Know Your Rights: Free Speech, Protests & Demonstrations In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World

Boston College Law Review Volume 60 Issue 7 Article 6 10-30-2019 Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World Lauren E. Beausoleil Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Beausoleil, Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World, 60 B.C.L. Rev. 2100 (2019), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol60/iss7/6 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE, HATEFUL, AND POSTED: RETHINKING FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION OF HATE SPEECH IN A SOCIAL MEDIA WORLD Abstract: Speech is meant to be heard, and social media allows for exaggeration of that fact by providing a powerful means of dissemination of speech while also dis- torting one’s perception of the reach and acceptance of that speech. Engagement in online “hate speech” can interact with the unique characteristics of the Internet to influence users’ psychological processing in ways that promote violence and rein- force hateful sentiments. Because hate speech does not squarely fall within any of the categories excluded from First Amendment protection, the United States’ stance on hate speech is unique in that it protects it. -

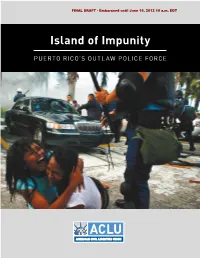

Island of Impunity

FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT J U N E 2012 Island of Impunity PUERTO RICO’S OUTLAW POLICE FORCE Island of Impunity: Puerto R ico’s ico’s O utlaw Police Force utlaw Police FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity PUERTO Rico’s OUTLAW POLICE FORCE JUNE 2012 FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity: Puerto Rico’s Outlaw Police Force June 2012 American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 www.aclu.org Cover Image: Betty Peña Peña and her 17-year-old daughter Eliza Ramos Peña were attacked by Riot Squad officers while they peacefully protested outside the Capitol Building. Police beat the mother and daughter with batons and pepper-sprayed them. Photo Credit: Ricardo Arduengo / AP (2010) FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Table of Contents Glossary of Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 7 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 11 II. Background: The Puerto Rico Police Department .................................................. 25 III. Shooting to Kill: Unjustified Use of Lethal Force ................................................... 31 a. Reported Killings of Civilians by the PRPD between 2007 and 2011 ......................33 b. Case Study: Miguel Cáceres Cruz ...........................................................................43 c. -

Politics in Action: Amending the Constitution Regory Lee Johnson Knew Little About the Constitution, but He Knew That He Was Upset

2 Listen to Chapter 2 on MyPoliSciLab The Constitution Politics in Action: Amending the Constitution regory Lee Johnson knew little about the Constitution, but he knew that he was upset. He felt that the buildup of nuclear weapons in the world threatened the planet’s survival, and he wanted to protest presidential and corporate policies G concerning nuclear weapons. Yet he had no money to hire a lobbyist or to pur- chase an ad in a newspaper. So he and some other demonstrators marched through the streets of Dallas, chanting political slogans and stopping at several corporate loca- tions to stage “die-ins” intended to dramatize the consequences of nuclear war. The demonstra- tion ended in front of Dallas City Hall, where Gregory doused an American flag with kerosene and set it on fire. Burning the flag violated the law, and Gregory was convicted of “desecration of a venerated object,” sentenced to one year in prison, and fined $2,000. He appealed his conviction, claiming that the law that prohibited burning the flag violated his freedom of speech. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed in the case of Texas v. Gregory Lee Johnson. Gregory was pleased with the Court’s decision, but he was nearly alone. The public howled its opposition to the decision, and President George H. W. Bush called for a constitutional amend- ment authorizing punishment of flag desecraters. Many public officials vowed to support the amendment, and organized opposition to it was scarce. However, an amendment to prohibit burn- ing the American flag did not obtain the two-thirds vote in each house of Congress necessary to send it to the states for ratification. -

Campus Free Speech: the First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU Campus Free Speech: The First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299 Mark Kunkel senior legislative attorney READING THE CONSTITUTION • November 2018, Volume 3, Number 2 © 2018 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. n November 16, 2016, conservative speaker Ben Shapiro prepared to deliver a speech at the University of Wisconsin–Madison called “Dismantling Safe Spac- es: Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings.” A registered student organization, the OUW–Madison chapter of Young Americans for Freedom, had invited Shapiro to speak. After he began to speak, “protesters lined up in front of the stage, their shouts about feel- ing at risk on campus drowned out by retorts from the audience. After some 10 minutes of chaos, the protesters filed out of the room, reportedly after being threatened with arrest by UW Police officers.”1 In February 2017, the University of California–Berkeley cancelled a speech by Milo Yiannopoulos, who had been invited to speak by the Berkeley College Republicans, after masked agitators interrupted an otherwise nonviolent protest and insti- gated a violent riot.2 On March 2, 2017, protesters disrupted a speech at Middlebury Col- lege in Vermont by controversial author, Charles Murray, who had been invited to speak by a student chapter of The American Enterprise Institute. -

Protecting National Flags: Must the United States Protect Corresp COMMENT

Phillips: Protecting National Flags: Must the United States Protect Corresp COMMENT PROTECTING NATIONAL FLAGS: MUST THE UNITED STATES PROTECT CORRESPONDING FOREIGN DIGNITY INTERESTS? INTRODUCTION On a summer day in 1984, Gregory Lee Johnson found his fif- teen minutes of fame. He burned an American flag outside the Re- publican National Convention in Dallas and was convicted of vio- lating a Texas statute that penalizes flag desecration.1 His conviction was eventually appealed to the United States Supreme Court.' The resulting June 21, 1989 decision, holding that his con- viction was unconstitutional, has been derided in the legal3 and popular4 press. Mr. Johnson would not have been prosecuted had he burned a foreign flag instead of the American flag, because no federal or state statute prohibits the desecration of a foreign flag.' He would not have been prosecuted under any legal theory, as shown by the 1. TEX. PENAL CODE ANN. § 42.09 (Vernon 1989) provides in full: Section 42.09 Desecration of Venerated Object (a) A person commits an offense if he intentionally or knowingly desecrates: (1) a public monument; (2) a place of worship or burial, or (3) a state or national flag. (b) For purposes of this section, 'desecrate' means deface, damage, or otherwise physically mistreat in a way that the actor knows will seriously offend one or more persons likely to observe or discover his action. (c) An offense in this section is a Class A misdemeanor. Subdivision (a)(3) was deleted by the 71st Legislature in 1989. The 71st Legislature added subdivision (d) which provides: "An offense under this section is a felony of the third degree if a place of worship or burial is desecrated." (Vernon 1990). -

Texas V. Johnson: the Constitutional Protection of Flag Desecration

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 17 Issue 3 Article 6 4-15-1990 Texas v. Johnson: The Constitutional Protection of Flag Desecration Patricia Lofton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Patricia Lofton Texas v. Johnson: The Constitutional Protection of Flag Desecration, 17 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (1990) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol17/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Texas v. Johnson: The Constitutional Protection of Flag Desecration I. INTRODUCTION On August 22, 1984, an American flag was flying in front of the Mercantile Bank building in Dallas, Texas. While Dallas was hosting the Republican National Convention, Gregory Lee Johnson and fel- low protesters were marching through the streets to challenge the policies of the Reagan Administration.1 Along the way, they spray painted buildings and staged "die-in's" to demonstrate the effect of a nuclear explosion.2 When the protestors arrived at the Mercantile Bank building, they bent down the flagpole and one of them removed the American flag from its pole and handed it to Johnson.3 The march continued to the Dallas City Hall where Johnson burned the flag while the protesters chanted "America, the -red, white, and blue, we. -

Download Download

Free Speech Zones: Silencing the Political Dissident Chris Demaske Following Sept. 11, 2001, the Bush Administration began impos- ing every increasing limitations on civil rights. One example is the implementation of free speech zones, a practice in which po- litical dissidents are cordoned off from the President during pub- lic appearances. While these zones originated in the 1980s, the use of them has grown considerably in the past few years. Critics argue that moving protesters to a remote location during Presi- dential events gives the impression that there is no dissent. This paper explores the constitutionality of free speech zones, ulti- mately demonstrating the shortcomings of the true threats doc- trine, a legal framework for analysis in cases dealing with speech that may be threatening. This article suggests an alternative framework for analysis that would 1) better balance national security interests with speech protection for political dissidents and 2) clear up some of the doctrinal confusion in the application of the true threats doctrine in general. irst Amendment scholars have shown us that historically anti-government political speech comes under attack by government officials more during wartime than peacetime.1 In the current U.S. climate created by the so- called “war on terror,” coupled with the physical war in Iraq, the political Fdissident again has become subject to speech restrictions. These infringements are far ranging – from issues of academic freedom to restriction of once public infor- mation to invasions of privacy. The need to find a balance between protecting na- tional security and protecting freedom of speech in this new climate requires that one think more complexly. -

Searching for Balance with Student Free Speech: Campus Speech Zones, Institutional Authority, and Legislative Prerogatives

SEARCHING FOR BALANCE WITH STUDENT FREE SPEECH: CAMPUS SPEECH ZONES, INSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY, AND LEGISLATIVE PREROGATIVES NEAL H. HUTCHENS* FRANK FERNANDEZ* INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 103 I. SOME COMMENTS ON AUTHORS’ POSITIONALITY ................................ 106 II. FORUM STANDARDS AND OPEN CAMPUS AREAS ................................ 109 III. STUDENTS, OPEN CAMPUS AREAS, AND SPEECH ZONES ................... 114 IV. BEYOND FORUM ANALYSIS ............................................................... 121 V. STATE LEGISLATIVE EFFORTS TO RE-SHAPE STUDENT AND INSTITUTIONAL SPEECH RIGHTS ................................................. 124 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 127 INTRODUCTION Free speech controversies on college and university campuses have resulted in a steady stream of media headlines.1 U.S. Attorney General Jeff * Professor of Higher Education at the University of Mississippi. The authors wish to thank the members of the Belmont Law Review for the opportunity to participate in this symposium issue. * Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Houston. 1. See, e.g., Nicholas B. Dirks, The Real Issue in the Campus Speech Debate: The University is Under Assault, WASH. POST (Aug. 9, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/ news/grade-point/wp/2017/08/09/the-real-issue-in-the-campus-speech-debate-the-university- is-under-assault/?utm_term=.1aa36d34d1bb (arguing -

Should the U.S. Enact a Flag Desecration Amendment?

LandmarkCases.org Texas v. Johnson / Should the U.S. Enact a Flag Desecration Amendment? Texas v. Johnson / Should the U.S. Enact a Flag Desecration Amendment? Directions: 1. Read the Background section below. 2. Complete the Flag Desecration Amendment section (page 3). Background Did you know that the proper method of destroying or “retiring” a flag that is worn out or soiled is to burn it? Boy Scouts and American Legion groups regularly perform such ceremonies. However, ordinary U.S. citizens who have burned flags for other reasons, such as political protest, have often been subject to arrest. Congress passed the Flag Protection Act in 1968 while some people were protesting against the Vietnam War. It was a national law that made it illegal to burn or treat the flag disrespectfully, which is called desecration. Many states also had laws that made flag burning illegal. In 1984, Gregory Lee Johnson was arrested for burning a flag during a protest outside the Republican National Convention in Texas. His case, Texas v. Johnson, eventually went to the Supreme Court of the United States. In the 5-4 ruling the Court explained that what Johnson did is a form of speech that is protected by the First Amendment making all flag desecration laws unconstitutional. Because of the Supreme Court’s decision in Texas v. Johnson, those who wanted to ban flag burning would have to amend the Constitution to make it happen. The most common path to enact a proposed constitutional amendment is proposal by two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures (see graphic on page 2). -

When Protest Is the Disaster: Constitutional Implications of State and Local Emergency Power

When Protest Is the Disaster: Constitutional Implications of State and Local Emergency Power Karen J. Pita Loor ABSTRACT The President’s use of emergency authority has recently ignited concern among civil rights groups over national executive emergency power. However, state and local emergency authority can also be dangerous and deserves similar attention. This article demonstrates that, just as we watch over the national executive, we must be wary of and check on state and local executives—and their emergency management law enforcement actors—when they react in crisis mode. This paper exposes and critiques state executives’ use of emergency power and emergency management mechanisms to suppress grassroots political activity and suggests avenues to counter that abuse. I choose to focus on the executive’s response to protest because this public activity is, at its core, an exercise of a constitutional right. The emergency management one- size-fits-all approach, however, does not differentiate between political activism, a flood, a terrorist attack, or a loose shooter. Public safety concerns overshadow any consideration of protestors’ individual rights. My goal is to interject liberty considerations into the executive’s calculus when it responds to political activism. I use the case studies of the 2016 North Dakota Access Pipeline protests, the 2014 Ferguson protests, and the 1999 Seattle WTO protests to demonstrate that state level emergency management laws and structures provide no realistic limit on the executive’s power, and the result is suppression of activists’ First and Fourth Amendment rights. Under current conditions, neither lawmakers nor courts realistically restrain the executive’s emergency management Karen J. -

Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks Patrick F

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Sociology Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011 Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks Patrick F. Gillham Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/sociology_facpubs Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Gillham, Patrick F., "Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks" (2011). Sociology. 12. https://cedar.wwu.edu/sociology_facpubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Social and Behavioral Sciences at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks1 Patrick F. Gillham [email protected] Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Idaho Moscow, ID Manuscript submitted for final review to Sociology Compass, April 2011 Abstract During the 1970s, the predominant strategy of protest policing shifted from “escalated force” and repression of protesters to one of “negotiated management” and mutual cooperation with protesters. Following the failures of negotiated management at the 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) demonstrations in Seattle, law enforcement quickly developed a new social control strategy, referred to here as “strategic incapacitation.” The U.S. police response to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks quickened the pace of police adoption of this new strategy, which emphasizes the goals of “securitizing society” and isolating or neutralizing the sources of potential disruption. -

Exceptions to the First Amendment

Order Code 95-815 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Updated July 29, 2004 Henry Cohen Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Summary The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press....” This language restricts government both more and less than it would if it were applied literally. It restricts government more in that it applies not only to Congress, but to all branches of the federal government, and to all branches of state and local government. It restricts government less in that it provides no protection to some types of speech and only limited protection to others. This report provides an overview of the major exceptions to the First Amendment — of the ways that the Supreme Court has interpreted the guarantee of freedom of speech and press to provide no protection or only limited protection for some types of speech. For example, the Court has decided that the First Amendment provides no protection to obscenity, child pornography, or speech that constitutes “advocacy of the use of force or of law violation ... where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” The Court has also decided that the First Amendment provides less than full protection to commercial speech, defamation (libel and slander), speech that may be harmful to children, speech broadcast on radio and television, and public employees’ speech.