The Sami and the Inupiat Finding Common Grounds in a New World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ed Anderson, Known on the Trail As Mendorider, Is

More than 46,000 miles on horseback... and counting By Susan Bates d Anderson, known on the trail as MendoRider, is – and suffering – but, of course, unwilling to admit it. By the end of one of the few elite horsemen who have safely com- the ride, the hair on the inside of his legs had been painfully pulled pleted the PCT on horseback. On his return from every and rolled into little black balls. His skin was rubbed raw. He decided outing, his horses were healthy and well-fed and had that other than his own two legs and feet, the only transportation for been untroubled by either colic or injuries. him had to have either wheels or a sail. Jereen E Ed’s backcountry experience began in 1952 while he was still in Ed and his wife, , once made ambitious plans to sail high school, and by 1957 he had hiked the John Muir Trail section around the world. But the reality of financial issues halted their aspi- of the PCT. He continued to build on that experience by hiking rations to purchase a suitable boat. They choose a more affordable and climbing in much of the wilderness surrounding the PCT in option: they would travel and live in a Volkswagen camper. California. He usually went alone. Ed didn’t like any of the VW conversions then available on either Ed was, and is, most “at home” and comfortable in the wilderness side of the Atlantic, so, he designed and built his own. He envisioned – more so than at any other time or in any other place. -

Eskimos, Reindeer, and Land

ESKIMOS, REINDEER, AND LAND Richard O. Stern Edward L. Arobio Larry L. Naylor and Wayne C. Thomas* Bulletin 59 December 1980 *Richard O. Stern is formerly a research associate in anthropology at the Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska. Fairbanks. He is currently historian for the Alaska Department of Nat•ural Resources, Division of Forest, Land, and Water Management. Edward L. Arobio is a research associate in economics at the Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Larry L. Naylor is formerly an assistant professor of anthropology at the Department of Anthropology. University of Alaska. Fairbanks. He is currently anthropology director at North Texas State University, Denron. Wayne C. Thomas is an associate professor of economics at the Agricultural Experiment Station. University of Alaska, Fairbanks. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures Table of Photos Table of Tables Preface Chapter I–Introduction Chapter II – Reindeer Biology and Ecology Reindeer Biology and Life Cycle Forage Requirements and Carrying Capacity Antler Growth and Function Reindeer Ecology Generalized Yearly Herding Activity Chapter III – Introduction of Reindeer Herding in Alaska General Historical Summary Conditions Prior to the Introduction of Reindeer Reindeer Introduction Early Development Chapter IV – Non–Native Ownership of Reindeer: 1914–1940 Lomen and Company Epidemics, Company Herds, and Fairs Reindeer Investigations Reindeer Act of 1937 Chapter V – Native Ownership and the Period of Reconstruction: 1940–1977 The1940s The1950s -

John Michael Lang Fine Books

John Michael Lang Fine Books [email protected] (206) 624 4100 5416 – 20th Avenue NW Seattle, WA 98107 USA 1. [American Politics] Memorial Service Held in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, Together With Tributes Presented in Euology of Henry M. Jackson, Late a Senator From Washington. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983. 9" x 5.75". 457pp. Black cloth with gilt lettering. Fine condition. This copy signed and inscribed by Jackson's widow to a prominent Seattle journalist and advertising man: "Dear Jerry [Hoeck], I thought you would want to have a copy of this memorial volume. It comes with my deepest appreciation for your many years of friendship with our family and gratitude for your moving tribute to Scoop in the "Seattle Weekly" (p. 255.) sincerely Helen." (The page number refers to the page where Hoeck's tribute is reprinted in this volume.) Per Hoeck's obituary: "Hoeck's advertising firm] handled all of Scoop's successful Senatorial campaigns and campaigns for Senator Warren G. Magnuson. During the 1960 presidential campaign Jerry packed his bags and worked tirelessly as the advertising manager of the Democratic National Committee and was in Los Angeles to celebrate the Kennedy win. Jerry also was up to his ears in Scoop's two unsuccessful attempts to run for President in '72 and '76 but his last effort for Jackson was his 1982 senatorial re-election campaign, a gratifying landslide." $75.00 2. [California] Edwards, E. I. Desert Voices: A Descriptive Bibliography. Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1958. -

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-Playing Games

Horse Breeds in Medieval Role-playing Games Throughout the Middle Ages the horse was a powerful symbol of social differences but also a tool for the farmer, merchant and fighting classes. While the species varied considerably, as did their names, here is a summary of the main types encountered across Medieval Europe. Great Horse - largest (15-16 hands) and heaviest (1.5-2t) of horses, these giants were the only ones capable of bearing a knight in full plate armour. However such horses lacked speed and endurance. Thus they were usually reserved for tourneys and jousts. Modern equivalent would be a «shire horse». Mules - commonly used as a beast of burden (to carry heavy loads or pull wagons) but also occasionally as a mount. As mules are often both calmer and hardier than horses, they were particularly useful for strenuous support tasks, such as hauling supplies over difficult terrain. Hobby – a tall (13-14 hands) but lightweight horse which is quick and agile. Developed in Ireland from Spanish or Libyan (Barb) bloodstock. This type of quick and agile horse was popular for skirmishing, and was often ridden by light cavalry. Apparently capable of covering 60-70 miles a single day. Sumpter or packhorse - a small but heavier horse with excellent endurance. Used to carry baggage, this horse could be ridden albeit uncomfortably. The modern equivalent would be a “cob” (2-3 mark?). Rouncy - a smaller and well-rounded horse that was both good for riding and carrying baggage. Its widespread availability ensured it remained relatively affordable (10-20 marks?) compared to other types of steed. -

July Recently Added Large Print

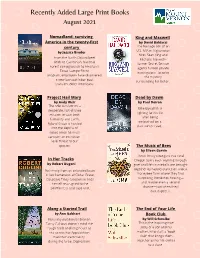

Recently Added Large Print Books August 2021 Nomadland: surviving King and Maxwell America in the twenty-first by David Baldacci The teenage son of an century U.S. MIA in Afghanistan by Jessica Bruder hires Sean King and From the North Dakota beet Michelle Maxwell-- fields to California's National former Secret Service Forest campgrounds to Amazon's agents turned private Texas CamperForce investigators--to solve program, employers have discovered the mystery a new low-cost labor pool: surrounding his father. transient older Americans. Project Hail Mary Dead by Dawn by Andy Weir by Paul Doiron The sole survivor on a Mike Bowditch is desperate, last-chance fighting for his life mission to save both after being humanity and Earth, ambushed on a Ryland Grace is hurtled dark winter road, into the depths of space when he must conquer an extinction- level threat to our species. The Music of Bees by Eileen Garvin Three lonely strangers in a rural In Her Tracks Oregon town, each working through by Robert Dugoni grief and life's curveballs are brought Returning from an extended leave together by happenstance on a local in her hometown of Cedar Grove, honeybee farm where they find Detective Tracy Crosswhite finds surprising friendship, healing— herself reassigned to the and maybe even a second Seattle PD's cold case unit. chance—just when they l east expect it. Along a Storied Trail The End of Your Life by Ann Gabhart Book Club Kentucky packhorse librarian by Will Schwalbe Tansy Calhoun doesn't mind the This is the inspiring true rough trails and long hours as story of a son and his she serves her Appalachian mother, who start a "book mountain community club" that brings them during the Great Depression. -

RGP LTE Beta

RPG LTE: Swords and Sorcery - Beta Edition Animals, Vehicles, and Hirelings Armor: - Armor Rating 7 Small 80 Medium 170 There may come a time when the party of adventurers has more to carry or defend Large 300 than they can on their own or are traveling in land foreign to them. In these cases Heavy – Armor Rating +2 +30 the purchasing of animals and vehicles, and the hiring of aid may be necessary. The Saddlebag 5 following charts should serve as a general guide for such scenarios. Bridle and Reigns 15-25 For animals the price refers to the average cost the animal would be at a trader, Muzzle 7-14 while the upkeep refers to the average price of daily supplies the animal needs to be Harness 20-30 kept alive and in good health (the average cost of stabling for a night). Blinders 6-13 Horses Whip 6 Type Price Upkeep Cage 10-100 Packhorse (Pony) 50 1 Sled 20 Riding Horse (Rouncey*, Hackney**) 75 1 Smooth Hunting/Riding Horse (Palfrey) 250 2 Carts – 2-wheeled vehicles Swift Warhorse (Courser) 100 2 Item Cost Strong Warhorse (Destrier) 300 3 Small (Push) Handcart 25 Draft Horse (Percheron) 75 1 Large (Pull) Handcart 40 * General purpose ** Riding specific Animal (Draw) Cart 50 Riding Cart – 2 Person 50 Pony – A small horse suitable for riding by Dwarves, Paulpiens, and other smaller Chariot 130 folk, or carrying a little less than a human riders weight in items. Rouncey – A medium-sized general purpose horse that can be trained as a warhorse, Wagons – 4-wheeled vehicles, 2-4 animals to pull. -

Horse Power: Social Evolution in Medieval Europe

ABSTRACT HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE My research is on the development of the horse as a status symbol in Western Europe during the Middle Ages. Horses throughout history are often restricted to the upper classes in non-nomadic societies simply due to the expense and time required of ownership of a 1,000lb prey animal. However, between 1000 and 1300 the perceived social value of the horse far surpasses the expense involved. After this point, ownership of quality animals begins to be regulated by law, such that a well off merchant or a lower level noble would not be legally allowed to own the most prestigious mounts, despite being able to easily afford one. Depictions of horses in literature become increasingly more elaborate and more reflective of their owners’ status and heroic value during this time. Changes over time in the frequency of horses being used, named, and given as gifts in literature from the same traditions, such as from the Waltharius to the Niebelungenlied, and the evolving Arthurian cycles, show a steady increase in the horse’s use as social currency. Later epics, such as La Chanson de Roland and La Cantar del Mio Cid, illustrate how firmly entrenched the horse became in not only the trappings of aristocracy, but also in marking an individuals nuanced position in society. Katrin Boniface May 2015 HORSE POWER: SOCIAL EVOLUTION IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE by Katrin Boniface A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

A World of Books in This First Module, a World of Books, We Will Study the Power of Books and Libraries Around the World

MODULE 1 What’s Happening in English Language Arts Class? Your child’s class will use Wit & Wisdom as our English Language Arts curriculum. FIRST GRADE By reading and responding to excellent fiction and nonfiction, your student will learn about key history, science, and literature topics. A World of Books In this first module, A World of Books, we will study the power of books and libraries around the world. Some people have climbed mountains just to find books. Others have used boats or even on elephants to get to libraries. In this module, we will ask: How do books—and the knowledge they bring—change lives around the world? OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS: LOOK AT THIS PAINTING: Nonfiction Picture Books • Museum ABC by The Metropolitan • The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Grant Museum of Art Wood • My Librarian Is a Camel by Margriet Ruurs Fiction Picture Books • Tomás and the Library Lady by Pat Mora and Raul Colon • Waiting for the Biblioburro by Monica Brown and John Parra • That Book Woman by Heather Henson and David Small • Green Eggs and Ham by Dr. Seuss Find all the links online at http://bit.ly/witwisdom1st © Great Minds PBC www.baltimorecityschools.org/elementary-school OUR CLASS WILL ASK THESE VOCABULARY QUESTIONS: For their tests, your child should know the • How do library books change life for meaning of each word. They should also Tomás? know how to use each word in a sentence: • How does the Biblioburro change life for Ana? • Borrow • Scholar • How do people around the world get • Eager • Portrait books? • Imagination • Duck • How does the packhorse librarian change • Migrant • Landscape life for Cal? • Inspire • Signs • How do books change my life? • Remote • Still life • Mobile OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS: • “Biblioburro: The Donkey Library,” Ebonne Ruffins, CNN • “Pack Horse Librarians,” SLIS Storytelling Snapshot: In this first module, A World of Books, your child PRACTICING AT HOME will learn about the power WRITING, TALKING AND READING of books and libraries around the world. -

Alaska Reindeer Herdsmen

ALASKA REINDEER HERDSMEN ALASKA REINDEER HERDSMEN A Study of Native Management in Transition by Dean Francis Olson Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research University of Alaska College, Alaska 99701 SEG Report No. 22 December 1969 Price: $5.00 Dean F. Olson, an associate of the Institute of Social, Economic and Government Research, is a member of the Faculty of Business, Uni versity of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He received his OBA from the University of Washington in 1968. iv PREFACE Reindeer husbandry is a peculiarly circumpolar endeavor. Of the three million domesticated reindeer estimated to exist in the northernmost nations of the world, just over 1 per cent are found in North America. The Soviet Union possesses about 80 per cent, and the Fennoscandian countries contain more than 18 per cent. There are about 30,000 in western Alaska, and the Canadian government estimates that some 2,700 range the Mackenzie River basin. Domesticated reindeer are not indigenous to North America. They were first introduced to this continent in 1892, when they were brought to western Alaska from various Siberian locations. The Canadian government purchased their parent stock from an Alaska producer in 1935. In each case, the objectives for importation were to broaden the resource base of the Native populations and to provide a means for social and economic de velopment in remote areas. The present study examines the role of Alaska reindeer as a Native resource. More specifically, it concerns the historical role of the Alaska Eskimo reindeer herdsmen, and examines their functions as managers of a re source and as instruments for social and economic change among their people. -

The Reindeer Botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901–1977

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2012 The Reindeer Botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901–1977 Dathan, Wendy University of Calgary Press Dathan, Patricia Wendy. "The reindeer botanist: Alf Erling Porsild, 1901-1977". Series: Northern Lights Series; 14, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49303 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE REINDEER BOTANIST: ALF ERLING PORSILD, 1901–1977 by Wendy Dathan ISBN 978-1-55238-587-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

The Worth Way LANE

KEIGHLEY CAVENDISH ST Keighley Station LOW MILL The Worth Way LANE 11 mile/17.5km circular walk or a EAST PARADE 1 Low 5 /2 mile/8.75km linear walk (returning to Keighley either by bus Bridge Mill or train from Oxenhope). PARKWOOD STREET WORTH WAY PARK (Allow at least 6 hours to complete the 11 mile/17.5km walk). LANE Parkwood The Walk Greengate Knowle Mill WOODHOUSE ROAD SOUTH STREET Woodhouse Museum Crag Place Crag Hill Ingrow Station Farm Ingrow Kirkstall Wood y a w il a R y e ll a short unofficial V h diversion t HAINWORTH r LANE o River Worth W d n The Keighley and Worth Valley Railway Line Bracken Bank a y e l h Hainworth g i e K D E DAMEMS ROAD AM MS Damems LA NE Station SYKE LN. GOOSE COTE LANE Damems Hill Top Harewood level Hill crossing E Cackleshaw G D New House E Farm R EAST O ROYD O STATION M ROAD S Oakworth Oakworth HALIFAX ROAD (A629) Station E level E PROVIDENCE crossing L LANE VALE MILL LANE Hebble Row reservoir Toll tunnel House VICTORIA AVE. Barcroft ROAD EY EB L River Worth O NG R L I Mytholmes A HAWORTH ROAD B N E LEES LANE Cross Roads HALIFAX ROAD (A629) MYTHOLMES LANE Haworth Sugden H school A Station Reservoir R playing D G fields A MILL HEY T E L A N Haworth E BROW TOP ROAD CENTRAL PARK STATION ROAD STATION Stump Cross BROW Farm BRIDGHOUSE ROAD LANE Naylor Hill Quarry, Brow Moor BROW MOOR War Memorial Bridgehouse Beck HEBDEN ROAD Wind Turbine CULLINGWORTH Naylor Hill MOOR Quarry diversion to viewpoint Lower NaylorHill Upper Naylor Farm Hill Farm y a Ives w l i Bottom a R y y e l l Donkey MARSH LANE a V Bridge BLACK MOOR ROAD h Delf Hill t r o W d n a y le h ig e North K Birks Sewage MOORHOUSE LANE Works Oxenhope Station Key KEIGHLEY ROAD Lower Route Hayley NE MILL LA HARRY Farm LANE DARK LANE OS Map Oxenhope Sue Explorer 21 Ryder N Manorlands South Pennines Donkey Bridge, Bridgehouse Valley City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council Countryside & Rights of Way Starting at Keighley Railway Station with your back to the The Worth Way building, turn left at the station forecourt and immediately left again down the cobbled Low Mill Lane. -

Between Empires and Frontiers Alaska Native Sovereignty and U.S. Settler Imperialism

Between Empires and Frontiers Alaska Native Sovereignty and U.S. Settler Imperialism A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jessica Arnett IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Jean M. O’Brien, Barbara Welke March, 2018 Copyright Jessica Arnett 2018 Acknowledgements My time in academia, first as an undergraduate, then an adjunct instructor, and finally as a graduate student, has spanned nearly two decades and involved numerous cross-country relocations. I cannot begin to assess the number of debts that I have accrued during this time, as friends, family members, devoted advisors, and colleagues supported the winding trajectory of my academic life. I am grateful for my committee and the years of insight and support they have provided for me as I developed my research questions and attempted to answer them. I am deeply indebted to my advisors, Jean O’Brien and Barbara Welke, who have tirelessly dedicated themselves to my project and have supported me through my many achievements and disappointments, both academic and personal. Jeani is an amazing historian who throughout my six years in Minnesota has continuously asked critical questions about my project that have triggered new ways of understanding what I was perceiving in the documentary record and how I eventually came to understand Alaska. Her immediate support and tireless enthusiasm for my radically different framing of Alaska’s relationship to the contiguous states and what that meant for Alaska Native sovereignty struggles encouraged me to continue theorizing settler imperialism and to have confidence that my research was not only worthwhile, but path breaking and relevant.