Restrictive Free Speech Zones and Student Speech Codes at Public Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island of Impunity

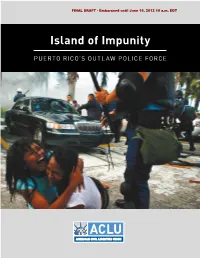

FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT J U N E 2012 Island of Impunity PUERTO RICO’S OUTLAW POLICE FORCE Island of Impunity: Puerto R ico’s ico’s O utlaw Police Force utlaw Police FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity PUERTO Rico’s OUTLAW POLICE FORCE JUNE 2012 FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Island of Impunity: Puerto Rico’s Outlaw Police Force June 2012 American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 www.aclu.org Cover Image: Betty Peña Peña and her 17-year-old daughter Eliza Ramos Peña were attacked by Riot Squad officers while they peacefully protested outside the Capitol Building. Police beat the mother and daughter with batons and pepper-sprayed them. Photo Credit: Ricardo Arduengo / AP (2010) FINAL DRAFT - Embargoed until June 19, 2012 10 a.m. EDT Table of Contents Glossary of Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 7 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 11 II. Background: The Puerto Rico Police Department .................................................. 25 III. Shooting to Kill: Unjustified Use of Lethal Force ................................................... 31 a. Reported Killings of Civilians by the PRPD between 2007 and 2011 ......................33 b. Case Study: Miguel Cáceres Cruz ...........................................................................43 c. -

Campus Free Speech: the First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299

LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU Campus Free Speech: The First Amendment and the Case of 2017 Assembly Bill 299 Mark Kunkel senior legislative attorney READING THE CONSTITUTION • November 2018, Volume 3, Number 2 © 2018 Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau One East Main Street, Suite 200, Madison, Wisconsin 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lrb • 608-504-5801 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. n November 16, 2016, conservative speaker Ben Shapiro prepared to deliver a speech at the University of Wisconsin–Madison called “Dismantling Safe Spac- es: Facts Don’t Care About Your Feelings.” A registered student organization, the OUW–Madison chapter of Young Americans for Freedom, had invited Shapiro to speak. After he began to speak, “protesters lined up in front of the stage, their shouts about feel- ing at risk on campus drowned out by retorts from the audience. After some 10 minutes of chaos, the protesters filed out of the room, reportedly after being threatened with arrest by UW Police officers.”1 In February 2017, the University of California–Berkeley cancelled a speech by Milo Yiannopoulos, who had been invited to speak by the Berkeley College Republicans, after masked agitators interrupted an otherwise nonviolent protest and insti- gated a violent riot.2 On March 2, 2017, protesters disrupted a speech at Middlebury Col- lege in Vermont by controversial author, Charles Murray, who had been invited to speak by a student chapter of The American Enterprise Institute. -

Download Download

Free Speech Zones: Silencing the Political Dissident Chris Demaske Following Sept. 11, 2001, the Bush Administration began impos- ing every increasing limitations on civil rights. One example is the implementation of free speech zones, a practice in which po- litical dissidents are cordoned off from the President during pub- lic appearances. While these zones originated in the 1980s, the use of them has grown considerably in the past few years. Critics argue that moving protesters to a remote location during Presi- dential events gives the impression that there is no dissent. This paper explores the constitutionality of free speech zones, ulti- mately demonstrating the shortcomings of the true threats doc- trine, a legal framework for analysis in cases dealing with speech that may be threatening. This article suggests an alternative framework for analysis that would 1) better balance national security interests with speech protection for political dissidents and 2) clear up some of the doctrinal confusion in the application of the true threats doctrine in general. irst Amendment scholars have shown us that historically anti-government political speech comes under attack by government officials more during wartime than peacetime.1 In the current U.S. climate created by the so- called “war on terror,” coupled with the physical war in Iraq, the political Fdissident again has become subject to speech restrictions. These infringements are far ranging – from issues of academic freedom to restriction of once public infor- mation to invasions of privacy. The need to find a balance between protecting na- tional security and protecting freedom of speech in this new climate requires that one think more complexly. -

Searching for Balance with Student Free Speech: Campus Speech Zones, Institutional Authority, and Legislative Prerogatives

SEARCHING FOR BALANCE WITH STUDENT FREE SPEECH: CAMPUS SPEECH ZONES, INSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY, AND LEGISLATIVE PREROGATIVES NEAL H. HUTCHENS* FRANK FERNANDEZ* INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 103 I. SOME COMMENTS ON AUTHORS’ POSITIONALITY ................................ 106 II. FORUM STANDARDS AND OPEN CAMPUS AREAS ................................ 109 III. STUDENTS, OPEN CAMPUS AREAS, AND SPEECH ZONES ................... 114 IV. BEYOND FORUM ANALYSIS ............................................................... 121 V. STATE LEGISLATIVE EFFORTS TO RE-SHAPE STUDENT AND INSTITUTIONAL SPEECH RIGHTS ................................................. 124 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 127 INTRODUCTION Free speech controversies on college and university campuses have resulted in a steady stream of media headlines.1 U.S. Attorney General Jeff * Professor of Higher Education at the University of Mississippi. The authors wish to thank the members of the Belmont Law Review for the opportunity to participate in this symposium issue. * Assistant Professor of Higher Education at the University of Houston. 1. See, e.g., Nicholas B. Dirks, The Real Issue in the Campus Speech Debate: The University is Under Assault, WASH. POST (Aug. 9, 2017), https://www.washingtonpost.com/ news/grade-point/wp/2017/08/09/the-real-issue-in-the-campus-speech-debate-the-university- is-under-assault/?utm_term=.1aa36d34d1bb (arguing -

When Protest Is the Disaster: Constitutional Implications of State and Local Emergency Power

When Protest Is the Disaster: Constitutional Implications of State and Local Emergency Power Karen J. Pita Loor ABSTRACT The President’s use of emergency authority has recently ignited concern among civil rights groups over national executive emergency power. However, state and local emergency authority can also be dangerous and deserves similar attention. This article demonstrates that, just as we watch over the national executive, we must be wary of and check on state and local executives—and their emergency management law enforcement actors—when they react in crisis mode. This paper exposes and critiques state executives’ use of emergency power and emergency management mechanisms to suppress grassroots political activity and suggests avenues to counter that abuse. I choose to focus on the executive’s response to protest because this public activity is, at its core, an exercise of a constitutional right. The emergency management one- size-fits-all approach, however, does not differentiate between political activism, a flood, a terrorist attack, or a loose shooter. Public safety concerns overshadow any consideration of protestors’ individual rights. My goal is to interject liberty considerations into the executive’s calculus when it responds to political activism. I use the case studies of the 2016 North Dakota Access Pipeline protests, the 2014 Ferguson protests, and the 1999 Seattle WTO protests to demonstrate that state level emergency management laws and structures provide no realistic limit on the executive’s power, and the result is suppression of activists’ First and Fourth Amendment rights. Under current conditions, neither lawmakers nor courts realistically restrain the executive’s emergency management Karen J. -

Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks Patrick F

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Sociology Social and Behavioral Sciences 2011 Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks Patrick F. Gillham Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/sociology_facpubs Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Gillham, Patrick F., "Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks" (2011). Sociology. 12. https://cedar.wwu.edu/sociology_facpubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Social and Behavioral Sciences at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Securitizing America: Strategic Incapacitation and the Policing of Protest Since the 11 September 2001 Terrorist Attacks1 Patrick F. Gillham [email protected] Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Idaho Moscow, ID Manuscript submitted for final review to Sociology Compass, April 2011 Abstract During the 1970s, the predominant strategy of protest policing shifted from “escalated force” and repression of protesters to one of “negotiated management” and mutual cooperation with protesters. Following the failures of negotiated management at the 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) demonstrations in Seattle, law enforcement quickly developed a new social control strategy, referred to here as “strategic incapacitation.” The U.S. police response to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks quickened the pace of police adoption of this new strategy, which emphasizes the goals of “securitizing society” and isolating or neutralizing the sources of potential disruption. -

The Assault on Free Speech, Public Assembly, and Dissent

A National Lawyers Guild Report 3 The Assault on Free Speech, Public Assembly, and Dissent A National Lawyers Guild Report on Government Violations of First Amendment Rights in the United States 2004 by Heidi Boghosian Foreword by Lewis Lapham The North River Press Additional copies can be obtained from your local bookstore or from the publisher: The North River Press Publishing Corporation P.O. Box 567 Great Barrington, MA 01230 (800) 486-2665 or (413) 528-0034 www.northriverpress.com ISBN # 0-88427-179-X A National Lawyers Guild Report 5 Contents Foreword Preface Introduction 7 The Imperiled First Amendment 12 Activities Protected by the First Amendment Attorney General Ashcroft’s Unlawful Failure to Prosecute Police Abuse The National Lawyers Guild’s Role in Defending Mass Movements How the Police, with Justice Department Approval, Violate the First Amendment 19 Chilling Political Expression Before Demonstrations 19 Intimidation by the Media Pretextual Searches and Raids of Organizing Spaces Police Infiltration and Surveillance Absent Allegations of Criminal Conduct Content-Based Exercise of Discretion in Denying Permits and in Paying for Permits and Liability Insurance Mass False Arrests and Detention Intimidation by FBI Questioning Criminalizing Political Expression at Demonstrations 43 Checkpoints Free-Speech Zones and the Secret Service Mass False Arrests and Detentions Snatch Squads Pop-Up Lines Containment Pens and Trap and Detain/Trap and Arrest Rush Tactic, Flanking, Using Vehicles as Weapons Crowd Control Using “Less Lethal” -

Foundation for Individual Rights in Education

No. 20-1066 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________________ ASHLYN HOGGARD, Petitioner, v. RON RHODES, ET AL., Respondents. _________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit _________________ BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FOUNDATION FOR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS IN EDUCATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _________________ Darpana Sheth Counsel of Record FOUNDATION FOR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS IN EDUCATION 700 Pennsylvania Ave., SE Washington, DC 20003 [email protected] (215) 717-3473 March 8, 2021 Counsel for Amicus Curiae i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether qualified immunity shields public-uni- versity officials from liability when the reasoning— but not the holding—of a binding decision gave the of- ficials fair warning they were violating the First Amendment. 2. What degree of factual similarity must exist be- tween a prior case and the case under review to overcome qualified immunity in the First Amendment context? 3. Whether public-university officials should be held to a higher standard than police officers and other on-the-ground enforcement officials for purposes of qualified immunity. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED ....................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................iv INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................................ 3 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 5 I. Under This Court’s Clear First Amendment Rulings, Courts Have Routinely Invalidated University Policies on Campus Expression. ....................................... 5 II. Most Public Colleges and Universities Still Maintain Policies That Infringe Students’ First Amendment Rights. ................... 9 A. Campus “Free Speech Zones” Turn the First Amendment on its Head. ............ 11 B. Sweeping and Vague Speech Policies Stifle Student Speech. -

Surveillance, Media and Police Militarization at Protests

THE DOMESTIC WAR ON TERROR: SURVEILLANCE, MEDIA AND POLICE MILITARIZATION AT PROTESTS by COLLEEN CARROLL MIHAL B.A., Virginia Tech, 2001 M.A., Virginia Tech, 2004 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Media, Communications, and Information 2015 This dissertation entitled: The Domestic War on Terror: Surveillance, Media, and Police Militarization at Protests written by Colleen Carroll Mihal has been approved for the College of Media, Communications, and Information Dr. Andrew Calabrese Dr. Janice Peck Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 0708.22 Mihal, Colleen Carroll (Ph.D., College of Media, Communications, and Information) The Domestic War on Terror: Surveillance, Media, and Police Militarization at Protests Dissertation directed by Professor Andrew Calabrese President George W. Bush and his administration reacted to the attacks on September 11, 2001 by declaring a “war on terrorism” and enacting policies that expanded executive power, restricted civil liberties, violated civil rights, and increased surveillance powers. These processes can be described as a state of exception (Agamben, 2005; Ericson, 2007; Scheppele, 2004). During a state of exception, it is believed, or at least proclaimed, that the exceptional nature of the times defies the ability of the normal legal order to cope with the crisis, requiring exceptional and extra-legal measures. Despite the centrality and indispensability of communication to a state of exception, the role of communication has received little in-depth scholarly analysis. -

How Free Speech Zones on College Campuses Advance Free Speech Values

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 10 Winter 2020 Saving the Space: How Free Speech Zones on College Campuses Advance Free Speech Values Troy Lange J.D. Candidate, 2020, Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Lange, Troy (2020) "Saving the Space: How Free Speech Zones on College Campuses Advance Free Speech Values," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol25/iss1/10 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Saving the Space: How Free Speech Zones on College Campuses Advance Free Speech Values Troy Lange* “The constitutional guarantee of liberty implies the existence of an organized society maintaining public order, without which liberty itself would be lost in the excesses of anarchy.” – Justice Arthur J. Goldberg1 INTRODUCTION On March 2nd, 2019, President Donald Trump announced his intention to issue an executive order that would force colleges to “guarantee” free speech rights for their students.2 On March 21st, the President did in fact issue an order to this effect.3 While there is likely no meaningful legal effect to the order, in that it only holds schools to standards to which they were already held,4 it is * J.D. -

Assessing Constitutional Challenges to University Free Speech Zones Under Public Forum Doctrine

Indiana Law Journal Volume 79 Issue 1 Article 6 Winter 2004 Assessing Constitutional Challenges to University Free Speech Zones Under Public Forum Doctrine Thomas J. Davis Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Thomas J. (2004) "Assessing Constitutional Challenges to University Free Speech Zones Under Public Forum Doctrine," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 79 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol79/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assessing Constitutional Challenges to University Free Speech Zones Under Public Forum Doctrine THOMAS J. DAVIS" TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................267 I. DEFINING THE FRAMEWORK ...............................................................................270 A . Public Forum Doctrine ..............................................................................270 B. The Archetype Case: Bayless v. Martine ...................................................272 II. THE UNIVERSITY AS A PUBLIC FORUM ..............................................................274 -

The Question of Speech on Private Campuses and the Answer Nobody Wants to Hear Steven P

Mitchell Hamline Law Review Volume 44 | Issue 2 Article 6 2018 The Question of Speech on Private Campuses and the Answer Nobody Wants to Hear Steven P. Aggergaard Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Aggergaard, Steven P. (2018) "The Question of Speech on Private Campuses and the Answer Nobody Wants to Hear," Mitchell Hamline Law Review: Vol. 44 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr/vol44/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mitchell Hamline Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Aggergaard: The Question of Speech on Private Campuses and the Answer Nobody THE QUESTION OF SPEECH ON PRIVATE CAMPUSES AND THE ANSWER NOBODY WANTS TO HEAR Steven P. Aggergaard† I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 629 II. WHERE WE ARE: THE STATUS OF CAMPUS SPEECH ............... 632 A. Current Law and Current Concerns ................................ 632 B. Special Rules for Sectarian Schools .................................. 637 C. Profiting from an Online Revolution ............................... 642 III. HOW WE GOT THERE: THE PERILOUS PATH FROM CHICKASAW TO ST. PAUL TO CHARLOTTESVILLE ...................................... 643 A. The Evolution of the State Action Doctrine ........................ 643 B. The Role of State Law in Filling a First Amendment Gap .... 650 C. From Stage Right, Enter the Statutes ................................ 654 IV.