The Takedown of Let's Play and Reaction Videos on Youtube and the Need for Comprehensive DMCA Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of Youtube

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of YouTube Andra Teodora Pacuraru Student Number: 11693436 30/08/2018 Supervisor: Alberto Cossu Second Reader: Bernhard Rieder MA New Media and Digital Culture University of Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 4 Neoliberalism & Personal Branding ............................................................................................ 4 Mass Self-Communication & Identity ......................................................................................... 8 YouTube & Micro-Celebrities .................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 2: Case Studies ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 21 Who They Are ........................................................................................................................... 21 Video Evolution ......................................................................................................................... 22 Audience Statistics ................................................................................................................... -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability

Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research Volume 8 Article 4 2020 The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability Lea Medina Pepperdine University, [email protected] Eric Reed Pepperdine University, [email protected] Cameron Davis Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Medina, Lea; Reed, Eric; and Davis, Cameron (2020) "The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability," Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 21 The 3 P’s: Pewdiepie, Popularity, & Popularity Lea Medina Written for COM 300: Media Research (Dr. Klive Oh) Introduction Channel is an online prole created on the Felix Arvid Ul Kjellberg—more website YouTube where users can upload their aectionately referred to as Pewdiepie—is original video content to the site. e factors statistically the most successful YouTuber, o his channel that will be explored are his with a net worth o over $15 million and over relationships with the viewers, his personality, 100 million subscribers. With a channel that relationship with his wife, and behavioral has uploaded over 4,000 videos, it becomes patterns. natural to uestion how one person can gain Horton and Wohl’s Parasocial such popularity and prot just by sitting in Interaction eory states that interacting front o a camera. -

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

IFA 2020 Crisis Management Paper.Pdf

International Franchise Association Franchise Law Virtual Summit August 12-13, 2020 CRISIS MANAGEMENT IN THE ERA OF FAKE NEWS Bethany Appleby Appleby & Corcoran, LLC New Haven, Connecticut John B. Gessner Fox Rothschild LLP Dallas, Texas Kathryn M. Kotel Smoothie King Franchises, Inc. Dallas, Texas Sarah A. Walters DLA Piper LLP Dallas, Texas WEST\291447123.3 Table of Contents Page I. Introduction and Examples of PR Crises in Recent Years .................................... 1 II. Can Your Company Weather the Storm? ............................................................. 4 A. Development of a Crisis Response Plan.................................................... 6 i. The Crisis Response Team ............................................................. 6 ii. Formulating a Crisis Response Plan ............................................... 7 iii. Crisis Communication Strategies .................................................... 8 iv. Controlling Communications from Franchisees and Personnel ....... 9 v. Crisis Response Training and Mock Crisis Response Trials ......... 10 B. Considerations for Involving Franchisees ................................................ 10 III. When Crisis Happens – Run Into the Flames. .................................................... 11 A. Crisis Management Plan Execution and Parallel Paths to Resolution ..... 11 B. Stabilize Stakeholders – Owners, Franchisees and Customers .............. 13 C. Resolve Central Technical and Operational Challenges .......................... 14 D. Repair the Root -

Sources & Data

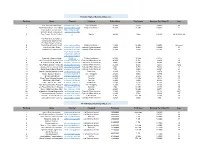

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

The Power of You in Youtube

HA RNESSING THE POWER OF " YOU" IN YouTube How just one word - "YOU" - can double your YouTube viewership Writ t en and Researched by Dane Golden and Phil St arkovich a st udy by and .com HARNESSING THE POWER OF "YOU" IN YOUTUBE - A TUBEBUDDY/ HEY.COM STUDY - Published Feb. 7, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HINT: IT'S NOT ME, IT'S "YOU" various ways during the first 30 platform. But it's more likely that "you" is seconds versus videos that did not say a measurable result of videos that are This study is all about YouTube and "YOU." "you" at all in that period. focused on engaging the audience rather than only talking about the subject of the After extensive research, we've found that saying These findings show a clear advantage videos. YouTube is a personal, social video the word "you" just once in the first 5 seconds of for videos that begin with a phrase platform, and the channels that recognize a YouTube video can increase overall views by such as: "Today I'm going to show you and utilize this factor tend to do better. 66%. And views can increase by 97% - essentially how to improve your XYZ." doubling the viewcount - if "you" is said twice in Importantly, this study shows video the first 5 seconds (see table on page 22). While the word "you" is not a silver creators and businesses how to make bullet to success on YouTube, when more money with YouTube. With the word And "you" affects more than YouTube views. We used in context as a part of otherwise "you," YouTubers can double their also learned that simply saying "you" just once in helpful or interesting videos, combined advertising revenue, ecommerce the first 5 seconds of a video is likely to increase with a channel optimization strategy, companies can drive more website clicks, likes per view by approximately 66%, and overall saying "you" has been proven to apps can drive more downloads, and B2B engagements per view by about 68%. -

Barclays (Pdf, 0.93

Elmar Heggen, CFO London, 3 September 2013 The leading European entertainment network Agenda ● HALF-YEAR HIGHLIGHTS o Strategy Update The leading European entertainment network 2 RTL Group with strong performance in first-half 2013 o Successful IPO at Frankfurt Stock Exchange o Strong interim results demonstrating resilience of diversified portfolio and business model o Significantly higher EBITA and net profit for the first half of 2013 despite tough economic environment o Strong cash flow generation leading to interim dividend payment o Clear focus on executing our growth strategy “broadcast – content – digital” RTL GROUP CONTINUES TO CREATE VALUE The leading European entertainment network 3 Successful IPO € 65,0 RTL Group vs DAX (since April 2013) +13.8% 63,0 61,0 59,0 57,0 +1.1% 55,0 o Largest EMEA IPO this year 53,0 51,0 o Largest media IPO since 2004 29 April 2013 14 May 2013 29 May 2013 13 June 2013 28 June 2013 RTL Group (Frankfurt) DAX (rebased) o SDAX inclusion from 24 June 2013 o Prime standard reporting The leading European entertainment network 4 Half-year highlights 2013 REVENUE €2.8 billion REPORTED EBITA continuing operations €552 million EBITA MARGIN CASH CONVERSION INTERIM DIVIDEND NET RESULT 19.9% 120% €2.5 per share €418 million SECOND BEST FIRST-HALF EBITA RESULT; INTERIM DIVIDEND ANNOUNCED The leading European entertainment network 5 Agenda o Half-year Highlights ● STRATEGY UPDATE The leading European entertainment network 6 Our strategy for success The leading European entertainment network 7 RTL Group continues to lead in all its three strategic pillars Broadcast Content Digital • #1 or #2 in 8 European • #1 global TV entertainment • Leading European media countries content producer company in online video • Leading broadcaster: 56 • Productions in 62 • Strong online sales houses TV and 28 radio channels countries; Distribution into with multi-screen expertise 150+ territories The leading European entertainment network 8 We are working hard on our strategic goals.. -

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................... 1 What Techniques Do Media Manipulators Use? ....... 33 Understanding Media Manipulation ............................ 2 Participatory Culture ........................................... 33 Who is Manipulating the Media? ................................. 4 Networks ............................................................. 34 Internet Trolls ......................................................... 4 Memes ................................................................. 35 Gamergaters .......................................................... 7 Bots ...................................................................... 36 Hate Groups and Ideologues ............................... 9 Strategic Amplification and Framing ................. 38 The Alt-Right ................................................... 9 Why is the Media Vulnerable? .................................... 40 The Manosphere .......................................... 13 Lack of Trust in Media ......................................... 40 Conspiracy Theorists ........................................... 17 Decline of Local News ........................................ 41 Influencers............................................................ 20 The Attention Economy ...................................... 42 Hyper-Partisan News Outlets ............................. 21 What are the Outcomes? .......................................... -

Over 3 Million Youtube Creators Globally Receive Some Level Of

MEDIA FOLLOW THIS Social media entertainment – the kind that has seen huge growth on YouTube and other platforms – needs understanding if there is to be any measured policy response, writes STUART CUNNINGHAM from an Australian perspective ver the past 10 years or so, in the midst of all 1+ million; 2,000+ Australian YouTube channels the cacophony of change we are well familiar earned between $1,000 and $100,000 and more than with, a new creative industry was born. With 100 channels earned more than $100,000. More O my collaborator David Craig, a veteran than 550,000 hours of video were uploaded by Hollywood executive now teaching at the University Australian creators and over 90% of the followers of of Southern California Annenberg School for Australian channels were international. Communication and Journalism, I have been That’s only YouTube, and only the programmatic examining the birth and early childhood of what advertising revenue that can be tracked by Google. we call social media entertainment. It is peopled by A Google-funded study by AlphaBeta2 estimates that cultural leaders, entertainers and activists most of the number of content creators in Australia has whom you may be very unfamiliar with... Here more than doubled over the past 15 years, almost are some of them – Hank Green, Casey Neistat, wholly driven by the entry of 230,000 new creators PewDiePie, Tyler Oakley. of online video content. The same study estimates We understand social media entertainment to be that online video has created a A$6 billion an emerging industry based on previously amateur consumer surplus (the benefit that consumers get creators professionalising and monetising their in excess of what they have paid for that service). -

Youtube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego

From the SelectedWorks of Katrina Wu Spring 2016 YouTube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego Available at: http://works.bepress.com/katrina_wu/2/ YOUTUBE MARKETING: LEGALITY OF SPONSORSHIP AND ENDORSEMENTS IN ADVERTISING Katrina Wua1 Abstract YouTube endorsement marketing, sometimes referred to as native advertising, is a form of marketing where advertisements are seamlessly incorporated into the video content unlike traditional commercials. This paper categorizes YouTube endorsement marketing into three forms: (1) direct sponsorship where the content creator partners with the sponsor to create videos, (2) affiliated links where the content creator gets a commission resulting from purchases attributable to the content creator, and (3) free product sampling where products are sent to content creators for free to be featured in a video. Examples in each of the three forms of YouTube marketing can be observed across virtually all genres of video, such as beauty/fashion, gaming, culinary, and comedy. There are four major stakeholder interests at play—the YouTube content creators, viewers, YouTube, and the companies—and a close examination upon the interplay of these interests supports this paper’s argument that YouTube marketing is trending and effective but urgently needs transparency. The effectiveness of YouTube marketing is demonstrated through a hypothetical example in the paper involving a cosmetics company providing free product sampling for a YouTube content creator. Calculations in the hypothetical example show impressive return on investment for such marketing maneuver. Companies and YouTube content creators are subject to disclosure requirements under Federal law if the content is an endorsement as defined by the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”). -

Retoryka Cyfrowa Digital Rhetoric

ISSN: 2392-3113 Retoryka cyfrowa Digital Rhetoric 4/2016 EDITORS: AGNIESZKA KAMPKA, EWA MODRZEJEWSKA MAGDALENA PIETRUSZKA OPOLE [email protected] Watching people playing games: A survey of presentational techniques in most popular game-vlogs Przegląd technik prezentacyjnych najpopularniejszych vlogów poświęconych grom komputerowym Abstract This study is dedicated to the mechanisms of popularity of YouTube vloggers that upload gaming videos. The presentational techniques used in those videos are examined to identify the reasons of their popularity and the tools used by the gamers to engage the audience. Three popular 2016 YouTube gamers were selected and evaluated according to the ranking of online popularity (PewDiePie, Markiplier, Cryaotic). The study aims to explain the relation between the number of subscribers and the presentational techniques they use to gain popularity. Accordingly, the relations between the vlogger’s uploads and the audience’s response are grasped by analysing the content of the videos in selected channels along with the ways their owners present themselves. Niniejsze studium jest poświęcone fi lmikom na temat gier komputerowych publikowanych na portalu YouTube oraz popularności vlogerów, którzy je nagrywają. Analizie poddano techniki prezentacyjne wykorzystywane przez vlogerów w celu przyciągnięcia uwagi odbiorców. Wybrano i oceniono trzech popularnych twórców (PewDiePie, Markiplier, Cryaotic), sugerując się internetowym rankingiem popularności. Przeanalizowano zależność pomiędzy liczbą subskrybentów a technikami prezentacyjnymi używanymi przez vlogerów. W ten sposób ustalono relacje między popularnością udostępnianych fi lmów o grach z wybranych kanałów na YouTube a treścią tychże fi lmów oraz sztuką prezentacji stosowaną przez ich twórców. Key words vlogging, YouTube, gaming business, presentational techniques vlogi, YouTube, rynek gier komputerowych, techniki prezentacyjne License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Poland.