IFA 2020 Crisis Management Paper.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report | Review of John Schnatter Statements and Media Response

Final Report | Review of John Schnatter Statements and Media Response For Release: December 7, 2020 Freeh Group International Solutions, LLC Attorney Client Privilege Attorney Work Product Privileged and Confidential Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 2 Comments on the NFL .............................................................................................................................. 3 Comments on the Diversity Training Call ................................................................................................ 6 FGIS Interview Findings ........................................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 12 P a g e | 1 Attorney Client Privilege Attorney Work Product Privileged and Confidential Introduction Freeh Group International Solutions, LLC (“FGIS”) at the direction of the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP was engaged to: (1) conduct an assessment of public statements by Mr. John Schnatter relating to race in order to assess the disparity between his statements and press reports concerning such statements; (2) interview -

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

1998 Annual Report

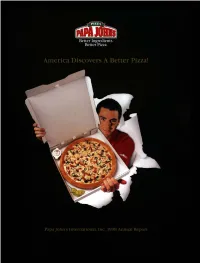

To Our Shareholders, Team Members and Franchisees In 1985, when I was serving pizza out of a effect of a change in accounting for pre-opening broom closet in my dad’s tavern, one thought costs). We ended the year with the strongest kept me going: I believed I could make a better balance sheet in our history, including stock- pizza than the big chains. The problem was, in holder’s equity of $262.7 million (with only 1985 I was the only person who believed that. $1.3 million in long-term debt) and more than Not anymore. Fourteen years later, America $81 million in cash and investments to fuel our has discovered a better pizza! continued growth. For the third consecutive year, consumers Our passion for quality and increasing market have awarded Papa John’s top honors among share generated a great deal of interest in the national delivery pizza chains in the prestigious national media last year. Papa John’s was Restaurants and Institutions’ Choice in Chains featured in Time, Fortune, The New York Times, survey. With nearly 2,000 restaurants throughout The Los Angeles Times, The Dallas Morning News the U.S. and in four international markets, more and Investor’s Business Daily, among others. and more people every day are discovering why Also during 1998: better ingredients really do make a better pizza. ■ Nearly 10% of restaurants in our system Once again, our operating results were out- at the beginning of 1998 averaged more standing. In 1998 we surpassed $1 billion in than $1 million in annual sales. -

Youtube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego

From the SelectedWorks of Katrina Wu Spring 2016 YouTube Marketing: Legality of Sponsorship and Endorsement in Advertising Katrina Wu, University of San Diego Available at: http://works.bepress.com/katrina_wu/2/ YOUTUBE MARKETING: LEGALITY OF SPONSORSHIP AND ENDORSEMENTS IN ADVERTISING Katrina Wua1 Abstract YouTube endorsement marketing, sometimes referred to as native advertising, is a form of marketing where advertisements are seamlessly incorporated into the video content unlike traditional commercials. This paper categorizes YouTube endorsement marketing into three forms: (1) direct sponsorship where the content creator partners with the sponsor to create videos, (2) affiliated links where the content creator gets a commission resulting from purchases attributable to the content creator, and (3) free product sampling where products are sent to content creators for free to be featured in a video. Examples in each of the three forms of YouTube marketing can be observed across virtually all genres of video, such as beauty/fashion, gaming, culinary, and comedy. There are four major stakeholder interests at play—the YouTube content creators, viewers, YouTube, and the companies—and a close examination upon the interplay of these interests supports this paper’s argument that YouTube marketing is trending and effective but urgently needs transparency. The effectiveness of YouTube marketing is demonstrated through a hypothetical example in the paper involving a cosmetics company providing free product sampling for a YouTube content creator. Calculations in the hypothetical example show impressive return on investment for such marketing maneuver. Companies and YouTube content creators are subject to disclosure requirements under Federal law if the content is an endorsement as defined by the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”). -

Business Woman

ISSUE 3 FEMALES IN FRANCHISING “Women are brilliant at 100 starting up” INFLUENTIAL WOMEN INTERVIEW: EMMA JONES, IN FRANCHISING CEO, ENTERPRISE NATION Meet the class of 2020 Entrepreneur’s handbook: ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO FRANCHISING Introducing the hottest lifestyle franchise of the year Seasons Art Class is pandemic-proof, fun, profitable and From the publisher of rewarding in every way What Franchise Global Plus: The rise of ‘Zutors’ • 3 big reasons small Franchise businesses fail • Start-up tips from female founders BUSINESS WOMAN ISSUE 3 master_GLOBAL FRANCHISE 08/10/2020 13:42 Page 2 BUSINESS WOMAN ISSUE 3 master_GLOBAL FRANCHISE 08/10/2020 13:42 Page 3 BUSINESS WOMAN ISSUE 3 master_GLOBAL FRANCHISE 09/10/2020 07:52 Page 4 Contents COVER STORIES 26 COVID-19’S IMPACT ON EDUCATION 30 EMMA JONES, From the rise of ‘Zutors’ to pandemic ENTERPRISE NATION pods, the pandemic has changed the The organisation’s founder talks about way we deliver education to children the current business environment 32 MARTHA MATILDA HARPER and what the future holds for small Get to know the Canadian house business owners servant who pioneered international 46 100 INFLUENTIAL WOMEN franchising back in 1891 IN FRANCHISING INTERVIEWS Meet the class of 2020 15 74 THE SEASONS ART CLASS 38 TAKE THE LEAP How Kimberlee Perry turned £200 into a The perfect part-time business, 83 PROMOTE HEALTH leading, international, trampolining brand where you can work from home and AND WELLBEING generate a full-time income 40 HOW TO BUILD A Want to get into the fitness NATIONAL BRAND -

Pizza Power Using Only the Best Ingredients for 30 Years, Papa John’S Is Embracing High- Profile Branding Opportunities Leveraging the Newest Technology

RETAIL >r Papa John’s Pizza Power Using only the best ingredients for 30 years, Papa John’s is embracing high- profile branding opportunities leveraging the newest technology. By Jeff Borgardt company profile Papa John’s www.papajohns.com Annual revenue: $1.34 billion HQ: Louisville, Ky. Employees: 100,000 Specialty: Pizza delivery/ takeout, franchising Tony Thompson, president and COO: “The focus on quality has been consistent throughout our 30 years’ history. We are almost religious about it. We don’t com - promise on our brand standards.” or Papa John’s, it’s all about the quality. Offering fresh and tasty ingredients distinguishes it from others in a crowded pizza market, Fthe company says. “We have better ingredients, better pizza. That really is what we are all about,” says Tony Thompson, president and COO. Papa John’s slogan, “Better Ingredients. Better Pizza.” describes its “all-natural sauce, freshly cut vegeta - bles and premium meats and cheeses,” the company says. Dough, cheese and toppings Papa John’s success begins with its ingredients. Papa John’s pizza is pre - pared using fresh, unfrozen dough, which is placed in store coolers long enough for it to proof and rise. Once ready, it is hand-tossed. The proprietary dough does not use “dough-conditioners” such as sodium stearoyl lactylate or mono- and diglyc - erides. The high-protein dough made with unbleached wheat flour and fil - tered water gives the pizza dough its balance of flavor and chewy crust. The << Founder John Schnatter gave away free pizzas to anyone who owned a Camaro when he was reunited with this own. -

But Its Just a Game Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BUT ITS JUST A GAME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julia Cook,Michelle Hazelwood Hyde | 30 pages | 05 Sep 2013 | National Center for Youth Issues | 9781937870164 | English | Chattanooga, United States But Its Just a Game PDF Book You are ok with what happened, losing, imperfection of a craft. After this, PewDiePie watched a clip of Ninja echoing the sentiments of the tweet, laughing through the video and the memes poking fun at the take. Nov 15, 3. And they aim for console gamers, usually teenies, not intested in history but on tiddies and winning easy wars not all teenies of course. I don't mean this as a slight on the workers actually developing the games, they are clearly passionate about them and I'm sure would gladly have more resources available were it up to them. That was a 2-for-1 deal; they were going to come to Autzen twice; we were going to back to Hawaii once. But, while running the App troubleshooter, it said "Display Adapter Drivers might be out of date". But I checked for Display adapter update and found that I have the latest one installed. Read exclusive stories only found here. This site in other languages x. Subscribe to OregonLive. Of course, come next week, everyone will forget this even happened, but there's no doubting it was the biggest moment in gaming this week, which explains why PewDiePie had to react to it. Advisors may now jockey for positions of influence and adversaries should save their schemes for another day, because on this day Crusader Kings III can be purchased on Steam, the Paradox Store, and other major online retailers. -

University of Miami Examining Transparency in Crisis

Please do not remove this page Examining Transparency in Crisis Management Buon Viso, Tessa https://scholarship.miami.edu/discovery/delivery/01UOML_INST:ResearchRepository/12355268700002976?l#13355497920002976 Buon Viso, T. (2013). Examining Transparency in Crisis Management [University of Miami]. https://scholarship.miami.edu/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991031447232202976/01UOML_INST:ResearchR epository Open Downloaded On 2021/09/30 21:07:23 -0400 Please do not remove this page UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI EXAMINING TRANSPARENCY IN CRISIS MANAGEMENT By Tessa Buon Viso A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Coral Gables, Florida May 2013 ©2013 Tessa Buon Viso All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts EXAMINING TRANSPARENCY IN CRISIS MANAGEMENT Tessa Buon Viso Approved: ________________ _________________ Don W. Stacks, Ph.D. M. Brian Blake, Ph.D. Professor of Public Relations Dean of the Graduate School ________________ Shannon B. Campbell, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Public Relations ________________ Walter McDowell, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Electronic Media, Broadcast Journalism and Media Management BUON VISO, TESSA (M.A., Public Relations) Examining Transparency in Crisis Management (May 2013) Abstract of a thesis at the University of Miami. Thesis supervised by Professor Don Stacks. No. of pages in text: (65) . Considered a benefit to the building of reputation by Public Relations professionals, transparency is increasingly viewed as an intangible asset for corporations to assimilate into their business. This thesis divides transparency into two separate categories, informal and formal transparency, and examines the role both play in creating and solving crises. -

Papa John's Launches "Pizza Family" Campaign Week of Super Bowl LI

February 2, 2017 Papa John's Launches "Pizza Family" Campaign Week of Super Bowl LI Papa John's unveils new logo featuring Team Members, pizza box, and TV spots to support new brand campaign LOUISVILLE, Ky.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The Official Pizza Sponsor of the NFL and Super Bowl LI, Papa John's International, Inc. (NASDAQ:PZZA), is launching a new brand campaign, "WE'RE MORE THAN A PIZZA COMPANY, WE'RE A PIZZA FAMILY," the week of Super Bowl LI (51), inviting Team Members, sports fans and pizza lovers around the world to further engage with the brand and learn about its history. An evolution of the BETTER INGREDIENTS. BETTER PIZZA. promise, Papa John's Pizza Family campaign highlights one of its most important ingredients - its people. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170202005428/en/ "Super Bowl Sunday is our number one sales and delivery day, so it seemed fitting to unveil our new ‘Pizza Family' brand campaign ahead of our biggest day of the year," said "Papa" John Schnatter, Founder, Chairman, and CEO of Papa John's International. "With the recent opening of our 5,000th store location, it's the right moment to reflect on our success and to celebrate those who have made it happen - from our pizza makers and delivery drivers to our trusted ingredient suppliers and our loyal customers around the world - this is the Pizza Family that makes it all possible." Onsite Super Bowl LI Activations Papa John's is kicking off the Pizza Family campaign in Houston at Super Bowl LI by bringing to life the brand's inspiring story of one man's dream to make a better pizza. -

SEC News Cover.Qxp

CoSIDA NEWS Intercollegiate Athletics News from Around the Nation May 7, 2007 Paying coaches big dollars just makes sense for colleges Page 1 of 2 http://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/college/bal-sp.whitley29apr29,0,7964613.story?coll=bal-college-sports From the Baltimore Sun Paying coaches big dollars just makes sense for colleges April 29, 2007 The year's most astounding sports number came out of Tuscaloosa last weekend: 92,138. That's how many fans showed up at Alabama's spring football game. I don't know whether to laugh, cry or invest in Nick Saban's new clothing line. I do know it should answer the concerns of people who think certain university employees are wildly overpaid. "You have to ask the hard questions," NCAA president Myles Brand said. "Is it the appropriate thing to do within the context of college sports?" He was responding to a question about the gold mine Kentucky was ready to dig for Florida basketball coach Billy Donovan. That came after Saban got his $4-million-a-year windfall. And in this week's affront to academic integrity, Rutgers announced its women's basketball coach is going to be making as much as its football coach. It will be interesting to see whether there's the same outcry when a woman cashes in, but that's beside the point. The point is that if anyone still is looking at this in the context of college sports, they hopelessly are blind to reality. The reality is that college sports is an increasingly gargantuan business. -

NBCU Pulls out All the Stops to Promote Summer Shows

NBCU Pulls Out All the Stops to Promote Summer Shows 04.02.2015 With an emphasis on content, no matter what the calendar reads, the summer season of TV has become more and more important for networks, always looking to make a splash. On Thursday, April 2, at The Langham Huntington Hotel and Spa in Pasadena, NBCUniversal provides the media its first glimpse into some of their new and returning summer and fall properties hoping to make its mark in 2015. Welcome to NBCUniversal's Summer Press Day, an event featuring a series of panels with stars and executives in attendance to promote and introduce their respective shows. After snagging a Sharknado coozie and a breakfast burrito filled catered breakfast, the panels begin in the Ballroom with our first show… Just what everyone needs to start their summer right. America's Got Talent (NBC) In Attendance: Executive Producers Jason Raff and Sam Donnelly; Judges Howie Mandel, Mel B and Heidi Klum; Host Nick Cannon The hit reality competition show is celebrating its 10th anniversary season, as evidenced by its new hashtag #AGT10. The mood was celebratory from the start, with Howie Mandel kicking off the panel with a mimosa toast (at 9 AM - never too early) to the press and everyone involved with the show. "To another 10 years," Mandel says as he raises a glass to what he describes as a bigger, better and different show. One that includes more laughs for Heidi Klum, who teased that this summer's rendition will feature more comedians who are actually funny.