From Peaceful Militancy to Revolution: an Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the Leader of the National Union of Women’S Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the Largest Women’S Suffrage Organization in Great Britain

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Undergraduate Research Awards Student Scholarship and Creative Works 2012 Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain Cecelia Parks Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Cecelia, "Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain" (2012). Undergraduate Research Awards. 11. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cecelia Parks: Essay When given the assignment to research a women’s issue in modern European history, I chose to study Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the largest women’s suffrage organization in Great Britain. I explored her time as head of this organization and the strategies she employed to become enfranchised, concentrating on the latter part of her tenure. My research was primarily based in two pieces of Fawcett’s own writing: a history of the suffrage movement, Women’s Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement, published in 1912, and her memoir, What I Remember, published in 1925. Because my research focused so much on Fawcett’s own work, I used that writing as my starting point. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

Votes for Women (Birmingham Stories)

Votes for Women: Tracing the Struggle in Birmingham Contents Introduction: Votes For Women in Birmingham The Rise of Women’s Suffrage Societies Birmingham and the Women’s Social and Political Union Questioning The Evidence of Suffragette History in Birmingham Key Information on Suffragette Movements in Birmingham Sources from Birmingham Archives and Heritage Collections General Sources Written by Dr Andy Green, 2009. www.connectinghistories.org.uk/birminghamstories.asp Early women’s Histories in the archive Reports of the Birmingham Women’s Suffrage Society [LF 76.12] Birmingham Branch of the National Council of Women [MS 841] Women Workers Union Reports [L41.2] ‘Suffragettes at Aston Parliament’, Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 17 October 1908. Elizabeth Cadbury Papers Introduction: Votes for Women in Birmingham [MS 466] The women of Birmingham and the rest of Britain only won the right to vote through a long and difficult campaign for social equality. ‘The Representation The Female Society for of the People Bill’ (1918) allowed women over the age of thirty the chance Birmingham for the Relief to participate in national elections. Only when the ‘Equal Franchise Act’ of British Negro Slaves (1928) was introduced did all women finally have the right to take part in [IIR: 62] the parliamentary voting system as equal citizens. For centuries, a sexist opposition to women’s involvement in public life tried Birmingham Association to keep women firmly out of politics. Biological arguments that women were for the Unmarried inferior to men were underlined by sentimental portrayals of women as the Mother and Her Child rightful ‘guardians of the home’. While women from all classes, backgrounds and political opinions continued to work, challenge and support society, [MS 603] their rights were denied by a ‘patriarchal’ or ‘male centred’ British Empire in which men sought to control and dominate politics. -

The Women's Suffrage Movement

The Women’s Suffrage Movement Today, all citizens, living in Northern Ireland, over the age of eighteen share a fundamental human right: the right to vote and to have a voice in the democratic process. One hundred years ago, women in Great Britain and Ireland were not allowed to vote. The Suffrage Movement fought for the right for women to vote and to run for office. This Movement united women from all social, economic, political and religious backgrounds who shared the same goal. The Representation of the People Act in 1832 was led through Parliament by Lord Grey. This legislation, known as the Great Reform Act excluded women from voting because it used the word ‘male’ instead of ‘people’. The first leaflet promoting the Suffrage Movement was published in 1847 and Suffrage societies began to emerge across the country. In 1867, Isabella Tod, who lived in Belfast established the Ladies’ Institute to promote women’s education. She travelled throughout Ireland addressing meetings about Women’s Suffrage. Frustrated by their social and economic situation, Lydia Becker led the formation of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) in 1867. In 1868, Richard Pankhurst, an MP and lawyer from Manchester, made a new attempt to win voting rights for women. While he was unsuccessful, his wife and daughter, Emmeline and Christabel, go on to become two of the most important figures in the movement. In 1897 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was established and Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected as its President. Between 1866 and1902 peaceful activities by NUWSS and others societies led to numerous petitions, bills and resolutions going before the House of Commons. -

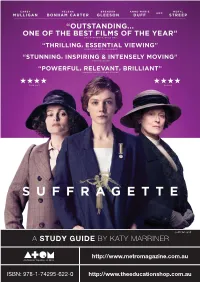

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

The Battle of Equality Contents 1

The Battle Of Equality Contents 1. Contents 2. Women’s Rights 3. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. 4. Suffragettes 5. Suffragists 6. Who didn’t want women’s suffrage 7. Time Line of The Battle of Equality 8. Horse Derby 9. Pictures Woman’s Rights There were two groups that fought for woman's rights, the WSPU and the NUWSS. The NUWSS was set up by Millicent Fawcett. The WSPU was set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The WSPU was created because they didn’t want to wait for women’s rights by campaigning and holding petitions. They got bored so they created the WSPU. The WSPU went to the extreme lengths just to be heard. Whilst the NUWSS jus campaigned for women’s rights. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. Emmeline Pankhurst (suffragette) - Leader of the suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst (suffragette)- Director of the most dangerous suffragette activities Constance Lytton (suffragette)- Daughter of viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton Emily Davison (suffragette)- Killed by kings horse Millicent Fawcett (suffragist)- Leader of the suffragist Edith Garrud (suffragette)- World professional Jiu-Jitsu master Silvia Pankhurst (suffragist)- Focused on campaigning and got expelled from the suffragettes by her sister Ethel Smyth (suffragette)- Conducted the suffragette anthem with a toothbrush Leonora Cohen (suffragette)- Smashed the display case for the Crown Jewels Constance Markievicz (suffragist)- Played a prominent role in ensuring Winston Churchill was defeated in elections Suffragettes The suffragettes were a group of women who wanted to vote. They did dangerous things like setting off bombs. The suffragettes were actually called The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). -

Westminster Pioneering Women

PIONEERING WOMEN OF WESTMINSTER IN WESTMINSTER IN CYCLING START AND FINISH This 10 mile (approx) ride around Westminster introduces us to women that broke the mould! We’ll be hearing about big names like Emmeline Pankhurst and Florence Nightingale as well as lesser known pioneers like the politician Susan Lawrence and the engineer Hertha Ayrton. The circular route takes us down back streets and on quiet roads so that you can relax and enjoy the ride. This is a great way to build confidence cycling in the city whilst learning new fascinating facts. START & FINISH: Tokyobike Fitzrovia, 14 Eastcastle St, London W1T A OCTAVIA HILL (1838-1912) 2 Garbutt Place Octavia was an English social reformer, whose main concern was the welfare of the inhabitants of cities, OCTAVIA HILL PLAQUE especially London. She was key in the fight to save recreational spaces including Vauxhall, Archbishops and Brockwell parks. In 1893 she was one of the three founders who set up the National Trust. B EMMA CONS (1838-1912) 136 Seymour Place In 1880 Emma Cons reopened the Old Vic Theatre to bring Shakespeare and opera to working class communities. She was the first female alderman of the London County Council, however at the time she didn’t have the right to vote! She went on to become very influential in the suffrage movement. EMMA CONS C SARAH SIDDONS (1755-1831) Paddington Green Believed to be the first statue of a non-royal woman erected in London, in 1897. Siddons was a Welsh-born actress known as one of the greatest English tragic actresses. -

Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women's Suffrage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Eckardt Scholars Projects Undergraduate scholarship 5-1-2017 A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917 Gabriele M. Pate Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/undergrad-scholarship-eckardt Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pate, Gabriele M., "A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917" (2017). Eckardt Scholars Projects. 20. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/undergrad-scholarship-eckardt/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate scholarship at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eckardt Scholars Projects by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 A Woman’s Weapon: Hunger Strikes and Force Feedings in the British Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1903-1917 Gaby Pate Senior Honors Thesis Spring 2017 Amardeep Singh 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Context for the Founding of the WSPU .......................................................................................... 5 The “Suffrage Army” ..................................................................................................................... -

Strange Science: Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Strange Science Revised Pages Revised Pages Strange Science Investigating the Limits of Knowledge in the Victorian Age ••• Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett editors University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2017 by Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2020 2019 2018 2017 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Karpenko, Lara Pauline, editor. | Claggett, Shalyn R., editor. Title: Strange science : investigating the limits of knowledge in the Victorian Age / Lara Karpenko and Shalyn Claggett, editors. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Anonymous, “Women's Suffrage: The Right to The Vote”, n.d. This image shows an example of a poster that supported the Suffragettes’ cause. There have been numerous posters with a similar design. On this poster is Joan of Arc, an important figure to the Suffragettes, holding a banner that says “The Right to The Vote”. “ALL THE SUFFRAGIST LEADERS ARRESTED: “WE WILL ALL STARVE TO DEATH IN PRISON UNLESS WE ARE FORCIBLY FED”” The Daily Sketch, http://www.spirited.org.uk/object/daily-sketch-shows-the-method-used-for-force-feeding-suf fragettes This is an image of a newspaper during the force-feeding of Suffragettes. This image describes the strength and sacrifice that Suffragettes were willing to make. Barratt's Photo Press Ltd. “Suffragette Struggling with a Policeman on Black Friday.” The Museum of London, London , 14 Nov. 2018, www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/black-friday. This photograph was taken during the police brutality during protests against the failure of the Conciliation Bill. It was compiled by Barratt’s Photo Press Ltd. in 1910. Bathurst, G. “The National Archives .” Received by First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works, The National Archives , 6 Apr. 1910. WORK 11/117, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/suffragettes-on-file/hiding-in-parliament/. This was a letter written by G. Bathurst, Chief Clark of the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, to inform the First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works about the actions of Emily Wilding Davison. Emily Wilding Davison was an important Suffragette who eventually became the Suffragette martyr in 1913 when she ran in front of the King’s horse during a derby. -

A Prostitution of the Profession?: the Ethical Dilemma of Suffragette

22-4-2020 ‘A Prostitution of the Profession’?: The Ethical Dilemma of Suffragette Force-Feeding, 1909–14 - A History of Force Feeding - NCBI … NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Miller I. A History of Force Feeding: Hunger Strikes, Prisons and Medical Ethics, 1909-1974. Basingstoke (UK): Palgrave Macmillan; 2016 Aug 26. Chapter 2 ‘A Prostitution of the Profession’?: The Ethical Dilemma of Suffragette Force-Feeding, 1909–14 In 2013, the British Medical Association wrote to President Obama and US Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel inveighing against force-feeding policies at Guantánamo Bay. The Association was deeply concerned with the ethical problems associated with feeding prisoners against their will, seeing this as a severe violation of medical ethics. To support its emotive claims, the Association pointed to the Declarations of Tokyo (1975) and Malta (1991) which had 1 both clearly condemned force-feeding as unethical. Nonetheless, American military authorities had resurrected the practice, the Association suggested, to avoid facing an embarrassing set of prison deaths that risked turning 2 international opinion against Guantánamo and the nature of its management. Like other critics, the Association had some compassion for military doctors who seemed to be caught in an unhappy dilemma: Should they prevent suicides by force-feeding or oversee slow, excruciating deaths from starvation? Yet despite showing empathy, critics from within the medical profession, such as British general