Packhorse Grazing Behavior and Immediate Impact on a Timberline Meadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Anderson, Known on the Trail As Mendorider, Is

More than 46,000 miles on horseback... and counting By Susan Bates d Anderson, known on the trail as MendoRider, is – and suffering – but, of course, unwilling to admit it. By the end of one of the few elite horsemen who have safely com- the ride, the hair on the inside of his legs had been painfully pulled pleted the PCT on horseback. On his return from every and rolled into little black balls. His skin was rubbed raw. He decided outing, his horses were healthy and well-fed and had that other than his own two legs and feet, the only transportation for been untroubled by either colic or injuries. him had to have either wheels or a sail. Jereen E Ed’s backcountry experience began in 1952 while he was still in Ed and his wife, , once made ambitious plans to sail high school, and by 1957 he had hiked the John Muir Trail section around the world. But the reality of financial issues halted their aspi- of the PCT. He continued to build on that experience by hiking rations to purchase a suitable boat. They choose a more affordable and climbing in much of the wilderness surrounding the PCT in option: they would travel and live in a Volkswagen camper. California. He usually went alone. Ed didn’t like any of the VW conversions then available on either Ed was, and is, most “at home” and comfortable in the wilderness side of the Atlantic, so, he designed and built his own. He envisioned – more so than at any other time or in any other place. -

The Sami and the Inupiat Finding Common Grounds in a New World

The Sami and the Inupiat Finding common grounds in a new world SVF3903 Kristine Nyborg Master of Philosophy in Visual Cultural Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Department of Archaeology and Social Anthropology University of Tromsø Spring 2010 2 Thank you To all my informants for helping me make this project happen and for taking me into your lives and sharing all your wonderful thoughts. I am extremely grateful you went on this journey with me. A special warm thanks to my main informant who took me in and guided the way. This would have been impossible without you, and your great spirits and laughter filled my thoughts as I was getting through this process. To supervisor, Bjørn Arntsen, for keeping me on track and being so supportive. And making a mean cup of latte. To National Park Service for helping me with housing. A special thanks to the Center for Sami Studies Strategy Fund for financial support. 3 Abstract This thesis is about the meeting of two indigenous cultures, the Sami and the Inupiat, on the Alaskan tundra more than a hundred years ago. The Sami were brought over by the U.S. government to train the Inupiat in reindeer herding. It is about their adjustment to each other and to the rapidly modernizing world they found themselves a part of, until the term indigenous became a part of everyday speech forty years ago. During this process they gained new identities while holding on to their indigenous ones, keeping a close tie to nature along the way. -

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-Playing Games

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-playing Games Throughout the Middle Ages the horse was a powerful symbol of social differences but also a tool for the farmer, merchant and fighting classes. While the species varied considerably, as did their names, here is a summary of the main types encountered across Medieval Europe. Great Horse - largest (15-16 hands) and heaviest (1.5-2t) of horses, these giants were the only ones capable of bearing a knight in full plate armour. However such horses lacked speed and endurance. Thus they were usually reserved for tourneys and jousts. Modern equivalent would be a «shire horse». Mules - commonly used as a beast of burden (to carry heavy loads or pull wagons) but also occasionally as a mount. As mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses, they were particularly useful for strenuous support tasks, such as hauling supplies over difficult terrain. Hobby – a tall (13-14 hands) but lightweight horse which is quick and agile. Developed in Ireland from Spanish or Libyan (Barb) bloodstock. This type of quick and agile horse was popular for skirmishing, and was often ridden by light cavalry. Apparently capable of covering 60-70 miles a single day. Sumpter or packhorse - a small but heavier horse with excellent endurance. Used to carry baggage, this horse could be ridden albeit uncomfortably. The modern equivalent would be a “cob” (2-3 mark?). Rouncy - a smaller and well-rounded horse that was both good for riding and carrying baggage. Its widespread availability ensured it remained relatively affordable (10-20 marks?) compared to other types of steed. -

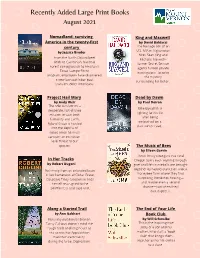

July Recently Added Large Print

Recently Added Large Print Books August 2021 Nomadland: surviving King and Maxwell America in the twenty-first by David Baldacci The teenage son of an century U.S. MIA in Afghanistan by Jessica Bruder hires Sean King and From the North Dakota beet Michelle Maxwell-- fields to California's National former Secret Service Forest campgrounds to Amazon's agents turned private Texas CamperForce investigators--to solve program, employers have discovered the mystery a new low-cost labor pool: surrounding his father. transient older Americans. Project Hail Mary Dead by Dawn by Andy Weir by Paul Doiron The sole survivor on a Mike Bowditch is desperate, last-chance fighting for his life mission to save both after being humanity and Earth, ambushed on a Ryland Grace is hurtled dark winter road, into the depths of space when he must conquer an extinction- level threat to our species. The Music of Bees by Eileen Garvin Three lonely strangers in a rural In Her Tracks Oregon town, each working through by Robert Dugoni grief and life's curveballs are brought Returning from an extended leave together by happenstance on a local in her hometown of Cedar Grove, honeybee farm where they find Detective Tracy Crosswhite finds surprising friendship, healing— herself reassigned to the and maybe even a second Seattle PD's cold case unit. chance—just when they l east expect it. Along a Storied Trail The End of Your Life by Ann Gabhart Book Club Kentucky packhorse librarian by Will Schwalbe Tansy Calhoun doesn't mind the This is the inspiring true rough trails and long hours as story of a son and his she serves her Appalachian mother, who start a "book mountain community club" that brings them during the Great Depression. -

RGP LTE Beta

RPG LTE: Swords and Sorcery - Beta Edition Animals, Vehicles, and Hirelings Armor: - Armor Rating 7 Small 80 Medium 170 There may come a time when the party of adventurers has more to carry or defend Large 300 than they can on their own or are traveling in land foreign to them. In these cases Heavy – Armor Rating +2 +30 the purchasing of animals and vehicles, and the hiring of aid may be necessary. The Saddlebag 5 following charts should serve as a general guide for such scenarios. Bridle and Reigns 15-25 For animals the price refers to the average cost the animal would be at a trader, Muzzle 7-14 while the upkeep refers to the average price of daily supplies the animal needs to be Harness 20-30 kept alive and in good health (the average cost of stabling for a night). Blinders 6-13 Horses Whip 6 Type Price Upkeep Cage 10-100 Packhorse (Pony) 50 1 Sled 20 Riding Horse (Rouncey*, Hackney**) 75 1 Smooth Hunting/Riding Horse (Palfrey) 250 2 Carts – 2-wheeled vehicles Swift Warhorse (Courser) 100 2 Item Cost Strong Warhorse (Destrier) 300 3 Small (Push) Handcart 25 Draft Horse (Percheron) 75 1 Large (Pull) Handcart 40 * General purpose ** Riding specific Animal (Draw) Cart 50 Riding Cart – 2 Person 50 Pony – A small horse suitable for riding by Dwarves, Paulpiens, and other smaller Chariot 130 folk, or carrying a little less than a human riders weight in items. Rouncey – A medium-sized general purpose horse that can be trained as a warhorse, Wagons – 4-wheeled vehicles, 2-4 animals to pull. -

Horse Power: Social Evolution in Medieval Europe

ABSTRACT HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE My research is on the development of the horse as a status symbol in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Horses throughout history are often restricted to the upper classes in non-nomadic societies simply due to the expense and time required of ownership of a 1,000lb prey animal. However, between 1000 and 1300 the perceived social value of the horse far surpasses the expense involved. After this point, ownership of quality animals begins to be regulated by law, such that a well off merchant or a lower level noble would not be legally allowed to own the most prestigious mounts, despite being able to easily afford one. Depictions of horses in literature become increasingly more elaborate and more reflective of their owners’ status and heroic value during this time. Changes over time in the frequency of horses being used, named, and given as gifts in literature from the same traditions, such as from the Waltharius to the Niebelungenlied, and the evolving Arthurian cycles, show a steady increase in the horse’s use as social currency. Later epics, such as La Chanson de Roland and La Cantar del Mio Cid, illustrate how firmly entrenched the horse became in not only the trappings of aristocracy, but also in marking an individuals nuanced position in society. Katrin Boniface May 2015 HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE by Katrin Boniface A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

A World of Books in This First Module, a World of Books, We Will Study the Power of Books and Libraries Around the World

MODULE 1 What’s Happening in English Language Arts Class? Your child’s class will use Wit & Wisdom as our English Language Arts curriculum. FIRST GRADE By reading and responding to excellent fiction and nonfiction, your student will learn about key history, science, and literature topics. A World of Books In this first module, A World of Books, we will study the power of books and libraries around the world. Some people have climbed mountains just to find books. Others have used boats or even on elephants to get to libraries. In this module, we will ask: How do books—and the knowledge they bring—change lives around the world? OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS: LOOK AT THIS PAINTING: Nonfiction Picture Books • Museum ABC by The Metropolitan • The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Grant Museum of Art Wood • My Librarian Is a Camel by Margriet Ruurs Fiction Picture Books • Tomás and the Library Lady by Pat Mora and Raul Colon • Waiting for the Biblioburro by Monica Brown and John Parra • That Book Woman by Heather Henson and David Small • Green Eggs and Ham by Dr. Seuss Find all the links online at http://bit.ly/witwisdom1st © Great Minds PBC www.baltimorecityschools.org/elementary-school OUR CLASS WILL ASK THESE VOCABULARY QUESTIONS: For their tests, your child should know the • How do library books change life for meaning of each word. They should also Tomás? know how to use each word in a sentence: • How does the Biblioburro change life for Ana? • Borrow • Scholar • How do people around the world get • Eager • Portrait books? • Imagination • Duck • How does the packhorse librarian change • Migrant • Landscape life for Cal? • Inspire • Signs • How do books change my life? • Remote • Still life • Mobile OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS: • “Biblioburro: The Donkey Library,” Ebonne Ruffins, CNN • “Pack Horse Librarians,” SLIS Storytelling Snapshot: In this first module, A World of Books, your child PRACTICING AT HOME will learn about the power WRITING, TALKING AND READING of books and libraries around the world. -

The Worth Way LANE

KEIGHLEY CAVENDISH ST Keighley Station LOW MILL The Worth Way LANE 11 mile/17.5km circular walk or a EAST PARADE 1 Low 5 /2 mile/8.75km linear walk (returning to Keighley either by bus Bridge Mill or train from Oxenhope). PARKWOOD STREET WORTH WAY PARK (Allow at least 6 hours to complete the 11 mile/17.5km walk). LANE Parkwood The Walk Greengate Knowle Mill WOODHOUSE ROAD SOUTH STREET Woodhouse Museum Crag Place Crag Hill Ingrow Station Farm Ingrow Kirkstall Wood y a w il a R y e ll a short unofficial V h diversion t HAINWORTH r LANE o River Worth W d n The Keighley and Worth Valley Railway Line Bracken Bank a y e l h Hainworth g i e K D E DAMEMS ROAD AM MS Damems LA NE Station SYKE LN. GOOSE COTE LANE Damems Hill Top Harewood level Hill crossing E Cackleshaw G D New House E Farm R EAST O ROYD O STATION M ROAD S Oakworth Oakworth HALIFAX ROAD (A629) Station E level E PROVIDENCE crossing L LANE VALE MILL LANE Hebble Row reservoir Toll tunnel House VICTORIA AVE. Barcroft ROAD EY EB L River Worth O NG R L I Mytholmes A HAWORTH ROAD B N E LEES LANE Cross Roads HALIFAX ROAD (A629) MYTHOLMES LANE Haworth Sugden H school A Station Reservoir R playing D G fields A MILL HEY T E L A N Haworth E BROW TOP ROAD CENTRAL PARK STATION ROAD STATION Stump Cross BROW Farm BRIDGHOUSE ROAD LANE Naylor Hill Quarry, Brow Moor BROW MOOR War Memorial Bridgehouse Beck HEBDEN ROAD Wind Turbine CULLINGWORTH Naylor Hill MOOR Quarry diversion to viewpoint Lower NaylorHill Upper Naylor Farm Hill Farm y a Ives w l i Bottom a R y y e l l Donkey MARSH LANE a V Bridge BLACK MOOR ROAD h Delf Hill t r o W d n a y le h ig e North K Birks Sewage MOORHOUSE LANE Works Oxenhope Station Key KEIGHLEY ROAD Lower Route Hayley NE MILL LA HARRY Farm LANE DARK LANE OS Map Oxenhope Sue Explorer 21 Ryder N Manorlands South Pennines Donkey Bridge, Bridgehouse Valley City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Countryside & Rights of Way Starting at Keighley Railway Station with your back to the The Worth Way building, turn left at the station forecourt and immediately left again down the cobbled Low Mill Lane. -

First Episode

May 18, Monday. Rode to Sun River Land & Livestock Co. ranch. Then to Witmer ranch, 9 to 2:30 p.~. Delivered Willow Creek Stock Co.'s permit to Foreman Brooks. ~ay 19, Tuesday. Counted for Willow Creek Stock Co. 235 head cattle; for E. S. Anderson 60 head; and 12 head for G. W. Hamilton on Division 6. Found 60 head cattle and 25 horses, property of Joe Ford branded ~ on left side, horses on left hip. With the assistance of E. S. Anderson, Wm. Crispin, Jos. Owens, Robert Brooks, J. T. Weimer drove same into Ford's pasture and partially repaired fence. Requested Mr. Henry Ford, in presence of above-named parties. to notify Mr. Joe Ford to repair fence and keep cattle off the Forest. 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. May 20. Wednesday. Rained and snowed all day. May 21, Thursday. Counted 128 head cattle for E. J. and Mrs. Murphy; 72 head for E. S. Anderson. and 37 head for John Willard. Rode to E. Beach ranch, camped. 7 to 4:30. May 22, Friday. Rained until 2 p.m. Counted 500 head of cattle into Division 4 for E. Beach. 10 to 7 p.m. May 23. Saturday. Left Beach ranch 6 a.m., arrived Hannan Gulch l! a.m. Left Hannan 3:20 p.m. James Caldwell ranch 7:30 p.m. Stopped Palmer's for supper. May 24, Sunday. Counted 300 head of cattle for McDonald and Rimel!. 147 head for Woolman & Christian. Hannan Gulch 3 p.m. 7 to 3. May 25, Monday. -

Timeline of the Development of the Horse

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 177 August, 2007 Timeline of the Development of the Horse by Beverley Davis Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. Sinographs (hanzi, also called tetragraphs [fangkuaizi]) and other unusual symbols should be kept to an absolute minimum. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Reference Manual TABLE of CONTENTS

Rev. 12/8/17 Montana Department of Labor and Industry Montana Board of Outfitters OUTFITTER EXAMINATION PACKING SERVICES LICENSE ENDORSEMENT RESOURCE MANUAL Montana Board of Outfitters Packing Services Reference Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. EQUINE OPERATIONS a. Client Communication b. Rider Assessment and Evaluation c. Rider Management d. Staff Management e. Livestock Management f. Facilities Management g. Incident Management II. ANIMAL CARE AND TRAINING a. Livestock Care & Preventative Maintenance b. Packing Livestock c. Leading Livestock d. Proper Training for Livestock e. Transporting Livestock in Trailers III. EQUIPMENT a. Basic Requirements of Riding and Pack Equipment b. Proper Fitting to Animal c. Proper Care of Equipment d. Personal Protective Equipment IV. STANDARDS AND PROCEDURES FOR CONDUCTING TRIPS a. Planning a Pack Trip b. Trip Expectations c. Knowledge of the Area d. Time of Year/Expected Weather e. Type of Equipment f. Meal Planning and Preparation V. LAND USE AND PUBLIC INTERFACE a. Agency Regulations b. Getting Along in the Backcountry - Backcountry Manners c. Grazing Management d. Good Camping Rules e. Fire Safety f. Wilderness Act VI. LLAMAS AND OTHER ANIMALS a. Other Types of Pack Stock b. Safety and Interaction Considerations Montana Board of Outfitters Packing Services Reference Manual INTRODUCTION For years the Montana Board of Outfitters utilized a book authored by one of the most experienced and heralded backcountry Outfitters, Smoke Elser, for the basis of testing Outfitters seeking a packing endorsement as an addition to their Outfitter’s license. The book, “PACKING IN ON MULES AND HORSES,” is still considered one of the best “How To” guidebooks in the industry. -

1 Life at Packhorse Farm Owen Mackie My Brother Richard and I

1 Life at Packhorse Farm Owen Mackie My brother Richard and I were evacuated to Canada in 1940 but our parents stayed on in Bristol at 3 Goldney Ave, and my father went on working as Chief Medical Officer of Imperial Airways (now BA). They were still there with our dog Timmy, and the war was still on, when I got back to England in spring 1944. Richard stayed on in Canada to finish his Bachelor’s degree at the University of Toronto. Our half-brother Lawrence had served through the war in the Royal Navy and was now completing his medical training at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford. Bristol had been heavily bombed early in the war and my parents were involved in civil defence as air raid wardens, and Daddy in his capacity as a doctor. This picture shows them in their ARP (Air Raid Precautions) uniforms. The worst of the bombing was over in 1941 but occasional raids took place on Bristol as late at May 1944 while we were still there. We later learned that the Germans had built V2 rocket launching sites in northern France with Bristol as their intended target. Fortunately for us, these were overrun by the Allied invasion of Normandy in the summer of 1944 and the awesome V2s – thirteen-ton ballistic missiles 2 flying at supersonic speeds - never got off their launching pads. (von Braun, head of the German V2 design team, was snapped up by the US Army and subsequently became director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and the chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle which took the Apollo 11 landing craft to the moon in 1969).