Elk Smith Project Preliminary Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the California's 2001 Wildfire

RECOMMENDED CITATION FORMAT Blonksi, K.S., M.E. Morales, and T.J. Morales. 2002. Proceedings of the California’s 2001 Wildfire Conference: Ten Years After the East Bay Hills Fire; October 10-12, 2001; Oakland California. Technical Report 35.01.462. Richmond CA: University of California Forest Products Laboratory. Key words: East Bay Hill’s fire, fire modeling, fire analysis, community planning/permitting, fire behavior, vegetation management, fuels management, Hills Emergency Forum, incident perspectives, homeowners’ hazards, insurance Published by: University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources Forest Products Laboratory 1301 South 46th Street, Richmond, CA 94804 www.ucfpl.ucop.edu Edited by: Tony Morales and Maria Morales Safe Solutions Group P.O. 2463 Berkeley CA, 94702 510-486-1056 [email protected] Special thanks to: Miriam Aroner for comments & Ariel Power for technical suggestions. Proceedings of the California’s 2001 Wildfire Conference: 10 Years After the 1991 East Bay Hills Fire SPECIAL RECOGNITION GOES TO OUR SUPPORTERS FOR THEIR DONATION OF TIME, MONEY AND SERVICES Sponsors: Bureau of Land Management California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection California Fire Alliance Diablo Fire Safe Council East Bay Regional Park District Federal Emergency Management Agency, Region IX (FEMA) Governor’s Office of Emergency Services Hills Emergency Forum Insurance Services Offices Inc. (ISO) Jack London Square Merritt College Environmental Science Program North Tree Fire International Port of Oakland Safeco Insurance -

Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation

Report on the Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation Report on the Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation August 2013 Prepared by: Chi Ho Sham, Mary Ellen Tuccillo, and Jaime Rooke The Cadmus Group, Inc. 100 5th Ave., Suite 100 Waltham, MA 02451 Jointly Sponsored by: Water Research Foundation 6666 West Quincy Avenue, Denver, CO 80235-3098 and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, D.C. Published by: [Insert WaterRF logo] DISCLAIMER This study was jointly funded by the Water Research Foundation (Foundation) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). The Foundation and USEPA assume no responsibility for the content of the research study reported in this publication or for the opinions or statements of fact expressed in the report. The mention of trade names for commercial products does not represent or imply the approval or endorsement of either the Foundation or USEPA. This report is presented solely for informational purposes Copyright © 2013 by Water Research Foundation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise utilized without permission. ISBN [inserted by the Foundation] Printed in the U.S.A. CONTENTS DISCLAIMER.............................................................................................................................. iv CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................. -

9 Canaday Hill Rd. Berne, NY 1290 SR 143 Coeymans Hollow, NY 145

Albany County 9 Canaday Hill Rd. (518) 728-8025 26-Apr Berne, NY Berne Volunteer Fire Company 1290 SR 143 756-6310 27-Apr Coeymans Hollow, NY Coeymans Hollow Volunteer Fire Corp. 145 Adams Street 518-475-7310 26-Apr Delmar , NY Delmar Fire Department 25 Main St (518) 728-8025 26-Apr East Berne, NY East Berne Volunteer Fire Company 15 West Poplar Dr (518) 439-9144 27-Apr Delmar, NY Elsmere Fire Dept 15 West Poplar Dr April 26- 5184399144 Delmar, NY 27 Elsmere Fire Dept 1342 Central Ave. April 26- 518-489-4421 Colonie, NY 27 Fuller Road Fire Department 30 School Road (518) 861-8871 26-Apr Guilderland Center, NY Guilderland Center Volunteer Fire Department 2303 Western Ave 518-456-5000 26-Apr Guilderland, NY Guilderland Fire Department 2198 Berne Altamont RD (518) 728-8025 26-Apr Knox Volunteer Fire Company Knox, NY 1250 Western Ave April 26- (518)-489-4340 Albany, NY 27 McKownville Fire Department 28 County Route 351 518-872-0368 26-Apr Medusa, NY Medusa Volunteer Fire Company 1956 Central Avenue Midway Fire Department 5184561424 27-Apr Midway Fire Department 5184561424 27-Apr Albany, NY 694 New Salem Road (518) 765-2231 26-Apr Voorheesville, NY New Salem Volunteer Fire Department 2178 Tarrytown Rd (518) 728-8025 26-Apr Clarksville, NY Onesquethaw Volunteer Fire Company 4885 State RD 85 Rensselaerville Volunteer Fire Department (518) 966-0338 27-Apr Rensselaerville, NY 900 1st Street Schuyler Heights (518)271-7851 26-Apr Watervliet , NY 301 glenmont rd April 26- Selkirk 518-728-5831 Glenmont, NY 27 550 Albany Shaker Road 518-458-1352 26-Apr Loudonville, NY Shaker Road Loudonville Fire Department P.O. -

Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 1

Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 1 Running head: COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE IN EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT: SOCIAL MEDIA’S ROLE IN THE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management: Social Media's Emerging Role in the Emergency Operations Center Eric D. Nickel Novato Fire District Novato, California Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 2 CERTIFICATION STATEMENT I hereby certify that this paper constitutes my own product, that where the language of others is set forth, quotation marks so indicate, and that appropriate credit is given where I have used the language, ideas, expressions, or writings of another. Signed: __________________________________ Collective Intelligence in Emergency Management 3 ABSTRACT The problem was that the Novato Fire District did not utilize social media technology to gather or share intelligence during Emergency Operations Center activations. The purpose of this applied research project was to recommend a social media usage program for the Novato Fire District’s Emergency Operations Center. Descriptive methodology, literature review, two personal communications and a statistical sampling of fire agencies utilizing facebook supported the research questions. The research questions included what were collective intelligence and social media; how was social media used by individuals and organizations during events and disasters; how many fire agencies maintained a facebook page and used them to distribute emergency information; and which emergency management social media programs should be recommended for the Novato Fire District’s Emergency Operations Center. The procedures included two data collection experiments, one a statistical sampling of United States fire agencies using facebook, to support the literature review and research questions. This research is one of the first Executive Fire Officer Applied Research Projects that addressed this emerging subject. -

Dudleyas Burned Landscapes in the Sierra Nevada Forest

$5.00 (Free to Members) VOL. 42, NO. 3 • SEPTEMBER 2014 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DUDLEYASDUDLEYAS BURNEDBURNED LANDSCAPESLANDSCAPES ININ THETHE SIERRASIERRA NEVADANEVADA FORESTFOREST RESILIENCERESILIENCE FOLLOWINGFOLLOWING WILDFIREWILDFIRE VOL. 42, NO. 3, SEPTEMBER 2014 FREMONTIA CARECARE OFOF NATIVENATIVE OAKSOAKS V42.3_cover.final.pmd 1 8/13/14, 12:19 PM CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5130 FREMONTIA Phone: (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Fax: (916) 447-2727 Web site: www.cnps.org Email: [email protected] VOL. 42, NO. 3, SEPTEMBER 2014 MEMBERSHIP Copyright © 2014 Membership form located on inside back cover; California Native Plant Society dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the CNPS Bulletin Mariposa Lily . $1,500 Family or Group . $75 Bob Hass, Editor Benefactor . $600 International or Library . $75 Patron . $300 Individual . $45 Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $25 Ileene Anderson, Brad Jenkins, and Mary Ann Showers, Proofreaders CORPORATE/ORGANIZATIONAL 10+ Employees . $2,500 4-6 Employees . $500 7-10 Employees . $1,000 1-3 Employees . $150 CALIFORNIA NATIVE STAFF – SACRAMENTO CHAPTER COUNCIL PLANT SOCIETY Executive Director: Dan Gluesenkamp David Magney (Chair); Larry Levine Finance and Administration (Vice Chair); Marty Foltyn (Secretary) Dedicated to the Preservation of Manager: Cari Porter Membership and Development Alta Peak (Tulare): Joan Stewart the California Native Flora Coordinator: Stacey Flowerdew -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Marin County Fire Department in collaboration with COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN 2016 Cover photo, istock.com, copyright David Safanda, 2007. ● ● ● Executive Summary Executive Summary This Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) provides a scientifically based assessment of wildfire threat in the wildland urban interface (WUI) of Marin County, California. This CWPP was developed through a collaborative process involving Marin County fire agencies, county officials, county, state, and federal land management agencies, and community members. It meets the CWPP requirements set forth in the federal Healthy Forests Restoration Act, which include: • Stakeholder collaboration (Section 3). • Identifying and prioritizing areas for fuel reduction activities (Sections 4 and 5). • Addressing structural ignitability (Section 7). Wildfire poses the greatest risk to human life and property in Marin County’s densely populated WUI, which holds an estimated 69,000 living units. Marin County is home to 23 communities listed on CAL FIRE’s Communities at Risk list, with approximately 80% of the total land area in the county designated as having moderate to very high fire hazard severity ratings. The county has a long fire history with many large fires over the past decades, several of which have occurred in the WUI. To compound the issue, national fire suppression policies and practices have contributed to the continuous growth (and overgrowth) of vegetation resulting in dangerous fuel loads (see Section 1.6). ● ● ● i ● ● ● Executive Summary A science-based hazard, asset, risk assessment was performed using up-to-date, high resolution topography and fuels information combined with local fuel moisture and weather data. The assessment was focused on identifying areas of concern throughout the county and beginning to prioritize areas where wildfire threat is greatest. -

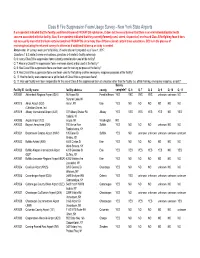

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey

Class B Fire Suppression Foam Usage Survey - New York State Airports If a respondent indicated that the facility used/stored/disposed PFOA/PFOS substances, it does not necessarily mean that there is an environmental/public health concern associated with that facility. Also, if a respondent indicated that they currently/formerly used, stored, disposed of, or released Class B firefighting foam it does not necessarily mean that the foam contains/contained PFOA/PFOS since many Class B foams do not contain these substances. DEC is in the process of reviewing/evaluating the returned surveys to determine if additional follow-up or study is needed. Return rate: 91 surveys were sent to facilities; 90 were returned completed as of June 1, 2017. Questions 1 & 2 relate to name and address; questions 3-5 relate to facility ownership. Q. 6: Is any Class B fire suppression foam currently stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 7: Has any Class B fire suppression foam ever been stored and/or used at the facility? Q. 8: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for training purposes at the facility? Q. 9: Has Class B fire suppression foam ever been used for firefighting or other emergency response purposes at the facility? Q. 10: Has the facility ever experienced a spill or leak of Class B fire suppression foam? Q. 11: Has your facility ever been responsible for the use of Class B fire suppression foam at a location other than the facility (i.e. offsite training, emergency response, or spill)? Survey Facility ID facility name facility address county complete? Q. -

OCR Document

FIRST -HAND ACCOUNTS OF THE MOUNT VISION FIRE BY A RANCHER A FIREFIGHTER A PARK RANGER A FIRE STRATEGIST A FIRE WARDEN A WATER DISTRICT MANAGER INMATE FIREFIGHTERS AN OBSERVER HOME OWNERS BURNED OUT A HOMEOWNER SPARED A NATURALIST Interviews by Leonard Tennyson, Inverness Transcriptions by Lynne D.Yonng, Marshall and by Connie Holton, Berkeley. Copyright Leonard Tennyson Inverness, California 1996 Second Edition 1996 October 13,1996 ABOUT THE INTERVIEWS: These" oral history" interviews were made over a period of several months after the October '95 Mt. Vision fire. They were done at the suggestion of Louise Landreth, a member of the Committee of the Jack Mason Museum of Inverness, for the Museum's historical archives. These unabridged interviews barely scratch the surface. They reflect only the personal views and experiences of two dozen or so people whose lives were touched by the fire. Limits of time and resources eliminated scores of others -- people who played vital roles in fighting the fire and those whose lives were profoundly affected by it. Of the former group, many are well known through official reports. They include Park Superintendent Don Neubacher, Stan Rowan, Chief of the Marin County Fire Department, and Tom Tarp, the State's Fire Chief. Together they formed the triumvirate of the Incident Command. In the latter group must be included all of the people who lost their homes in the fire. We can never measure in full the contributions of the "unknowns" -- hand crew firefighters, engine crews, dozer operators, pilots and crews of helicopters and air tankers and providers of food and shelter. -

Lessons Learned 2017 North Bay Fire Siege September 2018

Lessons Learned 2017 North Bay Fire Siege September 2018 Prepared By: Marin County Fire Department P.O. Box 518, Woodacre, CA 94973 www.marincountyfire.org 1 Contents: Previous Steps in Fire Preparedness 3 Board of Supervisors Takes Action 6 Scope of Sub-Committee 8 Panel Interview (North Bay Officials) 8 Public Listening Session / Community Forum 11 Suggested Areas for Improvement 12 Next Steps / Recommendations 18 Contact Information 20 2 The devastating wildfires of the October 2017 North Bay Fire Siege left nearby communities frightened and highlighted the necessity for fire prevention and preparedness. When the fires started on October 8th, the only thing separating Marin County from their neighbors to the north was simply an ignition source. Subsequent community conversations regarding wildfire preparedness have highlighted the need to update Marin communities on preparation that is already underway as well as plans that local government has developed to prepare further. In November 2017, the Marin County Board of Supervisors created a sub-committee to study lessons learned from the North Bay Fires. The sub-committee included Supervisors Judy Arnold and Dennis Rodoni, leaders from fire, law enforcement, and land management agencies, as well as representatives from Marin’s cities and towns. The public was also invited to voice concerns and hear from the agencies represented. The sub-committee proceeded in three steps: first, the sub-committee held an extensive panel interview with Sonoma officials in order to learn from their experiences. Next, the sub-committee hosted a public forum in an effort to gather community input and preferences. Finally, the sub-committee took an inventory of Marin’s existing programs, identifying gaps within and across agencies. -

Fire Department Participation Report 2005

Fire Department Participation Report 2005 FDID Name JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC Total ALBANY COUNTY 01001 ALBANY FIRE 1,726 1,338 1,613 1,573 1,602 1,336 1,704 1,700 1,686 1,564 1,417 1,506 18765 DEPARTMENT 01002 ALTAMONT FIRE 16 7 10 12 9 14 10 18 8 13 6 14 137 DEPARTMENT 01003 BERNE FIRE 3 5 4 12 2 9 5 6 4 16 10 8 84 DEPARTMENT 01004 BOUGHT COMMUNITY 17 8 14 20 17 35 12 15 17 28 12 13 208 FIRE DEPT 01005 COEYMANS FIRE 30 5 9 14 4 6 13 10 7 8 10 11 127 DEPARTMENT 01006 COEYMANS-HOLLOW NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR NR 0 FIRE DEPT 01007 COHOES FIRE 273 209 231 211 191 267 252 235 219 258 210 197 2753 DEPARTMENT 01008 COLONIE FIRE 28 22 22 24 27 28 13 30 19 30 21 24 288 DEPARTMENT 01009 DELMAR FIRE 23 17 12 20 21 31 33 34 28 29 35 34 317 DEPARTMENT Note "NR" indicates that no incidents were reported for that month. Organizations appearing in red submitted no incidents for the entire reporting period. 7/9/2007 Page 1 of 185 Fire Department Participation Report 2005 FDID Name JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC Total 01010 ELSMERE FIRE 22 14 22 22 27 36 37 28 26 31 37 25 327 DEPARTMENT 01011 FORT HUNTER FIRE 20 13 20 15 19 24 18 20 20 13 11 26 219 DEPT 01012 FULLER ROAD FIRE 71 37 39 67 65 59 51 86 60 76 73 83 767 DEPARTMENT 01013 GREEN ISLAND FIRE 43 27 46 37 59 49 40 49 43 55 9 38 495 DEPT 01014 GUILDERLAND FIRE 24 13 25 17 16 23 17 26 25 17 18 24 245 DEPARTMENT 01015 GUILDERLAND 21 11 12 15 7 18 10 22 6 13 6 18 159 CENTER FIRE DEPT 01016 KNOX FIRE 1 6 7 12 3 8 5 9 2 8 7 5 73 DEPARTMENT 01017 LATHAM FIRE 68 51 43 65 50 69 68 40 46 80 55 52 687 DEPARTMENT 01018 MEDUSA FIRE 2 3 4 2 1 3 3 1 3 1 1 2 26 DEPARTMENT 01019 MAPLEWOOD FIRE NR NR NR NR NR 3 19 14 18 18 1 NR 73 DEPARTMENT Note "NR" indicates that no incidents were reported for that month. -

Belmont Foster City San Mateo

Belmont ▪Foster City ▪San Mateo 2017 Annual Report Photo from December 2017 Thomas Fire Deployment, Ventura CA Table of Contents 2017 Annual Report Mission Statements 3 Message from the Chief 4 Organization Chart 5 Fire Stations 6 Budget 7 Station Platoon Roster 8 San Mateo County Fire Academy 10 New Hires 13 Promotions 14 Retirements 16 Significant Incidents & Rescues 18 Mutual Aid Response 20 Department Stats 22 Fire Personnel Residences 23 Training 24 Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) 25 Office of Emergency Services 28 Community Outreach 30 Bureau of Fire Protection & Life Safety 32 2 Belmont ~ Foster City ~ San Mateo 2017 Annual Report Mission Statements Belmont Fire Department Mission Statement It is the mission of the Belmont Fire Department to; preserve life, property, and the environment as an all risk emergency services provider. Core Values Professionalism ▪ Dedication ▪ Teamwork ▪ Respect ▪ Ethical Behavior ▪ Compassion ▪ Honesty ▪ Integrity Foster City Fire Department Mission Statement The Fire Department protects lives, property and the environment from fire and exposure to hazardous materials, provides pre-hospital emergency medical care, offers programs which prepare our employees and citizens for emergencies and provides non-emergency services, including fire prevention and related code enforcement, emergency preparedness and fire prevention to residents, businesses and visitors of Foster City. Core Values Service to the Community: Delivering the highest level of service to our customers during emergency operations, citizen assists and public education programs. Integrity: Maintaining high ethical standards and treating customers and all Department members with dignity. Striving through deeds to earn the trust and respect of others. Dedication: Demonstrating loyalty to our organization and seeking and supporting continued education, training opportunities and ways to create ongoing improvement within our mission. -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan

MARIN COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN DECEMBER 2020 Marin County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared by Prepared for Tami L. Lavezzo Chief, Jason Weber Bryan M. Penfold Battalion Chief, Christie Neill ShihMing M. Huang Charles R. Scarborough Marin County Fire Department 33 Castle Rock Ave. Sonoma Technology Woodacre CA 94973 1450 N. McDowell Blvd., Suite 200 415.473.6717 Petaluma, CA 94954 marincounty.org/depts/fr Ph 707.665.9900 | F 707.665.9800 sonomatech.com December 2020 This document contains blank pages to accommodate two-sided printing. ● ● ● Contents Contents Figures ...........................................................................................................................................................................................v Tables ........................................................................................................................................................................................... vi 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Stakeholders and Collaboration .............................................................................................. 3 2.1 Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority .............................................................................................................. 4 2.1.1 Ecologically Sound Practices Partnership ..................................................................................... 4 2.2 FIRESafe MARIN ....................................................................................................................................................