Compendium of World War Two Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

The Baldons and Nuneham Courtenay Newsletter September 2016

The Baldons and Nuneham Courtenay Newsletter Carfax Conduit, Nuneham Park – see inside for a rare opportunity to go on guided walks around the park and buildings! September 2016 FROM THE VICAR , REVD PAUL CAWTHORNE September is often a month full of delights. After our El Nino-affected climate over the winter and spring, we can wonder whether we will get a more normal autumn this year. Keats' season of mists and mellow fruitfulness feels such a lovely culmination of the yearly round, collecting apples, picking grapes from vines, basking in the sun's more gentle warmth, perhaps searching for mushrooms as they grow up through the moistening soil, I am sure we all have our favourite signs and activities of the season. It can be a time of relief for farmers as the vagaries of the weather seem less pressing once the grain is in the barn and the cattle are fat and full from summer grass, so there is a sense of moving to a less staccato pace again. For those of us who work less in contact with the soil, the rhythms are still there as we observe as much as partake. It has been intriguing this summer seeing friendly groups of teenagers out walking earnestly along the verges and round prominent buildings in our villages in a way which recalls the natural sociability and local exploration of previous years. If Pokémon Go has encouraged a new generation to look outwards more from the computer screen and game console, albeit through a phone screen, then that is presumably to be welcomed. -

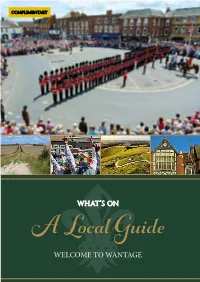

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1500–2000 by Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1500–2000 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The post-medieval rural landscape, c AD 1500–2000 By Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley INTRODUCTION Compared with previous periods, the study of the post-medieval rural landscape of the Thames Valley has received relatively little attention from archaeologists. Despite the increasing level of fieldwork and excavation across the region, there has been comparatively little synthesis, and the discourse remains tied to historical sources dominated by the Victoria County History series, the Agrarian History of England and Wales volumes, and more recently by the Historic County Atlases (see below). Nonetheless, the Thames Valley has a rich and distinctive regional character that developed tremendously from 1500 onwards. This chapter delves into these past 500 years to review the evidence for settlement and farming. It focusses on how the dominant medieval pattern of villages and open-field agriculture continued initially from the medieval period, through the dramatic changes brought about by Parliamentary enclosure and the Agricultural Revolution, and into the 20th century which witnessed new pressures from expanding urban centres, infrastructure and technology. THE PERIOD 1500–1650 by Anne Dodd Farmers As we have seen above, the late medieval period was one of adjustment to a new reality. -

Oxfordshire. Oxpo:Bd

DI:REOTO:BY I] OXFORDSHIRE. OXPO:BD. 199 Chilson-Hall, 1 Blue .Anchor,' sat Fawler-Millin, 1 White Hart,' sat Chilton, Berks-Webb, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Fawley, North & South-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, Chilton, Bucks-Shrimpton, ' Chequers,' wed. & sat. ; wed. & sat Wheeler 'Crown,' wed & sat Fencott--Cooper, ' White Hart,' wed. & sat Chilworth-Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat.; Honor, Fewcot-t Boddington, ' Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Shrimpton, 'Chequers,'wed.&sat Fingest--Croxford, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Chimney-Bryant, New inn, wed. & sat Finstock-:Millin, 'White Hart,' sat Chinnor-Croxford, 'Crown,' wed, & sat Forest Hill-White, 'White Hart,' mon. wed. fri. & sat. ; Chipping Hurst-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat Guns tone, New inn, wed. & sat Chipping Norton-Mrs. Eeles, 'Crown,' wed Frilford-Baseley, New inn, sat. ; Higgins, 'Crown,' Chipping Warden-Weston, 'Plough,' sat wed. & sat.; Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed. & sat Chiselhampton-Harding, 'Anchor,' New road, sat.; Fringford-Bourton, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Jones, 'Crown,' wed. & sat.; Moody, 'Clarendon,' sat Fritwell-Boddington, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Cholsey-Giles, ' Crown,' wed. & sat Fyfield-Broughton, 'Roebuck,' fri.; Stone, 'Anchor,' Cirencester-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat New road, sat.; Fisher, 'Anchor,' New road, fri Clanfield-Boucher, 'Blue Anchor,' wed. & sat Garford-Gaskin, 'Anchor,' New road, wed Claydon, East, Middle & Steeple-Bicester carriers Garsington-Howard, ' Crown,' mon. wed. & sat. ; Dover, Cleveley-Eeles, 'Crown,' sat New inn, mon. wed. fri. & sat.; Townsend, New inn, Clifton-by-Deddington-Boddington, 'Anchor,' wed. & mon. wed. •& sat sat.; Weston, 'Plough,' sat Glympton-Jones, 'Plough,' wed.; Humphries, 'Plough,' Clifton Hampden-Franklin, 'Chequers,' & 'Anchor,' sat New road, sat Golden Ball-Nuneham & Dorchester carriers Coate Bryant, New inn, wed. -

11 Nuneham Courtenay Oxford, Ox44 9Nx 11 Nuneham Courtenay Oxford, Ox44 9Nx

11 NUNEHAM COURTENAY OXFORD, OX44 9NX 11 NUNEHAM COURTENAY OXFORD, OX44 9NX Grade II Listed • Wealth of Period Features • Beautiful South & West Facing Garden • Off Road Parking • Large Beamed Sitting Room with Inglenook • Wood Burning Stove • Separate Fully Refurbished Annexe __________________________ DESCRIPTION A beautiful Grade II Listed property located c. six miles south of Oxford. The property has a wealth of period features and comprises three bedrooms, family bathroom, a large beamed sitting room with inglenook fire place, a study area, cloakroom, fully fitted kitchen with Rayburn stove, a separate utility room and fully refurbished annexe, comprising an open plan living area with kitchen, a bathroom, and a bedroom on the mezzanine floor, currently let successfully as an Airbnb. The attractive gardens are well stocked with parking for at least four cars. LOCATION Nuneham Courtenay is located 5 miles to the south east of central Oxford. The unique feature of the village is the two identical rows of period semi-detached properties facing each other. The village has Nuneham House with Thames-side frontage, and the Harcourt Arboretum. Access to the A34 is via the Oxford ring road and the A40/M40 can be accessed via the Green Road roundabout on the Eastern by-pass. Didcot railway station is approximately 8 miles providing fast links into London Paddington. Nearby Marsh Baldon has a well-regarded primary school, church and the popular 'Seven Stars' community owned public house. DIRECTIONS Leave Oxford via the A4074 towards Wallingford. Proceed along this road to the village of Nuneham Courtenay. Upon entering the village, take the first road halfway through the village on the right, signposted Global Retreat, take first left and the property is a little way down the lane on the left. -

Virtual Field Trip to Oxford

Resource 3: Virtual field trip to Oxford In this lesson you are going to take a virtual field trip to the area between Botley Road and New Hinksey in Oxford to see an example of a flood risk area. Some land uses are more badly affected by flooding than others. For example, it would be inconvenient if your school playing field was flooded it might be too wet to play on for a few days but no one would be hurt and no long-term damage would be done. However, it could be a disaster if a hospital was flooded. Patients would have to be moved and the lives of elderly or very sick people could be put at risk. It could take months and huge amounts of money to repair the damage to the building and equipment. For this reason, planners use flood plain zoning to prevent the construction of buildings on flood plains. The aim of your virtual fieldwork In your virtual field trip to Oxford you must identify the most common land uses that occur on the floodplain between Botley Road and New Hinksey. You could use enquiry questions to focus your investigation. For example: • What kinds of land uses are at risk of flooding in Oxford? • Which land uses will be protected by the new flood alleviation scheme? Alternatively, you could set yourself a hypothesis that can be tested. For example: • The Oxford Flood Alleviation Scheme is designed to protect the most valuable land uses. The method You are going to use photographic evidence to answer your enquiry questions or test your hypothesis. -

The 1522 Muster Role for West Berkshire (Part 5)

Vale and Downland Museum – Local History Series The 1522 Muster Role for West Berkshire (Part 5) - Incomes in Tudor Berkshire: A Recapitulation by Lis Garnish A well reasoned counter argument is always useful in research, calling for a reappraisal of the evidence and possibly opening up new and profitable lines of thought. Having written an initial article in "Oxfordshire Local History" on the 1522 Muster Certificate for west Berkshire (1), and a follow up one suggesting that the figures for “goods” were income rather than capital (2), I was pleased to see Simon Kemp’s article in reply (3). However, I finished reading the item with a sense of disappointment and confusion. Disappointment because he had produced very little in the way of extra evidence from the west Berkshire area, and confusion because he seemed to be countering propositions which I had not made. Kemp's article seems to contain two main lines of argument. Firstly, that the figures for “goods” given in the 1522 Muster Certificate were for “total wealth”, not income, and secondly that the comparison I made with later probate inventories was unjustified. If he had confined himself to the second argument he might have had a valid point. The comparison was a speculative one in an attempt to set the figures in a wider context, although in the absence of other hard evidence I feel it was justifiable to try to draw some conclusions. However, his case for “goods” being capital, as opposed to income, does not seem to have been made. Kemp's first criticism seems to be that two lists were required from the Muster Commissioners, that these were to be separate and that I have ignored this evidence (3). -

SMA 1991.Pdf

C 614 5. ,(-7-1.4" SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 21, 1991 CONTENTS Page Spring Conference 1991 1 Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 39 Northamptonshire 58 Ox-fordshire 79 Index 124 EDITOR: Andrew Pike CHAIRMAN: Dr Richard Ivens Bucks County Museum Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Technical Centre, Tring Road, 16 Erica Road Halton, Aylesbury, HP22 5PJ Stacey Bushes Milton Keynes MX12 6PA HON SEC: Stephen Coleman TREASURER: Barry Home County Planning Dept, 'Beaumont', Bedfordshire County Council Church End, County Hall, Edlesborough, Bedford. Dunstable, Beds. MX42 9AP LU6 2EP Typeset by Barry Home Printed by Central Printing Section, Bucks County Council ISSN 0960-7552 CBA South Midlands The two major events of CBA IX's year were the AGM and Spring Conference, both of which were very successful. CHAIRMAN'S LETTER Last year's A.G.M. hosted the Beatrice de Cardi lecture and the speaker, Derek Riley, gave a lucid account of his Turning back through past issues of our journal I find a pioneering work in the field of aerial archaeology. CBA's recurrent editorial theme is the parlous financial state of President, Professor Rosemary Cramp, and Director, Henry CBA IX and the likelihood that SMA would have to cease Cleere also attended. As many of you will know Henry publication. Previous corrunittees battled on and continued Cleere retires this year so I would like to take this to produce this valuable series. It is therefore gratifying to opportunity of wishing him well for the future and to thank note that SMA has been singled out as a model example in him for his many years of service. -

PARTING SHOTS and FAREWELL SALUTES ANNING the Salient Defences, Which Were So Exposed, So Close T O Those of the Enemy, Was Stil

CHAPTER 9 PARTING SHOTS AND FAREWELL SALUTES ANNING the Salient defences, which were so exposed, so close t o M those of the enemy, was still the most dangerous infantry duty to b e performed day by day in Tobruk . The diarist of the 2/13th Field Com- pany paid a special tribute to the 2/24th Battalion's work in the Salien t in re-siting the tactical wire to obtain maximum advantage from its fir e plan, which it did first on the left of the Salient (from 18th August t o 1st September) and later on the right (from 8th to 25th September) . In both sectors the 2/24th lost a number of men from anti-personnel mines . Nevertheless the Salient was less dangerous than in the summer month s because the defences had been gradually improved by deepening an d more overhead cover had been provided. Also the front-line troops of each side had developed a certain amount of tolerance of the other an d had unofficially adopted "live-and-let-live" attitudes to some extent . After sundown there was an unofficial truce for three or four hours, mor e strictly observed, it would appear, on the right of the Salient than on the left, during which both sides brought up their evening meal and undertook tasks on the surface (for example, repairs to wire) that were dangerou s at other times. The end of the nightly truce was usually notified by a flare-signal. There was a curious entry in the diary of the Italian officer captured o n the night on which Jack was overrun . -

NS8 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

NS8 bus time schedule & line map NS8 Oxford - Wantage View In Website Mode The NS8 bus line (Oxford - Wantage) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oxford City Centre: 12:55 AM - 1:55 AM (2) Wantage: 12:00 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest NS8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next NS8 bus arriving. Direction: Oxford City Centre NS8 bus Time Schedule 46 stops Oxford City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:55 AM - 1:55 AM Monday Not Operational Market Place, Wantage Church Street, Wantage Tuesday Not Operational Fitzwaryn School, Wantage Wednesday Not Operational 53 Denchworth Road, Wantage Civil Parish Thursday Not Operational Whittington Crescent, Wantage Friday Not Operational 97 Denchworth Road, Grove Civil Parish Saturday 12:55 AM - 1:55 AM Grove Airƒeld Memorial, Grove Cane Lane, Grove Cane Lane, Grove Civil Parish NS8 bus Info Wessex Way, Grove Direction: Oxford City Centre Stops: 46 Evenlode Close, Grove Trip Duration: 45 min Brunel Crescent, Grove Civil Parish Line Summary: Market Place, Wantage, Fitzwaryn School, Wantage, Whittington Crescent, Wantage, Collett Way, Grove Grove Airƒeld Memorial, Grove, Cane Lane, Grove, Wessex Way, Grove, Evenlode Close, Grove, Collett Wick Green, Grove Way, Grove, Wick Green, Grove, The Green, Grove, Mayƒeld Avenue, Grove, Williamsf1 Roundabout, The Green, Grove Grove, The Mulberries, East Hanney, The Black Horse, East Hanney, St James View, East Hanney, Ashƒelds Mayƒeld Avenue, Grove Lane, East Hanney, South Oxfordshire Crematorium,