Ravenscraig Green Network Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cashback for Communities

CashBack for Communities North Lanarkshire Local Authority 2015/16 About CashBack for Communities CashBack for Communities is a Scottish Government programme which takes funds recovered from the proceeds of crime and invests them into free activities and programmes for young people across Scotland. Inspiring Scotland is the delivery partner for the CashBack for Communities programme, appointed in July 2012. CashBack invests monies seized from criminals under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 back into our communities. Since 2008 the Scottish Government has committed £92 million to CashBack / community initiatives, funding community activities and facilities largely, but not exclusively, for young people. CashBack supports all 32 Local Authorities across Scotland. Sporting and recreational activities / culture / mentoring and employability / community projects. CashBack has delivered nearly 2 million activities and opportunities for young people. Phase 3 of CashBack runs to end March 2017 and is focused on positive outcomes for young people. CashBack for Communities: Aims CashBack activities: . Use the proceeds of crime in a positive way to expand young people’s horizons and increase their opportunities to develop their interests and skills in an enjoyable, fulfilling and supportive way. Are open, where possible, to all children and young people, while focusing resources in those communities suffering most from antisocial behaviour and crime. Seek to increase levels of participation to help divert young people away from ‘at risk’ behaviour, and will aim to increase the positive long-term outcomes for those who take part. Current CashBack Investment . Creative Scotland . YouthLink Scotland . Basketball Scotland . Celtic FC Foundation . Scottish Football Association . Youth Scotland . Scottish Rugby Union . -

Identification of Pressures and Impacts Arising Frm Strategic Development

Report for Scottish Environment Protection Agency/ Neil Deasley Planning and European Affairs Manager Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Environment Protection Agency Erskine Court The Castle Business Park Identification of Pressures and Impacts Stirling FK9 4TR Arising From Strategic Development Proposed in National Planning Policy Main Contributors and Development Plans Andrew Smith John Pomfret Geoff Bodley Neil Thurston Final Report Anna Cohen Paul Salmon March 2004 Kate Grimsditch Entec UK Limited Issued by ……………………………………………… Andrew Smith Approved by ……………………………………………… John Pomfret Entec UK Limited 6/7 Newton Terrace Glasgow G3 7PJ Scotland Tel: +44 (0) 141 222 1200 Fax: +44 (0) 141 222 1210 Certificate No. FS 13881 Certificate No. EMS 69090 09330 h:\common\environmental current projects\09330 - sepa strategic planning study\c000\final report.doc In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste or TCF (totally chlorine free) paper COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Report No: Contractor : Entec UK Ltd BACKGROUND The work was commissioned jointly by SEPA and SNH. The project sought to identify potential pressures and impacts on Scottish Water bodies as a consequence of land use proposals within the current suite of Scottish development Plans and other published strategy documents. The report forms part of the background information being collected by SEPA for the River Basin Characterisation Report in relation to the Water Framework Directive. The project will assist SNH’s environmental audit work by providing an overview of trends in strategic development across Scotland. MAIN FINDINGS Development plans post 1998 were reviewed to ensure up-to-date and relevant information. -

Holytown Surgery 43-45 Main Street Holytown ML1 4TH Tel: 01698

PLEASE NOTE THAT OUT OF HOURS CONTACT NUMBER IS CHANGING TO 111(FREE CALL) FROM 29TH APRIL 2014. Holytown Surgery Appointments Repeat prescriptions NHS Health Board Details Please bring your repeat prescription 43-45 Main Street An appointment is in operation in slip to the surgery allowing 48 hours NHS Lanarkshire HQ, Holytown our surgery. Please note: for completion. Kirklands Hospital Fallside Raod ML1 4TH One patient per appointment Alternatively you may post your Bothwell Urgent cases will always be request to the surgery always with a G71 8BB Tel: 01698 732463 accommodated. stamped addressed envelope. PH: 01698 855500 You may see any doctor in the Fax: 01698 732257 practice but it is better to see Patients may attend personally for Maternity Medical Services one doctor consistently. repeat prescriptions Ante Natal Children under 16 years should Post Natal Practice information: always be accompanied by a New patients: Family Planning responsible adult. All new patients are offered a check Cervical Smear and Well Women General Practitioners up on joining the practice and this Home visits service is also offered to all patients Childhood Immunisation / Dr M K Rao These should only be requested by between 16 – 75 years who have not Surveillance Dr S Raman patients who are too ill to travel to seen a doctor in the past 3 years. Elderly Screening the surgery. We would be grateful if Cardiac Disease Prevention you could phone before 10:30am to Over 74’s Asthma Practice Nurse enable your doctor to plan his We offer an annual check-up to all Diabetes rounds. -

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- A02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- a02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE Subject: COMMUNITY GRANTS SCHEME GRANTS TO PLAYSCHEMES - SUMMER 2001 JMcG/ Date: 12 SEPTEMBER 2001 Ref: BP/MF 1. PURPOSE 1.1 At its meeting of 15 May 2001 the community services (community development) sub committee agreed to fund playschemes operating during the summer period and in doing so agreed to apply the funding formula adopted in earlier years. The committee requested that details of the awards be reported to a future meeting. Accordingly these are set out in the appendix. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the committee: (i) note the contents of the appendix detailing grant awards to playschemes which operated during the summer 2001 holiday period. Community Grants Scheme - Playschemes 2001/2002 Playschemes Operating during Summer 2001 Loma McMeekin PSOl/O2 - 001 Bellshill Out of School Service Bellshill & surrounding area 10 70 f588.00 YMCA Orbiston Centre YMCA Orbiston Centre Liberty Road Liberty Road Bellshill Bellshill MU 2EU MM 2EU ~~ PS01/02 - 003 Cambusnethan Churches Holiday Club Irene Anderson Belhaven, Stewarton, 170 567.20 Cambusnethan North Church 45 Ryde Road Cambusnethan, Coltness, Kirk Road Wishaw Newmains Cambusnethan ML2 7DX Cambusnethan Old & Morningside Parish Church Greenhead Road Cambusnethan Mr. Mohammad Saleem PSO 1/02 - 004 Ethnic Junior Group North Lanarkshire 200 6 f77.28 Taylor High School 1 Cotton Vale Carfin Street Dalziel Park New Stevenston Motherwell. MLl 5NL PSO1102-006 Flowerhill Parish Church/Holiday -

North Lanarkshire Community Quiz

144 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: LEISURE SERVICES COMMITTEE Subject: NORTH LANARKSHIRE COMMUNITY QUIZ From: DIRECTOR OF LEISURE SERVICES Date: 4 August 1997 Ref AM/SR 1 Introduction The North Lanarkshre Community Quiz was launched at the Cultural Festival in 1996. The second annual quiz is now in progress and ths report provides background information. 2 Background 2.1 Eligibility Everyone who lives, works or studies in North Lanarkshre is eligible to enter. There are three categories:- Junior for those under 12 years; intermediate 12 - 18 years and an Adult Quiz Team. Each team comprises of 4 members and one reserve. 2.2 Distribution Posters and entq forms were sent directly to all schools, colleges, churches, sports facilities, libraries, community centres, health centres, various community groups, other Council departments and various local businesses. 2.3 Prizes The prizes sponsored by Askews Booksellers, Morley Books and Cawder Books are as follows:- (a) Book Tokens Winning Team Runners UP Adult 5150 5100 Intermediate 5100 5 75 Junior & 75 5 50 (b) The North Lanarkshre Community Quiz Trophy will be held for a year by the winners for each category. (c) Individual prizes to winning team members and runners-up of Adult dictionary or Intermediate Dictionary or Junior Reference Encyclopaedia as appropriate. L:DIRECTOR\COMMITTE\LEISCOhfMIQUIZ.CUL 145 (d) Individual certificates for team members reachmg quarter final, semi-final and final of Junior Quiz and final of Intermediate Quiz. 3 Uptake Entries were spread across North Lanarkshre, with the bulk of entries as would be expected received for junior and intermediate levels as follows:- Junior age group - 88 entries Intermediate Age Group 54 entries Adults 28 entries Appendix 1 lists the teams who have entered. -

Chief Officer Posts - March 1999

1 AGENDA lTEM No, NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL INFORMATION FOR APPLICANTS CHIEF OFFICER POSTS - MARCH 1999 North Lanarkshire stretches from Stepps to Harthill, from the Kilsyth Hills to the Clyde and includes, Airdrie, Bellshill, Coatbridge, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth, Motherwell, Shotts and Wishaw. With a population of over 326,000 it is one of the largest of Scotland’s local authorities. The Council aims to be caring, open and efficient, developing and providing opportunities for its people and communities in partnership with them and with all who can help to achieve its aims. The Council is the largest non-city unitary authority in Scotland and geographically is a mix of urban settlements with a substantial rural hinterland. The Council comprises the former authorities of Motherwell District Council; Monklands District Council; Cumbernauld and Kilsyth District Council; parts of 0 Strathkelvin District Council and parts of Strathclyde Regional Council. Rationalisation in the traditional industries of steel, coal and heavy engineering with attendant problems of unemployment, social deprivation and dereliction has led to concerted measures to regenerate the area and new investment and development programmes have been significant in the regeneration process. Organisationally, the Council has recently approved a management structure which updates the existing sound foundation, which emphasises the integration of policies and services and is designed to reflect the Council’s ambitions concerning best value, social inclusion, environmental sustainability and partnership and service delivery to the area’s communities As a consequence of the Council’s approval of this new structure, the Council now wishes to appoint experienced managers to fill certain new chief officer posts as set out in the accompanying Job Outline. -

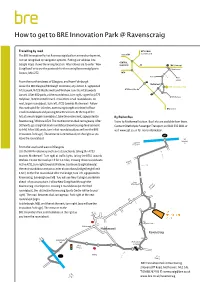

How to Get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig

How to get to BRE Innovation Park @ Ravenscraig Travelling by road M73 / M80 Airport M8 Cumbernauld The BRE Innovation Park at Ravenscraig is built on a new development, not yet recognised by navigation systems. Putting our address into CENTRAL Google maps shows the wrong location. Alternatives are to enter New GLASGOW A8 6 M8 Edinburgh Craig or to use the postcode for the nearby Ravenscraig Sports Newhouse ‘oad M74 Centre , ML1 2TZ. Bellshill A73 Lanark From the north and east of Glasgow, and from Edinburgh 5 Motherwell Leave the M8 Glasgow/Edinburgh motorway at junction 6, signposted BRE Innovation Park A73 Lanark /A723 Motherwell and Wishaw. Join the A73 towards A725 East Kilbride Lanark. After 400 yards, at the roundabout, turn right, signed to A775 6 A721 Wishaw Holytown /A723 to Motherwell. Cross three small roundabouts. At next, larger roundabout, turn left, A723 towards Motherwell. Follow this road uphill for 1.6 miles, continuing straight on at each of four M74 Carlisle small roundabouts and passing New Stevenson. At the top of the hill, at a much larger roundabout, take the second exit, signposted to By Rail or Bus Ravenscraig / Wishaw A721. The road becomes dual carriageway. After Trains to Motherwell station. Bus links are available from there. 300 yards, go straight at next roundabout (new housing development Contact Strathclyde Passenger Transport on 0141 332 6811 or to left). After 500 yards, turn left at roundabout (you will see the BRE visit www.spt.co.uk for more information. Innovation Park sign). The entrance is immediately on the right as you J6 leave the roundabout. -

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN POLICY DOCUMENT Local Development Plan Modified Proposed Plan Policy Document 2018

LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN POLICY DOCUMENT Local Development Plan Modified Proposed Plan Policy Document 2018 photo 2 Councillor Harry Curran, Planning Committee Convener The Local Development Plan sets out the Policies and Proposals to guide and meet North Lanarkshire’s development needs over the next 5-10 year. We want North Lanarkshire to be a place where The Local Development Plan policies identify the Through this Plan we will seek to ensure that the right everyone is given equality of opportunity, where development sites we need for sustainable and amount of development happens in the right places, individuals are supported, encouraged and cared for inclusive economic growth, sites we need to in a way that balances supply and demand for land at each key stage of their life. protect and enhance and has a more focussed uses, helps places have the infrastructure they need policy structure that sets out a clear vision for North without compromising the environment that defines North Lanarkshire is already a successful place, Lanarkshire as a place. Our Policies ensure that the them and makes North Lanarkshire a distinctive and making a significant contribution to the economy development of sites is appropriate in scale and successful place where people want to live, learn, of Glasgow City Region and Scotland. Our Shared character, will benefit our communities and safeguard work, invest and visit. Ambition, delivered through this Plan and our our environment. Economic Regeneration Delivery Plan, is to make it even more successful and we will continue to work with our partners and communities to deliver this Ambition. -

Coronation Park, New Stevenston

NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Subject: ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENTS COMMITTEE CORONATION PARK, NEW STEVENSTON. From: HEAD OF PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT Date: 6 JUNE 2007 Ref: DPT/16/00/16/GL 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 This report seeks to advise Committee of the tender process and action taken by the Executive Director of Corporate Services, following consultation with the Convener of the Committee, to appoint Coltart Contracts Ltd to deliver environmental improvements in Coronation Park, New Stevenston. 2. PROPOSAL 2.1 The contract relates to Coronation Park, New Stevenston, a formal park surrounded by residential, commercial and community premises and the adjacent War Memorial on Coronation Road. Perimeter fencing and pathways will be upgraded. Lighting will be provided and access through the community centre re-orientated to improve parking provision. These works will improve the appearance of the park and additional lighting should encourage usage of the park for leisure and as a pedestrian route, making the area safer and discouraging anti social uses. 3 CONSI DE RAT10 N S Contractor Tender Amount Tender Before Checking Amount After Checking Ashlea Landscapes Ltd No offer Coltart Contracts Ltd f287,466.37 f287,518.88 Land Engineering f322,637.49 f321,849.99 AEL Enterprises Ltd f317,102.48 f317,102.48 North Lanarkshire Council Community Services No offer 3.2 The lowest tender of f287,518.88 submitted by Coltart Contracts Limited, was substantially higher than the estimate of f228,OOO reported to the Motherwell Area Committee. Under the provisions of the Contract Standing Orders authority was given to prepare a revised Bill of Quantities and negotiate with the lowest tendering company. -

Local Landscape Character Assessment Background Report

NORTH LANARKSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN LOCAL LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 North Lanarkshire Council Enterprise and Communities CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 3. Kilsyth Hills Special Landscape Area (SLA) 4. Clyde Valley Special Landscape Area (SLA) Appendices Appendix 1 - URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 1. Introduction 1.1 Landscape designations play an important role in Scottish Planning Policy by protecting and enhancing areas of particular value. Scottish Planning Policy encourages local, non-statutory designations to protect and create an understanding of the role of locally important landscape have on communities. 1.2 In 2014, as part of the preparation of the North Lanarkshire Local Development Proposed Plan, a review of local landscape designations was undertaken by URS as part of wider action for landscape protection and management. 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 2.1 The purpose of the Review was to identify and provide an awareness of the special character and qualities of the designated landscape in North Lanarkshire and to contribute to guiding appropriate future development to the most appropriate locations. The Review has identified a number of Local Landscape Units (LLU) that are of notable quality and value within which future development requires careful consideration to avoid potential significant impact on their landscape character. 2.2 There are two exemplar LLUs identified in this study, Kilsyth Hills and Clyde Valley, which are seen as very sensitive to development. Both of these areas warrant specific recognition and protection, as their high landscape quality would be threatened and adversely affected by unsympathetic development within their boundaries. -

Date Registered: Applicant: Agent Development: Location: Ward

Application No: S/04/01037/REM Date Registered: 18th June 2004 Applicant: Transform Schools Office 4 Chryston Business Centre Glasgow G69 9DQ Agent Antoni Rybarczyk Boswell Mitchell & Johnston 18 Woodlands Terrace Glasgow G3 6DH Development: Erection of Joint Campus Primary Schools, Nursery, Public Library and 7-A-Side Floodlit Multi-Purpose Synthetic Pitch for Dual Use with the Community Location: Land At St Patrick’s Primary School And Adjacent Land To Rear Coronation Road East Motherwell Lanarkshire Ward: 5: New Stevenston And Carfin Councillor Helen McKenna Grid Reference: 275953659228 File Reference: SIPLl51351LM Site History: Site occupied by school since before 1948. Outline planning permission granted 21st July 2003 for primary school, nursery, public library and 7-a-side all weather pitch for dual use with the community (App No S/03/00436/0UT) Development Plan: Northern Area Local Plan 1986, Policy HI (Established Housing Area) and Policy El (Green Belt). Southern Area Local Plan Finalised Draft (Modified June 2001) - Policy CS2 (Established Community Facilities) and Policy ENV6 (Green Belt). Contrary to Development Plan: In Part Consultations: Countryside And Landscape Manager (Comments) Director Of Education (No objections) Early Years Section (No objections) S.E. P .A.(West) (Comments) British Gas Transco (Com ments) Scottish Power (Comments) SportScotland (Com ments) Strathclyde Police (No objections) Scottish Natural Heritage (Com ments) Head Of Protective Services (Com ments) Scottish Water (Objections) PLANNING APPLICATION -

AGENDA ITEM No

AGENDA ITEM No. NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To MOTHERWELL & DISTRICT I Subject: JOINT COMMUNITY SAFETY LOCAL AREA PARTNERSHIP REPORT From: HEAD OF PLANNING & REGENERATION Date: 30TH JULY 2014 Ref: JS 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 The purpose of this report is to update members of the Motherwell & District Local Area Partnership on progress with Community Safety in the locality and the joint work carried out in the area by the Local Community Safety Sub−Group over the last period incorporating March − June 2014. 2. Background 2.1 The Joint Community Safety Report reflects the impact which the Local Area Team and Community Safety Sub−groups are making in the area. 3. Proposals/Considerations 3.1 As a result of a review of how community safety is reported to the Local Area Partnerships and the depth and breadth of related statistics that are readily available it was agreed that the statistical analysis normally appended here would be reported every other cycle. There is attached at appendix 1 an up to date copy of the Community Safety Subgroup Action Plan that is regularly updated by partners using the Sharepoint system. 4. Promoting Positive Outcomes 4.1 The community 'ASBO's to tackle street drinking in the centre of the Forgewood area continue to be rigorously enforced and are subject to close monitoring by NLC and CCTV partners. This focus is proving to be successful in eradicating street drinking and is welcomed by the local community and traders in the area. Joint initiatives with Housing Services and Police Scotland and to address youth disorder continues to have a positive effect within the local community and there continues to be a decline in youth offending due to resources being targeted on the main offenders and tenancies where there is a history of offending.