How's It Going Bros: Pewdiepie's Memeing in Tertiary Orality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of Youtube

Identity and Representation on the Neoliberal Platform of YouTube Andra Teodora Pacuraru Student Number: 11693436 30/08/2018 Supervisor: Alberto Cossu Second Reader: Bernhard Rieder MA New Media and Digital Culture University of Amsterdam Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................................ 4 Neoliberalism & Personal Branding ............................................................................................ 4 Mass Self-Communication & Identity ......................................................................................... 8 YouTube & Micro-Celebrities .................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 2: Case Studies ........................................................................................................................ 21 Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 21 Who They Are ........................................................................................................................... 21 Video Evolution ......................................................................................................................... 22 Audience Statistics ................................................................................................................... -

Audio-Visual Genres and Polymediation in Successful Spanish Youtubers †,‡

future internet Article Audio-Visual Genres and Polymediation in Successful Spanish YouTubers †,‡ Lorenzo J. Torres Hortelano Department of Sciences of Communication, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, 28943 Fuenlabrada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected]; Tel.: +34-914888445 † This paper is dedicated to our colleague in INFOCENT, Javier López Villanueva, who died on 31 December 2018 during the finalization of this article, RIP. ‡ A short version of this article was presented as “Populism, Media, Politics, and Immigration in a Globalized World”, in Proceedings of the 13th Global Communication Association Conference Rey Juan Carlos University, Madrid, Spain, 17–19 May 2018. Received: 8 January 2019; Accepted: 2 February 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: This paper is part of broader research entitled “Analysis of the YouTuber Phenomenon in Spain: An Exploration to Identify the Vectors of Change in the Audio-Visual Market”. My main objective was to determine the predominant audio-visual genres among the 10 most influential Spanish YouTubers in 2018. Using a quantitative extrapolation method, I extracted these data from SocialBlade, an independent website, whose main objective is to track YouTube statistics. Other secondary objectives in this research were to analyze: (1) Gender visualization, (2) the originality of these YouTube audio-visual genres with respect to others, and (3) to answer the question as to whether YouTube channels form a new audio-visual genre. I quantitatively analyzed these data to determine how these genres are influenced by the presence of polymediation as an integrated communicative environment working in relational terms with other media. My conclusion is that we can talk about a new audio-visual genre. -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

'Tommy Wiseau's '

MEDIA ALERT – January 16, 2018 Due to Overwhelming Fan Demand, Encore of ‘Tommy Wiseau’s ‘The Room’’ Comes to Cinemas for One More Night on January 19 WHAT: Referred to as "the ‘Citizen Kane’ of bad movies," “The Room” has received a remarkable resurgence due to the popularity of James Franco’s “The Disaster Artist” and Tommy Wiseau’s recent appearance on The Golden Globes. On January 10, fans came out in droves as Wiseau’s opus hit more than 500 big screens across the nation with “Tommy Wiseau’s ‘The Room.’” Due to overwhelming demand, an encore screening has been set for Friday, January 19, 2018. In addition to the full-length feature, moviegoers will enjoy a special look at the new “Best F(r)iends” trailer, starring Wiseau and Greg Sestero. Starring Tommy Wiseau, directed by Tommy Wiseau, written by Tommy Wiseau, screenplay by Tommy Wiseau and produced by Tommy Wiseau, “The Room” follows the story of Johnny (Wiseau). Johnny is a bank employee who, seemingly, lives happily in a San Francisco townhouse with Lisa, his fiancée. One day she gets bored with Tommy and seduces his best friend, Mark (played by Wiseau’s best friend, Greg Sestero, author of the award-winning 2013 memoir “The Disaster Artist”). Johnny screams, “You’re tearing me apart, Lisa!”– and, with that, nothing, or no one, will ever be the same. WHO: Fathom Events WHEN: Friday, January 19, 2018; 7:00 p.m. local time WHERE: Tickets for “Tommy Wiseau’s ‘The Room’” encore will be available throughout the week online by visiting www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. -

Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability

Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research Volume 8 Article 4 2020 The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability Lea Medina Pepperdine University, [email protected] Eric Reed Pepperdine University, [email protected] Cameron Davis Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Medina, Lea; Reed, Eric; and Davis, Cameron (2020) "The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability," Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 21 The 3 P’s: Pewdiepie, Popularity, & Popularity Lea Medina Written for COM 300: Media Research (Dr. Klive Oh) Introduction Channel is an online prole created on the Felix Arvid Ul Kjellberg—more website YouTube where users can upload their aectionately referred to as Pewdiepie—is original video content to the site. e factors statistically the most successful YouTuber, o his channel that will be explored are his with a net worth o over $15 million and over relationships with the viewers, his personality, 100 million subscribers. With a channel that relationship with his wife, and behavioral has uploaded over 4,000 videos, it becomes patterns. natural to uestion how one person can gain Horton and Wohl’s Parasocial such popularity and prot just by sitting in Interaction eory states that interacting front o a camera. -

The 2Nd International Conference on Internet Pragmatics - Netpra2

THE 2ND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INTERNET PRAGMATICS - NETPRA2 INTERACTIONS, IDENTITIES, INTENTIONS 22–24 October 2020 BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Table of Contents Keynotes ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Anita Fetzer (University of Augsburg) ................................................................................................. 6 “It’s a very good thing to bring democracy erm directly to everybody at home”: Participation and discursive action in mediated political discourse ............................................................................ 6 Tuomo Hiippala (University of Helsinki) ............................................................................................ 7 Communicative situations on social media – a multimodal perspective ........................................ 7 Sirpa Leppänen (University of Jyväskylä) ........................................................................................... 8 Intentional identifications in digital interaction: how semiotization serves in fashioning selves and others ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Julien Longhi (University Cergy-Pontoise) ......................................................................................... 9 Building, exploring and analysing CMC corpora: a pragmatic tool-based approach to political discourse on the internet ................................................................................................................. -

Vlogging the Museum: Youtube As a Tool for Audience Engagement

Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Kris Morrissey Scott Magelssen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Museology ©Copyright 2014 Amanda Dearolph Abstract Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kris Morrissey, Director Museology Each month more than a billion individual users visit YouTube watching over 6 billion hours of video, giving this platform access to more people than most cable networks. The goal of this study is to describe how museums are taking advantage of YouTube as a tool for audience engagement. Three museum YouTube channels were chosen for analysis: the San Francisco Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Field Museum of Natural History. To be included the channel had to create content specifically for YouTube and they were chosen to represent a variety of institutions. Using these three case studies this research focuses on describing the content in terms of its subject matter and alignment with the common practices of YouTube as well as analyzing the level of engagement of these channels achieved based on a series of key performance indicators. This was accomplished with a statistical and content analysis of each channels’ five most viewed videos. The research suggests that content that follows the characteristics and culture of YouTube results in a higher number of views, subscriptions, likes, and comments indicating a higher level of engagement. This also results in a more stable and consistent viewership. -

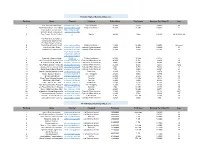

Sources & Data

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

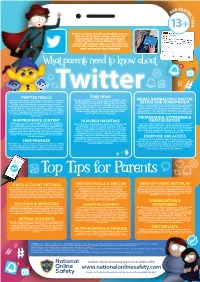

Youtube Is a Video Sharing Site/Application That Enables You to STRIC RE T Upload, View, Rate, Share and Comment on a Wide Variety of E IO Videos

E REST AG R IC T I O N 13 + Twitter is a social networking site where users can post ‘tweets’ or short messages, photos and videos publicly. They can also share ‘tweets’ written by others to their followers. Twitter is popular with young people, as it allows them to interact with celebrities, stay up to date with news, trends and current social relevance. What parents need to know about Twitter TWITTER TROLLS FAKE NEWS A ‘troll’ is somebody who deliberately posts negative or oensive The speed in which ‘tweets’ are shared on Twitter can be MEMES NORMALISING RACISM, comments online in a bid to provoke an individual for a reaction. unbelievably fast, meaning that fake news can often be SEXISM AND HOMOPHOBIA Trolling, can include bullying, harassment, stalking, virtual circulated across the platform very quickly. Fake news articles and posts can often be harmful and upsetting to Twitter is a popular platform for sharing Internet memes, helping to mobbing and much more; it is very common on Twitter. The motive make concepts or ideas go viral across the Internet. However, may be that the ‘troll’ wishes to promote an opinion or make young people and those associated with the fake news. In despite most meme’s being innocent and harmless, some often people laugh, however, the pragmatics of what they post could be addition to this, it’s very easy for people to quickly and include sexist, racist or homophobic messages. Although they are much more damaging, posting anything from racial, homophobic unexpectedly retweet a tweet posted by your child, typically sent as a joke, this type of content is contributing to the to sexist hate. -

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS

Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................... 1 What Techniques Do Media Manipulators Use? ....... 33 Understanding Media Manipulation ............................ 2 Participatory Culture ........................................... 33 Who is Manipulating the Media? ................................. 4 Networks ............................................................. 34 Internet Trolls ......................................................... 4 Memes ................................................................. 35 Gamergaters .......................................................... 7 Bots ...................................................................... 36 Hate Groups and Ideologues ............................... 9 Strategic Amplification and Framing ................. 38 The Alt-Right ................................................... 9 Why is the Media Vulnerable? .................................... 40 The Manosphere .......................................... 13 Lack of Trust in Media ......................................... 40 Conspiracy Theorists ........................................... 17 Decline of Local News ........................................ 41 Influencers............................................................ 20 The Attention Economy ...................................... 42 Hyper-Partisan News Outlets ............................. 21 What are the Outcomes? .......................................... -

After 12 Years in Charge, Superintendent to Retire June 30

The EST. 2009 JANUARY 2020 FIFTY CENTS STUDENT NEWSPAPER of BOONE COUNTY HIGHR SCHOOL EBELLION SPORTS B4 CHEER WINS STATE Cheerleaders dominating season continues with two regional titles and a state championship RRobertButler The Rebels Small Varsity Cheer team won the KHSAA State Championship, Dec. 14, at All Tech Arena in Lexington, KY. The Rebels posted a final score of 96.1 and beat second place Pikeville by more than six points. This win highlights the Rebels dominant run so far this season. Before winning state, they had al- ready won two regional tourna- ments and a state wide tournament. Head coach Michelle Schuster says that there is a lot of pressure being reigning national champs. She hopes that after their state champi- onship they can place top three at nationals later this season. “I am proud of how this team has handled the pressure. They con- tinue to be humble and persevere,” Schuster said. Seniors Ashtyn Fangman, Lanie Fangman, and Madi Monroe all recognize the pressure that comes with winning the national championship, but they say that their team possesses a unique drive and work ethic that allows them to outperform their opponents. MorganDaniels/REBELLIONSTAFF “The best part of being a part of the varsity team this year is that The Rebel small varsity squad emerges for their routine at the KHSAA Region 5 Championship at Boone County High School on Nov. 23. They we have a team that is willing to do eventually went on to win the regional championship that secured their spot in the state tournament. -

Youtube, Multichannel Networks and the Accelerated Evolution of the New Screen Ecology

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Cunningham, Stuart, Craig, David, & Silver, Jon (2016) YouTube, multichannel networks and the accelerated evolution of the new screen ecology. Convergence, 22(4), pp. 376-391. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/98716/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516641620 YouTube, Multichannel Networks and the accelerated evolution of the new screen ecology The concept of ‘connected viewing’ encapsulates deep changes in consumer habit and expectation relating ‘to a larger trend across the media industries to integrate digital technology and socially networked communication with traditional screen media practices’ (Holt & Sanson, 2013: 1).