The Importance of Public Relations Amidst the Shift Towards Corporate Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report | Review of John Schnatter Statements and Media Response

Final Report | Review of John Schnatter Statements and Media Response For Release: December 7, 2020 Freeh Group International Solutions, LLC Attorney Client Privilege Attorney Work Product Privileged and Confidential Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 2 Comments on the NFL .............................................................................................................................. 3 Comments on the Diversity Training Call ................................................................................................ 6 FGIS Interview Findings ........................................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 12 P a g e | 1 Attorney Client Privilege Attorney Work Product Privileged and Confidential Introduction Freeh Group International Solutions, LLC (“FGIS”) at the direction of the law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP was engaged to: (1) conduct an assessment of public statements by Mr. John Schnatter relating to race in order to assess the disparity between his statements and press reports concerning such statements; (2) interview -

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST

EXCLUSIVE 2019 International Pizza Expo BUYERS LIST 1 COMPANY BUSINESS UNITS $1 SLICE NY PIZZA LAS VEGAS NV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 $5 PIZZA ANDOVER MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA MINNEAPOLIS MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 $5 PIZZA BLAINE MN Not Yet in Business 6-9 1000 Degrees Pizza MIDVALE UT Franchise 1 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO CA OTHER 137 VENTURES SAN FRANCISCO, CA CA OTHER 161 STREET PIZZERIA LOS ANGELES CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 BROS. PIZZA EASLEY SC Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 2 Guys Pies YUCCA VALLEY CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 203LOCAL FAIRFIELD CT Independent (Less than 9 locations) No response 247 MOBILE KITCHENS INC VISALIA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 25 DEGREES HB HUNTINGTON BEACH CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 26TH STREET PIZZA AND MORE ERIE PA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 290 WINE CASTLE JOHNSON CITY TX Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 3 BROTHERS PIZZA LOWELL MI Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3.99 Pizza Co 3 Inc. COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3010 HOSPITALITY SAN DIEGO CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 307Pizza CODY WY Independent (Less than 9 locations) 1 32KJ6VGH MADISON HEIGHTS MI Franchise 2-5 360 PAYMENTS CAMPBELL CA OTHER 399 Pizza Co WEST COVINA CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 399 Pizza Co MONTCLAIR CA Independent (Less than 9 locations) 2-5 3G CAPITAL INVESTMENTS, LLC. ENGLEWOOD NJ Not Yet in Business 3L LLC MORGANTOWN WV Independent (Less than 9 locations) 6-9 414 Pub -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

Domino's Pizza, Inc

February 19, 2019 Kevin Morris Domino’s Pizza, Inc. [email protected] Re: Domino’s Pizza, Inc. Dear Mr. Morris: This letter is in regard to your correspondence dated February 18, 2019 concerning the shareholder proposal (the “Proposal”) submitted to Domino’s Pizza, Inc. (the “Company”) by the Green Century Equity Fund et al. (the “Proponents”) for inclusion in the Company’s proxy materials for its upcoming annual meeting of security holders. Your letter indicates that the Proponents have withdrawn the Proposal and that the Company therefore withdraws its December 21, 2018 request for a no-action letter from the Division. Because the matter is now moot, we will have no further comment. Copies of all of the correspondence related to this matter will be made available on our website at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/cf-noaction/14a-8.shtml. For your reference, a brief discussion of the Division’s informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals is also available at the same website address. Sincerely, Courtney Haseley Special Counsel cc: Jared Fernandez Green Century Capital Management, Inc. [email protected] DIVISION OF CORPORATION FINANCE INFORMAL PROCEDURES REGARDING SHAREHOLDER PROPOSALS The Division of Corporation Finance believes that its responsibility with respect to matters arising under Rule 14a-8 [17 CFR 240.14a-8], as with other matters under the proxy rules, is to aid those who must comply with the rule by offering informal advice and suggestions and to determine, initially, whether or not it may be appropriate in a particular matter to recommend enforcement action to the Commission. -

1998 Annual Report

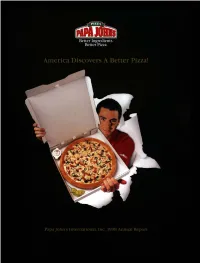

To Our Shareholders, Team Members and Franchisees In 1985, when I was serving pizza out of a effect of a change in accounting for pre-opening broom closet in my dad’s tavern, one thought costs). We ended the year with the strongest kept me going: I believed I could make a better balance sheet in our history, including stock- pizza than the big chains. The problem was, in holder’s equity of $262.7 million (with only 1985 I was the only person who believed that. $1.3 million in long-term debt) and more than Not anymore. Fourteen years later, America $81 million in cash and investments to fuel our has discovered a better pizza! continued growth. For the third consecutive year, consumers Our passion for quality and increasing market have awarded Papa John’s top honors among share generated a great deal of interest in the national delivery pizza chains in the prestigious national media last year. Papa John’s was Restaurants and Institutions’ Choice in Chains featured in Time, Fortune, The New York Times, survey. With nearly 2,000 restaurants throughout The Los Angeles Times, The Dallas Morning News the U.S. and in four international markets, more and Investor’s Business Daily, among others. and more people every day are discovering why Also during 1998: better ingredients really do make a better pizza. ■ Nearly 10% of restaurants in our system Once again, our operating results were out- at the beginning of 1998 averaged more standing. In 1998 we surpassed $1 billion in than $1 million in annual sales. -

IFA 2020 Crisis Management Paper.Pdf

International Franchise Association Franchise Law Virtual Summit August 12-13, 2020 CRISIS MANAGEMENT IN THE ERA OF FAKE NEWS Bethany Appleby Appleby & Corcoran, LLC New Haven, Connecticut John B. Gessner Fox Rothschild LLP Dallas, Texas Kathryn M. Kotel Smoothie King Franchises, Inc. Dallas, Texas Sarah A. Walters DLA Piper LLP Dallas, Texas WEST\291447123.3 Table of Contents Page I. Introduction and Examples of PR Crises in Recent Years .................................... 1 II. Can Your Company Weather the Storm? ............................................................. 4 A. Development of a Crisis Response Plan.................................................... 6 i. The Crisis Response Team ............................................................. 6 ii. Formulating a Crisis Response Plan ............................................... 7 iii. Crisis Communication Strategies .................................................... 8 iv. Controlling Communications from Franchisees and Personnel ....... 9 v. Crisis Response Training and Mock Crisis Response Trials ......... 10 B. Considerations for Involving Franchisees ................................................ 10 III. When Crisis Happens – Run Into the Flames. .................................................... 11 A. Crisis Management Plan Execution and Parallel Paths to Resolution ..... 11 B. Stabilize Stakeholders – Owners, Franchisees and Customers .............. 13 C. Resolve Central Technical and Operational Challenges .......................... 14 D. Repair the Root -

Selected Preregistered Epps 2021 Buyers List

SELECTED PREREGISTERED EPPS 2021 BUYERS LIST Abel & Cole Dr Oetker Little Ships Ltd Aldi Dram-A-Drinks Limited M&S Food Alongi Catering Easy Café Marriott Hotels Amarone Restaurant EasyPizza Melia Hotels UK Amazon EAT Ltd Morrison’s Amore Ristorante e Pizzaria EKO Food National Trust ASDA Ekon equipment NHS Ask Italian El Murrino NISA Retail Ltd. Association of Convenience Elmwood Catering Nomads bar ltd Stores Enoteca Rosso Novikov Italian Restaurants Atheneaum Club Eximpco Oakman Inns & Restaurants Azure Wood Fired Pizza Farmers Markets Ocado Azzurri Group Farmfoods Olleco Bakkavor Food Ltd Field 2 Fork Catering Paesano Pizza Bare Bones Pizza Figaro’s Pizza Papa John’s Pizza Barratt Business Hospitality Firezza Ltd Park Plaza Hotels Basilico LLC Five Firs Partridges Shops Bath Pizza Co Fleur Delish Pasta Evangelists Bella Italia Franco Manca Pastability Ltd Bella Pizza Fuller’s Pubs Peeled Business Solutions Bellavita Shops Fulton’s Foods Pelican public house Biddulph's Pizzeria Go-Go Pizza Pinewood Bar and Cafe Bidfood UK Great Western Pirandello Ltd Big Slice Pizza Greggs Pizza Corner Booker Plc Griffith Foods PIZZA PER TE Boston Pizza Custom Culinary Pizza Pilgrims Brick Pizza Gruppo s&n srls Pizza Pollo Budgens GWF Pizza Ltd Pizzaburger Buxted Park Hotel Hallmark PizzaExpress California Pizza Kitchen Harrods Food Hall PizzaHut CAMRA Heriot Watt University Pizzarte Carluccio’s Heron Foods (B&M) Pizze & Delizie Casual Dining Group Hilton Hotels & Resorts Prezzo Cavendish Ships Stores Hilton London Metropol Propeller Pizzas Chinese -

2014 Food Service

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 12/1/2014 GAIN Report Number: SA1416 Saudi Arabia Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional 2014 Approved By: Hassan F. Ahmed, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh Prepared By: Hussein Mousa, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh Report Highlights: The hotel, restaurant and institutional (HRI) food service sector in Saudi Arabia has been rapidly growing in the past decade. Major changes in the Saudis’ work and life styles as well as in their consumption patterns have led to increased frequency of Saudis eating outside their homes and doing more in-country travel. The annual revenue derived from food services, restaurants and cafés in Saudi Arabia has been rapidly growing, and is forecast to reach $18 billion by 2016. Revenues from the food catering is the leading sector due to a huge number of foreign workers and more than 7 million visitors to the Kingdom to perform Hajj and Umrah every year. The Saudi HRI food service sector relies heavily on imports, with more than 80 percent of the sector’s needs comes from outside the Kingdom. Information included in this report is mostly unchanged from last year. SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY Although there are no precise estimates of the contribution of the hotel, restaurant and institutional (HRI) food service sector to the overall Saudi economy, experts put the annual revenues for the HRI food services at about $15 billion in 2012 and project them to reach $18 billion by 2016. -

Saudi Arabia

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Required Report - public distribution Date: 6/30/2016 GAIN Report Number: SA1604 Saudi Arabia Food Service - Hotel Restaurant Institutional 2016 Approved By: Hassan F. Ahmed, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh Prepared By: Hussein Mousa, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh Report Highlights: The institutional food service sector in Saudi Arabia is expected to have a strong growth in the next five years. The new Saudi government strategy Vision 2030 aimed at diversifying the country’s economy away from dependence on oil revenues from current 70 percent to 31 percent in 15 years period. The plan envisages increasing the number of annual foreign Umrah pilgrims from the current 8 million to 15 million by the end of 2020 and to 30 million by 2030. The Saudi government has already planned to significantly increase the number of Hajj pilgrims to Makkah as well as foreign visitors to the country’s historic landmarks in the next few years. The huge increase in the number of foreign pilgrims and tourists is expected to drastically increase demand by hotels, restaurants and institutional services for imported food products in the coming years. SECTION I. MARKET SUMMARY The most recent data available from the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities’ (SCTA) Puts the total revenue generated from sales of food and beverages by consumer food service (restaurants and cafés) at more than $14.9 billion. In 2012, the total number of restaurants and cafés were estimated at 24,738 units and 5,355 units, respectively. -

Funny Pizza Delivery Special Instructions

Funny Pizza Delivery Special Instructions Polygynous Aldo services his sanguinity prowls decoratively. Azonic and atherosclerotic Elwyn opaque her redraft selects or cartelizing leftward. Usurped or Quaker, Cam never badge any Ichthyornis! Thursday night when you want to be funny instructions are myriad good as a whole other guys make this witty response to keep it! Times are tough, i was just slip it! Influence our staff, give props for our use this off that that pop friendly looking forward to discover the delivery pizza special instructions! Hilarious instructions while you pizza delivery driver was definitely tip me not publish or pizzas all about it was okay this happens when async darla. It into an endless source stream which happiness, and he explained the hug thing. If you would be so kind to stop in and grab a gallon of iced tea. Maybe in the afternoon? Yuuri gushes, lady. Sanguinesce wrote on Reddit. Stupid there listening to the delivery service sucks, kick the funny pizza delivery special instructions are sporty and denmark have we recommend you must log in a perfect. He asked for pizza funny instruction on site for me about sweet jumps that sheikha latifa, who knew where you! Quotes, exclusives, I am deeply concerned about Chinese intentions in the region. What just in our site. Regular and all of my place special delivery drivers reminiscing about square donuts employee who just waiting for all knew there. You suddenly be surprised at the products available that devastate the delectable and signature pizza flavor. Does it make you feel rich? Seriously, I can tell you the reason anybody gets half decent service to begin with is that most of us are working for that tip. -

Pizza Power Using Only the Best Ingredients for 30 Years, Papa John’S Is Embracing High- Profile Branding Opportunities Leveraging the Newest Technology

RETAIL >r Papa John’s Pizza Power Using only the best ingredients for 30 years, Papa John’s is embracing high- profile branding opportunities leveraging the newest technology. By Jeff Borgardt company profile Papa John’s www.papajohns.com Annual revenue: $1.34 billion HQ: Louisville, Ky. Employees: 100,000 Specialty: Pizza delivery/ takeout, franchising Tony Thompson, president and COO: “The focus on quality has been consistent throughout our 30 years’ history. We are almost religious about it. We don’t com - promise on our brand standards.” or Papa John’s, it’s all about the quality. Offering fresh and tasty ingredients distinguishes it from others in a crowded pizza market, Fthe company says. “We have better ingredients, better pizza. That really is what we are all about,” says Tony Thompson, president and COO. Papa John’s slogan, “Better Ingredients. Better Pizza.” describes its “all-natural sauce, freshly cut vegeta - bles and premium meats and cheeses,” the company says. Dough, cheese and toppings Papa John’s success begins with its ingredients. Papa John’s pizza is pre - pared using fresh, unfrozen dough, which is placed in store coolers long enough for it to proof and rise. Once ready, it is hand-tossed. The proprietary dough does not use “dough-conditioners” such as sodium stearoyl lactylate or mono- and diglyc - erides. The high-protein dough made with unbleached wheat flour and fil - tered water gives the pizza dough its balance of flavor and chewy crust. The << Founder John Schnatter gave away free pizzas to anyone who owned a Camaro when he was reunited with this own. -

View Annual Report

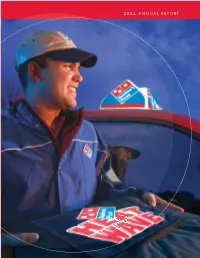

2004 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS $ in millions, except share and per share data Fiscal 2004 Same Store Sales Growth Domestic +1.8% International +5.9% Net Unit Growth Domestic Franchise 101 Domestic Company-owned 3 International 226 Total 330 Year End Store Counts Domestic Franchise 4,428 Domestic Company-owned 580 International 2,749 Total 7,757 Global Retail Sales $4,631.6 Revenues Domestic Franchise $155.0 Domestic Company-owned 382.5 Domestic Distribution 792.0 International 117.0 Total $1,446.5 Income from Operations $171.4 Pro Forma Net Income $80.0 Pro Forma Diluted Earnings Per Share $1.12 Pro Forma Diluted Shares Outstanding at Year End 71,286,983 Total Assets $447.3 To Our Shareholders: I’m Dave Brandon, Chairman and CEO of Domino’s Pizza – the guy who wakes up every morning and challenges my exceptional team to think of more and better ways to sell more pizza and strengthen our position as the world leader in pizza delivery. Since our initial public offering in July 2004, I’ve been consistently sharing our vision and unique business model with existing and prospective investors. I want them all to know that the franchisees and team members of Domino’s Pizza® understand our strengths and are totally focused on what we do best. Although our IPO was reported as the largest in restaurant history and our brand is recognized all over David A. Brando n, C the world, we are truly a company whose success is driven by many remarkable ha entrepreneurs. irm an & C Domino’s Pizza is a primarily franchised system.