Prokaryotic Cell Structure & Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Pili in Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria – Structure

Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66 (2009) 613 – 635 1420-682X/09/040613-23 Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences DOI 10.1007/s00018-008-8477-4 Birkhuser Verlag, Basel, 2008 Review Pili in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria – structure, assembly and their role in disease T. Profta,c,* and E. N. Bakerb,c a School of Medical Sciences, Department of Molecular Medicine & Pathology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142 (New Zealand), Fax: +64-9-373-7492, e-mail: [email protected] b School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland (New Zealand) c Maurice Wilkins Centre for Molecular Biodiscovery, University of Auckland (New Zealand) Received 08 August 2008; received after revision 24 September 2008; accepted 01 October 2008 Online First 27 October 2008 Abstract. Many bacterial species possess long fila- special form of bacterial cell movement, known as mentous structures known as pili or fimbriae extend- twitching motility. In contrast, the more recently ing from their surfaces. Despite the diversity in pilus discovered pili in Gram-positive bacteria are formed structure and biogenesis, pili in Gram-negative bac- by covalent polymerization of pilin subunits in a teria are typically formed by non-covalent homopo- process that requires a dedicated sortase enzyme. lymerization of major pilus subunit proteins (pilins), Minor pilins are added to the fiber and play a major which generates the pilus shaft. Additional pilins may role in host cell colonization. be added to the fiber and often function as host cell This review gives an overview of the structure, adhesins. Some pili are also involved in biofilm assembly and function of the best-characterized pili formation, phage transduction, DNA uptake and a of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. -

Prokaryotes (Domains Bacteria & Archaea)

2/4/15 Prokaryotes (Domains Bacteria & Archaea) KEY POINTS 1. Decomposers: recycle organic and inorganic molecules in environment; makes them available to other organisms. 2. Essential components of symbioses. 3. Encompasses the origins of metabolism and metabolic diversity. 4. Origin of photosynthesis and formation of atmospheric Oxygen Ceno- Meso- zoic zoic ANTIQUITY Humans Paleozoic Colonization of land Animals Origin of solar system and Earth • >3.5 BILLION years old. • Alone for 2 1 4 billion years Proterozoic Archaean Prokaryotes Billions of 2 years ago3 Multicellular eukaryotes Single-celled eukaryotes Atmospheric oxygen General characteristics 1. Small: compare to 10-100µm for 0.5-5µm eukaryotic cell; single-celled; may form colonies. 2. Lack membrane- enclosed organelles. 3. Cell wall present, but different from plant cell wall. 1 2/4/15 General characteristics 4. Occur everywhere, most numerous organisms. – More individuals in a handful of soil then there are people that have ever lived. – By far more individuals in our gut than eukaryotic cells that are actually us. General characteristics 5. Metabolic diversity established nutritional modes of eukaryotes. General characteristics 6. Important decomposers and recyclers 2 2/4/15 General characteristics 6. Important decomposers and recyclers • Form the basis of global nutrient cycles. General characteristics 7. Symbionts!!!!!!! • Parasites • Pathogenic organisms. • About 1/2 of all human diseases are caused by Bacteria General characteristics 7. Symbionts!!!!!!! • Parasites • Pathogenic organisms. • Extremely important in agriculture as well. Pierce’s disease is caused by Xylella fastidiosa, a Gamma Proteobacteria. It causes over $56 million in damage annually in California. That’s with $34 million spent to control it! = $90 million in California alone. -

Structural and Functional Characterization of the Fimh Adhesin of Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli and Its Novel Applications

Open Access Journal of Bacteriology and Mycology Research Article Structural and Functional Characterization of the FimH Adhesin of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Its Novel Applications Neamati F1, Moniri R2*, Khorshidi A1 and Saffari M1 Abstract 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, School Type 1 fimbriae are responsible for bacterial pathogenicity and biofilm of Medicine, Kashan University of Medical Sciences, production, which are important virulence factors in uropathogenic Escherichia Kashan, Iran coli strains. Many articles are published on FimH, but each examined a specific 2Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, aspect of this protein. The current review study aimed at focusing on structure Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Qutb Ravandi and conformational changes and describing efforts to use this protein in novel Boulevard, Kashan, Iran potential treatments for urinary tract infections, typing methods, and expression *Corresponding author: Moniri R, Department of systems. The current study was the first review that briefly and effectively Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kashan University of examined issues related to FimH adhesin. Medical Sciences, Qutb Ravandi Boulevard, Kashan, Iran Keywords: Uropathogenic E. coli; FimH Adhesion; FimH Typing; Received: June 05, 2020; Accepted: July 03, 2020; Conformation Switch; FimH Antagonists Published: July 10, 2020 Abbreviations FimH proteins play important roles in UPEC pathogenicity and the formation of bacterial biofilms [7]. FimH binds to mannosylated UTIs: Urinary Tract Infections; UPEC: Uropathogenic E. uroplakin proteins in the bladder lumen and invades into the Coli; IBCs: Intracellular Bacterial Communities; QIR: Quiescent superficial umbrella cells [8]. After the invasion, UPEC is expelled out Intracellular Reservoir; LD: Mannose-Binding Lectin; PD: Fimbria- of the cell in a TLR4 dependent process, or escape into the cytoplasm Incorporating Pilin; MBP: Mannose-Binding Pocket; LIBS: Ligand- [9]. -

A Generic Large-Scale Cause for Platelet Dysfunction and Depletion in Infection

Published online: 2020-04-12 THIEME 302 A Champion of Host Defense: A Generic Large-Scale Cause for Platelet Dysfunction and Depletion in Infection Martin J. Page, BSc (Hons)1 Etheresia Pretorius, PhD1 1 Department of Physiological Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Address for correspondence Etheresia Pretorius, PhD, Department of Stellenbosch, South Africa Physiological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1 Matieland, Stellenbosch, 7602, South Africa Semin Thromb Hemost 2020;46:302–319. (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Thrombocytopenia is commonly associated with sepsis and infections, which in turn are characterized by a profound immune reaction to the invading pathogen. Platelets are one of the cellular entities that exert considerable immune, antibacterial, and antiviral actions, and are therefore active participants in the host response. Platelets are sensitive to surrounding inflammatory stimuli and contribute to the immune response by multiple mechanisms, including endowing the endothelium with a proinflammatory phenotype, enhancing and amplifying leukocyte recruitment and inflammation, promoting the effector functions of immune cells, and ensuring an optimal adaptive immune response. During infection, pathogens and their products influence the platelet response and can even be toxic. However, platelets are able to sense and engage bacteria and viruses to assist in their removal and destruction. Platelets greatly contribute to host defense by multiple mechanisms, including forming immune complexes and aggregates, shedding their granular content, and internalizing pathogens and subsequently being marked for removal. These processes, and the nature of platelet function in general, cause the platelet to be irreversibly consumed in Keywords the execution of its duty. An exaggerated systemic inflammatory response to infection ► platelets can drive platelet dysfunction, where platelets are inappropriately activated and face ► virus immunological destruction. -

The First Cells Were Most Likely Very Simple Prokaryotic Forms. Ra- Spirochetes

T HE O RIGIN OF E UKARYOTIC C ELLS The first cells were most likely very simple prokaryotic forms. Ra- spirochetes. Ingestion of prokaryotes that resembled present-day diometric dating indicates that the earth is 4 to 5 billion years old cyanobacteria could have led to the endosymbiotic development of and that prokaryotes may have arisen more than 3.5 billion years chloroplasts in plants. ago. Eukaryotes are thought to have first appeared about 1.5 billion Another hypothesis for the evolution of eukaryotic cells proposes years ago. that the prokaryotic cell membrane invaginated (folded inward) to en- The eukaryotic cell might have evolved when a large anaerobic close copies of its genetic material (figure 1b). This invagination re- (living without oxygen) amoeboid prokaryote ingested small aerobic (liv- sulted in the formation of several double-membrane-bound entities ing with oxygen) bacteria and stabilized them instead of digesting them. (organelles) in a single cell. These entities could then have evolved This idea is known as the endosymbiont hypothesis (figure 1a) and into the eukaryotic mitochondrion, nucleus, and chloroplasts. was first proposed by Lynn Margulis, a biologist at Boston Univer- Although the exact mechanism for the evolution of the eu- sity. (Symbiosis is an intimate association between two organisms karyotic cell will never be known with certainty, the emergence of of different species.) According to this hypothesis, the aerobic bac- the eukaryotic cell led to a dramatic increase in the complexity and teria developed into mitochondria, which are the sites of aerobic diversity of life-forms on the earth. At first, these newly formed eu- respiration and most energy conversion in eukaryotic cells. -

Vocabulario De Morfoloxía, Anatomía E Citoloxía Veterinaria

Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) Servizo de Normalización Lingüística Universidade de Santiago de Compostela COLECCIÓN VOCABULARIOS TEMÁTICOS N.º 4 SERVIZO DE NORMALIZACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA VOCABULARIO de morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria : (galego-español- inglés) / coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río, Servizo de Normalización Lingüística ; autores Matilde Lombardero Fernández ... [et al.]. – Santiago de Compostela : Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, 2008. – 369 p. ; 21 cm. – (Vocabularios temáticos ; 4). - D.L. C 2458-2008. – ISBN 978-84-9887-018-3 1.Medicina �������������������������������������������������������������������������veterinaria-Diccionarios�������������������������������������������������. 2.Galego (Lingua)-Glosarios, vocabularios, etc. políglotas. I.Lombardero Fernández, Matilde. II.Rodríguez Rio, Xusto A. coord. III. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística, coord. IV.Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, ed. V.Serie. 591.4(038)=699=60=20 Coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río (Área de Terminoloxía. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela) Autoras/res Matilde Lombardero Fernández (doutora en Veterinaria e profesora do Departamento de Anatomía e Produción Animal. -

Identification of Type 3 Fimbriae in Uropathogenic Escherichia Coli

JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Feb. 2008, p. 1054–1063 Vol. 190, No. 3 0021-9193/08/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/JB.01523-07 Copyright © 2008, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Identification of Type 3 Fimbriae in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Reveals a Role in Biofilm Formationᰔ Cheryl-Lynn Y. Ong,1 Glen C. Ulett,1 Amanda N. Mabbett,1 Scott A. Beatson,1 Richard I. Webb,2 Wayne Monaghan,3 Graeme R. Nimmo,3 David F. Looke,4 1 1 Alastair G. McEwan, and Mark A. Schembri * Downloaded from School of Molecular and Microbial Sciences1 and Centre for Microscopy and Microanalysis,2 University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, and Queensland Health Pathology Service3 and Infection Management Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia4 Received 21 September 2007/Accepted 17 November 2007 Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is the most common nosocomial infection in the United States. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC), the most common cause of CAUTI, can form biofilms on indwelling catheters. Here, we identify and characterize novel factors that affect biofilm formation by UPEC http://jb.asm.org/ strains that cause CAUTI. Sixty-five CAUTI UPEC isolates were characterized for phenotypic markers of urovirulence, including agglutination and biofilm formation. One isolate, E. coli MS2027, was uniquely proficient at biofilm growth despite the absence of adhesins known to promote this phenotype. Mini-Tn5 mutagenesis of E. coli MS2027 identified several mutants with altered biofilm growth. Mutants containing insertions in genes involved in O antigen synthesis (rmlC and manB) and capsule synthesis (kpsM) possessed enhanced biofilm phenotypes. Three independent mutants deficient in biofilm growth contained an insertion in a gene locus homologous to the type 3 chaperone-usher class fimbrial genes of Klebsiella pneumoniae. -

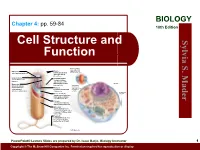

Cell Structure and Function

BIOLOGY Chapter 4: pp. 59-84 10th Edition Cell Structure and S. Sylvia Function Plasma membrane: outer surface that Ribosome: Fimbriae: regulates entrance site of protein synthesis hairlike bristles that and exit of molecules allow adhesion to Mader the surfaces Inclusion body: Conjugation pilus: stored nutrients for elongated, hollow later use appendage used for DNA transfer to other Nucleus: Mesosome: bacterial cells plasma membrane Cytoskeleton: maintains cell that folds into the Nucleoid: shape and assists cytoplasm and location of the bacterial movement of increases surface area chromosome cell parts: Endoplasmic Plasma membrane: reticulum: sheath around cytoplasm that regulates entrance and exit of molecules Cell wall: covering that supports, shapes, and protects cell Glycocalyx: gel-like coating outside cell wall; if compact, called a capsule; if diffuse, called a slime layer Flagellum: rotating filament present in some bacteria that pushes the cell forward *not in plant cells PowerPoint® Lecture Slides are prepared by Dr. Isaac Barjis, Biology Instructor 1 Copyright © The McGraw Hill Companies Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display Outline Cellular Level of Organization Cell theory Cell size Prokaryotic Cells Eukaryotic Cells Organelles Nucleus and Ribosome Endomembrane System Other Vesicles and Vacuoles Energy related organelles Cytoskeleton Centrioles, Cilia, and Flagella 2 Cell Theory Detailed study of the cell began in the 1830s A unifying concept in biology Originated from the work of biologists Schleiden and Schwann in 1838-9 States that: All organisms are composed of cells German botanist Matthais Schleiden in 1838 German zoologist Theodor Schwann in 1839 All cells come only from preexisting cells German physician Rudolph Virchow in 1850’s Cells are the smallest structural and functional unit of organisms 3 Organisms and Cells Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Killing of Gram-Negative Bacteria by Lactoferrin and Lysozyme

Killing of gram-negative bacteria by lactoferrin and lysozyme. R T Ellison 3rd, T J Giehl J Clin Invest. 1991;88(4):1080-1091. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI115407. Research Article Although lactoferrin has antimicrobial activity, its mechanism of action is not full defined. Recently we have shown that the protein alters the Gram-negative outer membrane. As this membrane protects Gram-negative cells from lysozyme, we have studied whether lactoferrin's membrane effect could enhance the antibacterial activity of lysozyme. We have found that while each protein alone is bacteriostatic, together they can be bactericidal for strains of V. cholerae, S. typhimurium, and E. coli. The bactericidal effect is dose dependent, blocked by iron saturation of lactoferrin, and inhibited by high calcium levels, although lactoferrin does not chelate calcium. Using differing media, the effect of lactoferrin and lysozyme can be partially or completely inhibited; the degree of inhibition correlating with media osmolarity. Transmission electron microscopy shows that E. coli cells exposed to lactoferrin and lysozyme at 40 mOsm become enlarged and hypodense, suggesting killing through osmotic damage. Dialysis chamber studies indicate that bacterial killing requires direct contact with lactoferrin, and work with purified LPS suggests that this relates to direct LPS-binding by the protein. As lactoferrin and lysozyme are present together in high levels in mucosal secretions and neutrophil granules, it is probable that their interaction contributes to host defense. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/115407/pdf Killing of Gram-negative Bacteria by Lactofernn and Lysozyme Richard T. Ellison III*" and Theodore J. Giehl *Medical and tResearch Services, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Division ofInfectious Diseases, Department ofMedicine, University ofColorado School ofMedicine, Denver, Colorado 80220 Abstract (4). -

A Double, Long Polar Fimbria Mutant of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Expresses Curli and Exhibits Reduced in Vivo Colonization

A Double, Long Polar Fimbria Mutant of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Expresses Curli and Exhibits Reduced in Vivo Colonization The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lloyd, Sonja J., Jennifer M. Ritchie, Maricarmen Rojas-Lopez, Carla A. Blumentritt, Vsevolod L. Popov, Jennifer L. Greenwich, Matthew K. Waldor, and Alfredo G. Torres. 2012. “A Double, Long Polar Fimbria Mutant of Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Expresses Curli and Exhibits ReducedIn VivoColonization.” Edited by S. M. Payne. Infection and Immunity 80 (3): 914–20. https://doi.org/10.1128/ iai.05945-11. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41483527 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Double, Long Polar Fimbria Mutant of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Expresses Curli and Exhibits Reduced In Vivo Colonization Sonja J. Lloyd,a Jennifer M. Ritchie,d* Maricarmen Rojas-Lopez,a Carla A. Blumentritt,a Vsevolod L. Popov,b Jennifer L. Greenwich,d Matthew K. Waldor,d and Alfredo G. Torresa,b,c Departments of Microbiology and Immunologya and Pathologyb and Sealy Center for Vaccine Development,c University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, Texas, USA, and Channing Laboratory, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USAd Escherichia coli O157:H7 causes food and waterborne enteric infections that can result in hemorrhagic colitis and life- threatening hemolytic uremic syndrome. -

Engineering the Human Microbiome, a Natural Double-Barreled Approach Towards Solving Both Our Current Antibiotic Resistance and Sepsis Problems

American Journal of www.biomedgrid.com Biomedical Science & Research ISSN: 2642-1747 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Opinion Copy Right@ Toleman MA Engineering the Human Microbiome, A Natural Double-Barreled Approach Towards Solving both our Current Antibiotic Resistance and Sepsis Problems Martins W1, Mathias J1, Babenko D2 and Toleman MA1* 1Cardiff University Medical school, Department of Immunology and Infection, The Heath hospital, UK 2Karaganda Medical University, Kazakhstan *Corresponding author: Toleman MA, Cardiff University Medical school, Department of Immunology and Infection, The Heath hospital, Cardiff, UK. To Cite This Article: Martins W, Mathias J, Babenko D, Toleman MA, Engineering the Human Microbiome, A Natural Double-Barreled Approach Towards Solving both our Current Antibiotic Resistance and Sepsis Problems. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2020 - 11(3). AJBSR.MS.ID.001632. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2020.11.001632. Received: December 12, 2020; Published: December 18, 2020 Opinion resistance mechanism responsible for this rise was an enzyme Many of the bacteria that cause life-threatening infection live called CTX-M-15 that gave resistance to the penicillin, monobactam, in very close association with us. Escherichia coli, for example and cephalosporin classes of the ß-lactam family of antibiotics (c. causes 80% of common community associated urinary tract infections and is also the main cause of serious (blood-stream) in several enteric pathogens including E. coli in New Delhi, India infection throughout Europe [1,2]. However, E. coli routinely lives 50% of all antibiotics) [7]. Its gene blaCTX-M-15 was first isolated in 2000 [8]. Later publications indicated that it was widespread as a commensal organism in our gut. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Mucosal Immunol

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Mucosal Immunol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 March 01. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Mucosal Immunol. 2013 March ; 6(2): 379–392. doi:10.1038/mi.2012.81. Molecular Organization of the Mucins and Glycocalyx Underlying Mucus Transport Over Mucosal Surfaces of the Airways Mehmet Kesimer*,‡,▫, Camille Ehre*, Kimberly A. Burns*, C. William Davis*,†, John K. Sheehan*,‡, and Raymond J. Pickles*,§ *Cystic Fibrosis/Pulmonary Research and Treatment Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7248 ‡Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7248 †Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7248 §Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7248 Abstract Mucus, with its burden of inspired particulates, and pathogens, is cleared from mucosal surfaces of the airways by cilia beating within the periciliary layer (PCL). The PCL is held to be ‘watery’ and free of mucus by thixotropic-like forces arising from beating cilia. With radii of gyration ~250 nm, however, polymeric mucins should reptate readily into the PCL, so we assessed the glycocalyx for barrier functions. The PCL stained negative for MUC5AC and MUC5B, but it was positive for keratan sulfate, a glycosaminoglycan commonly associated with glycoconjugates. Shotgun proteomics showed keratan sulfate-rich fractions from mucus containing abundant tethered mucins, MUC1, MUC4, and MUC16, but no proteoglycans. Immuno-histology by light and electron microscopy localized MUC1 to microvilli, MUC4 and MUC20 to cilia, and MUC16 to goblet cells.