Cat Scratch Disease, Which Is Most Infections Often a Relatively Benign and Self-Limiting Illness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact of HIV on Gastroenterology/Hepatology

Core Curriculum: Impact of HIV on Gastroenterology/Hepatology AshutoshAshutosh Barve,Barve, M.D.,M.D., Ph.D.Ph.D. Gastroenterology/HepatologyGastroenterology/Hepatology FellowFellow UniversityUniversityUniversity ofofof LouisvilleLouisville Louisville Case 4848 yearyear oldold manman presentspresents withwith aa historyhistory ofof :: dysphagiadysphagia odynophagiaodynophagia weightweight lossloss EGDEGD waswas donedone toto evaluateevaluate thethe problemproblem University of Louisville Case – EGD Report ExtensivelyExtensively scarredscarred esophagealesophageal mucosamucosa withwith mucosalmucosal bridging.bridging. DistalDistal esophagealesophageal nodulesnodules withwithUniversity superficialsuperficial ulcerationulceration of Louisville Case – Esophageal Nodule Biopsy InflammatoryInflammatory lesionlesion withwith ulceratedulcerated mucosamucosa SpecialSpecial stainsstains forfor fungifungi revealreveal nonnon-- septateseptate branchingbranching hyphaehyphae consistentconsistent withwith MUCORMUCOR University of Louisville Case TheThe patientpatient waswas HIVHIV positivepositive !!!! University of Louisville HAART (Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy) HIV/AIDS Before HAART After HAART University of Louisville HIV/AIDS BeforeBefore HAARTHAART AfterAfter HAARTHAART ImmuneImmune dysfunctiondysfunction ImmuneImmune reconstitutionreconstitution OpportunisticOpportunistic InfectionsInfections ManagementManagement ofof chronicchronic ¾ Prevention diseasesdiseases e.g.e.g. HepatitisHepatitis CC ¾ Management CirrhosisCirrhosis NeoplasmsNeoplasms -

Recognizing and Treating New and Emerging Infections Encountered in Everyday Practice

Recognizing and treating new and emerging infections encountered in everyday practice STEVEN M. GORDON, MD NFECTIOUS DISEASES, pre- MiikWirj:« Although infectious diseases were once considered a dicted earlier in this cen- diminishing threat, new pathogens are constantly challenging tury to be eliminated as a the health care system. This article reviews the clinical presen- public health problem, re- tation, diagnosis, and treatment of seven emerging infections I main the chief cause of death that primary care physicians are likely to encounter. worldwide and a significant cause of death and morbidity in i Parvovirus B19 attacks erythrocyte precursors; the United States.1 Challenging infection is usually benign and self-limiting but can cause the US public health system are aplastic crises in patients with chronic hemolytic disorders. several newly identified patho- Hemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli 0157:H7 infection gens (eg, human immunodefi- can lead to the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, especially in chil- ciency virus [HIV], Escherichia dren; it also can cause thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. coli 0157:H7, hepatitis C) and a Chlamydia pneumoniae causes a mild pneumonia that resem- resurgence of old diseases pre- bles mycoplasmal pneumonia. Bacillary angiomatosis primar- sumed to be under control (eg, ily affects immunocompromised patients, especially those tuberculosis, syphilis). Further, infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At least multiple-drug resistance in two organisms can cause bacillary angiomatosis: Bartonella hense- strains of pneumococci, gono- lae and Bartonella quintana. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cocci, enterococci, staphylo- is spread by exposure to the droppings of infected rodents. cocci, salmonella, and mycobac- Contrary to previous thought, HIV continues to replicate teria undermines efforts to throughout the course of the illness and does not have a latency control the diseases they cause.2 phase. -

If Needed You Can Use Two Lines

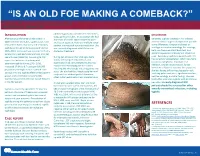

“IS AN OLD FOE MAKING A COMEBACK?” •Eyob Tadesse MD1; Samie Meskele MD1; Ankoor Biswas MD1 •Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee WI. NTRODUCTION abdomen gradually spread to her extremities, DISCUSSION I scalp, palms and soles. In association she had After being on the verge of elimination in shortness of breath, vague abdominal pain Generally, syphilis presents in HIV infected 2000 in the United States, syphilis cases have and loss of appetite, history of multiple sexual patients similar to general population yet with rebounded. Rates of primary and secondary partner, unprotected sex and prostitution. She some differences. Diagnosis is based on syphilis continued to increase overall during was recently diagnosed with HIV but not serologic test and microbiology. For serology, 2005–2013. Increases have occurred primarily started on treatment. both non treponemal antibody test, and among men, and particularly among men has specific treponemal antibody test should be used. Secondary syphilis in patients with HIV sex with men (MSM)(1). According to CDC During her admission her vital signs were has varied skin presentation, which can mimic report the incidence of primary and stable, she had pale conjunctivae, skin cutaneous lymphoma, mycobacterial secondary syphilis during 2015–2016, examination had demonstrated widespread macular and maculopapular skin lesions infection, bacillary angiomatosis, fungal increased 17.6% to 8.7 cases per 100,000 infections or Kaposi’s sarcoma. In our patient, population, the highest rate reported since involving the whole body including palms and soles. She also had thin, fragile scalp hair and she was having diffuse maculopapular rash, 1993(2). HIV and syphilis affect similar patient scalp hair loss without genital ulceration; involving palms and soles, significant hair loss, groups and co-infection is common(3). -

Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals in the Qaidam

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China Huaxiang Rao1, Shoujiang Li3, Liang Lu4, Rong Wang3, Xiuping Song4, Kai Sun5, Yan Shi3, Dongmei Li4* & Juan Yu2* Investigation of the prevalence and diversity of Bartonella infections in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China, could provide a scientifc basis for the control and prevention of Bartonella infections in humans. Accordingly, in this study, small mammals were captured using snap traps in Wulan County and Ge’ermu City, Qaidam Basin, China. Spleen and brain tissues were collected and cultured to isolate Bartonella strains. The suspected positive colonies were detected with polymerase chain reaction amplifcation and sequencing of gltA, ftsZ, RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) and ribC genes. Among 101 small mammals, 39 were positive for Bartonella, with the infection rate of 38.61%. The infection rate in diferent tissues (spleens and brains) (χ2 = 0.112, P = 0.738) and gender (χ2 = 1.927, P = 0.165) of small mammals did not have statistical diference, but that in diferent habitats had statistical diference (χ2 = 10.361, P = 0.016). Through genetic evolution analysis, 40 Bartonella strains were identifed (two diferent Bartonella species were detected in one small mammal), including B. grahamii (30), B. jaculi (3), B. krasnovii (3) and Candidatus B. gerbillinarum (4), which showed rodent-specifc characteristics. B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain (accounted for 75.0%). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii in the Qaidam Basin, might be close to the strains isolated from Japan and China. -

HIV and the SKIN • Sudden Acute Exacerbations • Treatment Failure DR

2018/08/13 KEY FEATURES • Atypical presentation of common disorders • Severe or exaggerated presentations HIV AND THE SKIN • Sudden acute exacerbations • Treatment failure DR. FREDAH MALEKA DERMATOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA:KALAFONG VIRAL INFECTIONS EXANTHEM OF PRIMARY HIV INFECTION • Exanthem of primary HIV infection • Acute retroviral syndrome • Herpes simplex virus (HSV) • Morbilliform rash (exanthem) : 2-4 weeks after HIV exposure • Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) • Typically generalised • Molluscum contagiosum (Poxvirus) • Pronounced on face and trunk, sparing distal extremities • Human papillomavirus (HPV) • Associated : fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis • Epstein Barr virus (EBV) • DDX: drug reaction • Cytomegalovirus (CMV) • other viral infections – EBV, Enteroviruses, Hepatitis B virus 1 2018/08/13 HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS(HSV) • Vesicular eruption due to HSV 1&2 • Primary lesion: painful, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base • HIV: attacks are more frequent and severe • : chronic, non-healing, deep ulcers, with scarring and tissue destruction • CLUE: severe pain and recurrences • DDX: syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum • Tzanck smear, Histology, Viral culture HSV • Treatment: Acyclovir 400mg tds 7-10 days • Alternatives: Valacyclovir and Famciclovir • In setting of treatment failure, viral isolates tested for resistance against acyclovir • Alternative drugs: Foscarnet, Cidofovir • Chronic suppressive therapy ( >8 attacks per year) 2 2018/08/13 VARICELLA • Chickenpox • Presents with erythematous papules and umbilicated -

Novel Small Rnas Expressed by Bartonella Bacilliformis Under Multiple Conditions 2 Reveal Potential Mechanisms for Persistence in the Sand Fly Vector and Human 3 Host

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.04.235903; this version posted August 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Novel small RNAs expressed by Bartonella bacilliformis under multiple conditions 2 reveal potential mechanisms for persistence in the sand fly vector and human 3 host 4 5 6 Shaun Wachter1, Linda D. Hicks1, Rahul Raghavan2 and Michael F. Minnick1* 7 8 9 10 1 Program in Cellular, Molecular & Microbial Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, 11 University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, United States of America 12 2 Department of Biology and Center for Life in Extreme Environments, Portland State 13 University, Portland, Oregon, United States of America 14 15 16 17 * Corresponding author 18 E-mail: [email protected] (MFM) 19 20 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.04.235903; this version posted August 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 21 Abstract 22 Bartonella bacilliformis, the etiological agent of Carrión’s disease, is a Gram-negative, 23 facultative intracellular alphaproteobacterium. Carrión’s disease is an emerging but neglected 24 tropical illness endemic to Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. B. bacilliformis is spread between 25 humans through the bite of female phlebotomine sand flies. -

09 Piqueras.Qxp

PERSPECTIVES INTERNATIONAL MICROBIOLOGY (2007) 10:217-226 DOI: 10.2436/20.1501.01.30 ISSN: 1139-6709 www.im.microbios.org Microbiology: a dangerous profession? Mercè Piqueras President, Catalan Association for Science Communication (ACCC), Barcelona, Spain The history of science contains many cases of researchers eases in Minorca from the year 1744 to 1749 to which is pre- who have died because of their professional activity. In the fixed, a short account of the climate, productions, inhabi- field of microbiology, some have died or have come close to tants, and endemical distempers of that island (T. Cadell, D. death from infection by agents that were the subject of their Wilson and G. Nicol, London, 1751), which he dedicated to research (Table 1). Infections that had a lethal outcome were the Society of Surgeons of His Majesty’s Royal Navy. usually accidental. Sometimes, however, researchers inocu- Minorcan historian of science Josep M. Vidal Hernández has lated themselves with the pathogen or did not take preventive described and carefully analyzed Cleghorn’s work in measures against the potential pathogen because they wanted Minorca and his report [43]. According to Vidal, what to prove their hypotheses—or disprove someone else’s— Cleghorn describes is “tertian” fever, which was the name regarding the origin of the infection. Here is an overview of given at the time to fever caused by malaria parasites with a several episodes in the history of microbiology since the mid periodicity of 48 hours. In fact, Cleghorn used quinine to nineteenth century involving researchers or workers in fields treat tertian fever (i.e, malaria), which was not eradicated related to microbiology who have become infected. -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Abstract Pultorak, Elizabeth Lauren

ABSTRACT PULTORAK, ELIZABETH LAUREN. The Epidemiology of Lyme Disease and Bartonellosis in Humans and Animals. (Under the direction of Edward B. Breitschwerdt). The expansion of vector borne diseases in humans, a variety of mammalian hosts, and arthropod vectors draws attention to the need for enhanced diagnostic techniques for documenting infection in hosts, effective vector control, and treatment of individuals with associated diseases. Through improved diagnosis of vector-borne disease in both humans and animals, epidemiological studies to elucidate clinical associations or spatio-temporal relationships can be assessed. Veterinarians, through the use of the C6 peptide in the SNAP DX test kit, may be able to evaluate the changing epidemiology of borreliosis through their canine population. We developed a survey to evaluate the practices and perceptions of veterinarians in North Carolina regarding borreliosis in dogs across different geographic regions of the state. We found that veterinarians’ perception of the risk of borreliosis in North Carolina was consistent with recent scientific reports pertaining to geographic expansion of borreliosis in the state. Veterinarians should promote routine screening of dogs for Borrelia burgdorferi exposure as a simple, inexpensive form of surveillance in this transitional geographic region. We next conducted two separate studies to evaluate Bartonella spp. bacteremia or presence of antibodies against B. henselae, B. koehlerae, or B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii in 296 patients examined by a rheumatologist and 192 patients with animal exposure (100%) and recent animal bites and scratches (88.0%). Among 296 patients examined by a rheumatologist, prevalence of antibodies (185 [62%]) and Bartonella spp. bacteremia (122 [41.1%]) was high. -

Bartonella Henselae • Fleas and Black-Legged Ticks (Also Called Deer Ticks) of the Genus Ixodes May Serve As Vectors, but This Has Not Disease Agent: Been Proven

APPENDIX 2 Bartonella henselae • Fleas and black-legged ticks (also called deer ticks) of the genus Ixodes may serve as vectors, but this has not Disease Agent: been proven. • Bartonella henselae Blood Phase: Disease Agent Characteristics: • Agent found in endothelial cells and associated with RBCs in symptomatic cases • Gram-negative bacillus or coccobacillus, aerobic, • Occult bacteremia sometimes occurs in the absence nonmotile, nonspore-forming, facultatively intracel- of specific antibodies. lular bacterium • Order: Rhizobiales; Family: Bartonellaceae Survival/Persistence in Blood Products: • Size: 0.3-0.6 ¥ 0.3-1.0 mm • Nucleic acid: Approximately 1900 kb of DNA • A spiking study suggests that B. henselae added to RBCs can be recovered on solid media through 35 Disease Name: days of storage at 4°C. • Cat scratch disease • Cat scratch fever Transmission by Blood Transfusion: • Bacillary angiomatosis • Theoretical • Bacillary peliosis Cases/Frequency in Population: Priority Level: • 22,000 cases per year estimated in the US • Scientific/Epidemiologic evidence regarding blood • 2-6% in US blood donors safety: Theoretical • Cumulative seroprevalence of 7.1% to B. henselae and • Public perception and/or regulatory concern regard- B. quintana in US veterinary professionals ing blood safety: Absent • Public concern regarding disease agent: Very low Incubation Period: Background: • 3-10 days to appearance of papule at inoculation site; regional adenopathy may follow after a few weeks • In 1909,ALBartondescribed organisms that adhered to RBCs. Likelihood of Clinical Disease: • The name Bartonella bacilliformis was used for the • Relatively benign and self-limiting, lasting 6-12 weeks only member of the group identified before 1993. in the absence of antibiotic therapy • Several other species of Bartonella are known to infect humans, but at present, B. -

Bacillary Angiomatosis with Bone Invasion*

CASE REPORT 811 s Bacillary angiomatosis with bone invasion* Lucia Martins Diniz1 Karina Bittencourt Medeiros1 Luana Gomes Landeiro1 Elton Almeida Lucas1 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165436 Abstract: Bacillary angiomatosis is an infection determined by Bartonella henselae and B. quintana, rare and prevalent in pa- tients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. We describe a case of a patient with AIDS and TCD4+ cells equal to 9/mm3, showing reddish-violet papular and nodular lesions, disseminated over the skin, most on the back of the right hand and third finger, with osteolysis of the distal phalanx observed by radiography. The findings of vascular proliferation with presence of bacilli, on the histopathological examination of the skin and bone lesions, led to the diagnosis of bacillary angiomatosis. Corroborating the literature, in the present case the infection affected a young man (29 years old) with advanced immunosup- pression and clinical and histological lesions compatible with the diagnosis. Keywords: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; Angiomatosis, bacillary; Bartonella; Bartonella quintana INTRODUCTION Histology of the lesions of affected organs shows vascular Bacillary angiomatosis is an infection universally distrib- proliferation, hence the name “angiomatosis”. By silver staining, the uted, rare, caused by Gram-negative and facultative intracellular presence of the bacilli is revealed, thus “bacillary”.4 In histological bacilli of the Bartonella genus, which 18 species and subspecies are description, capillary proliferation is observed characteristically in currently known, and which also determine other diseases in man.1 lobes – central capillaries are more differentiated and peripheral The species responsible for bacillary angiomatosis are B. henselae capillaries are less mature – with lumens not so evident. -

Detection and Partial Molecular Characterization of Rickettsia and Bartonella from Southern African Bat Species

Detection and partial molecular characterization of Rickettsia and Bartonella from southern African bat species by Tjale Mabotse Augustine (29685690) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER SCIENTIAE (MICROBIOLOGY) in the Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria, South Africa Supervisor: Dr Wanda Markotter Co-supervisors: Prof Louis H. Nel Dr Jacqueline Weyer May, 2012 I declare that the thesis, which I hereby submit for the degree MSc (Microbiology) at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, is my own work and has not been submitted by me for a degree at another university ________________________________ Tjale Mabotse Augustine i Acknowledgements I would like send my sincere gratitude to the following people: Dr Wanda Markotter (University of Pretoria), Dr Jacqueline Weyer (National Institute for Communicable Diseases-National Health Laboratory Service) and Prof Louis H Nel (University of Pretoria) for their supervision and guidance during the project. Dr Jacqueline Weyer (Centre for Zoonotic and Emerging diseases (Previously Special Pathogens Unit), National Institute for Communicable Diseases (National Heath Laboratory Service), for providing the positive control DNA for Rickettsia and Dr Jenny Rossouw (Special Bacterial Pathogens Reference Unit, National Institute for Communicable Diseases-National Health Laboratory Service), for providing the positive control DNA for Bartonella. Dr Teresa Kearney (Ditsong Museum of Natural Science), Gauteng and Northern Region Bat Interest Group, Kwa-Zulu Natal Bat Interest Group, Prof Ara Monadjem (University of Swaziland), Werner Marias (University of Johannesburg), Dr Francois du Rand (University of Johannesburg) and Prof David Jacobs (University of Cape Town) for collection of blood samples.