2017 Marin County Unit Strategic Fire Plan & Community Wildfire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fireboat Is Needed for Halifax Port

B2 TheChronicle Herald BUSINESS Wednesday,February20, 2019 Counsel appointed to represent Quadriga users ANDREA GUNN millions lost in cash and crypto- creditors have been congregating Airey is among many that pany and the court appointed OTTAWA BUREAU currency when the company’s on online forums, mainly Reddit believe something criminal is at monitor attempted to locate the founder and CEO died suddenly and Twitter. play, and is organizing the protest funds. [email protected] in December. “There are more than 100,000 to bring attention to the need for But some blockchain analysts @notandrea Three teams of lawyers had affected users. They range from an investigation. have reported little evidence of initially made apitch to represent small creditors who are owed Airey said he’s concerned that the cold wallets the company Nova Scotia Supreme Court creditors, but Wood’s decision $100, to others who are owed the court is not sufficiently claims are inaccessible, while Justice Michael Wood has ap- identified the selected council as many millions. Privacy is agreat equipped to deal with such a others have been trying to find pointed two law firms to repres- the best positioned for the job. concern and many users do not highly technical case. evidence of possible criminal ent some 115,000 users owed $250 “Both the local and national wish to be publicly identified in “The judge didn’t even know activity on the blockchain that can million by Canadian cryptocur- firms have extensive insolvency any fashion,” Wood wrote. what Reddit was, let alone the be tied to Quadriga’s wallets — rency exchange QuadrigaCX. -

Meet the Seattle Fire Boat Crew the Seattle Fire Department Has a Special Type of Fire Engine

L to R: Gregory Anderson, Richard Chester, Aaron Hedrick, Richard Rush Meet the Seattle fire boat crew The Seattle Fire Department has a special type of fire engine. This engine is a fire boat named Leschi. The Leschi fire boat does the same things a fire engine does, but on the water. The firefighters who work on the Leschi fire boat help people who are sick or hurt. They also put out fires and rescue people. There are four jobs for firefighters to do on the fire boat. The Pilot drives the boat. The Engineer makes sure the engines keep running. The Officer is in charge. Then there are the Deckhands. Engineer Chester says, “The deckhand is one of the hardest jobs on the fire boat”. The deckhands have to be able to do everyone’s job. Firefighter Anderson is a deckhand on the Leschi Fireboat. He even knows how to dive under water! Firefighter Anderson says, “We have a big job to do. We work together to get the job done.” The whole boat crew works together as a special team. The firefighters who work on the fire boat practice water safety all the time. They have special life jackets that look like bright red coats. Officer Hedrick says, “We wear life jackets any time we are on the boat”. The firefighters who work on the fire boat want kids to know that it is important to be safe around the water. Officer Hedrick says, “Kids should always wear their life jackets on boats.” Fishing for Safety The firefighters are using binoculars and scuba gear to find safe stuff under water. -

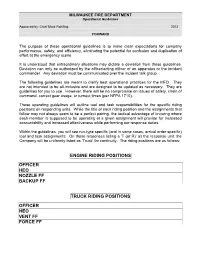

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

A 29 Unit Multifamily Investment Opportunity Located in Sausalito, CA the LEESON GROUP Exclusively Listed By

CLICK HERE FOR PROPERTY VIDEO A 29 Unit Multifamily Investment Opportunity Located in Sausalito, CA THE LEESON GROUP Exclusively Listed By: THE LEESON GROUP ERICH M. REICHENBACH TYLER C. LEESON First Vice President Senior Managing Director 415-625-2146 714-713-9086 [email protected] [email protected] CA License: 01860626 CA License: 01451551 MATTHEW J. KIPP First Vice President 949-419-3254 [email protected] CA License: 01364032 DANIEL E. RABIN ASHLEY A. BAILEY Director of Operations Senior Transaction Manager 949-419-3306 949-419-3219 [email protected] [email protected] www.TheLeesonGroup.com www.TheLeesonGroup.com ANDREW M. PISES ALLISON M. DAVIS Marketing Coordinator Marketing Coordinator 949-419-3266 949-419-3208 [email protected] [email protected] www.TheLeesonGroup.com www.TheLeesonGroup.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 20 26 32 Executive Summary Property Overview Financial Analysis Market Comparables SPECIAL COVID-19 NOTICE All potential buyers are strongly advised to take advantage of their opportunities and obligations to conduct thorough due diligence and seek expert opinions as they may deem necessary, especially given the unpredictable changes resulting from the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. Marcus & Millichap has not been retained to perform, and cannot conduct, due diligence on behalf of any prospective purchaser. Marcus & Millichap’s principal expertise is in marketing investment properties and acting as intermediaries between buyers and sellers. Marcus & Millichap and its investment professionals cannot and will not act as lawyers, accountants, contractors, or engineers. All potential buyers are admonished and advised to engage other professionals on legal issues, tax, regulatory, financial, and accounting matters, and for questions involving the property’s physical condition or financial outlook. -

HOW FRANK LLOYD Wrighr CAME to MARIN COONIY, CALIFORNIA, .AND GLORIFIED SAN RAFAEL

__.. __.0- __._. __.... __,_... ~ .. ~ _ ... __._ ~ __.. ,. __ "I I 73-5267 RADFORD, Evelyn Emerald Morris, 1921- THE GENIUS .AND THE COONIY BUILDING: HOW FRANK LLOYD WRIGHr CAME TO MARIN COONIY, CALIFORNIA, .AND GLORIFIED SAN RAFAEL. University of Hawaii, Ph.D., 1972 Political Science, general University Microfilms. A XEROX Company. Ann Arbor. Michigan @ 1972 EVELYN EMERALD MORRIS RADFORD ALL RIGHrS RESERVED ----------- ; THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED • ' .~: - THE GENIUS AND THE COUNTY BUILDING: HOW FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT CAME TO MARIN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, AND GLORIFIED SAN RAFAEL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIl IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES AUGUST 1972 By Evelyn Morris Radford Dissertation Committee: Reuel Denney, Chairman James McCutcheon J. Meredith Neil Murray Turnbull Aaron Levine Seymour Lutzky PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company iii PREFACE Marin County has been written about as a place where charming Indian legends abound, where misty beauty evokes a breathless appreciation of natural wonders, where tales of the sea are told around cozy hearths, and where nostalgia for the old California of Mexican hidalgos and an exotic array of inter national characters finds responsive audience. Even today the primary interests of Marin chroniclers center on old settlers, their lives and their fortunes, and the exotic polyglot of ethnic groups that came to populate the shores of the waters that wash Marin. This effort to analyze by example some of the social processes of Marin is in large part an introductory effort. -

Historical Status of Coho Salmon in Streams of the Urbanized San Francisco Estuary, California

CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME California Fish and Game 91(4):219-254 2005 HISTORICAL STATUS OF COHO SALMON IN STREAMS OF THE URBANIZED SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY, CALIFORNIA ROBERT A. LEIDY1 U. S. Environmental Protection Agency 75 Hawthorne Street San Francisco, CA 94105 [email protected] and GORDON BECKER Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration 4179 Piedmont Avenue, Suite 325 Oakland, CA 94611 [email protected] and BRETT N. HARVEY Graduate Group in Ecology University of California Davis, CA 95616 1Corresponding author ABSTRACT The historical status of coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, was assessed in 65 watersheds surrounding the San Francisco Estuary, California. We reviewed published literature, unpublished reports, field notes, and specimens housed at museum and university collections and public agency files. In watersheds for which we found historical information for the occurrence of coho salmon, we developed a matrix of five environmental indicators to assess the probability that a stream supported habitat suitable for coho salmon. We found evidence that at least 4 of 65 Estuary watersheds (6%) historically supported coho salmon. A minimum of an additional 11 watersheds (17%) may also have supported coho salmon, but evidence is inconclusive. Coho salmon were last documented from an Estuary stream in the early-to-mid 1980s. Although broadly distributed, the environmental characteristics of streams known historically to contain coho salmon shared several characteristics. In the Estuary, coho salmon typically were members of three-to-six species assemblages of native fishes, including Pacific lamprey, Lampetra tridentata, steelhead, Oncorhynchus mykiss, California roach, Lavinia symmetricus, juvenile Sacramento sucker, Catostomus occidentalis, threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus, riffle sculpin, Cottus gulosus, prickly sculpin, Cottus asper, and/or tidewater goby, Eucyclogobius newberryi. -

Latitude 38'S Guide to Bay Sailing

MayCoverTemplate 4/21/09 9:51 AM Page 1 Latitude 38 VOLUME 383 May 2009 WE GO WHERE THE WIND BLOWS MAY 2009 VOLUME 383 BAYGUIDE SAILING TO BAY SAILINGGUIDE Is there anyone out there who's worth of learning the hard way into one and is worth a pass. Stay in the channel not feeling the pinch of the recession? grand tour of the Bay done in style and though, as the northeast side is shallow We doubt it. And yes, many are feeling comfort. We call it the The Perfect Day- and the bottom is riddled with debris. more than a pinch. We're reminded of sail, and it goes like this... Sailing back out the Sausalito Chan- the advice of Thomas Jefferson: "When Start anywhere east of Alcatraz about nel, hug the shoreline and enjoy the you get to the end of your rope, tie a 11 a.m., at which time the fog is begin- Mediterranean look of southern Sau- knot and hang on!" ning to burn off and a light breeze is fill- salito. Generally, the closer you stay to Speaking of ropes and knots and ing in. You're going to be sailing coun- this shore, the flukier the wind — until hanging on, while the 'suits' rage from terclockwise around the Bay, so from you get to Hurricane Gulch. It's not shore while the economy struggles to Alcatraz, head around the backside of marked on the charts, but you'll know extricate itself from the tarpit — we Angel Island and sail west up Raccoon when you're there. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Although much of the San Francisco Bay Region is densely populated and industrialized, many thousands of acres within its confines have been set aside as parks and preserves. Most of these tracts were not rescued until after they had been altered. The construction of roads, the modification of drainage patterns, grazing by livestock, and the introduction of aggressive species are just a few of the factors that have initiated irreversible changes in the region’s plant and animal life. Yet on the slopes of Mount Diablo and Mount Tamal- pais, in the redwood groves at Muir Woods, and in some of the regional parks one can find habitats that probably resemble those that were present two hundred years ago. Even tracts that are far from pristine have much that will bring pleasure to those who enjoy the study of nature. Visitors to our region soon discover that the area is diverse in topography, geology, cli- mate, and vegetation. Hills, valleys, wetlands, and the seacoast are just some of the situa- tions that will have one or more well-defined assemblages of plants. In this manual, the San Francisco Bay Region is defined as those counties that touch San Francisco Bay. Reading a map clockwise from Marin County, they are Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco. This book will also be useful in bordering counties, such as Mendocino, Lake, Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito, because many of the plants dealt with occur farther north, east, and south. For example, this book includes about three-quarters of the plants found in Monterey County and about half of the Mendocino flora. -

Biology Report

MEMORANDUM Scott Batiuk To: Lynford Edwards, GGBHTD From: Plant and Wetland Biologist [email protected] Date: June 13, 2019 Verification of biological conditions associated with the Corte Madera 4-Acre Tidal Subject: Marsh Restoration Project Site, Professional Service Agreement PSA No. 2014- FT-13 On June 5, 2019, a WRA, Inc. (WRA) biologist visited the Corte Madera 4-Acre Tidal Marsh Restoration Project Site (Project Site) to verify the biological conditions documented by WRA in a Biological Resources Inventory (BRI) report dated 2015. WRA also completed a literature review to confirm that special-status plant and wildlife species evaluations completed in 2015 remain valid. Resources reviewed include the California Natural Diversity Database (California Department of Fish and Wildlife 20191), the California Native Plant Society’s Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (California Native Plant Society 20192), and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Information for Planning and Consultation database (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 20193). Biological Communities In general, site conditions are similar to those documented in 2015. The Project Site is a generally flat site situated on Bay fill soil. A maintained berm is present along the western and northern boundaries. Vegetation within the Project Site is comprised of dense, non-native species, characterized primarily by non-native grassland dominated by Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica) and pampas grass (Cortaderia spp.). Dense stands of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) are present in the northern and western portions on the Project Site. A small number of seasonal wetland depressions dominated by curly dock (Rumex crispus), fat hen (Atriplex prostrata) and brass buttons (Cotula coronopifolia) are present in the northern and western portions of the Project Site, and the locations and extent of wetlands observed are similar to what was documented in 2015. -

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department

A Brief History of the Charlotte Fire Department The Volunteers Early in the nineteenth century Charlotte was a bustling village with all the commercial and manufacturing establishments necessary to sustain an agrarian economy. The census of 1850, the first to enumerate the residents of Charlotte separately from Mecklenburg County, showed the population to be 1,065. Charlotte covered an area of 1.68 square miles and was certainly large enough that bucket brigades were inadequate for fire protection. The first mention of fire services in City records occurs in 1845, when the Board of Aldermen approved payment for repair of a fire engine. That engine was hand drawn, hand pumped, and manned by “Fire Masters” who were paid on an on-call basis. The fire bell hung on the Square at Trade and Tryon. When a fire broke out, the discoverer would run to the Square and ring the bell. Alerted by the ringing bell, the volunteers would assemble at the Square to find out where the fire was, and then run to its location while others would to go the station, located at North Church and West Fifth, to get the apparatus and pull it to the fire. With the nearby railroad, train engineers often spotted fires and used a special signal with steam whistles to alert the community. They were credited with saving many lives and much property. The original volunteers called themselves the Hornets and all their equipment was hand drawn. The Hornet Company purchased a hand pumper in 1866 built by William Jeffers & Company of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. -

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST and MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE

Vegetation Descriptions NORTH COAST AND MONTANE ECOLOGICAL PROVINCE CALVEG ZONE 1 December 11, 2008 Note: There are three Sections in this zone: Northern California Coast (“Coast”), Northern California Coast Ranges (“Ranges”) and Klamath Mountains (“Mountains”), each with several to many subsections CONIFER FOREST / WOODLAND DF PACIFIC DOUGLAS-FIR ALLIANCE Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is the dominant overstory conifer over a large area in the Mountains, Coast, and Ranges Sections. This alliance has been mapped at various densities in most subsections of this zone at elevations usually below 5600 feet (1708 m). Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) is a common conifer associate in some areas. Tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. densiflorus) is the most common hardwood associate on mesic sites towards the west. Along western edges of the Mountains Section, a scattered overstory of Douglas-fir often exists over a continuous Tanoak understory with occasional Madrones (Arbutus menziesii). When Douglas-fir develops a closed-crown overstory, Tanoak may occur in its shrub form (Lithocarpus densiflorus var. echinoides). Canyon Live Oak (Quercus chrysolepis) becomes an important hardwood associate on steeper or drier slopes and those underlain by shallow soils. Black Oak (Q. kelloggii) may often associate with this conifer but usually is not abundant. In addition, any of the following tree species may be sparsely present in Douglas-fir stands: Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), Ponderosa Pine (Ps ponderosa), Incense Cedar (Calocedrus decurrens), White Fir (Abies concolor), Oregon White Oak (Q garryana), Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum), California Bay (Umbellifera californica), and Tree Chinquapin (Chrysolepis chrysophylla). The shrub understory may also be quite diverse, including Huckleberry Oak (Q. -

Proceedings of the California's 2001 Wildfire

RECOMMENDED CITATION FORMAT Blonksi, K.S., M.E. Morales, and T.J. Morales. 2002. Proceedings of the California’s 2001 Wildfire Conference: Ten Years After the East Bay Hills Fire; October 10-12, 2001; Oakland California. Technical Report 35.01.462. Richmond CA: University of California Forest Products Laboratory. Key words: East Bay Hill’s fire, fire modeling, fire analysis, community planning/permitting, fire behavior, vegetation management, fuels management, Hills Emergency Forum, incident perspectives, homeowners’ hazards, insurance Published by: University of California Agriculture & Natural Resources Forest Products Laboratory 1301 South 46th Street, Richmond, CA 94804 www.ucfpl.ucop.edu Edited by: Tony Morales and Maria Morales Safe Solutions Group P.O. 2463 Berkeley CA, 94702 510-486-1056 [email protected] Special thanks to: Miriam Aroner for comments & Ariel Power for technical suggestions. Proceedings of the California’s 2001 Wildfire Conference: 10 Years After the 1991 East Bay Hills Fire SPECIAL RECOGNITION GOES TO OUR SUPPORTERS FOR THEIR DONATION OF TIME, MONEY AND SERVICES Sponsors: Bureau of Land Management California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection California Fire Alliance Diablo Fire Safe Council East Bay Regional Park District Federal Emergency Management Agency, Region IX (FEMA) Governor’s Office of Emergency Services Hills Emergency Forum Insurance Services Offices Inc. (ISO) Jack London Square Merritt College Environmental Science Program North Tree Fire International Port of Oakland Safeco Insurance