MATURING out an Empirical Study of Personal Histories and Processes in Hard-Drug Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 26, 1995

Volume$3.00Mail Registration ($2.8061 No. plusNo. 1351 .20 GST)21-June 26, 1995 rn HO I. Y temptation Z2/Z4-8I026 BUM "temptation" IN ate, JUNE 27th FIRST SIN' "jersey girl" r"NAD1AN TOUR DATES June 24 (2 shows) - Discovery Theatre, Vancouver June 27 a 28 - St. Denis Theatre, Montreal June 30 - NAC Theatre, Ottawa July 4 - Massey Hall, Toronto PRODUCED BY CRAIG STREET RPM - Monday June 26, 1995 - 3 theUSArts ireartstrade of and andrepresentativean artsbroadcasting, andculture culture Mickey film, coalition coalition Kantorcable, representing magazine,has drawn getstobook listdander publishing companiesKantor up and hadthat soundindicated wouldover recording suffer thatKantor heunder wasindustries. USprepared trade spokespersonCanadiansanctions. KeithThe Conference for announcement theKelly, coalition, nationalof the was revealed Arts, expecteddirector actingthat ashortly. of recent as the a FrederickPublishersThe Society of Canadaof Composers, Harris (SOCAN) Authors and and The SOCANand Frederick Music project.the preview joint participation Canadian of SOCAN and works Harris in this contenthason"areGallup the theconcerned information Pollresponsibilityto choose indicated about from.highway preserving that to He ensure a and alsomajority that our pointedthere culturalthe of isgovernment Canadiansout Canadian identity that in MusiccompositionsofHarris three MusicConcert newCanadian Company at Hallcollections Toronto's on pianist presentedJune Royal 1.of Monica Canadian a Conservatory musical Gaylord preview piano of Chatman,introducedpresidentcomposers of StevenGuest by the and their SOCAN GellmanGaylord.speaker respective Foundation, and LouisThe composers,Alexina selections Applebaum, introduced Louie. Stephen were the originatethatisspite "an 64% of American the ofKelly abroad,cultural television alsodomination policies mostuncovered programs from in of place ourstatisticsscreened the media."in US; Canada indicatingin 93% Canada there of composersdesignedSeriesperformed (Explorations toThe the introduceinto previewpieces. -

Russell-Mills-Credits1

Russell Mills 1) Bob Marley: Dreams of Freedom (Ambient Dub translations of Bob Marley in Dub) by Bill Laswell 1997 Island Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance, image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings: Russell Mills 2) The Cocteau Twins: BBC Sessions 1999 Bella Union Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) 3) Gavin Bryars: The Sinking Of The Titanic / Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet 1998 Virgin Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance and image melts: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 4) Gigi: Illuminated Audio 2003 Palm Pictures Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Jean Baptiste Mondino 5) Pharoah Sanders and Graham Haynes: With a Heartbeat - full digipak 2003 Gravity Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Paintings and assemblages: Russell Mills 6) Hector Zazou: Songs From The Cold Seas 1995 Sony/Columbia Art and design: Russell Mills and Dave Coppenhall (mc2) Design assistance: Maggi Smith and Michael Webster 7) Hugo Largo: Mettle 1989 Land Records Art and design: Russell Mills Design assistance: Dave Coppenhall Photography: Adam Peacock 8) Lori Carson: The Finest Thing - digipak front and back 2004 Meta Records Art and design: Russell Mills (shed) Design assistance: Michael Webster (storm) Photography: Lori Carson 9) Toru Takemitsu: Riverrun 1991 Virgin Classics Art & design: Russell Mills Cover -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Understanding Conflict Dynamics: A Comparative Analysis of Ethno-Separatist Conflicts in India and the Philippines Voor een beter begrip van conflictdynamiek: een vergelijkende analyse van etnisch- seperatistische conflicten in India en de Filippijnen (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 18 oktober 2013 des middags te 2.30 uur door Alastair Grant Reed geboren op 7 december 1978 te Oxford, United Kingdom PROMOTOREN: Prof.dr. D.A. Hellema Prof.dr. B.G.J. de Graaff Prof.dr. I.G.B.M. Duyvesteyn This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO). CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix 1 Introduction 1 The research question 3 A survey of theories on irregular conflicts 7 Causes of conflicts 9 How conflicts progress after they have started 15 The role of the state 21 The population and popular support 26 The role of peace processes 28 Theories of foreign support/international relations 30 Theories on geography 31 How violence ends 33 Theoretical insights 35 The research model 36 Research design 44 Case study selection 49 Why Asia? 51 Originality claim 56 2 The Naga Insurgency 59 Part 1: The background to the conflict 59 Part 2: The phases of the Naga Insurgency 64 Phase 1: 1947 to 1957 – a national struggle 65 Phase 2: 1957 to 1964 – the road -

Observation of Iron Ore Beneficiation Within a Spiral

Observation of iron ore beneficiation within a spiral concentrator by positron emission particle tracking of large (Ø=1440m) and small (Ø=58m) hematite and quartz tracers Boucher, Darryel; Deng, Zhoutong; Leadbeater, Thomas; Langlois, Raymond; Waters, Kristian E. DOI: 10.1016/j.ces.2015.10.018 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Boucher, D, Deng, Z, Leadbeater, T, Langlois, R & Waters, KE 2016, 'Observation of iron ore beneficiation within a spiral concentrator by positron emission particle tracking of large (Ø=1440m) and small (Ø=58m) hematite and quartz tracers', Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 140, pp. 217-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2015.10.018 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: After an embargo period this document is subject to a Creative Commons Non-Commercial No Derivatives license Checked Feb 2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Strategies for Unbridled Data Dissemination: an Emergency Operations Manual

Strategies for Unbridled Data Dissemination: An Emergency Operations Manual Nikita Mazurov PhD Thesis Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London 1 Declaration To the extent that this may make sense to the reader, I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Nikita Mazurov 2 Acknowledgements The notion that the work in a thesis is ‘one’s own’ doesn’t seem quite right. This work has benefited from countless insights, critiques, commentary, feedback and all potential other manner of what is after all, work, by those who were subjected to either parts or the entirety of it during encounters both formal and informal. To say nothing of the fact that every citation is an acknowledgement of prior contributory work in its own right. I may have, however, mangled some or all of the fine input that I have received, for which I bear sole responsibility. Certain images were copied from other publications for illustrative purposes. They have been referenced when such is the case. Certain other images were provided by sources who will rename anonymous for reasons of safety. Assistance with technical infrastructure in establishing a server for part of the project was provided by another anonymous source; anonymous for the same reason as above. 3 Abstract This project is a study of free data dissemination and impediments to it. Drawing upon post-structuralism, Actor Network Theory, Participatory Action Research, and theories of the political stakes of the posthuman by way of Stirnerian egoism and illegalism, the project uses a number of theoretical, technical and legal texts to develop a hacker methodology that emphasizes close analysis and disassembly of existent systems of content control. -

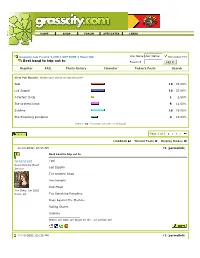

Best Band to Trip out to Password Log In

HOME SHOP FORUM AFFILIATES LINKS Grasscity.com Forums > CHILL OUT ZONE > Music Hall User Name User Name Remember Me? Best band to trip out to Password Log in Register FAQ Photo Gallery Calendar Today's Posts Search View Poll Results: Whats your choice of stoned tunes? Tool 10 25.00% Led Zepplin 10 25.00% A Perfect Circle 1 2.50% The Grateful Dead 5 12.50% Sublime 10 25.00% The Smashing pumpkins 4 10.00% Voters: 40. You may not vote on this poll Page 1 of 3 1 2 3 > LinkBack Thread Tools Display Modes 11-10-2002, 10:13 AM #1 (permalink) Best band to trip out to GreenLeaf Tool Revolutionary Weed Led Zepplin Smoker The Grateful Dead Jimi Hendrix Pink Floyd Join Date: Jun 2002 Posts: 24 The Samshing Pumpkins Rage Against The Machine Rolling Stones Sublime __________________ When are born we begin to die...so smoke on! 11-10-2002, 05:32 PM #2 (permalink) trip? I had my best trip...absolute best by far to Ben Harper, Fight for Your Mind. so intense, so felt like the music passed right through my body sensimil __________________ Old School Stoner If riding in an airplane is flying, then riding in a boat is swimming. If you want to experience the element, then get out of the vehicle. Once you have tasted flight, you will walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been and there you long to return. Join Date: Nov 2001 Location: 2,914 miles from the jersey shore Posts: 6,754 11-11-2002, 11:51 PM #3 (permalink) Best tripping music Zeppelin Oisin Tricky Registered User Miles Davis Nick Drake The Coral Join Date: Sep 2002 Bob Dylan Posts: 7 Bob Marley Jimmy Hendrix Pink Floyd The Beatles Mos Def Funkadelic The Cure Radiohead White Stripes Dizzy Gillespie Louis Armstrong Velvet Underground Boards of Canada 11-16-2002, 07:09 PM #4 (permalink) Beatles Zoot23 Pink Floyd Registered User Grateful Dead Join Date: Nov 2002 Phish Posts: 19 JPT Scare Band www.jptscareband.com Widespread Panic __________________ Is Art a reflection of Life? Or does Life imitate Art? Last edited by Zoot23 : 11-23-2002 at 07:53 PM. -

Artikel-Nr. Komponist Titel Interpret/In Inhalt Cds Preis 0137702 Acoustic

AKTION Gesamtliste Inhalt Artikel-Nr. Komponist Titel Interpret/in Preis CDs 0137702 Acoustic Soul India.Arie 1 5,50 € 0144812 The Way I Feel Shand, Remy 1 5,50 € 0160832 Legacy:The Greatest Hits Coll Boyz Ii Men 1 5,50 € 0383002 Dancing On The Ceiling Richie, Lionel 1 5,50 € 0640212 Let'S Get It On Gaye, Marvin 1 5,50 € 0640222 What'S Going On Gaye, Marvin 1 5,50 € 0656032 Songs For A Taylor Bruce, Jack 1 5,50 € 0656042 Things We Like Bruce, Jack 1 5,50 € 0761732 In The Jungle Groove Brown, James 1 5,50 € 1128462 No More Drama Blige, Mary J 1 5,50 € 1532592 Mama'S Gun Badu, Erykah 1 5,50 € 1596382 All The Greatest Hits Ross, Diana 1 5,50 € 1717881 Reflections - A Retrospective Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 1752030 Growing Pains Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 1756451 The Orchard Wright,Lizz 1 5,50 € 1773562 Year Of The Gentleman Ne-Yo 1 5,50 € 1781241 One Kind Favor B.B. King 1 5,50 € 1782745 Just Go Richie,Lionel 1 5,50 € 2714783 The Definitive Collection Jackson,Michael 1 5,50 € 2722270 I Want You Back! Unreleased MastersJackson,Michael 1 5,50 € 2724516 All Or Nothing Sean,Jay 1 5,50 € 2725654 Stronger withEach Tear Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 2732676 New Amerykah Part Two (Return Of TheBadu,Erykah Ankh) 1 5,50 € 2745084 Icon Brown,James 1 5,50 € 2745092 Icon Gaye,Marvin 1 5,50 € 2747250 Icon White,Barry 1 5,50 € 2747254 Icon Wonder,Stevie 1 5,50 € 2757674 Rokstarr (Special Edt.) Cruz,Taio 1 5,50 € Seite 1 von 142 Inhalt Artikel-Nr. -

Resilience Mastery by Bradley Hook

i RESILIENCE MASTERY 11 KEYS TO UPGRADE HUMAN PERFORMANCE BY BRADLEY HOOK Resilience Mastery 11 Keys to Upgrade Human Performance © 2020 by Bradley Hook All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-0-473-51079-4 Cover Design by Evgeniya Ignatova No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written per- mission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embod- ied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please email [email protected]. D Learn, play and lean into feart REVIEW If you enjoy this book please do leave a review on Amazon or GoodReads. Amazon: https://amzn.to/2JrgCOm CONNECT To connect with Bradley Hook please email [email protected] Brad is a partner at the Resilience Institute, providing resilience training and the Resilience App to thousands of organisations around the world. https://resiliencei.com Brad is the founder of Tech Wellbeing - dedicated to en- abling positive relationships with technology. https://techwellbeing.org CONTENTS Introduction 1 Focus 7 Purpose 27 Fulfilment 45 Optimism 65 Vitality 85 Presence 105 Decisiveness 121 Bounce 137 Assertiveness 153 Sleep Quality 171 Values Alignment 189 Conclusion 205 INTRODUCTION Imagine the movie of your life. Is it fuzzy and out of focus or masterfully crafted? Does the storyline flit haphazardly or is the narrator driven by a sense of purpose? It doesn’t matter whether the movie of your life is a comedy, tragedy, drama or epic adventure – what matters is that you get to act, produce and direct. -

MILES-MASTERSREPORT-2009.Pdf (142.7Kb)

Copyright By Scott Gordon Miles 2009 The Unicorn Stays in the Picture: Deconstructing the “Chosen One” Myth in the Young Adult Fantasy Film by Scott Gordon Miles, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2009 The Report committee for Scott Gordon Miles Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: The Unicorn Stays in the Picture: Deconstructing the “Chosen One” Myth in the Young Adult Fantasy Film APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE Supervisor:________________________ Richard Lewis ________________________ Steven Dietz Acknowledgements This report and the screenplay discussed herein would not have been possible without the consistent efforts and goodwill of my classmates and professors, who steered me in the right direction and always cared more for the story than my feelings. And for that, they have my eternal gratitude. iv The Unicorn Stays in the Picture: Deconstructing the “Chosen One” Myth in the Young Adult Fantasy Film by Scott Gordon Miles, M.F.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2009 SUPERVISOR: Richard Lewis This report covers the process of developing, writing and revising the original screenplay “Magic For Losers.” When famous child wizard Daphne Grimsby is abducted by villainous foes, her loser brother Darwin must reluctantly venture into a magical world to save her. The script heavily relies on the concepts and ideas evoked from the Hero’s Journey model of storytelling. I have also structured this report on the same model, as in its own way, completing a feature length screenplay is fraught with the same trials and tribulations. -

Előadó Album Címe Hanghordozó Kiadó Release Oszlop1 Oszlop2

Előadó Album címe Hanghordozó Kiadó Release Oszlop1 Oszlop2 Oszlop3Oszlop4 Oszlop5 A CAMP A CAMP CD STOCK 2001.08.16 A FINE FRENZY BOMB IN A BIRDCAGE CD VIRGI 2009.08.27 A FINE FRENZY PINES CD VIRGI 2012.10.11 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS BEST OF -12TR- CD JIVE 2005.12.05 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS PLAYLIST-VERY BEST OF CD EPIC 1990.06.30 A TEENS GREATEST HITS CD STOCK 2004.05.20 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST LOW END THEORY CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAV CD JIVE 2003.08.28 A.F.I. SING THE SORROW CD UNIV 2003.04.22 A.F.I. DECEMBER UNDERGROUND CD IN.SC 2006.06.01 AALIYAH AGE AIN'T NOTHIN' BUT A N CD JIVE 2005.12.05 AALIYAH AALIYAH CD UNIV 2007.10.04 AALIYAH ONE IN A MILLION CD UNIV 2007.10.04 AALIYAH I CARE 4 U CD UNIV 2007.11.29 AARSETH, EIVIND ELECTRONIQUE NOIRE CD VERVE 1998.05.11 AARSETH, EIVIND CONNECTED CD JAZZL 2004.06.03 ABBA 18 HITS CD UNIV 2005.08.25 ABBA RING RING + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA WATERLOO + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ABBA + 2 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ARRIVAL + 2 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA ALBUM + 1 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA VOULEZ-VOUS + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA SUPERTROUPER + 3 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA VISITORS + 5 CD POLYG 2001.06.21 ABBA NAME OF THE GAME CD SPECT 2002.10.07 ABBA CLASSIC:MASTERS. -

Nine Inch Nails

[ Nine Inch Nails Tim es, they are a changin’ % Music critic Chris Yunt takes The CLC discusses its current Tuesday t a look at Trent Reznor’s latest remix, structure and whether it B y Things Falling Apart. needs to be revamped. JANUARY 23, ■ scene ♦ page 12 News ♦ page 3 2 0 0 1 O bserver The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s VOL XXXIV NO. 71____________________________________________________________________________________________________I ITTIV/OBSF.RVI R.N D. E P U Admitting a class of colors Notre Dame and Saint Mary's actively recmit minority students to create a diverse environment and enhance students ’ overall education Editor's note: In honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. ♦ Targeting celebrations on campus. minorities early The Observer explores critical for SMC Moving diversity issues in a four- part series. Part one By NOREEN GILLESPIE Toward examines the challenges News Writer and successes of recruit the ing minority applicants. As a ju n io r in high school, Adriana Garces Dream ♦ ND identifies, knew she was going to pursues high college. Part I: She just didn’t know Recruiting talent minorities how she was going to get there. By MIKE CONNOLLY As the South Bend News Writer native sat in her classes at Washington High School, With the same vigor it she mulled over several pursues the top high school different plans — she athletes in America, the could move to Texas, and University uses phone calls, try to go to school there, mailing and campus visita or attend community col tions to lure some of the lege at Indiana University most highly qualified minor at South Bend, close to ity students to the Golden home. -

Null Landing

null landing © 2020 !1 black metallurgy 4 learning to weld 5 lulls 6 poem (untitled no. 1) 7 construction 8 poem for matou 9 plastic/pattern/people 10 metal work 11 vivarium 12 architecture of containment 14 salt marsh 15 the beauty of the gathering 16 resurfaces 17 virtual work principle for a deformable body 18 still. life. 19 sublunary 20 this is an installation 21 another link to life 22 bruce’s beach 23 fractal 24 a note on fabrication 25 marshlands, or oscillations 27 poem (for toni morrison) 28 perching birds (passeriformes) 29 disemboguement 30 null space 31 lustration 32 song 34 who said it was simple? 35 poem (untitled no. 2) 36 fuvial processes 37 poem (for my psychiatrist) 38 teem 39 feet/ feet/ fuse 40 the view of the garden from the kitchen window 41 n fux 42 squall/ bluster 43 so many constellations 44 poem (untitled no. 3) 46 an interstitial character 47 gesture/sound/site (a love poem) 48 poem (kill) 49 the sundarbans 50 !2 the smallest drama 52 soleil 53 poem (untitled no. 4) 54 episodes 55 displaced fracture of the right hand 56 sweet alimatou 57 a moment of inertia 58 fusillade 59 still water 60 before even sun sets 61 parable of the choir (for the chorister) 62 broken silence 63 index/ fux 64 n poetics 65 poem (for oscar) 66 baby berceuse 67 of words, bodies 68 where do the early birds meet the night owls? 69 palustrine 70 liner notes 71 !3 black metallurgy redress !4 LEARNING TO WELD we have waited so long to surface to land to end up wind up as aggregations of disharmony dans un état de changement perpétuel, m continuel1 as food tide and ebb tide bring, regardless of anything else an uncertain energy to life re combine and shed/splice form anew, wordsmith.