This Item Is the Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tweemaandelijks Tijdschrift / Verschijnt Niet in Juli En Augustus / Januari-Februari 1977 West-Vlaanderen Werkt

westvlaanderen werkt 1.1977 tweemaandelijks tijdschrift / verschijnt niet in juli en augustus / januari-februari 1977 west-vlaanderen werkt I. 1977 WESTVLAAMS EKONOMISCH STUDIEBUREAU 19e JAARGANG Baron Ruzettelaan 33 8320 Brugge 4 Telefoon : 050/33 81 31 Postrekening 000-0125243-16 BTW : 408.382.668 Beschermkomitee Ridder P. van Outryve d’Ydewalie, inhoud Goeverneur, Voorzitter WER ; De Heer H. Smissaert, Ere-voorzitter Raad van Beheer WER ; 1 De heer P. Monballyu, In niemoriani Ir. J.M.L. Demeyere Voorzitter Raad van Beheer WER ; O. Vanneste De heren H. De Fauw, L. Gillon, A. Legein, H. Olivier, Mevrouw B. Platteau-Van Elslande, 2 Leden van de Bestendige Deputatie. Grensarbeiders in Noord-Frankrijk Redaktiekomitee J. Theys De Heren R. Annoot, L. Bockstaele, G. Declercq, P. Delafontaine, J. Pattyn, F. Van Damme, O. Vanneste. 10 Vijf jaar RMT maar 130 jaar Oostends bedrijf Redaktiesckretaris D. Sanders De Heer D. Sanders. 19 Redaktiesekretariaat en publiciteitsvoorwaarden Informatief : West-VIaanderen na de fusies WES, Baron Ruzettelaan 33, 8320 Brugge 4. van de gemeenten Abonnement 1976 : 170 fr. (BTW inbegrepen) 30 Postrekening 000-0125243-16 Spektrum WES, Baron Ruzettelaan 33, 8320 Brugge 4. De resultaten van de Belgische expansiewetgeving tussen 1959 en 1975 / Stand van de ruilverkaveling in West-VIaanderen / Nieuwe firma Purina Protein Europe investeert te leper op industriegebied / Richtlijn van toepassing op de hotelnijverheid in toeristische gebieden / Eerste Europese veerdienst met draagvleugelboot vanuit Zeebrugge / Wijziging in het huisvestingsbeleid van de provincie West-VIaanderen / Groen licht voor vervoercentrum LAR 42 Nieuwtjes Lay-out Johan Mahieu Drukkerij Groeninghe, Kortrijk Foto kaft Bij naamvermelding verschijnt de bijdrage onder de verantwoordelijkheid van de auteur. -

8E Bruggenloop Wijnendale - 27 Maart 2004 5,2 KM

8e Bruggenloop Wijnendale - 27 maart 2004 5,2 KM PL NR Naam Woonplaats CAT P/CAT Tijd GEM KM-Tijd 1 448 De Backer Frederik Waregem H 1 0:16:35 18,81 3:11 2 454 Bleyaert Bart Knesselare H 2 0:17:08 18,21 3:18 3 402 Bonte Gino Westrozebeke H 3 0:17:12 18,14 3:18 4 409 Depoorter Kenny Torhout H 4 0:17:18 18,03 3:20 5 453 Vandezande Johny Zonnebeke H 5 0:17:32 17,79 3:22 6 432 Vanhulle Francis Torhout H 6 0:18:47 16,61 3:37 7 427 Vandenbroucke Pieter Lichtervelde H 7 0:18:54 16,51 3:38 8 440 Joye Patrick Kortemark H 8 0:19:07 16,32 3:41 9 441 Haerinck Kris Zulte H 9 0:19:11 16,26 3:41 10 462 Gouwy Jordy Torhout H 10 0:19:20 16,14 3:43 11 422 Tempelaere Pascal Torhout H 11 0:19:33 15,96 3:46 12 452 Vandezande Stijn Zonnebeke H 12 0:19:49 15,74 3:49 13 407 Dedeyne Elke Torhout D 1 0:20:05 15,54 3:52 14 408 Deketelaere Annelies Torhout D 2 0:20:15 15,41 3:54 15 414 Leeuwerck Stephan Poperinge H 13 0:20:49 14,99 4:00 16 449 Sollenbier Richard Torhout H 14 0:20:52 14,95 4:01 17 419 Pollin Dries Torhout H 15 0:21:04 14,81 4:03 18 430 Vandewalle Marco Lichtervelde H 16 0:21:22 14,60 4:07 19 467 Dejonckheere Thierry Vlamertinge H 17 0:21:29 14,52 4:08 20 466 De Backer Roger Waregem H 18 0:21:52 14,27 4:12 21 431 Vandewalle Tania Lichtervelde D 3 0:22:03 14,15 4:14 22 429 Vandewalle Diego H 19 0:22:04 14,14 4:15 23 417 Pennynck Tiessa Roeselare D 4 0:22:24 13,93 4:18 24 472 Verlinde Bram Wingene H 20 0:22:56 13,60 4:25 25 423 Timmerman Veronique D 5 0:23:17 13,40 4:29 26 416 Neyens Kenny Torhout H 21 0:23:22 13,35 4:30 27 404 De Beer Dirk Torhout -

Jouw Maandelijks Infoblad 07-08/17 2 Voorwoord Voor Inhoud Woord

TITELTJE 1 DE PANNE LEEFT JOUW MAANDELIJKS INFOBLAD 07-08/17 2 VOORWOORD VOOR INHOUD WOORD Beste inwoner, 3 BE-ALERT: METEEN VERWITTIGD BIJ EEN NOODSITUATIE tweedeverblijver, bezoeker in onze 4-5 NAAR HET STRAND! gemeente, 6-8 VROEGER EN NU “Joepie, vakantie!” We horen het 9 NIEUW RESERVATIESYSTEEM weer overal zeggen, vooral door VOOR BELBUS studenten die na een harde examenperiode eindelijk 10 SAMEN VOOR MEER ‘oef’ kunnen zeggen. Ze kunnen nu weer 2 maanden TOEGANKELIJKE VOETPADEN lang genieten van vrije tijd, tijd met vrienden, optredens, workshops, wandelingen en uiteraard van zon, strand en 11 OMGAAN MET ONGEWENSTE zee. Want daarvoor moet je toch zeker in De Panne zijn! TELEFONISCHE OPROEPEN Jaar na jaar is een zomer in De Panne gevuld met 12-13 FLUID ROOTS DOOR RICCARDO BERGAMINI onvergetelijke momenten. Op de pagina's 6-8 kun je een aantal van die nostalgische momenten 14-15 STARTER IN DE KIJKER uit het verleden opnieuw beleven. Kijk dus zeker verder in deze De Panne Leeft. Of beter nog… Kom 16 FOTOWEDSTRIJD: MET JE TAS OP REIS tussen 5 augustus en 30 september langs in het 16 THE ART OF SHOPPING gemeentehuis en bezoek de tentoonstelling ‘Zomerse groeten uit het verleden’ met foto’s uit het rijke 17 NATUURWEETJE: DE KLEINE PIETERMAN archief van de website ‘WESTHOEK verbeeldt’. Niet alleen omwille van de toeristische drukte, maar 18 DE NACHTEGAAL ZOMERT zeker ook omwille van de milieuproblematiek wil 19 OOK JIJ WAS ERBIJ ik iedereen nog de tip geven om je vanaf nu zo veel mogelijk te voet of met de fiets te verplaatsen, en voor 20 IK GA OP VAKANTIE EN NEEM MEE… langere afstanden het openbaar vervoer te gebruiken. -

Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan West-Vlaanderen

Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan West-Vlaanderen 2002 Ruimtelijk West-Vlaanderen Structuurplan Provinciaal Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan West-Vlaanderen deel 1 tekst Ruimte Voor Verscheidenheid 1 Het Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan West-Vlaanderen (PRS-WV) is goedgekeurd bij Ministerieel Besluit van 6 maart 2002. Deze uitgave van het PRS-WV heeft, vergeleken met het goedgekeurde document, een aantal aanpassingen ondergaan om de leesbaarheid te verbeteren (zoals lay-out, taalcorrecties, kleurkaarten). De inhoudelijke betekenis is niet gewijzigd. Deze publicatie bestaat uit twee delen, een tekstdeel (deel 1) en een kaartenbijlage (deel 2), terwijl dit voordien één boekdeel was. Dit document is het tekstdeel (deel 1). Het Ministerieel Besluit van 6 maart 2002 houdende goedkeuring van het PRS-WV, wordt als bijlage van het tekstdeel weergegeven. Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan West-Vlaanderen Voorwoord Op 12 juni 2001 keurde de Provincieraad van West-Vlaanderen het Provinciaal Ruimtelijk Structuurplan (PRS) goed, bijna 1 jaar na de goedkeuring van het Ontwerp PRS. In die tussenperiode kreeg het grote publiek de mogelijkheid om bezwaren, opmerkingen en suggesties te doen omtrent dit ontwerp.Tijdens het openbaar onderzoek maakten meer dan 3000 instanties schriftelijk hun commentaar over. Zowel gemeentebesturen, administraties, verenigingen als particulieren droegen hun steentje bij. De Regionale Commissie van Advies onderzocht deze com- mentaren en gaf daaromtrent een omstandig advies. Op basis van dit advies paste het Provincie- bestuur het Ontwerp PRS op heel wat punten aan. In het najaar van 2001 werden in functie van het in overeenstemming brengen met het Ruimtelijk Structuurplan Vlaanderen en terug op basis van bezwaren uitgebracht tijdens het openbaar onder- zoek, opnieuw aanpassingen aan het PRS aangebracht. -

July 20, 2019 Northwestern College Alumni Bike Tour Dunkirk to Haarlem

1 2 2 The Netherlands Northwestern College In 1998, Eurotrail organized its first bike tour for Northwestern College Alumni Bike Tour alumni. This tenth tour will take us from the beaches of Dunkirk through the battle fields of the First World War in Flanders and picturesque merchant dunkirk to haarlem towns in Belgium like Bruges to the province of Zeeland, where Delta Works and dikes keep the water out of the Low Countries, to Dordrecht, Gouda and Haarlem. We will bike through beautiful a varied landscape, on flat and quiet country roads or biking paths, pausing at castles, nature areas, historical cities July 6 - July 20, 2019 and quaint villages. On some evenings we will enjoy lectures on the history of the Low Countries. In this all-inclusive tour, you will be spoiled with gourmet food, excursions and cultural experiences. Comments from participants on other tours: “Twelve days of joy, education, variety, fun, friendship and excellent, caring leadership make this the tour of a lifetime!” “It has been an outstanding tour!! We have had a marvelous time and have learned so much! Every day was packed with great things!” “Thank you for a totally awesome time! Every day was a delight! We were treated like Royalty!” CONTENTS Daily itinerary 3-4 Tour leaders 3 SIOUXLAND TRAVEL Hotels and food 3 110 Central Ave. NW Orange City, IA 51041 Price 4 (712) 737-3777 1-800-882-5777 Reservation form 5 [email protected] www.siouxlandtravel.net Terms and conditions 6-7 3 4 4 Daily Itinerary 3 We will visit Sluis and cycle along the North Sea coast, taking the ferry to Vlissingen. -

London and Beyond Essays in Honour of Derek Keene

London and beyond Essays in honour of Derek Keene Edited by Matthew Davies and James A. Galloway London and beyond Essays in honour of Derek Keene London and beyond Essays in honour of Derek Keene Edited by Matthew Davies and James A. Galloway LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2012. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 44 5 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 70 4 (hardback edition) Contents Preface vii List of contributors xi List of gures xv List of tables xvii I. Markets, hinterlands and environments 1. Feeding another city: provisioning Dublin in the later middle ages Margaret Murphy 2. Did peasants need markets and towns? e experience of late medieval England Christopher Dyer 3. e proliferation of markets revisited Richard Britnell 4. ‘Tempests of weather and great abundance of water’: the ooding of the Barking marshes in the later middle ages James A. Galloway II. Luxury, innovation and skill 5. A taste for the Orient? Cosmopolitan demand for ‘exotic’ durable consumables in late medieval Bruges Peter Stabel 6. Hartlib’s world Rob Ilie 7. Hiding in the forest … e Gilberts’ rural scientic instrument manufactory Anita McConnell v London and beyond III. Suburbs, neighbourhoods and communities 8. -

Raad Van Bestuur Beslissingen

RAAD VAN BESTUUR BESLISSINGEN 18 NOVEMBER 2020 Digitale beraadslaging en stemming VERSLAG 2020/XVII A = AANWEZIG VO = VERONTSCHULDIGD AFW = AFWEZIG NAAM FUNCTIE AANDELEN STATUS Kris Declercq voorzitter A A Kurt Claeys ondervoorzitter A A Peter Roose ondervoorzitter A A Jurgen Content bestuurslid A A Dirk De fauw bestuurslid A A Gauthier Defreyne bestuurslid A A Christof Dejaegher bestuurslid A A Rita Demaré bestuurslid A A Ann-Sophie Himpe bestuurslid A A Katrien Desomer adviserend A A Justine Hollevoet adviserend A A Caroline Maertens bestuurslid A A Geert Van Tieghem adviserend A A Toon Vancoillie bestuurslid A A Ingrid Vandepitte bestuurslid A A Luc Vannieuwenhuyze bestuurslid A A Sandy Vanparys bestuurslid A A Dirk Verwilst bestuurslid A A Geert Sanders algemeen directeur A Patrick Zutterman directeur A 1 GOEDKEURING VERSLAG VORIGE RAAD VAN BESTUUR WONEN aankopen Bevestigd: - Langemark-Poelkapelle project Poelkapellestraat Gemeente Langemark-Poelkapelle Kennisneming: - stand van de aankopen van gronden in 2020 uitrustingswerken 2.1 vorderingsstaten, facturen en erelonen Goedgekeurd: Poperinge – Appelgoedje – omgevingswerken, vorderingsstaat 8 2.2 overname - Knokke-Heist project Heulebrug fase 1 – aanleg Kraaiennestplein Proces-verbaal van voorlopige overname dd. 22-10-2020 betreffende het uitvoeren van omgevingswerken en vrijgave van de helft van de gewone borgtocht en aanvullende borgtocht goedgekeurd - Zedelgem (Aartrijke) project Oude Trambedding Proces-verbaal van voorlopige overname dd. 30-11-2017 betreffende het uitvoeren van -

BJE 88 2019 Lock.Pdf

Belgian Journal of Entomology 88: 1–28 (2019) ISSN: 2295-0214 www.srbe-kbve.be urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:AD19BBD2-CD8C-4189-8820-A08FAABD6945 Belgian Journal of Entomology Fifty leafhoppers new to Belgium (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) Koen LOCK Merelstraat 27, B-9000 Gent (e-mail: [email protected]) Published: Brussels, July 23, 2019 Citation: LOCK K., 2019. - Fifty leafhoppers new to Belgium (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Belgian Journal of Entomology, 88: 1–28. ISSN: 1374-5514 (Print Edition) ISSN: 2295-0214 (Online Edition) The Belgian Journal of Entomology is published by the Royal Belgian Society of Entomology, a non-profit association established on April 9, 1855. Head office: Vautier street 29, B-1000 Brussels. The publications of the Society are partly sponsored by the University Foundation of Belgium. In compliance with Article 8.6 of the ICZN, printed versions of all papers are deposited in the following libraries: - Royal Library of Belgium, Boulevard de l’Empereur 4, B-1000 Brussels. - Library of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Vautier street 29, B-1000 Brussels. - American Museum of Natural History Library, Central Park West at 79th street, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA. - Central library of the Museum national d’Histoire naturelle, rue Geoffroy Saint- Hilaire 38, F-75005 Paris, France. - Library of the Muséum d’Histoire naturelle de Genève, route de Malagnou 1, CH-1208 Genève, Suisse. - Zoological Record, Thomson Reuters, Publication Processing, 1500 Spring Garden Street, Fourth Floor, Philadelphia PA 19130, USA. Front cover: Iassus scutellaris (Fieber, 1868), lateral view (photo by Koen Lock). 2 Belgian Journal of Entomology 88: 1–28 (2019) Fifty leafhoppers new to Belgium (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) Koen LOCK Merelstraat 27, B-9000 Gent (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract Leafhoppers or Cicadellidae are the largest family of the Auchenorrhyncha in Belgium, however, this family did not yet receive a lot of attention. -

74 Bus Dienstrooster & Lijnroutekaart

74 bus dienstrooster & lijnkaart 74 Brugge - Torhout - Lichtervelde - Roeselare Bekijken In Websitemodus De 74 buslijn (Brugge - Torhout - Lichtervelde - Roeselare) heeft 8 routes. Op werkdagen zijn de diensturen: (1) Brugge Station Perron 6: 05:13 - 18:40 (2) Lichtervelde Station Achterkant: 15:57 - 19:57 (3) Roeselare Station Perron 5: 06:25 - 19:01 (4) Rumbeke Sterrebos: 06:43 (5) Torhout Station Perron 2: 17:10 (6) Torhout Station Perron 3: 07:29 - 16:27 (7) Veldegem Steenovenstraat: 16:15 - 17:15 (8) Zedelgem Dorp: 17:03 Gebruik de Moovit-app om de dichtstbijzijnde 74 bushalte te vinden en na te gaan wanneer de volgende 74 bus aankomt. Richting: Brugge Station Perron 6 74 bus Dienstrooster 67 haltes Brugge Station Perron 6 Dienstrooster Route: BEKIJK LIJNDIENSTROOSTER maandag 05:13 - 18:40 dinsdag 05:13 - 18:40 Rumbeke Sterrebos 139 Kasteelstraat, Roeselare woensdag 05:13 - 18:40 Roeselare Sint-Elooisplein donderdag 05:13 - 18:40 134 Zuidmolenstraat, Roeselare vrijdag 05:13 - 18:40 Roeselare Residentie Flora zaterdag 07:01 - 18:11 83 Koning Albert I-laan, Roeselare zondag Niet Operationeel Roeselare De Mandel Koning Albert I-laan, Roeselare Roeselare Station Perron 5 Ardooisesteenweg, Roeselare 74 bus Info Route: Brugge Station Perron 6 Roeselare De Coninckplein Haltes: 67 88 Sint-Amandsstraat, Roeselare Ritduur: 89 min Samenvatting Lijn: Rumbeke Sterrebos, Roeselare Roeselare A. Willaertstraat Sint-Elooisplein, Roeselare Residentie Flora, 89 Hugo Verrieststraat, Roeselare Roeselare De Mandel, Roeselare Station Perron 5, Roeselare -

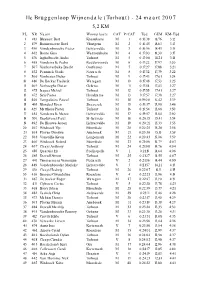

11E Bruggenloop Wijnendale (Torhout)

11e Bruggenloop Wijnendale (Torhout) - 24 maart 2007 5,2 KM PL NR Naam Woonplaats CAT P/CAT Tijd GEM KM-Tijd 1 483 Bleyaert Bart Knesselaere M 1 0:16:38 18,76 3:12 2 479 Boussemaere Roel Vlissegem M 2 0:16:45 18,63 3:13 3 450 Vandenbroucke Pieter Lichtervelde M 3 0:16:56 18,43 3:15 4 462 Bonte Gino Westrozebeke M 4 0:17:03 18,30 3:17 5 476 Inghelbrecht Andre Torhout M 5 0:17:08 18,21 3:18 6 455 Vandewalle Pedro Ruddervoorde M 6 0:17:22 17,97 3:20 7 507 Vanhaverbeke Brecht Oostkamp M 7 0:17:27 17,88 3:21 8 432 Penninck Gerdi Nazareth M 8 0:17:32 17,79 3:22 9 506 Vanbesien Didier Torhout M 9 0:17:43 17,61 3:24 10 486 De Backer Frederik Waregem M 10 0:17:48 17,53 3:25 11 509 Verhaeghe Dieter Geluwe M 11 0:17:54 17,43 3:27 12 475 Jaques Michiel Torhout M 12 0:17:55 17,41 3:27 13 472 Seys Pieter Handzame M 13 0:17:57 17,38 3:27 14 440 Tempelaere Pascal Torhout M 14 0:19:00 16,42 3:39 15 481 Blondeel Koen Zwevezele M 15 0:19:37 15,90 3:46 16 429 Mattheus Pieter Torhout M 16 0:19:54 15,68 3:50 17 454 Vandewalle Marco Lichtervelde M 17 0:19:57 15,64 3:50 18 501 Depluverez Paul St-Sauveur M 18 0:20:15 15,41 3:54 19 492 De Blauwe Jeroen Lichtervelde M 19 0:20:21 15,33 3:55 20 467 Witdouck Tijs Moorslede M 20 0:20:25 15,28 3:56 21 504 Plovier Dimitrie Assebroek M 21 0:20:36 15,15 3:58 22 508 Vancoillie Kevin Langemark M 22 0:20:43 15,06 3:59 23 466 Witdouck Roland Moorslede M 23 0:21:06 14,79 4:03 24 407 Claeys Anthony Torhout M 24 0:21:08 14,76 4:04 25 488 Quartier Els Poelkapelle V 1 0:21:19 14,64 4:06 26 485 Dewulf Simon Torhout M 25 0:21:27 -

PDF Van Tekst

Biekorf. Jaargang 53 bron Biekorf. Jaargang 53. A. Van Poelvoorde, Brugge 1952 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_bie001195201_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl i.s.m. 1 [Nummer 1] De legende van Pitgam DAT jaar was 't een buitengewone harde winter. 't Begoste te vriezen op Sinte-Cathriene, en Paschen stond voor de deure en 't vroos nog. Maar nog nooit sedert mensengeheugenis was 't zo bijtende koud geweest lijk daags voor Kerstdag. In één nacht vroos het happesteerte dikke, en men reed met peerden en wagens over de toegevrozen Colme lijk over een schurevloer. En maar altijd voort kwam de ijzigkoude wind uit het zeegat als een speie gebezen over de blote landstreek. Pietje Plaete, een oude eenzate. zat in den hoek van den heerd van zijn kavane zonder vier noch vonke, ineengekrompen te ruttelen van de koude. Zijn laatste brijzeltje brandinge was allange door de schouwe gevlogen, en hij stond bovendien zonder een mompe teten, verlaten van God en van de mensen. Er moest van entwaar hulpe komen of 't was gedaan met Pietje. Zo 't was Kerstavond en de klokken gingen aan 't luiden voor de nachtmesse. En Pietje hoorde die klokken en 't kwam hem te binnen van die vorige Kerstmesse, hij was er naartoe geweest: 't was daar goed Biekorf. Jaargang 53 2 en warm in die volle kerke, en er brandden veel keersen overal rond. En zo kwam het dat Pietje, over dat't ging, rechte ravelde en door den donkeren weg optrok naar de kerke van Hillegam. Goen' nacht, Petrus! klonk het daar, als hij op het kerkeplein aanlandde. -

Detailonderzoek Naar Onbenutte Bedrijfsgronden in West-Vlaanderen

DETAILONDERZOEK NAAR ONBENUTTE BEDRIJFSGRONDEN IN WEST-VLAANDEREN POM West-Vlaanderen - Provinciehuis Olympia - Koning Leopold III-laan 66 - 8200 Sint-Andries/Brugge Tel.: ../32/50/40 31 66 -Fax: ../32/50/71 94 06- E-mail: [email protected] – Website: www.pomwvl.be De Provinciale Ontwikkelingsmaatschappij is een publiekrechtelijke instelling met rechtspersoonlijkheid erkend door de Vlaamse Regering Detailonderzoek naar onbenutte bedrijfsgronden in West-Vlaanderen INHOUDSTAFEL Blz. INLEIDING ................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Methodologie van het detailonderzoek .................................................................................... 2 1.1. Inventarisatiefase................................................................................................................. 2 1.1.1 Vastleggen van het aantal te onderzoeken onbenutte bedrijfsgronden en het studiegebied ............................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2 Opmaak van een werkbare strategie ............................................................................ 5 1.1.3 Verzamelen van eigenaarsgegevens............................................................................ 5 1.1.4 Contactname met terreinbeheerders ............................................................................ 6 1.1.5 Het terreinonderzoek en de bevraging van de eigenaars ..............................................