Monks & the Middle Ages Information Sheets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Anderson, Known on the Trail As Mendorider, Is

More than 46,000 miles on horseback... and counting By Susan Bates d Anderson, known on the trail as MendoRider, is – and suffering – but, of course, unwilling to admit it. By the end of one of the few elite horsemen who have safely com- the ride, the hair on the inside of his legs had been painfully pulled pleted the PCT on horseback. On his return from every and rolled into little black balls. His skin was rubbed raw. He decided outing, his horses were healthy and well-fed and had that other than his own two legs and feet, the only transportation for been untroubled by either colic or injuries. him had to have either wheels or a sail. Jereen E Ed’s backcountry experience began in 1952 while he was still in Ed and his wife, , once made ambitious plans to sail high school, and by 1957 he had hiked the John Muir Trail section around the world. But the reality of financial issues halted their aspi- of the PCT. He continued to build on that experience by hiking rations to purchase a suitable boat. They choose a more affordable and climbing in much of the wilderness surrounding the PCT in option: they would travel and live in a Volkswagen camper. California. He usually went alone. Ed didn’t like any of the VW conversions then available on either Ed was, and is, most “at home” and comfortable in the wilderness side of the Atlantic, so, he designed and built his own. He envisioned – more so than at any other time or in any other place. -

The Sami and the Inupiat Finding Common Grounds in a New World

The Sami and the Inupiat Finding common grounds in a new world SVF3903 Kristine Nyborg Master of Philosophy in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Department of Archaeology and Social Anthropology University of Tromsø Spring 2010 2 Thank you To all my informants for helping me make this project happen and for taking me into your lives and sharing all your wonderful thoughts. I am extremely grateful you went on this journey with me. A special warm thanks to my main informant who took me in and guided the way. This would have been impossible without you, and your great spirits and laughter filled my thoughts as I was getting through this process. To supervisor, Bjørn Arntsen, for keeping me on track and being so supportive. And making a mean cup of latte. To National Park Service for helping me with housing. A special thanks to the Center for Sami Studies Strategy Fund for financial support. 3 Abstract This thesis is about the meeting of two indigenous cultures, the Sami and the Inupiat, on the Alaskan tundra more than a hundred years ago. The Sami were brought over by the U.S. government to train the Inupiat in reindeer herding. It is about their adjustment to each other and to the rapidly modernizing world they found themselves a part of, until the term indigenous became a part of everyday speech forty years ago. During this process they gained new identities while holding on to their indigenous ones, keeping a close tie to nature along the way. -

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-Playing Games

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-playing Games Throughout the Middle Ages the horse was a powerful symbol of social differences but also a tool for the farmer, merchant and fighting classes. While the species varied considerably, as did their names, here is a summary of the main types encountered across Medieval Europe. Great Horse - largest (15-16 hands) and heaviest (1.5-2t) of horses, these giants were the only ones capable of bearing a knight in full plate armour. However such horses lacked speed and endurance. Thus they were usually reserved for tourneys and jousts. Modern equivalent would be a «shire horse». Mules - commonly used as a beast of burden (to carry heavy loads or pull wagons) but also occasionally as a mount. As mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses, they were particularly useful for strenuous support tasks, such as hauling supplies over difficult terrain. Hobby – a tall (13-14 hands) but lightweight horse which is quick and agile. Developed in Ireland from Spanish or Libyan (Barb) bloodstock. This type of quick and agile horse was popular for skirmishing, and was often ridden by light cavalry. Apparently capable of covering 60-70 miles a single day. Sumpter or packhorse - a small but heavier horse with excellent endurance. Used to carry baggage, this horse could be ridden albeit uncomfortably. The modern equivalent would be a “cob” (2-3 mark?). Rouncy - a smaller and well-rounded horse that was both good for riding and carrying baggage. Its widespread availability ensured it remained relatively affordable (10-20 marks?) compared to other types of steed. -

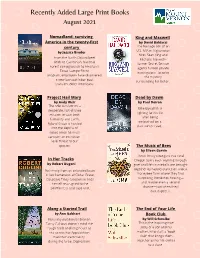

July Recently Added Large Print

Recently Added Large Print Books August 2021 Nomadland: surviving King and Maxwell America in the twenty-first by David Baldacci The teenage son of an century U.S. MIA in Afghanistan by Jessica Bruder hires Sean King and From the North Dakota beet Michelle Maxwell-- fields to California's National former Secret Service Forest campgrounds to Amazon's agents turned private Texas CamperForce investigators--to solve program, employers have discovered the mystery a new low-cost labor pool: surrounding his father. transient older Americans. Project Hail Mary Dead by Dawn by Andy Weir by Paul Doiron The sole survivor on a Mike Bowditch is desperate, last-chance fighting for his life mission to save both after being humanity and Earth, ambushed on a Ryland Grace is hurtled dark winter road, into the depths of space when he must conquer an extinction- level threat to our species. The Music of Bees by Eileen Garvin Three lonely strangers in a rural In Her Tracks Oregon town, each working through by Robert Dugoni grief and life's curveballs are brought Returning from an extended leave together by happenstance on a local in her hometown of Cedar Grove, honeybee farm where they find Detective Tracy Crosswhite finds surprising friendship, healing— herself reassigned to the and maybe even a second Seattle PD's cold case unit. chance—just when they l east expect it. Along a Storied Trail The End of Your Life by Ann Gabhart Book Club Kentucky packhorse librarian by Will Schwalbe Tansy Calhoun doesn't mind the This is the inspiring true rough trails and long hours as story of a son and his she serves her Appalachian mother, who start a "book mountain community club" that brings them during the Great Depression. -

North West Yorkshire Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Volume II: Technical Report

North West Yorkshire Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Volume II: Technical Report FINAL Report July 2010 Harrogate Borough Council with Craven District Council and Richmondshire District Council North West Yorkshire Level 1 SFRA Volume II: Technical Report FINAL Report July 2010 Harrogate Borough Council Council Office Crescent Gardens Harrogate North Yorkshire HG1 2SG JBA Office JBA Consulting The Brew House Wilderspool Park Greenall's Avenue Warrington WA4 6HL JBA Project Manager Judith Stunell Revision History Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to Initial Draft: Initial DRAFT report Linda Marfitt 1 copy of report 9th October 2009 by email (4 copies of report, maps and Sequential Testing Spreadsheet on CD) Includes review comments from Linda Marfitt (HBC), Linda Marfitt (HBC), Sian John Hiles (RDC), Sam Watson (CDC), John Hiles Kipling and Dan Normandale (RDC) and Dan Normandale FINAL report (EA). (EA) - 1 copy of reports, Floodzones for Ripon and maps and sequential test Pateley Bridge updated to spreadsheet on CD) version 3.16. FINAL report FINAL report with all Linda Marfitt (HBC) - 1 copy 9th July 2010 comments addressed of reports on CD, Sian Watson (CDC), John Hiles (RDC) and Dan Normandale (EA) - 1 printed copy of reports and maps FINAL Report FINAL report with all Printed copy of report for Linda 28th July 2010 comments addressed Marfitt, Sian Watson and John Hiles. Maps on CD Contract This report describes work commissioned by Harrogate Borough Council, on behalf of Harrogate Borough Council, Craven District Council and Richmondshire District Council by a letter dated 01/04/2009. Harrogate Borough Council‟s representative for the contract was Linda Marfitt. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Leader, 24/10/2018 09:30

Public Document Pack LEADER AGENDA DATE: Wednesday, 24 October 2018 TIME: 9.30 am VENUE: Meeting Room (TBC) - Civic Centre, St Luke's Avenue, Harrogate, HG1 2AE MEMBERSHIP: Councillor Richard Cooper (Leader) 1. Community Defibrillator Scheme Endorsement 2018: 1 - 20 To consider the written report submitted by the Partnership & VCS Officer. 2. Community Defibrillators - Single Supplier Request: 21 - 24 To consider the written report by the Partnerships & VCS Officer. Legal and Governance | Harrogate Borough Council | PO Box 787 | Harrogate | HG1 9RW 01423 500600 www.harrogate.gov.uk This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 1 Agenda Item No. REPORT TO: Leader Meeting DATE: 24 October 2018 SERVICE AREA: Legal and Governance REPORTING OFFICER: Partnership & VCS Officer Fiona Friday SUBJECT: Community Defibrillator Scheme Endorsement 2018 WARD/S AFFECTED: ALL DISTRICT FORWARD PLAN REF: N/A 1.0 PURPOSE OF REPORT To seek approval from the Leader of the Council for awards of defibrillators to 17 projects as recommended by the defibrillator grants panel. 2.0 RECOMMENDATION/S 2.1 That the Leader of the Council approve awards of community defibrillators to the 17 recommended projects. (Appendix 1). 3.0 RECOMMENDED REASON/S FOR DECISION/S 3.1 The community defibrillator scheme is a partnership project funded equally between Harrogate Lions Club and the council (£10,000 contribution by each partner). By approving the awards additional community defibrillators will be installed across the Harrogate district. The successful applicants will be provided with a defibrillator approved by Yorkshire Ambulance Service and the council to enable the defibrillator to be mounted on an external wall for maximum public access. -

RGP LTE Beta

RPG LTE: Swords and Sorcery - Beta Edition Animals, Vehicles, and Hirelings Armor: - Armor Rating 7 Small 80 Medium 170 There may come a time when the party of adventurers has more to carry or defend Large 300 than they can on their own or are traveling in land foreign to them. In these cases Heavy – Armor Rating +2 +30 the purchasing of animals and vehicles, and the hiring of aid may be necessary. The Saddlebag 5 following charts should serve as a general guide for such scenarios. Bridle and Reigns 15-25 For animals the price refers to the average cost the animal would be at a trader, Muzzle 7-14 while the upkeep refers to the average price of daily supplies the animal needs to be Harness 20-30 kept alive and in good health (the average cost of stabling for a night). Blinders 6-13 Horses Whip 6 Type Price Upkeep Cage 10-100 Packhorse (Pony) 50 1 Sled 20 Riding Horse (Rouncey*, Hackney**) 75 1 Smooth Hunting/Riding Horse (Palfrey) 250 2 Carts – 2-wheeled vehicles Swift Warhorse (Courser) 100 2 Item Cost Strong Warhorse (Destrier) 300 3 Small (Push) Handcart 25 Draft Horse (Percheron) 75 1 Large (Pull) Handcart 40 * General purpose ** Riding specific Animal (Draw) Cart 50 Riding Cart – 2 Person 50 Pony – A small horse suitable for riding by Dwarves, Paulpiens, and other smaller Chariot 130 folk, or carrying a little less than a human riders weight in items. Rouncey – A medium-sized general purpose horse that can be trained as a warhorse, Wagons – 4-wheeled vehicles, 2-4 animals to pull. -

Nidderdale AONB State of Nature 2020

Nidderdale AONB State of Nature 2020 nidderdaleaonb.org.uk/stateofnature 1 FORWARD CONTENTS Forward by Lindsey Chapman Contents I’m proud, as Patron of The Wild Only by getting people involved 4 Headlines Watch, to introduce this State of in creating these studies in large Nature report. numbers do we get a proper 5 Our commitments understanding of what’s happening Growing up, I spent a lot of time in our natural world now. Thanks 6 Summary climbing trees, wading in streams to the hundreds of people and crawling through hedgerows. who took part, we now know 8 Background to the Nidderdale AONB I loved the freedom, adventure more than ever before about State of Nature report and wonder that the natural the current state of Nidderdale world offered and those early AONB’s habitats and wildlife. 14 Overview of Nidderdale AONB experiences absolutely shaped While there is distressing news, who I am today. such as the catastrophic decline 17 Why is nature changing? of water voles, there is also hope As a TV presenter on shows like for the future when so many Lindsey Chapman 30 Local Action and people TV and Radio Presenter the BBC’s Springwatch Unsprung, people come together to support The Wild Watch Patron Habitat coverage Big Blue UK and Channel 5’s their local wildlife. 43 Springtime on the Farm, I’m 46 Designated sites passionate about connecting This State of Nature report is just people with nature. The more a start, the first step. The findings 53 Moorland we understand about the natural outlined within it will serve world, the more we create as a baseline to assess future 65 Grassland and farmland memories and connections, the habitat conservation work. -

Washburn Heritage Centre Archive Handlist

WASHBURN HERITAGE CENTRE ARCHIVE HANDLIST The WHC Archive is a specialist collection of photographs, film, video and sound recordings, documents, memorabilia and ephemera relevant to the History, Heritage and Environment of the Washburn Valley. Our work to catalogue the collections is ongoing and this handlist will change as more of our current collections are catalogued. Please email us if you have a specific enquiry not covered by this handlist. The General Collections include: DOC Documents held by the centre either virtually and/or physically EX Past Exhibition panels PRI printed materials held in the centre RES Research materials including documents and notes on: RESVAR-Vernacular Architecture RESSOC-Social History RESNAT-The Natural World RESIND- Industry RESCHU- Churches and Chapels RESARCH-Archaeology RESWAT-Waterways and Bridges MAP Digital images of maps of the area including ordnance survey maps. PHO Photographs on various themes of interest to the local area including: PHOCHUR-churches and chapels PHOHIST- general history PHONAT-the natural World PHOHIST-general history () PHOWAR-War PHOLIP-Landscape, Industry and Places () PHOWHC-General events at Washburn Heritage centre, including the building and opening of the Centre VID - series of OHP films including: War memories, Water and leisure, Working wood, working Washburn, Haymaking-Washburn Show, Schools, Memories Day-launch of the OHP WHC-Opening Ceremony. · The special collections include: ARCH and - PHOFEW Fewston Assemblage-the archaeology reports and images of the finds PHOALH Alex Houseman Collection- images of the Washburn valley donated by Alex Houseman Ruth Brown Collection - includes images of the local area and a scrapbook of PHOBRO information on the Tuly and Peel families. -

Horse Power: Social Evolution in Medieval Europe

ABSTRACT HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE My research is on the development of the horse as a status symbol in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Horses throughout history are often restricted to the upper classes in non-nomadic societies simply due to the expense and time required of ownership of a 1,000lb prey animal. However, between 1000 and 1300 the perceived social value of the horse far surpasses the expense involved. After this point, ownership of quality animals begins to be regulated by law, such that a well off merchant or a lower level noble would not be legally allowed to own the most prestigious mounts, despite being able to easily afford one. Depictions of horses in literature become increasingly more elaborate and more reflective of their owners’ status and heroic value during this time. Changes over time in the frequency of horses being used, named, and given as gifts in literature from the same traditions, such as from the Waltharius to the Niebelungenlied, and the evolving Arthurian cycles, show a steady increase in the horse’s use as social currency. Later epics, such as La Chanson de Roland and La Cantar del Mio Cid, illustrate how firmly entrenched the horse became in not only the trappings of aristocracy, but also in marking an individuals nuanced position in society. Katrin Boniface May 2015 HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE by Katrin Boniface A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

2019 UCI Road World Championships

2019 ROAD WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS YORKSHIRE GREAT BRITAIN yorkshire2019.co.uk 21 - 29 SEPTEMBER 2019 @yorkshire2019 #yorkshire2019 CONTENTS Media information . 3 Forewords . 4 Competition and media events schedule . 5 Introducing the UCI . 6 Introducing Yorkshire 2019 . 8 The Yorkshire 2019 Para-Cycling International . 10 Introducing the UCI Road World Championships . 12 Introducing the Rainbow Jersey . 16 A nation of cyclists . 17 Yorkshire: The Rainbow County . 18 UCI Bike Region Label . 19 History makers . 20 Host towns . 22 Harrogate maps . 24 Other host locations . 26 Main Media Centre . 28 Media parking and broadcast media . 30 Photographers . 31 Mixed Zone . 32 Race routes . 34 Race programme . 35 02 DAY 1 Yorkshire 2019 Para-Cycling International . 36 DAY 2 Team Time Trial Mixed Relay . 38 DAY 3 Women Junior Individual Time Trial Men Junior Individual Time Trial . 42 DAY 4 Men Under 23 Individual Time Trial Women Elite Individual Time Trial . 46 DAY 5 Men Elite Individual Time Trial . 48 DAY 6 Men Junior Road Race . 50 DAY 7 Women Junior Road Race . 52 Men Under 23 Road Race . 54 DAY 8 Women Elite Road Race . 56 DAY 9 Men Elite Road Race . 58 Follow the Championships . 60 UCI Commissaires’ Panel . 62 Useful information . 63 MEDIA INFORMATION Union Cycliste Yorkshire 2019 Internationale (Local Organising Committee) Louis Chenaille Charlie Dewhirst UCI Press Officer Head of Communications louis .chenaille@uci .ch Charlie .Dewhirst@Yorkshire2019 .co .uk +41 79 198 7047 Mobile: +44 (0)7775 707 703 Xiuling She Nick Howes EBU Host Broadcaster -

£525,000 West House Farm, Wilsill, Hg3

WEST HOUSE FARM, WILSILL, HG3 5EA £525,000 WEST HOUSE FARM, WILSILL, NEAR PATELEY BRIDGE, HG3 5EA A most attractive detached Dales farmhouse revealing spacious and beautifully presented accommodation with ample parking, occupying an elevated position with large private landscaped gardens and delightful distant views. This wonderful home reveals a wealth of charm and character with magnificent features dating back to the 17th century, complemented by large private gardens thoughtfully landscaped with far-reaching views. The well-proportioned living space, which benefits from double glazing and gas central heating throughout, comprises large living room with feature fireplace and mullioned window, dining room, spacious farmhouse breakfast kitchen, snug, conservatory with far-reaching views. The turned spindle staircase leads to a galleried landing, large master bedroom, two further double bedrooms and luxury bathroom. West House Farm is delightfully situated in the heart of Nidderdale approximately one mile from the Dales town of Pateley Bridge. The fashionable spa town of Harrogate is approximately only 12 miles distant. 3 Reception Rooms Conservatory Kitchen Utility / Cloakroom 3 Bedrooms House Bathroom Extensive Gardens ACCOMMODATION GROUND FLOOR KITCHEN FIRST FLOOR ENTRANCE PORCH Fitted with an extensive range LANDING With front door leads to - of modem wall and base units with working surfaces having BEDROOM 1 LOUNGE inset ceramic single drainer sink Large master bedroom with double With two double glazed window to unit plus wicker storage baskets, glazed windows to front have far front and side. Two central heating shelving and glazed display reaching views. Central heating radiators. Feature stone fireplace cabinets. Double glazed window. radiator. with multi-fuel burning stove.