When Protest Is the Disaster: Constitutional Implications of State and Local Emergency Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by PHIMC President and CEO Karen A. Reitan

Statement by PHIMC President and CEO Karen A. Reitan Friends: On May 14, we watched the jarring images of white men with automac weapons inside the Michigan State Capitol, nose to nose yelling at police with no response or consequence. Not two weeks later, we watched horrifying video of George Floyd, a black man, being murdered by a police officer kneeling on his neck in front of a crowd of onlookers begging him to stop. Three addional officers looked on and did nothing. This weekend, we watched thousands take to the streets calling for jusce with a righteous rage that began 400 years ago when the first Africans were stolen from their homes and brought here as slaves. That racism and oppression of people of color, parcularly black people, are a central component of American life cannot be disputed. It is imbedded in the United States at all levels - personal, professional, legal, spiritual - no maer where you turn, racism and oppression are there. The burden of dismantling the racist infrastructure of our country lies squarely with white people. We created this problem when we chose this path and it is ours to own and to change. We will never be the America we think we are until this happens. Racism is a public health crisis. That cannot be denied. Study aer study documents the disproporonate burden of chronic and infecous diseases among people of color. The chronic stress of being black in America, parcularly among women, has been shown to contribute to heart disease, hypertension, and premature death. In Chicago's wealthy and predominately white Streeterville community, residents live to be 90 on average, while nine miles south, in Chicago's impoverished and predominately black Englewood community, residents live only to 60. -

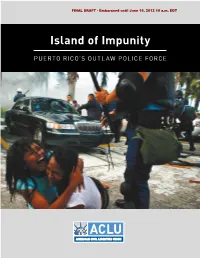

Island of Impunity

FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT J U N E 2012 Island of Impunity PUERTO RICO’S OUTLAW POLICE FORCE Island of Impunity: Puerto R ico’s ico’s O utlaw Police Force utlaw Police FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity PUERTO Rico’s OUTLAW POLICE FORCE JUNE 2012 FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity: Puerto Rico’s Outlaw Police Force June 2012 American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 www.aclu.org Cover Image: Betty Peña Peña and her 17-year-old daughter Eliza Ramos Peña were attacked by Riot Squad officers while they peacefully protested outside the Capitol Building. Police beat the mother and daughter with batons and pepper-sprayed them. Photo Credit: Ricardo Arduengo / AP (2010) FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Table of Contents Glossary of Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 7 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 11 II. Background: The Puerto Rico Police Department .................................................. 25 III. Shooting to Kill: Unjustified Use of Lethal Force ................................................... 31 a. Reported Killings of Civilians by the PRPD between 2007 and 2011 ......................33 b. Case Study: Miguel Cáceres Cruz ...........................................................................43 c. -

Campus Free Speech: the First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU Campus Free Speech: The First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299 Mark Kunkel senior legislative attorney READING THE CONSTITUTION • November 2018, Volume 3, Number 2 © 2018 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. n November 16, 2016, conservative speaker Ben Shapiro prepared to deliver a speech at the University of Wisconsin–Madison called “Dismantling Safe Spac- es: Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings.” A registered student organization, the OUW–Madison chapter of Young Americans for Freedom, had invited Shapiro to speak. After he began to speak, “protesters lined up in front of the stage, their shouts about feel- ing at risk on campus drowned out by retorts from the audience. After some 10 minutes of chaos, the protesters filed out of the room, reportedly after being threatened with arrest by UW Police officers.”1 In February 2017, the University of California–Berkeley cancelled a speech by Milo Yiannopoulos, who had been invited to speak by the Berkeley College Republicans, after masked agitators interrupted an otherwise nonviolent protest and insti- gated a violent riot.2 On March 2, 2017, protesters disrupted a speech at Middlebury Col- lege in Vermont by controversial author, Charles Murray, who had been invited to speak by a student chapter of The American Enterprise Institute. -

Resources to Facilitate Discussion About Race (With Special Thanks to Rabbi Melanie Aron)

Resources to Facilitate Discussion About Race (with special thanks to Rabbi Melanie Aron) Film: • Baltimore Rising (The impact of Freddie Gray) • Say Her Name: The Life and Death of Sandra Bland • Emanuel (The story of the Charleston shooting during bible study) • Just Mercy • Selma • 13th (Documentary which argues that present day mass incarceration is an extension of slavery based on the 13th amendment.) • Eyes On the Prize (Civil Rights Documentary Series) • I Am Not Your Negro (Documentary featuring James Baldwin) • When They See Us (The story of the Central Park 5) Books: • The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander • White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, Robin DiAngelo • How to Be an Anti-Racist, Ibram X. Kendi • Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing, Joy DeGruy Leary • I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, Austin Channing Brown • Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates • Waking Up White: and Finding Myself in The Story of Race, Debby Irving • America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America, Jim Wallis • White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, Karen Anderson • Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria: And Other Conversations About Race, Beverly Daniel Tatum • So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo • Stony the Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy and the Rise of Jim Crow, Henry Louis Gates • Eliminating Race-Based Mental Health Disparities: Promoting Equity and Culturally Responsive Care Across Settings, Monica T. -

August 2020 Nonfiction Highlights…

These books are coming soon! You can use this list to plan ahead and to search the library catalog. Visit our blog at www.thrall.org/BLB to explore even more books you might enjoy! Our librarians can help you find or reserve books! Upcoming Fiction Highlights… Universe of Two The Exiles I Give It to You by by by Valerie Martin Stephen P. Kiernan Christina Baker Kline “A timeless story of family, war, art, and A fictionalized account ”An ambitious, betrayal set around an “of Charlie Fisk, a gifted emotionally resonant ancient, ancestral home mathematician who was historical novel that in the Tuscan captures the hardship, drafted into Manhattan countryside from Project and ordered oppression, opportunity and hope of a trio of bestselling novelist against his morals to Valerie Martin.” build the detonator for women's lives.” the atomic bomb. With his musician wife, he spends his postwar life seeking redemption.” More Forthcoming Fiction… The Falcon Always Wings Twice - Donna Andrews Three Perfect Liars - Heidi Perks Someone to Romance - Mary Balogh Under Pressure - Robert Pobi Every Kind of Wicked - Lisa Black The Palace - Christopher Reich The Last Mrs. Summers - Rhys Bowen Say No More - Karen Rose Thick as Thieves - Sandra Brown The First to Lie - Hank Phillippi Ryan A Private Cathedral - James Lee Burke The Silent Wife - Karin Slaughter No Offense - Meg Cabot Royal - Danielle Steel Whirlwind - Janet Dailey The Deadline - Kiki Swinson The Lions of Fifth Avenue - Fiona Davis The Jackal - J.R. Ward The Wicked Sister - Karen Dionne Final Cut - S.J. Watson The Second Wife - Rebecca Fleet Seven Days in Summer - Marcia Willett A Lady's Guide to Mischief and Murder - Dianne Freeman The Weekend - Charlotte Wood Booked for Death - Victoria Gilbert Choppy Water - Stuart Woods Auntie Poldi and the Handsome Antonio - Mario Giordano The Night Swim - Megan Goldin Dead West - Matt Goldman Fiction Author Spotlight: Ron Rash Imperfect Women - Araminta Hall This storyteller writes contemporary or Sucker Punch - Laurell K. -

Download Download

Free Speech Zones: Silencing the Political Dissident Chris Demaske Following Sept. 11, 2001, the Bush Administration began impos- ing every increasing limitations on civil rights. One example is the implementation of free speech zones, a practice in which po- litical dissidents are cordoned off from the President during pub- lic appearances. While these zones originated in the 1980s, the use of them has grown considerably in the past few years. Critics argue that moving protesters to a remote location during Presi- dential events gives the impression that there is no dissent. This paper explores the constitutionality of free speech zones, ulti- mately demonstrating the shortcomings of the true threats doc- trine, a legal framework for analysis in cases dealing with speech that may be threatening. This article suggests an alternative framework for analysis that would 1) better balance national security interests with speech protection for political dissidents and 2) clear up some of the doctrinal confusion in the application of the true threats doctrine in general. irst Amendment scholars have shown us that historically anti-government political speech comes under attack by government officials more during wartime than peacetime.1 In the current U.S. climate created by the so- called “war on terror,” coupled with the physical war in Iraq, the political Fdissident again has become subject to speech restrictions. These infringements are far ranging – from issues of academic freedom to restriction of once public infor- mation to invasions of privacy. The need to find a balance between protecting na- tional security and protecting freedom of speech in this new climate requires that one think more complexly. -

Huddle up RACE & EQUITY TIP SHEETS FINAL

HOW TO HAVE COURAGEOUS CONVERSATIONS We have reached a clear People who are skilled at dialogue do their best to inflection point in our country’s make it safe for everyone to add their meaning to history of racism. The video-recorded murder of the shared pool - even ideas that at first glance George Floyd catalyzed a appear controversial, wrong, or at odds with their movement that demands a social justice reckoning the likes of own beliefs. Now, obviously they don't agree with which we have not seen before. ‘‘every idea; they simply do their best to ensure that Humans of all stripes are taking all ideas find their way into the open. to the streets, speaking out on social media, and pushing the Kerry Patterson / Crucial Conversations status quo to the breaking point. Your student-athletes are going to want to talk about it! HOW TO CREATE SPACE Conversations about racial justice and equity are difficult • LEADING with vulnerability and being willing to share but they are also critical, and your experience they can be transformative. We must create respectful space • LISTEN and encourage the group to listen to one another as well and opportunity for our young people to talk with us and with • ALLOW people time and space to share their each other. We must examine thoughts without interruption our own biases and do our own • ASK follow-up questions for clarity if necessary work before we can openly listen to our student-athletes, • SHARE what is valuable about someone’s question especially when they say things or comment we may not understand or • ACKNOWLEDGE that it is okay not to have all agree with. -

What Next? Why Now? an Interview with Karen Pittman February 1, 2021

What Next? Why Now? An Interview with Karen Pittman February 1, 2021 Ian Faigley (00:00): Good afternoon, everyone, on this sunny, actually snowy Monday in Washington, D.C. Thank you for joining us for today's Thought Leader Roundtable: A Conversation on Readiness. Today is a part of a regular series of explorations of the key questions of what does it mean for all young people to be ready for life's demands at every stage and what is it going to take to get there? For the past several years, Karen Pittman, our co-founder, president and CEO here at the Forum has signaled that the day was coming when she would step out of organizational leadership and find more time. Today is the day that she shifts gears, stepping out of the president and CEO role and becoming a senior fellow here at the Forum. Ian Faigley (00:43): To mark this occasion, we've asked Karen to shift from interviewer to interviewee, and we've asked Merita Irby, co-founder of the Forum and Karen's colleagues for more than 25 years to lead the discussion as Karen reflects on the paths taken and what's up next. We will be accepting questions and comments via the chat feature on today's session which is available at the bottom of your screen. There may be a few slides but the general focus will be on the conversation today. So please listen in and send in your questions as they come up. Lastly, today's session is being recorded. -

Searching for Balance with Student Free Speech: Campus Speech Zones, Institutional Authority, and Legislative Prerogatives

SEARCHING FOR BALANCE WITH STUDENT FREE SPEECH: CAMPUS SPEECH ZONES, INSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY, AND LEGISLATIVE PREROGATIVES NEAL H. HUTCHENS* FRANK FERNANDEZ* INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 103 I. SOME COMMENTS ON AUTHORS’ POSITIONALITY ................................ 106 II. FORUM STANDARDS AND OPEN CAMPUS AREAS ................................ 109 III. STUDENTS, OPEN CAMPUS AREAS, AND SPEECH ZONES ................... 114 IV. BEYOND FORUM ANALYSIS ............................................................... 121 V. STATE LEGISLATIVE EFFORTS TO RE-SHAPE STUDENT AND INSTITUTIONAL SPEECH RIGHTS ................................................. 124 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 127 INTRODUCTION Free speech controversies on college and university campuses have resulted in a steady stream of media headlines.1 U.S. Attorney General Jeff * Professor of Higher Education at the University of Mississippi. The authors wish to thank the members of the Belmont Law Review for the opportunity to participate in this symposium issue. * Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Houston. 1. See, e.g., Nicholas B. Dirks, The Real Issue in the Campus Speech Debate: The University is Under Assault, WASH. POST (Aug. 9, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/ news/grade-point/wp/2017/08/09/the-real-issue-in-the-campus-speech-debate-the-university- is-under-assault/?utm_term=.1aa36d34d1bb (arguing -

Fall Commencement Sunday, December 13, 2009 Two O’ Clock Colorado Convention Center

METROPOLITAN STATE COLLEGE of DENVER Fall ommencement C Sunday, December 13, 2009 Two O’ Clock Colorado Convention Center METROPOLITAN STATE COLLEGE of DENVER Program Contents Letter from the President .......... 3 Program ..................................... 4 Commencement Speaker .......... 5 Metro State: On the Road to Preeminence ...................... 6 Commencement Staff ............... 7 Retirees and In Memoriam ........ 7 Board of Trustees ...................... 7 Academic Attire ........................ 8 Academic Colors ....................... 9 Honor Societies ......................... 9 Fall 2009 Graduation Candidates ......... 10 Summer 2009 Graduates ........ 20 Seating Diagram ..................... 24 1 Dear member of the Summer or Fall 2009 graduating class: Congratulations on the successful completion of your hard-earned baccalaureate degree from Metropolitan State College of Denver. This is a significant achievement of which you and your family should be justifiably proud. Just as you now have a solid foundation on which to build a career or broaden your education in graduate school, Metro State has secured a strong heritage of academic excellence that will serve the Colorado community into the future. As a graduate of Metro State, you are now a part of that heritage, which includes more than 65,000 alumni, all of whom through their tenacity, energy and intelligence are having a significant impact on their community. Here are but a few examples of their achievements: • Kevin Vaughan (’86, journalism) has written for Colorado newspapers since 1989. Currently a writer for The Denver Post, he was a finalist for the 2008 Pulitzer Prize. • Tracie Keesee (’77, political science), a 20-year Denver Police Department veteran, was recently promoted to division chief of the department for technology and support. Keesee holds a doctorate from the University of Denver. -

South Carolina Black History Bugle – Issue 3

Book Review: HEART AND SOUL: The Story of America and African Americans Activism Education Literacy Music & the pursuit of Civil Rights I S Beacon of Hope, S A Light Out of Darkness U E T H R E E TO DREAM A BETTER WORLD The South Carolina Black History Bugle (SCBHB) is a Greetings Students, publication of the South Carolina Department of Education Welcome to the 2016 edition of The South Carolina developed by the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture. Black History Bugle! The theme of this issue is, “To averyinstitute.us Dream a Better World!” We want you to use the lessons of the past to fuel your vision for a better Editor-in-Chief tomorrow. This issue is full of historical information Patricia Williams Lessane, PhD about how American slavery impacted the lives of everyday Americans—regardless of their enslaved status—well after its BUGLE STAFF abolition in 1865. Yet even after slavery’s end, African Americans Deborah Wright have continued to face various forms of oppression, and at Associate Editor times, even violence. For example, here in South Carolina, student Daron Calhoun protestors known as the Friendship Nine and those involved in the Humanities Scholar Orangeburg Massacre faced legal persecution in their pursuit of Savannah Frierson civil rights. Then in June 2015, nine members of Emanuel African Copy Editor Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston were killed in a racist attack. South Carolinians from all walks of life came together GUEST CONTRIBUTORS to support the surviving members of Emanuel Church and the Celina Brown Charleston community at large. -

2020 Commencement Program.Pdf

Commencement MAY 2020 WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends: This is an occasion of profoundly mixed emotions for all of us. On one hand, there is the pride, excitement, and immeasurable hope that come with the culmination of years of effort and success at the University of Connecticut. But on the other hand, there is the recognition that this year is different. For the first time since 1914, the University of Connecticut is conferring its graduate and undergraduate degrees without our traditional ceremonies. It is my sincere hope that you see this moment as an opportunity rather than a misfortune. As the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus observed, “Difficulties show us who we are.” This year our University, our state, our nation, and indeed our world have faced unprecedented difficulties. And now, as you go onward to the next stage of your journey, you have the opportunity to show what you have become in your time at UConn. Remember that the purpose of higher education is not confined to academic achievement; it is also intended to draw from within those essential qualities that make each of us an engaged, fully-formed individual – and a good citizen. There is no higher title that can be conferred in this world, and I know each of you will exemplify it, every day. This is truly a special class that will go on to achieve great things. Among your classmates are the University’s first Rhodes Scholar, the largest number of Goldwater scholars in our history, and outstanding student leaders on issues from climate action to racial justice to mental health.