Amanda Huron Interviewed by John Davis January 18, 2019 Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

T of À1 Radio

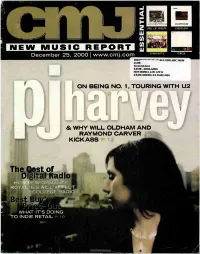

ism JOEL L.R.PHELPS EVERCLEAR ,•• ,."., !, •• P1 NEW MUSIC REPORT M Q AND NOT U CIRCLE December 25, 2000 I www.cmj.com 138.0 ******* **** ** * *ALL FOR ADC 90198 24498 Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS 5319 HONDA AVE APT G ATASCADERO, CA 93422-3428 ON BEING NO. 1, TOURING WITH U2 & WHY WILL OLDHAM AND RAYMOND CARVER KICK ASS tof à1 Radio HOW PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES WILL AFFECT COLLEGE RADIO WHAT IT'S DOING TO INDIE RETAIL INCLUDING THE BLAZING HIT SINGLE "OH NO" ALBUM IN STORES NOW EF •TARIM INEWELII KUM. G RAP at MOP«, DEAD PREZ PHARCIAHE MUNCH •GHOST FACE NOTORIOUS J11" MONEY PASTOR TROY Et MASTER HUM BIG NUMB e PRODIGY•COCOA BROVAZ HATE DOME t.Q-TIIP Et WORDS e!' le.‘111,-ZéRVIAIMPUIMTPIeliElrÓ Issue 696 • Vol 65 • No 2 Campus VVebcasting: thriving. But passion alone isn't enough 11 The Beginning Of The End? when facing the likes of Best Buy and Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office other monster chains, whose predatory ruled that FCC-licensed radio stations tactics are pricing many mom-and-pops offering their programming online are not out of business. exempt from license fees, which could open the door for record companies looking to 12 PJ Harvey: Tales From collect millions of dollars from broadcasters. The Gypsy Heart Colleges may be among the hardest hit. As she prepares to hit the road in support of her sixth and perhaps best album to date, 10 Sticker Shock Polly Jean Harvey chats with CMJ about A passion for music has kept indie music being No. -

The Weekly Arts End Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus Daily Nexus 2 a Thursday, January 11,1996

The Weekly Arts end Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus Daily Nexus 2 A Thursday, January 11,1996 Various Artists R ed H ot + B othered Red Hot/Kinetic/Reprise This is a review of a compilation of some of the truly underground music world’s fin est efforts. Just like Red Hot + Dance and Red Hot+Blue, Red Hot + Bothered is an album created to benefit AIDS research. Red Hot + Bothered is at least a few months old, but hey, I just got it so it’s new to me. Featured are a wide range of bands that well-represent “indie rock.” For all those who may not know what indie rock is, it’s music that’s put out through independent labels. However, there have been some large exceptions to this recently. Bands such as Jawbox, Royal Trux, Shudder to Think ana, earlier, Sonic Youth, who had been indie bands have signed to major labels. Being that they still have a raw, unproduced sound and that they are still highly respected by indie rockers, it’s not quite right to drop them from that indie-rock labeling. Another stranger and somewhat more glaring exception to this indie rock stuff is the fact that Red Hot+Bothered is on Reprise, which is a major label. The Red Hot people tried to hide this by putting the compilation out through the indie label Kinetic simulta neously. Oh well. So much for staying true to hardcore roots. So much for keeping it real. At least it’s for a good cause and the music is really good. -

Punk Rock History Project Update Punk Planet—The Collection Is Complete

This is MutantMutant PopPop free! Mailorder Catalog AH free! http://members.aol.com/mutantpop/ Hey, we rolled the odometer! Hooray for all of us! If I didn’t use the occasion to tweak the typography a little bit, i wouldn’t be doing my job. Thanks to Jeff Wison for the outstanding New Release Info dancing kids drawing, originally created for the the Pizzafest T-shirts. That cat can draw... As you can recall from MP Days of Yore, Pizzafest was gonna be a big show and pizzafeed with participants getting a free shirt, but the venue got paranoid about security, costs escalated, band avail- abilities got shaky, and the event was cancelled. Fortunately, it was replaced by not one but two “Mutant Fest” type of events: Cincinnati, OH in August (hosted by Dave Spodie of The Connie Dungs) and Columbus, OH in October (hosted by Eddie of The Proms). The bottom line is this: if you wanna have pop-punk events to attend this summer, people need to Do It Yourself. Get out there and independently organize your own Mutant Fest-type of deal! It would seem that there would be enough people and bands in the NY/NJ/PA area and possibly also in the Pacific Northwest—in addition to room for shows in the heartland of the pop-punk world, the midwest. There are rumors of a possible Connie Dungs/Dirt Bike Annie mini-tour this summer, how great would it be to tie into that? It’s something for you The 40th Mutant Pop 7”er is now on the street! people in pop-punk bands to think about—make your own fun! MP-39 THE BEAUTYS “A#1 Sex Shop Em- ployee” EP finally made it to my doorstep from Bill Smith Custom Records in LA on January 4. -

ISSUE 8, July, 2007

Out Of The Blue Sports Feature Motocross Local Zack Ames Exclusive Interviews Concert Coverage RevCo Shinedown Helmet MewithoutYou Anti-Flag Nine Inch Nails The Academy Is Warped Tour Less Than Jake Ministry Motion City Soundtrack Local Band Profiles, Columns, Album Reviews, Movie Reviews, Poetry Out Of The Blue Exclusive Interviews Band Profiles Concerts Sports Feature RevCo Hangtime Shinedown Helmet Animosity MewithoutYou Motocross Anti-Flag Scales of Emotion NIN, Bauhaus Local Less Than Jake Scene Of The Crime Warped Tour Zack Ames The Academy Is Project Defective Unknown Ministry Motion City Soundtrack Pietasters Indie Album Reviews, Indie Movie Reviews, Columns, Poetry, Art Out Of The Blue P.O. Box 388 Skate Park comes true for youth Delaware OH 43015 Delaware Battle Of The Bands 4 in the works www.myspace.com/ out_of_the_blue646 For a number of years Delaware, Ohio’s youth have been searching for a place to skate freely, without interjection from pointing fingers defying Publication Creators in 2001 their presence. Tiffany Cook Well, it has finally happened! Three consecutive Battle Of The Bands Neil Shumate (BOB) annual events, held at the Delaware County Fairgrounds, have con- tributed to Project Skate Park. Editor-in-Chief An entire 17,000 square feet dedicated to skating is being constructed Neil Shumate this summer. The 2006 BOB raised $4,100 in advance ticket sales, totaling $6,000 Copy Editor including raffle ticket John Shumate sales. An estimated 650 attended this Writers year’s event. Mike Couburn The ’06 BOB win- Josh Davis ners were Circleville’s Nick Messer Deaf Child Area, tak- Tony Rowe ing home $500; second Neil Shumate place was Grand Mar- John Shumate shall from Buckeye Valley High School, Columnists winning $150; and in Sagabu third place was the SINthetichead3000 yo ungest band— Unclassified from Layout and Design Delaware Willis Inter- Neil Shumate mediate, who took home a $100 prize. -

Paul Weller Wild Wood

The Venus Trail •Flying Nun-Merge Paul Weller Wild Wood PAUL WELLER Wild Wood •Go! Discs/London-PLG FAY DRIVE LIKE JEHU Yank Crime •Cargo-Interscope FRENTE! Marvin The Album •Mammoth-Atlantic VOL. 38 NO.7 • ISSUE #378 VNIJ! P. COMBUSTIBLE EDISON MT RI Clnlr SURE THING! MESSIAH INSIDE II The Grays On Page 3 I Ah -So-Me-Chat In Reggae Route ai DON'T WANT IT. IDON'T NEED IT. BUT ICAN'T STOP MYSELF." ON TOUR VITH OEPECHE MOUE MP.'i 12 SACRAMENTO, CA MAJ 14 MOUNTAIN VIEV, CA MAI' 15 CONCORD, CA MA,' 17 LAS, VEGAS, NV MAI' 18 PHOENIX, AZ Aff.q 20 LAGUNA HILLS, CA MAI 21 SAN BERNARDINO, CA MA,' 24 SALT LAKE CITY, UT NOTHING MA,' 26 ENGLEVOOD, CO MA,' 28 DONNER SPRINGS, KS MA.,' 29 ST. LOUIS, MO MP, 31 Sa ANTONIO, TX JUNE 1HOUSTON. TX JUNE 3 DALLAS, TX JUNE 5BILOXI, MS JUNE 8CHARLOTTE, NC JUNE 9ATLANTA, GA THE DEBUT TRACK ON COLUMBIA .FROM THE ALBUM "UNGOD ." JUNE 11 TILE ,' PARX, IL PROOUCED 81.10101 FRYER. REN MANAGEMENT- SIEVE RENNIE& LARRY TOLL. COLI MI-31% t.4t.,• • e I The Grays (left to right): Jon Brion, Jason Falkner, Dan McCarroll and Buddy Judge age 3... GRAYS On The Move The two started jamming together, along with the band's third songwriter two guys who swore they'd never be in aband again, Jason Falkner and Buddy Judge and drummer Dan McCarron. The result is Ro Sham Bo Jo Brion sure looked like they were having agreat time being in the Grays (Epic), arecord full of glorious, melodic tracks that owe as much to gritty at BGB's earlier this month. -

Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08 047 (01) FM.Qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page Ii

08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page i Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page ii Critical Media Studies Series Editor Andrew Calabrese, University of Colorado This series covers a broad range of critical research and theory about media in the modern world. It includes work about the changing structures of the media, focusing particularly on work about the political and economic forces and social relations which shape and are shaped by media institutions, struc- tural changes in policy formation and enforcement, technological transfor- mations in the means of communication, and the relationships of all these to public and private cultures worldwide. Historical research about the media and intellectual histories pertaining to media research and theory are partic- ularly welcome. Emphasizing the role of social and political theory for in- forming and shaping research about communications media, Critical Media Studies addresses the politics of media institutions at national, subnational, and transnational levels. The series is also interested in short, synthetic texts on key thinkers and concepts in critical media studies. Titles in the series Governing European Communications: From Unification to Coordination by Maria Michalis Knowledge Workers in the Information Society edited by Catherine McKercher and Vincent Mosco Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy: The Emergence of DIY by Alan O’Connor 08_047 (01) FM.qxd 2/4/08 3:31 PM Page iii Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy The Emergence of DIY Alan O’Connor LEXINGTON BOOKS A division of ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. -

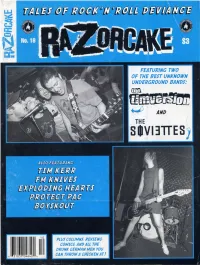

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #16 www.razorcake.com got up around 10am, after four hours of sleep. Someone falling After some Mexican food, and beer with fruit in it, Replay down the stairs woke me up. I skirted bodies littered in the front Dave, the really bendable bassist for Grabass Charlestons – who room and went for a glass of water. There was a small beer lake nights before, had landed into “a bed of the meanest cacti West II Texas has ever sprouted” then was arrested – chatted with me while on the kitchen floor. I grabbed the belt loops of the passed-out guy on the floor and scooched him out of the puddle. Wouldn't want I made some coffee. him to die in a quarter inch of beer. It was unfathomable that people “You forgot to ask some questions last night that were on your were still awake. I'd lasted until 6am. Some of the guys in the bands list,” he told me. The beer had gotten the better of my interviewing were shirtless, in the parking lot, and waving to the kids going to acumen. “Yeah, what'd I forget?” I asked. school. The bands I dig most tend to see touring as a vacation. “I never lived under an underpass. I lived under stairs until I I'll admit. I was a bit worried, until the sixth or seventh beer, got out of debt.” I'd found out that Dave, in a financial bind, that inviting thirteen plus people – Tiltwheel, The Tim Version, buckled down. -

County Body Approves Merger Plan Members of Public Enemy Inform

Drinking it in THE CHRONICLE CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 87, NO. 82 THURSDAY, JANUARY 30, 1992 © DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA County body approves merger plan By PEGGY KRENDL stand," said Deborah Giles, one of Strawbridge of the Friends of A standing ovation was the the county commissioners. Giles Durham, a conservative Durham answer to the county commission said the state could not legally political group. "There isn't any ers' unanimous decision to ap reject a proposal passed by a one in this room whose favorite prove the compromised election majority of county commission proposal this is." process for the merged school ers. The new 4-2-1 proposal calls The most opposition to the board. for four districts, each voting for a merger came from the Parents But not everyone was satisfied single member, two "super" dis for Better Schools which called with the result. tricts which would be composed for William Bell, chair of the The plan was a compromise of two of the four districts each county commissioners to resign between different proposals that and one at-large member who the for "losing trust and lacking lead wouldguaranteemmorityrepresen- entire county would elect. ership," said Steven Petry, mem tation and others that would not. "Any one plan would not have ber ofthe group. Petry said if the Between praise, insults, threats satisfied everyone or any group," county commissioners could not and charges that the commission said Ellen Reckhow, one of the do the job, than they should give ers were responsible for creating county commissioners. it up to some other government racial tensions in Durham, most of The county commissioners body. -

Bass, Vocals Darren Zentek: Drums DISCOGRAPHY Dischord

CHANNELS (2003- ) J. Robbins: Guitar, Vocals Janet Morgan: Bass, Vocals Darren Zentek: Drums DISCOGRAPHY Dischord # 151 “Waiting For The Next End of the World” CD 2006 Desoto # CH45 “Open” 6- song CDEP 2004 Bass guitar, electric guitar, voices and drums comprise a Rock Band. Sometimes other stuff gets thrown in there too, or subtracted, but that’s usually the essence of it. “Rock” is still occasionally open for definition, as it should be. Janet Morgan, J. Robbins, and Darren Zentek comprise Channels. It’s been a little over 20 years since these three were teenagers, and (despite growing up in different parts of the world) all trying gamely to comprehend the omnipresent threat of nuclear extinction via Mutually Assured Destruction as the Cold War shlepped on. Music was always good for mediating the tension then, opening the mind a little, helping to form those connections that made you feel less alone in your certainty that the world was completely insane. What would we all have done without punk rock (and its many bas- tard relations)? It’s tough enough just being a teenager without the End of the World in the frame. Anyway, a while later on things did seem to get better, everyone grew up to a greater or lesser extent, focus shifted, music and community held their allure, but the End of the World, reduced once more to a thought-provoking abstraction, sort of lost the limelight. Shame things couldn’t just stay that way. Still, it’s always been healthier to get things off your chest than to keep them bottled up. -

Dou Gas Iiiiii[

Vn1 YVTT NnH 15 T.av '.m Down. and Smack-em Yack-em Tune 24. 1996 •.•,•,:.::.:::,::.:·:·,,:::..::..:,,:,:.......•,,•::.,,~• iiiiiisi!!::; ;~~~~:·:·:·:·:·:·:.i.:..:.:!:· .!:··: ~:i:i:i:::::•..... ~~iiil~~~:::~f::::.... :·:·:....:-·i.:..•·· ' : ....· iii........... iii·:i j::·:·:··.................................... ii~~·:·:·:· ....•·:··:·:·:·ii;i:ii:·:i: •!:: i~~~~ii ....· :j:::::i~iii~iiiii, .:.:fi} .::.:.: ,,.:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: i·.··:·:'::.::.:.~. ... ·::::::::::::::::::::: .::::::::::::::::::::: · ·;' · ::~:::::::::::~i~i::s:::::::::::::·::i:::::::::: Dou g a:::!:?:?:i:i s iiiiii[,, i:?ii .·.·..·.·..·.·.:·.·.. irt ; ·:~·····.····'·· · ·-·· · ·.~ar.:1~~~~. m,.Pl~mn~;~~ P. O . D (" A n A d v e n t u r e in A c t i v i sm ) By Chris Sorochin must think we're either selling something or pimp- education, yet occupy some position in which oth- ing salvation. Ironically, many treated you like a ers must do as they say. He said it in such a way as Everyone who has the questionable honor of candidate for the lollipop factory if you take advan- to convey that he didn't really wish to help, so I sti- paying Federal Income Tax knows that on the tage of the political freedom everyone is supposed fled an urge to hand him some flyers and tell him to cover of the instruction booklet is a pie chart to be so high on. work the other end of the parking lot. He said we showing how our hard-earned national revenue is A Sears repairman refused information and mut- couldn't be on the property and would have to spent. The chart would have us believe that 22% ters, "They should give it all to the military", the move to the sidewalk. goes to the military. only negative reaction of the day. -

January 1995

Features PAUL WERTICO Pat Metheny's Paul Wertico is a bundle of contradictions: a highly exploratory drummer whose solo album is far from a chops-fest; a sophisticated accompanist who never took a lesson; a mainstream musician with avant-garde tendencies. Just who is this guy? Bill Milkowski 36 METAL DRUMMERS ROUND TABLE Away from the arenas and MTV cameras, today's top metal drummers have some serious issues to contend with—about the instrument they play and the business they're entangled in. Mike Portnoy, Deen Castronovo, Mark Zonder, Bobby Rock, Eric Singer, and John Tempesta cut to the chase. Matt Peiken 56 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? So you thought you'd never hear from the drummer in the Archies again—well, think again! Actually...we couldn't track him down.. .but we did get a hold of lots of your old faves— twenty-three of 'em, in fact. We think you might be surprised—and enlightened—by the stories they have to tell. Robyn Flans 76 Volume 19, Number 1 Cover Photo By Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 10 UPDATE 22 NEW AND PERSPECTIVES Black Sabbath's Bobby NOTABLE The Peart/Bozzio Rondinelli, Jay Schellen of Combination Challenge Sircle of Silence, BYRO B LEYTHAM Latin master Ignacio Berroa, and Jawbox's 102 ROCK 'N' Zach Barocas, plus News JAZZ CLINIC Hi-Hat Barks 133 INDUSTRY BY JOHN XEPOLEAS HAPPENINGS 1994 DCI World 104 LATIN Championship Results SYMPOSIUM BY LAUREN VOGELWEIS S The Soca BY RICH RYCHEL DEPARTMENTS 28 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP 106 UNDERSTANDING 4 EDITOR'S Yamaha Club RHYTHM OVERVIEW Custom Drumkit BY RICK VAN HORN Basic Reading: Part 2 BY HAL HOWLAND 6 READERS' 30 New Sabian Cymbals 110 STRICTLY PLATFORM BY RICK MATTINGLY TECHNIQUE 33 Evans Genera G2 The Sure-Fire 3:1 Cure 14 ASK A PRO Drumheads BY ED SHAUGHNESSY William Calhoun, BY RICK MATTINGLY David Garibaldi, 124 ARTIST ON and Blas Elias 114 SHOP TALK TRACK A Look At The GMS 16 IT'S Drum Company Jack DeJohnette BY ADAM BUDOFSKY BY MARK GRIFFITH QUESTIONABLE 126 CONCEPTS 120 CRITIQUE One Drummer's Psyche Vinnie Colaiuta and 112 SABIAN DREAM BY GLENN E.