Global Security in Crisis T H E U R G E N T N E E D for Strategies That Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

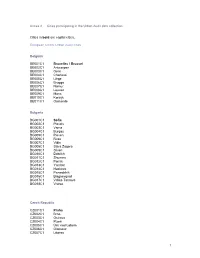

Annex 2 — Cities Participating in the Urban Audit Data Collection

Annex 2 — Cities participating in the Urban Audit data collection Cities in bold are capital cities. European Union: Urban Audit cities Belgium BE001C1 Bruxelles / Brussel BE002C1 Antwerpen BE003C1 Gent BE004C1 Charleroi BE005C1 Liège BE006C1 Brugge BE007C1 Namur BE008C1 Leuven BE009C1 Mons BE010C1 Kortrijk BE011C1 Oostende Bulgaria BG001C1 Sofia BG002C1 Plovdiv BG003C1 Varna BG004C1 Burgas BG005C1 Pleven BG006C1 Ruse BG007C1 Vidin BG008C1 Stara Zagora BG009C1 Sliven BG010C1 Dobrich BG011C1 Shumen BG012C1 Pernik BG013C1 Yambol BG014C1 Haskovo BG015C1 Pazardzhik BG016C1 Blagoevgrad BG017C1 Veliko Tarnovo BG018C1 Vratsa Czech Republic CZ001C1 Praha CZ002C1 Brno CZ003C1 Ostrava CZ004C1 Plzeň CZ005C1 Ústí nad Labem CZ006C1 Olomouc CZ007C1 Liberec 1 CZ008C1 České Budějovice CZ009C1 Hradec Králové CZ010C1 Pardubice CZ011C1 Zlín CZ012C1 Kladno CZ013C1 Karlovy Vary CZ014C1 Jihlava CZ015C1 Havířov CZ016C1 Most CZ017C1 Karviná CZ018C2 Chomutov-Jirkov Denmark DK001C1 København DK001K2 København DK002C1 Århus DK003C1 Odense DK004C2 Aalborg Germany DE001C1 Berlin DE002C1 Hamburg DE003C1 München DE004C1 Köln DE005C1 Frankfurt am Main DE006C1 Essen DE007C1 Stuttgart DE008C1 Leipzig DE009C1 Dresden DE010C1 Dortmund DE011C1 Düsseldorf DE012C1 Bremen DE013C1 Hannover DE014C1 Nürnberg DE015C1 Bochum DE017C1 Bielefeld DE018C1 Halle an der Saale DE019C1 Magdeburg DE020C1 Wiesbaden DE021C1 Göttingen DE022C1 Mülheim a.d.Ruhr DE023C1 Moers DE025C1 Darmstadt DE026C1 Trier DE027C1 Freiburg im Breisgau DE028C1 Regensburg DE029C1 Frankfurt (Oder) DE030C1 Weimar -

51. Club-Brief Dezember 2017

38. Club-Brief Internationaler Club La Redoute Bonn e.V. 51. Club-Brief Dezember 2017 Themen in dieser Ausgabe: Grußwort des Präsidenten Seite 1 Grußwort von Präsident Tilman Mayer zum Jahreswechsel Seite 2 Bericht zur Balkanreise im Septem- ber/Oktober Seite 3 Vor 225 Jahren: Haydn trifft Beethoven General a. D. Harald Kujat über die Neuausrichtung der Bundeswehr Seite 4 Lord Stephen Green spricht zur Lage in Großbritannien nach dem Brexit-Referendum Neue Clubmitglieder seit der letz- ten Ausgabe Präsident Prof. Dr. Tilman Mayer und Generalsekretär Dr. v. Morr mit den Künstlern von „Le Concert Lorrain“ Ausblick auf die nächsten Veran- Stephan Schultz (Cello), Anne-Catherine Bucher (Cembalo) und Patrick Beuckels (Flöte) am 06.12.2017 staltungen Liebe Mitglieder des Internationalen sich - "über Bonn hinaus", wie ein Clubs, Buchtitel von mir lautet. Der Blick zu- rück und der Blick voraus ist uns es ist mir eine Freude und sicherlich gleichermaßen wichtig und möglich. auch eine besondere Aufgabe, das Als Club ist der Internationale Club La Präsidenten-Amt im Internationalen Redoute in Deutschland allenfalls mit Club La Redoute übernommen zu ha- Winterpause dem Übersee Club in Hamburg oder ben. Der Club lebt von seinen ein- dem Industrie-Club in Düsseldorf ver- Das Clubsekretariat ist drucksvollen Mitgliedern wie von hoch- gleichbar. Entsprechend kann ich mei- vom 21.12.2017 bis zum rangigen Vortragenden. Die Geschich- nen Vorgängern seit dem Jahr 2000, te des Clubs belegt, dass Bonn auch 07.01.2018 geschlossen. Gräfin Lambsdorff, Gerd Langguth und heute für viele Referenten ein guter Ort Wiegand Pabsch, nur danken für ihre Wir wünschen Ihnen allen ist, auf Themen sichtbar und öffentlich großartige Leistung, den Club nicht nur besinnliche Feiertage und hinzuweisen und auf hohem Niveau zu zu erhalten, sondern deutlich für neue einen guten Start ins kom- diskutieren. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

NATO – Wikipedia Seite 1 von 24 NATO Koordinaten: 50° 52′ 34″ N, 4° 25′ 19″ O aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Die NATO (englisch North Atlantic Treaty Organization North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) „Organisation des Nordatlantikvertrags“ bzw. Organisation du traité de l’Atlantique Nord (OTAN) Nordatlantikpakt-Organisation; im Deutschen häufig als Atlantisches Bündnis bezeichnet) oder OTAN (französisch Organisation du Traité de l’Atlantique Nord) ist eine Internationale Organisation, die den Nordatlantikvertrag, ein militärisches Bündnis von 28 europäischen und nordamerikanischen Staaten, umsetzt.[4] Das NATO- Hauptquartier beherbergt mit dem Nordatlantikrat das Hauptorgan der NATO; diese Institution hat seit 1967 ihren Sitz in Brüssel. Nach der Unterzeichnung des Nordatlantikpakts am 4. April 1949 – zunächst auf 20 Jahre Flagge der NATO – war das Hauptquartier zunächst von 1949 bis April 1952 in Washington, D.C., anschließend war der Sitz vom 16. April 1952 bis 1967 in Paris eingerichtet worden.[5] Inhaltsverzeichnis ◾ 1 Geschichte und Entwicklung ◾ 1.1 Vorgeschichte ◾ 1.2 Entwicklung von 1949 bis 1984 ◾ 1.2.1 Zwei-Pfeiler-Doktrin ◾ 1.3 Entwicklung von 1985 bis 1990 ◾ 1.4 Entwicklung von 1991 bis 1999 ◾ 1.5 Entwicklung seit 2000 ◾ 1.5.1 Terroranschläge in den USA am 11. September 2001 ◾ 1.5.2 ISAF-Einsatz in Afghanistan ◾ 1.5.3 Irak-Krise Generalsekretär Jens Stoltenberg [1][2] ◾ 1.5.4 Libyen (seit 2014) ◾ 1.5.5 Türkei SACEUR (Supreme US-General Philip M. ◾ 1.6 Krisen-Reaktionstruppe der NATO Allied Commander Breedlove (seit 13. Mai 2013) Europe) ◾ 1.7 NATO-Raketenabwehrprogramm SACT (Supreme Allied General (FRA) Jean-Paul ◾ 2 Auftrag Commander Paloméros (seit September ◾ 2.1 Rechtsgrundlage Transformation) 2012) ◾ 2.2 Aufgaben und Ziele Gründung 4. -

The Mission Continues

No.9 Price: 50 den. May, 2010 ISSN: 1857-6710 MagazineMGANEA z I ofO F theT HE MinistryM I NISTRY ofO F DefenseD E FENSE ofO F theT HE rR epublicE PU b L IC ofO F MaceM A CEDONIAD o n i a A review of the last visit to Afganistan THETHE MISSIONMISSION CONTINUESCONTINUES A DEMONSTRATED HIGH DEGREE OF READINESS AND TRAINING EXERCISE „MACEDONIAN FLASH 06“ DESERVED GROUNDING OF ONE OF THE MOST EXPLOITED ARMY AIRCRAFTS THE HELICOPTER VAM 303 ARM-NATO REPORTING WEAPONS MILITARY HISTORY GAMES AND SIMULATIONS LOGISTIC SUPPORT COMMAND MEMBERS Content: CROWN OF THE LONGTERM PARTNERSHIP The Republic of Macedonia and the United States of America have a high level of co operation. One of the numerous examples of this cooperation is the joint participation of the ARM and the US Vermont National Guard members in the joint contingent “Phoenix” in the ISAF mission in Afghanistan. The joint contingent “Phoenix” consisted of 79 representatives of the Regiment for spe cial operations and the Military Police Battal ion of the RM, together with representatives from the American Army and the Vermont National Guard has begun its mission for Page INTERVIEW training and mentoring of the Afghan Na WITH THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE tional Army and Police thus contributing to OF THE REPUBLIC OF MONTENEGRO, the coalition forces of NATO and the US in 8 MR. BORO VUCHINIC building a democratic society in Afghanistan. This event has an exceptional importance for both Macedonian and American sol diers LOGISTICS SUPPORT standing “shoulder to shoulder” in accom Page CONCEPT OF ARM IN MISSIONS plishing their complex activities in the service of peace and therefore it was marked by the OBSERVATIONS AND NEW CHALLENGES Macedonian Embassy in Washington with 4 an official ceremony. -

Apparamento Napoleone Bonaparte

! Napoleon Bonaparte apartment ! Dedicated to NAPOLEON BONAPARTE - In 1796 the first “Italian Campaign”, after the founding of the Republic of Alba, on April 28th of the same year, Napoleon signed an armistice in Salmatoris Palace of Cherasco that ended hostilities between the French Republic and the Kingdom of Sardinia. On the occasion Napoleon forced Vittorio Amedeo III of Savoy to relinquish the Langhe, the lower Piedmont, Nice and Savoy to France. The decor and furnishing evoke the Empire style through the use of light blue colour, ceilings and walls decorated with stucco works and pilasters, silk and damask fabric in various shades of light blue and gray, black lacquered wood furniture with brass details and dove-gray canopy bed. Paintings in the rooms are showing the passage of Napoleon in Piedmont. !1 ! Type of accommodation: Three-room apartment in the villa ! Location: Ground floor No. of persons: Five adults or Four adults plus two children under ten (sofa bed) Living area: 75 m" Rooms: 3, Bedroom/s: 2, Bathrooms: 2 Furnishing: Elegant, refined, and evocative of Imperial Style, wooden parquet, travertine marble floor. Equipment: Satellite TV, Wi-Fi Internet connection (included). Air conditioning, floor heating. Furnished kitchen. Common area: washing machine, iron/ironing board, locker View: panoramic Access/parking: Garage in the basement. Pool: Yes, shared with the guests of the other apartments !2 ! Subdivision of spaces Entrance - Living room: Living room with sofa bed, pouf and armchair, peninsula table with 4 chairs, console, library, access to the large panoramic terrace and direct access to the pool. Linear kitchen in the living room equipped with a 4-burner induction hob, oven, dishwasher, fridge, small freezer, coffee machine, dishes set, water and wine glasses, cutleries and cooking accessories. -

Redefining German Security: Prospects for Bundeswehr Reform

REDEFINING GERMAN SECURITY: PROSPECTS FOR BUNDESWEHR REFORM GERMAN ISSUES 25 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REDEFINING GERMAN SECURITY: PROSPECTS FOR BUNDESWEHR REFORM GERMAN ISSUES 25 supp-sys front text kj rev.p65 1 09/19/2001, 11:30 AM The American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) is a center for advanced research, study, and discussion on the politics, culture, and society of the Federal Republic of Germany. Established in 1983 and affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University but governed by its own Board of Trustees, AICGS is a privately incorporated institute dedicated to independent, critical, and comprehensive analysis and assessment of current German issues. Its goals are to help develop a new generation of American scholars with a thorough understanding of contemporary Germany, deepen American knowledge and understanding of current German developments, contribute to American policy analysis of problems relating to Germany, and promote interdisciplinary and comparative research on Germany. Executive Director: Jackson Janes Board of Trustees, Cochair: Fred H. Langhammer Board of Trustees, Cochair: Dr. Eugene A. Sekulow The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©2001 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-60-1 Additional copies of this AICGS German Issue are available from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265-9531, E-mail: [email protected], Web: http://www.aicgs.org [ii] AICGS German Issues Volume 25 · September 2001 supp-sys front text kj rev.p65 2 09/19/2001, 11:30 AM C O N T E N T S Preface .............................................................................................. -

Helen Burke Ledbury a Thesis Submitted to the University of Sheffield in Candidature for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Depa

THE TRAGEDIES OF MAMA RosA GkLvEZ DE CABRERA (1768-1806) Helen Burke Ledbury A thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hispanic Studies April 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The researchpresented in this thesiswas carriedout betweenOctober 1994and April 2000 in the Departmentof HispanicStudies at the Universityof Sheffieldunder the supervisionof Dr. Philip Deacon.The projectwas supportedfor threeyears as part of the UniversityFees and Bursary Scheme. A period of archivalresearch in July 1996was fundedaccording to the termsof the PetrieWatson Exhibition. I would like to thank Professor A. A. Heathcote for supporting my initial applications for funding and Professor N. Round for subsequentlyaccepting me as a postgraduate student, Dr. Tim Lewis for enrolling me as Graduate Tutor in Spanishin the Modem LanguagesTeaching Centre, and Dr. JohnEngland for encouragingand supporting me as a tutor in the Department of Hispanic Studies. The successfulcompletion of this thesisis due,in part, to Dr Philip Deacon whose expert guidance through the initial phasesand scrupulous direction during the final stagesof my project haveproved invaluable. Dr. Deacon'ssupervision has been both intellectuallydemanding and rigorous throughout and I would Re to thank him for his advice, practical support and ongoing interest in my work. I must also acknowledge the support of colleagues,especially Jane Woodin, Isabel Diez, Antonio Barriga, Nashy Bonelli, Puri Trabada and Julia Falc6n and the understanding and loyalty of friends, especiallyNuria Gon7Aez, Jordi Doce, Catherine Smith, Barry Rawlins, Cristina Vald6s, Isabel Vencesli and Rekha Narula. I must expressmy deepestgratitude to Valerieand Vincent Burke, who always ensuredI was neverdenied an opportunityto further my knowledgeand learning. -

The Wind-Band Phenomenon in Italy: a Short Socio-Historical Survey and Its Effect on Popular Musical Education

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 11; November 2020 pp. 1-21 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Doi: 10.48150/jlah.v1no11.2020.a1 The Wind-Band phenomenon in Italy: A short socio-historical survey and its effect on popular musical education Prof. Emanuele Raganato University of Salento (Italy) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Wind-Bands are musical ensembles existing all around the world, but with a stronger traditional presence in certain regions of the globe. One of these regions is Southern Italy. In this geographical area, this phenomenon developed historically over two centuries and has taken on shapes now considered traditional. Thanks to Wind-Bands, historically, millions of Italians have participated in collective musical activities as musicians or listeners and have been trained in music. Wind-Bands, in fact, for most of the 19th and 20th centuries have been the main means of spreading musical culture in Italy and the world and the only way for working class youth to learn a musical instrument. Thanks to a careful examination of the publications on the local Wind- Bands through the historiographic method, we have outlined a frame that explains the change in the social role of the Bands from the end of the 19th century to today. The conclusion is that today the Wind-Band has assumed a new morphology that, however, would deserve to be reconsidered taking into account the new social changes taking place (emigration of the middle class, immigration, social reforms and the music education system, and so on.) to understand if, as in the past, the Wind-Band can still have a fundamental functional role in local communities for social cohesion and music education, or at least imagine future scenarios to reconsider this role. -

Germany and the Use of Force.Qxd 30/06/2004 16:25 Page 118

Longhurst, Germany and the use of force.qxd 30/06/2004 16:25 Page 118 6 The endurance of conscription Universal conscription is an element of Germany’s security insurance and will continue to be indispensable.1 I believe that conscription is an essential instrument for the Bundeswehr’s integration into society. Therefore, it shall remain.2 The conscription puzzle When considered against the expansion of the Bundeswehr’s remit dur- ing the 1990s and the associated efforts at restructuring its armed forces, Germany’s stalwart commitment to retaining conscription is an area of profound stasis, an anomaly warranting further investigation. In the face of ever-more acute strategic, economic and social challenges to the utility of compulsory military service since the ending of the Cold War, conscription was maintained and developed in Germany in the 1990s by both the CDU- and the SPD-led Government to enhance its rele- vance and thus ensure its survival. Moreover, the issue of conscription’s future, whenever it has been debated in Germany over the past decade, has been hampered by the overwhelming support given to the practice by the Volksparteien, as well as the Ministry of Defence; as a conse- quence, no serious consideration has been given to alternatives to conscription. This situation sets Germany apart from countries across Europe (and beyond) where the trend has been away from the mass-armed force pre- missed on compulsory military service and towards fully professional smaller forces. Germany’s lack of engagement with the issue of con- scription derives from the prevailing belief among the political and mil- itary elite that, stripped of its compulsory military service element, the Kerry Longhurst - 9781526137401 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 05:08:06PM via free access Longhurst, Germany and the use of force.qxd 30/06/2004 16:25 Page 119 The endurance of conscription 119 Bundeswehr would become irretrievably undemocratic and that unde- sirable changes to the form and substance of Germany’s foreign and security policy would follow. -

Aus Politik Und Zeitgeschichte 43/2008 ´ 20

APuZ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 43/2008 ´ 20. Oktober 2008 Auûen- und Sicherheitspolitik Peter Bender Deutsche Auûenpolitik: Vernunft und Schwåche Dieter Weiss Deutschland am Hindukusch Stefan Fræhlich Deutsche Auûen- und Sicherheitspolitik im Rahmen der EU Carlo Masala Neuorientierung deutscher Auûen- und Sicherheitspolitik Jærg Faust ´ Dirk Messner ¹Ankerlånderª als auûenpolitische Herausforderung Michael Hennes Das pazifische Jahrhundert Harald Mçller Der ¹demokratische Friedenª und seine Konsequenzen Beilage zur Wochenzeitung Das Parlament Editorial Seit dem Zerfall der Sowjetunion hat sich die internationale Ordnung grundlegend veråndert. Von zwei ehemals dominieren- den Blæcken sind allein die Vereinigten Staaten als fçhrender weltpolitischer Akteur verblieben. Doch inzwischen haben sich weitere Machtzentren entwickelt, sodass sich ein neues multipo- lares System internationaler Beziehungen bereits abzeichnet. Mit China, Indien, Brasilien sowie weiteren ehemaligen Entwick- lungs- bzw. Schwellenlåndern beanspruchen regionale Fçh- rungsmåchte zunehmend Mitsprache auf der weltpolitischen Bçhne. Drångende Zukunftsfragen, wie die des Klimawandels oder der knapper werdenden Ressourcen, sind nur gemeinsam mit diesen Staaten zu beantworten, die ganz eigene (teilweise ge- gensåtzliche) Interessen verfolgen. Deutschland hat auûenpolitisch zwar an Gewicht gewonnen, scheint aber knapp 20 Jahre nach der Wiedervereinigung noch auf der Suche nach seiner Rolle in dieser unçbersichtlicheren Weltordnung zu sein. Eine gemeinsame Auûenpolitikder Euro- påischen Union ist bisher nur in Ansåtzen vorhanden. Gleichzei- tig setzen die USA verstårkt auf Allianzen auûerhalb der NATO oder der UNO, um ihre Interessen durchzusetzen. Dennoch werden die EU und die USA auch in Zukunft Deutschlands wichtigste auûen- und sicherheitspolitische Partner bleiben. Dass der auûenpolitische Bedeutungszuwachs der Bundesre- publikauch mit gesteigerten Erwartungen an sie verbunden ist, zeigt der Bundeswehreinsatz in Afghanistan, wo die Alliierten auf ein græûeres Engagement der Deutschen drången. -

Adenaueri Saladus Ja Bundeswehri Sünnitund Kloostrimüüride Varjus

ADENAUERI SALADUS JA BUNDESWEHRI SÜNNITUND KLOOSTRIMÜÜRIDE VARJUS ÄÄREMÄRKUSI ÜHE KÜLMA SÕJA LAPSE – BUNDESWEHRI – SÜNNILOO KOHTA ANDRES SAUMETS ■ Sissejuhatuse asemel: uus riigikodanik uues sõjaväevormis – kas pelgalt ideaal? Hall värv andis tooni, kui 12. novembril 1955 üks ebatavaline grupp ini- mesi – enamik kandis tsiviil-, ent mõned ka vormirõivastust – kogunes Bonnis ühte tumeda riidega ülelöödud ratsutamishalli ning seisis seal pinevil närvilisusega. Kõlasid sõnad: “Me kanname vastutust tulevikus meie kätte usaldatud noorte sõjaväevormis riigikodanike eest.” Sada üks isikut kogunesid pidulikku smokingülikonda riietatud föderaalse kaitseministri Theodor Blanki ette. Tema käest said ametisse määramise tunnistused uude, kaherealisse sõjaväevormi riietatud kaks kõige kõrgemat kindralit, kindralleitnandid Adolf Heusinger ja Hans Speidel, ülejäänud ohvitserid ja kuus allohvitseri. Blank visandas selle “uue Wehrmachti” poliitilise profiili, mis peaks nüüdsest olema Saksamaa riikliku korra võrdõiguslik liige ja andma panuse kaitsevalmiduse suurenemiseks rahu kindlustamisel Euroo- pas. Halli eesseinas kõrgus krüsanteemikimpudega raamistatud kõnetribüüni kohal Liitvabariigi lipuga raamistatud, peaaegu viie meetri kõrgune Raudrist – Preisi Raudrist, mis oli viimati olnud Wehrmachti aumärk. Pea- aegu kõik kohalviibijad – ka need, kel polnud seljas sõjaväevormi – kandsid sõjas saadud aumärgina Raudristi.1 Bundeswehri asutamisse suhtuti sõjajärgsel Saksamaal üsna vastakate tunnetega. Eespool toodud kirjeldusest võib aduda, et suhtumine oli