Railway Goods Sheds and Warehouses Introductions to Heritage Assets Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paterson Points NEWSLETTER of the RAIL MOTOR SOCIETY INCORPORATED

Paterson Points NEWSLETTER OF THE RAIL MOTOR SOCIETY INCORPORATED FEBRUARY 2014 Patron ~ Rear Admiral Peter Sinclair AC Inside... ~ Society News ~ Tour Reports ~ Operations Diary ~ AGM Saturday 22 March Clear of the main line, the CPHs stabled for the night adjacent to Gilgandra’s loading bank. Photo: James Brook PRINT POST APPROVED PP100003904 Society News Operations Report Annual General Meeting ~ Bruce Agland, Operations Manager Members are advised that this important meeting will be held on Saturday 22nd March commencing at 1000hrs, the Operations for 2014 formal meeting notice and associated forms are included 4 January Dungog (CPH), Archer with this newsletter. 14-15 January Junee (402), ARTC Election of Five Board Members 19 January Nowra (620), ARHS In accordance with the new Constitution, five of those 25 January Tamworth (620), Maitland Rotary members of the Board elected at the AGM in 2013 will 15-16 February Metro Freight Lines (620), retire but will be eligible for re-election should they decide Epping Model Railway Club to nominate again. 8 March Metro (620), Private Charter 4-6 April Orange (620), Travelscene Membership Renewals 12-13 April Steamfest, (TBC), The Rail Motor Society Members are advised that your membership subscription for 14-15 April Binnaway (402), ARHS Queensland 2014 that was due on 1st January is now OVERDUE. 3 May Denman (620), Kalverla Unfinancial members are not eligible to vote at the Annual 3 May Denman (CPH), Ede General Meeting and proxy forms will not be validated if you 17-18 May Gulgong (CPH), Scott are unfinancial before the start of the meeting. -

Eastern Railway

2.1.1 पूव रेलवे EASTERN RAILWAY 20192019----2020 के िलए पƗरसंपिēयĪ कƙ खरीद , िनमाϕण और बदलाव Assets-Acquisition, Construction and Replacement for 2019-20 (Figures in thousand of Rupees)(आंकड़े हजार Đ . मĞ) पूंजी पूंजी िनिध मूआिन िविन संिन रारेसंको जोड़ िववरण Particulars Capital CF DRF. DF SF RRSK TOTAL 11 (a ) New Lines (Construction) 70,70,00 .. .. .. .. .. 70,70,00 14 G Gauge Conversion 2,00,00 .. .. .. .. .. 2,00,00 15 ह Doubling 9,80,95 .. .. .. .. .. 9,80,95 16 - G Traffic Facilities-Yard 21,22,84 .. 90,25 13,22,19 .. 29,97,50 65,32,78 G ^ G Remodelling & Others 17 Computerisation 3,51,00 .. 12,41,30 62,00 .. .. 16,54,30 21 Rolling Stock 30,24,90 .. .. 7,66 .. 37,56,01 67,88,57 22 * 4 - Leased Assets - Payment of 518,12,69 205,67,31 .. .. .. .. 723,80,00 Capital Component 29 E G - Road Safety Works-Level .. .. .. .. .. 38,60,00 38,60,00 Crossings. 30 E G -/ Road Safety Works-Road .. .. .. .. .. 113,06,79 113,06,79 Over/Under Bridges. 31 Track Renewals .. .. .. .. .. 587,20,77 587,20,77 32 G Bridge Works .. .. .. .. .. 69,69,90 69,69,90 33 G Signalling and .. .. .. .. .. 83,25,97 83,25,97 Telecommunication 36 ^ G - G Other Electrical Works excl 1,34,17 .. 4,38,47 2,62,72 .. 5,08,29 13,43,65 K TRD 37 G G Traction Distribution Works 16,00,00 .. .. .. .. 110,59,55 126,59,55 41 U Machinery & Plant 5,16,94 . -

Camden Railway Station a Reminder of Incessant Government Under-Funding of the Nsw Rail System

CAMDEN RAILWAY STATION A REMINDER OF INCESSANT GOVERNMENT UNDER-FUNDING OF THE NSW RAIL SYSTEM These notes relate only to the history of the passenger facilities at the Camden terminus. The history of the branch line has already been published. Alan Smith, a long-time member of the Australian Railway Historical Society and a frequent volunteer at its Resource Centre, won the competition to choose the cover photo for these notes. It seems strange that Alan chose a photograph not of the terminus but of an intermediate station, Kenny Hill. Why? Alan considered that this was the “iconic image of the challenges that existed in the day-to-day operation of the Camden line”. Specifically, the photograph shows the absence of priority given to passengers when the train crew had to decide whether to convey people or freight. It should be of no surprise that people lost out. Bob Merchant took this undated photograph on a day when the steam locomotive simply could not succeed in climbing the gradient. In the composition of the train were two milk pots. They were next to the engine. There was no question of reversing the train to Narellan, shunting and then proceeding with the only the passenger car. Why not? Because the milk pots had to be attached to No. 32 Express Goods or there would be serious trouble for the train crew if the Camden milk did not accompany the other milk vans from Bowral and Menangle on the train. What! Passengers are voters. Not so much in 1963 when the line closed. -

Rail Terminal Facilities

THE ASIAN JOURNAL Volume 16 April 2009 Number 1 JOURNAL OF TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE RAIL TERMINAL FACILITIES Infrastructural Challenges for India’s Future Economic Growth: Hopes from Railways G. K. Chadha Terminals on Indian Railways S. B. Ghosh Dastidar Port Based Rail Freight Terminal Development – Design and Operational Features Poul V. Jensen & Niraja Shukla New Management Model for Railway Freight Terminals Indra Ghosh Bulk Freight Terminals on Indian Railways: Evolution and Options G. D. Brahma Freight Terminal Development Sine Qua Non of Logistics Development Sankalp Shukla Multimodal Hubs for Steel Transportation and Logistics Juergen Albersmann CASE STUDY Jawaharlal Nehru Port: Terminal and Transit Infrastructure Raghu Dayal THE ASIAN JOURNAL Editorial Board K. L. Thapar (Chairman) Dr. Y. K. Alagh Prof. S. R. Hashim T.C.A. Srinivasa-Raghavan © April 2009, Asian Institute of Transport Development, New Delhi. All rights reserved ISSN 0971-8710 The views expressed in the publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong or that of the Board of Governors of the Institute or its member countries. Published by Asian Institute of Transport Development 13, Palam Marg, Vasant Vihar, New Delhi-110 057 INDIA Phone: +91-11-26155309 Telefax: +91-11-26156294 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.aitd.net CONTENTS Introductory Note i Infrastructural Challenges for India’s Future Economic Growth: Hopes from Railways 1 G. K. Chadha Terminals on Indian Railways 27 S. B. Ghosh Dastidar Port Based Rail Freight Terminal Development – Design and Operational Features 40 Poul V. -

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Collision at Swanage station 16 November 2006 Report 35/2007 September 2007 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2007 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Rail Accident Investigation Branch 3 Report 35/2007 www.raib.gov.uk September 2007 Collision at Swanage station 16 November 2006 Contents Introduction 6 Summary of the report 7 Key facts about the accident 7 Immediate cause, causal and contributory factors, underlying causes 7 Recommendations 8 The Accident 9 Summary of the accident 9 Location 9 The parties involved 10 External circumstances 10 The infrastructure 10 The train 12 Events -

Operating Manual for Indian Railways

OPERATING MANUAL FOR INDIAN RAILWAYS GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (RAILWAY BOARD) INDEX S.No. Chapters Page No. 1 Working of Stations 1-12 2 Working of Trains 13-14 3 Marshalling 15-18 4 Freight Operation 19-27 5 Preferential Schedule & Rationalization Order 28 6 Movement of ODC and Other Bulky Consignment 29-32 7 Control Organisation 33-44 8 Command, Control & Coordination of Emergency Rescue Operations on the open line 45-54 9 Marshalling Yards and Freight Terminals 55-67 10 Container Train Operation 68-72 11 Customer Interface and Role of Commercial Staff 73-77 12 Inspections 78-83 13 Interlocking 84-92 14 Station Working Rules and Temporary Working Order 93-102 15 Non-Interlocked Working of Station 103-114 16 Operating Statistics 115-121 17 FOIS 122-146 I.C.M.S - Module in ICMS - System - Data Feeding 147-148 - - MIS Reports 18 C.O.A 149 19 ACD 150 20 Derailment Investigation 151-158 21 Concept of Electric Traction 159-164 Crew link, loco link & power plant 165-166 Electric Loco maintenance schedule Diesel Loco maintenance schedule 167-169 Features of Electric Locomotives Brake power certificate 170 Various machines used for track maintenance 171 WORKING OF STATIONS (Back to Index) Railway Stations, world wide, are located in prime city centres, as railways were started at a time when expansion of cities was yet to start. Railway station continues to be the focal point of central business district in all cities in the world. All description of rail business is transacted at the station, passengers start journey or complete it, outward parcels are booked and inward parcel consignments received and kept ready for delivery. -

Fall 2011 $8.00 US

Fall 2011 Journal 44 $8.00 US Offi cial Publication of the Layout Design Special Interest Group, Inc. Features Sectional, Modular and Portable Layouts Sections Designed to Move – and Do! .....................4 by Doug Harding Modules for Home and Road .................................11 by Wolfgang Dudler, MMR Trenance: Compact English Terminus .................16 by Nigel Mann 4 Free-moN LDEs at X2011 West ..............................24 by Stephen Williams What Would you do Differently? .............................26 Ideas from Phil Gulley, Robert Hoffman, David Parks, Jim Providenza and Jim Radkey News and Departments New Ways to Help and Enjoy the SIG ......................3 by Seth Neumann, LDSIG President Taking it on the Road ..................................................3 by Byron Henderson 11 LDJ Questions, Comments and Corrections ..........31 Tulsa 2011: Exploring Design Ideas ........................32 by Dave Salamon 2012 Meeting Plans: Bay Area, CA; Tulsa, OK ......33 X2011W – Learning, Layouts and Outreach ...........34 16 Layout Design SIG Membership The Layout Design Special Dues*: $25.00 USD; Canada $25.00 Interest Group (LDSIG) is USD; Foreign $35.00 USD. Journal an independent, IRS 501(c) * One membership cycle includes four The Layout Design Journal (LDJ) is the (3) tax-exempt group af- issues of the Layout Design Journal. offi cial publication of the Layout Design fi liated with the National Please make checks payable to the “Lay- Special Interest Group, Inc. Model Railroad Association (NMRA). out Design SIG.” Canadian and Foreign Opinions The LDSIG’s goal is to act as a forum for payments must be drawn on a US bank, The opinions expressed in the LDJ are the members’ exchange of information paid using PayPal, or be via an interna- solely those of the original authors where and ideas, and to develop improved ways tional money order. -

The North Cornwall Line the LSWR Had Already Long Maintained a from Waterloo on 22Nd August 1964

BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:17 Page 4 SOUTHERN GONE WEST A busy scene at Halwill Junction on 31st August 1964. BR Class 4 4-6-0 No.75022 is approaching with the 8.48am from Padstow, THE NORTH CORNWALL while Class 4 2-6-4T No.80037 waits to shape of the ancient Bodmin & Wadebridge proceed with the 10.00 Okehampton–Padstow. BY DAVID THROWER Railway, of which more on another occasion. The diesel railcar is an arrival from Torrington. (Peter W. Gray) Followers of this series of articles have seen The purchase of the B&WR, deep in the heart how railways which were politically aligned of the Great Western Railway’s territory, acted he area served by the North Cornwall with the London & South Western Railway as psychological pressure upon the LSWR to line has always epitomised the progressively stretched out to grasp Barnstaple link the remainder of the system to it as part of Tcontradiction of trying to serve a and Ilfracombe, and then to reach Plymouth via a wider drive into central Cornwall to tap remote and sparsely-populated (by English Okehampton, with a branch to Holsworthy, the standards) area with a railway. It is no surprise latter eventually being extended to Bude. The Smile, please! A moorland sheep poses for the camera, oblivious to SR N Class 2-6-0 to introduce this portrait of the North Cornwall Holsworthy line included a station at a remote No.31846 heading west from Tresmeer with line by emphasising that railways mostly came spot, Halwill, which was to become the the Padstow coaches of the ‘Atlantic Coast very late to this part of Cornwall — and left junction for the final push into North Cornwall. -

Chapter 2: Traffic - Commercial and Operations

Chapter 2 Traffic – Commercial and Operations Chapter 2: Traffic - Commercial and Operations Traffic Department comprises two main streams – Commercial and Operations. The commercial department is responsible for marketing and sale of transportation provided by a railway, for developing traffic, improving quality of service provided to customers and regulating tariffs of passenger, freight and other coaching traffic and monitoring their collection, accountal and remittance. The Operating department is responsible for planning of transportation services – both long-term and short-term, managing day to day running of trains including their time tabling, ensuring availability and proper maintenance of rolling stock to meet the expected demand and conditions for safe running of trains. At the Railway Board level, the traffic department is headed by Member (Traffic), who is assisted by Additional Members/ Advisors. At the zonal level, the operating and commercial departments are headed by Chief Operations Manager (COM) and Chief Commercial Manager (CCM). At the divisional level, the operating and commercial departments are headed by Senior Divisional Operations Manager (Sr. DOM) and Senior Divisional Commercial Manager (Sr. DCM). The total expenditure of the Traffic Department during the year 2010-11 was `7,796.78 crore. During the year, apart from regular audit of vouchers and tenders etc., 856 offices of the department including 636 stations were inspected. This chapter includes four thematic studies conducted across Zonal Railways covering freight and passenger services, freight policy of enhanced loading and concessional tariffs. ¾ Up-Gradation of Goods Sheds - The study revealed that increase in rake turnover was hampered due to deficient planning and delays in implementation. -

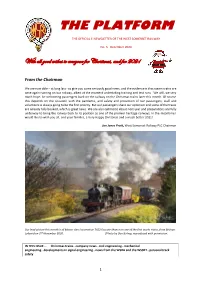

The Platform

THE PLATFORM THE OFFICIAL E-NEWSLETTER OF THE WEST SOMERSET RAILWAY No. 5 December 2020 With all good wishes to everyone for Christmas, and for 2021 From the Chairman We are now able – at long last - to give you some seriously good news, and the evidence is that steam trains are once again running on our railway, albeit at the moment undertaking training and test runs. We will, we very much hope, be welcoming passengers back on the railway on the Christmas trains later this month. Of course this depends on the situation with the pandemic, and safety and protection of our passengers, staff and volunteers is always going to be the first priority. But our passengers share our optimism and some of the trains are already fully booked, which is great news. We are also optimistic about next year and preparations are fully underway to bring the railway back to its position as one of the premier heritage railways. In the meantime I would like to wish you all, and your families, a Very Happy Christmas and a much better 2021! Jon Jones Pratt, West Somerset Railway PLC Chairman Our lead picture this month is of Manor class locomotive 7822 Foxcote Manor on one of the first works trains, from Bishops Lydeard on 2nd November 2020. [Photo by Don Bishop, reproduced with permission. IN THIS ISSUE…. Christmas trains…company news…civil engineering…mechanical engineering…developments in signal engineering…news from the WSRA and the WSSRT…personal track safety 1 Christmas Trains Trains have been operating from Bishops Lydeard to Williton and back over the last few weeks. -

Environment Management in Indian Railways

Environment Management in Indian Railways PREFACE This Report (No. 21 of 2012-13- Performance Audit for the year ended 31 March 2011) has been prepared for submission to the President under Article 151 (1) of the Constitution of India. The report contains results of the review of Environment Management in Indian Railways – Stations, Trains and Tracks. The observations included in this Report have been based on the findings of the test-audit conducted during 2011-12 as well as the results of audit conducted in earlier years, which could not be included in the previous Reports. i Environment Management in Indian Railways Abbreviations used in the Report IR Indian Railways CR Central Railway ER Eastern Railway ECR East Central Railway ECoR East Coast Railway NR Northern Railway NCR North Central Railway NER North Eastern Railway NFR Northeast Frontier Railway NWR North Western Railway SR Southern Railway SCR South Central Railway SER South Eastern Railway SECR South East Central Railway SWR South Western Railway WR Western Railway WCR West Central Railway RPU Railway Production Units i Environment Management in Indian Railways EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I Environment Management in Indian Railways Environment is a key survival issue and its challenges and significance have assumed greater importance in recent years. The National Environment Policy, 2006 articulated the idea that environmental protection shall form an integral part of the developmental process and cannot be considered in isolation. Indian Railways (IR) is the single largest carrier of freight and passengers in the country. It is a bulk carrier of several pollution intensive commodities like coal, iron ore, cement, fertilizers, petroleum etc. -

Castlemaine Goods Shed Heritage Assessment

Castlemaine Goods Shed Heritage assessment Final report 16 March 2011 Prepared for Mount Alexander Shire Context Pty Ltd Project Team: Louise Honman Georgia Bennett Report Register This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Castlemaine Goods Shed Draft Report undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Notes/description Issue date Issued to NoNoNo.No ... No. 1349 1 Draft report 11/2/11 Greg Anders 1349 2 Draft report 16/3/11 Fiona McMahon Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] Web www.contextpl.com.au ii CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IV Introduction 1 Purpose 1 Scope of work and limitations 1 Existing heritage status 2 State government 2 Local government 2 Contextual history 7 Establishment of Castlemaine 7 The Melbourne and River Murray Railway 7 Description 8 Castlemaine Railway Precinct 8 Goods Shed 8 Assessment of significance 9 Conservation objectives 10 Land use 10 Setting 10 New uses 10 Building fabric 11 Recommendations 11 REFERENCES 12 APPENDIX 1 13 Significance of the Bendigo Line 13 APPENDIX 2 15 Criteria for assessing cultural significance 15 iii CASTLEMAINE GOODS SHED EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report has been prepared for Mount Alexander Shire to inform Council of the cultural heritage significance of the Castlemaine Goods Shed. Set within the Railway Station precinct the Goods Shed is one element of several railway related structures that make up the State listed precinct. In previous research undertaken by Context as part of the Regional Rail Link Project (2005) it was established that the whole of the Bendigo line is significant at both the Local and State levels.