maker Ľudmila Cvengrošová has devoted herself to marvellous group projects including a precious cycle of male and female monarchs of the House of Habsburg crowned at the St. -

Radical Politics and Domestic Life in Late-Georgian England, C.1790-1820

The Home-Making of the English Working Class: Radical Politics and Domestic Life in late-Georgian England, c.1790-1820. Ruth Mather Queen Mary, University of London. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2016. 1 Statement of originality. I, Ruth Mather, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 20th September, 2016. Details of collaboration and publications: R. Mather, ‘These Lancashire women are witches in politics’: Female reform societies and radical theatricality in the north-west of England, c.1819-20’ in Manchester Region History Review, Vol. 23 (2012), pp.49-64. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………… 4 Abstract ………………………………………………………………… 5 List of tables and figures ………………………………………………… 6 Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………… 9 Chapter 2: Imagining Home: Domestic Rhetoric, Gender and Political Radicalisms in England, c.1790-1820 ………………………………………………… 42 Chapter 3: The Politics of Making Home ………………………………… 69 Chapter 4: Power Relations: Family and Community in Popular Radicalism …. -

Chapel and Garden Heritage Walk

9. Statue of St. Michael 11. Chapel Nestled in the front gardens to your right is the The Loreto Chapel, or Children’s Chapel as it was known, statue of St. Michael. was built between 1898 and 1902. The architect was William Tappin and the builder, George Lorimer. It is built There is a Statue of St. Michael in every Loreto in an English Gothic style with French influence. The stone School. This tradition began in 1696, a time of is Barrabool Hills sandstone from near Geelong with white Catholic persecution in England. The Bar Convent in Oamaru, New Zealand, stone detailing. York was under attack. As a rioting mob approached the convent the Superior hung a picture of St. Building was interrupted through lack of funds but the Chapel and Garden Michael above the door to place the convent under project was finally completed with a large bequest from the his protection and the mob dispersed. German Countess Elizabeth Wolff-Metternich, who had been a student at the Convent in 1898. The Countess Heritage Walk 10. Front Building tragically died on a return visit to her family in Germany. Under the sandstone façade is the original house The inside of the Chapel is decorated in soft pastel colours purchased by the Loreto Sisters in 1875 to be a with artwork and statuary donated to the sisters by Ballarat school and convent. and Irish families. The Rose Window over the Organ Gallery The Regency style house was built for Edward Agar depicts St. Cecilia, patron saint of music, surrounded by Wynne in around 1868 as a family home. -

A Genealogy Researched & Compiled by Hugh Pitfield 2019

Pitfield A genealogy Researched & compiled by Hugh Pitfield 2019 [email protected] www.pitfield-family.co.uk Introduction In 1982 I thought it might be interesting to look into my family history. I started The Dorset Family out knowing very little apart from the fact that my father, and his father, came from The majority of the charts and notes in this volume relate to the Dorset family and Southampton in Hampshire. I quickly found that there were far more references to the show the known Pitfold/Pitfield descendants of Robert Pytfolde of Allington, Dorset name Pitfield in the county of Dorset than anywhere else, and I established that my (1516-1586). Details of the origins of this family are included in the Dorset Family own Southampton Pitfields originated in Dorset. Preface. Soon after starting on my genealogical quest I made contact with Michael Pitfield from Buckinghamshire who had already been doing some work on the Pitfield family. He Petfield, Peatfield, Patefield, Pilfield, Pilfold etc had established that most of the Pitfield lines are descended from a Robert Pitfold of There are a number of family names, in various parts of Britain, that sound similar Allington in Dorset who had ten sons and who died in 1586. Michael and I worked to Pitfield. Some of these names are well established and in some cases their use together for some years on the Pitfield lines and found that we were both descendants predates the name Pitfold, that later evolved into Pitfield. On occasion Pitfield might of Sebastian Pitfold, the youngest of Robert’s sons.