The, Suffragette Movement in Great Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760

Issue 61 Autumn/Winter 2009 Issn 1476-6760 Faridullah Bezhan on Gender and Autobiography Rosalind Carr on Scottish Women and Empire Nicola Cowmeadow on Scottish Noblewomen’s Political Activity in the 18th C Katie Barclay on Family Legacies Huw Clayton on Police Brutality Allegations Plus Five book reviews Call for Reviewers Prizes WHN Conference Reports Committee News www.womenshistorynetwork.org Women’s History Network 19th Annual Conference 2009 Performing the Self: Women’s Lives in Historical Perspective University of Warwick, 10-12 September 2010 Papers are invited for the 19th Annual Conference 2010 of the Women’s History Network. The idea that selfhood is performed has a very long tradition. This interdisciplinary conference will explore the diverse representations of women’s identities in the past and consider how these were articulated. Papers are particularly encouraged which focus upon the following: ■ Writing women’s histories ■ Gender and the politics of identity ■ Ritual and performance ■ The economics of selfhood: work and identity ■ Feminism and auto/biography ■ Performing arts ■ Teaching women’s history For more information please contact Dr Sarah Richardson: [email protected], Department of History, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL. Abstracts of papers (no more than 300 words) should be submitted to [email protected] The closing date for abstracts is 5th March 2010. Conference website: www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/res_rec/ conferences/whn Further information and a conference call will be posted on the WHN website www.womenshistorynetwork.org Editorial elcome to the Autumn/Winter 2009 edition of reproduced in full. We plan to publish the Carol Adams WWomen’s History Magazine. -

Suffragette: the Battle for Equality Author/ Illustrator: David Roberts Publisher: Two Hoots (2018)

cilip KATE GREENAWAY shortlist 2019 shadowing resources CILIP Kate Greenaway Medal 2019 VISUAL LITERACY NOTES Title: Suffragette the Battle for Equality Author/ Illustrator: David Roberts Publisher: Two Hoots First look This is a nonfiction book about the women and men who fought for women’s rights at the beginning of the 20th Century. It is packed with information – some that we regularly read or hear about, and some that is not often highlighted regarding this time in history. There may not be time for every shadower to read this text as it is quite substantial, so make sure they have all shared the basic facts before concentrating on the illustrations. Again, there are a lot of pictures so the following suggestions are to help to navigate around the text to give all shadowers a good knowledge of the artwork. After sharing a first look through the book ask for first responses to Suffragette before looking in more detail. Look again It is possible to group the illustrations into three categories. Find these throughout the book; 1. Portraits of individuals who either who were against giving women the vote or who were involved in the struggle. Because photography was becoming established we can see photos of these people. Some of them are still very well-known; for example, H.H. Asquith, Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916 and Winston Churchill, Home Secretary from 1910 to 1911. They were both against votes for women. Other people became well-known because they were leading suffragettes; for example, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney. 2. -

Fair Measure of the Right to Vote: a Comparative Perspective on Voting Rights Enforcement in a Maturing Democracy

SCHOOL OF LAW LEGAL STUDIES RESEARCH PAPER SERIES PAPER #10-0186 JUNE 2010 FAIR MEASURE OF THE RIGHT TO VOTE: A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE ON VOTING RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT IN A MATURING DEMOCRACY JANAI S. NELSON EMAIL COMMENTS TO: [email protected] ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 8000 UTOPIA PARKWAY QUEENS, NY 11439 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection http://ssrn.com/abstract=1628798 DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION OF AUTHOR ———————————————————————————————————— FAIR MEASURE OF THE RIGHT TO VOTE ———————————————————————————————————— Fair Measure of the Right to Vote: A Comparative Perspective on Voting Rights Enforcement in a Maturing Democracy Janai S. Nelson ABSTRACT Fair measure of a constitutional norm requires that we consider whether the scope of the norm can be broader than its enforcement. This query is usually answered in one of two ways: some constitutional theorists argue that the scope and enforcement of the norm are co-terminous, while others argue that the norm maintains its original scope and breadth even if it is underenforced. This Article examines the right to vote when it exists as a constitutional norm and is underenforced by both judicial and non-judicial actors. First, I adopt the position that the scope and meaning of a constitutional norm can be greater than its enforcement. Second, I rely on the argument that underenforcement results not only from judicial underenforcement but also from underenforcement by the legislative and administrative actors that are obligated to enforce constitutional norms to the fullest extent. By employing these two principles, this Article analyzes the underenforcement of the right to vote that has evaded the force of some of the most liberal contemporary constitutions. -

De Facto Disenfranchisement

DE FACTO DISENFRANCHISEMENT Erika Wood and Rachel Bloom American Civil Liberties Union and Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the american civil liberties union The American Civil Liberties Union is the nation’s premier guardian of liberty, working daily in courts, legislatures and communities to defend and preserve the individual rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution and the laws of the United States. about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution – part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group – the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advo- cacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. © 2008. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law and the ACLU are credited, a link to the each organization’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s and ACLU’s permission. Please let the Brennan Center and the ACLU know if you reprint. -

A Virtual Museum by Imogen Wilson Welcome to the Virtual Museum St Peter’S Field 1819

TheThe extensionextension ofof suffragesuffrage A virtual museum by imogen wilson Welcome to the virtual museum St Peter’s field 1819 August 16th 1819 slaves and female reformers Insert a picture of a person, object, or place, or gathered together as a peaceful crowd of about write a story you would include in your museum. 60,000 at St Peters Field in Manchester, to protest for all men over the age of 21 to be able to vote. Men and women both protested. Even though they were only protesting for men’s rights the women thought that having a household member who could vote could make a big difference on matters such as income, wages, and working conditions. Changes were introduced in 1832 which began to give more people a voice in politics in britain. Around 50 years later in 1884, there was a big step forward as the amount of men that could vote had tripled. Womens suffrage campaigners They wanted education for women and a vote for women too. They wanted the vote because they believed this would help improve the position and lives of women. They used methods like speeches and lectures to help campaigns. They were unsuccessful because even if they did get the vote, only women who owned a certain amount of property could vote. They really emphasised the issue which raised a lot of awareness and stated the fact that women should have the rights to vote. There were many disagreements amongust the different campaigners. There disagreements included whether women should be granted the vote on the same terms as men. -

Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the Leader of the National Union of Women’S Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the Largest Women’S Suffrage Organization in Great Britain

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Undergraduate Research Awards Student Scholarship and Creative Works 2012 Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain Cecelia Parks Hollins University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Parks, Cecelia, "Millicent Garrett aF wcett: Leader of the Constitutional Women's Suffrage Movement in Great Britain" (2012). Undergraduate Research Awards. 11. https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/researchawards/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at Hollins Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Hollins Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cecelia Parks: Essay When given the assignment to research a women’s issue in modern European history, I chose to study Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), the largest women’s suffrage organization in Great Britain. I explored her time as head of this organization and the strategies she employed to become enfranchised, concentrating on the latter part of her tenure. My research was primarily based in two pieces of Fawcett’s own writing: a history of the suffrage movement, Women’s Suffrage: A Short History of a Great Movement, published in 1912, and her memoir, What I Remember, published in 1925. Because my research focused so much on Fawcett’s own work, I used that writing as my starting point. -

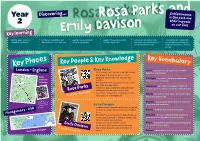

Rosa Parks and Emily Davison

Year Achievements Discovering... in the past and 2 Rosa Parks andtheir impacts Emily Davison on our lives Key learning Identify what makes an Recognise similarities and Explain how Rosa Parks Explain how Emily Davison Recognise similarities and Understand and explain the individual significant. differences to 1955 and now. became significant. became significant. differences about RP and ED impact that Rosa Parks and and their achievements. Emily Davison had on modern society. Key Vocabulary Key Places Key People & Key Knowledge Rosa Parks Activist – a person who campaigns to bring about London - England • Civil rights activist in the mid to late 20th Century. political or social change. • She refused to give up her seat to a white Emily passenger on December 1st, 1955 and was Civil Rights – the rights of citizens to political and Davison’s arrested. social freedom and equality. birthplace • This launched the Montgomery bus boycott (5th Dec, 1995-20th Dec, 1996) Segregation – the enforced separation of different • At this time, black people were segregated and racial groups in a country, community or establishment. discriminated for the colour of their skin. Rosa Parks • Rosa Parks changed laws on segregation in the Equality – the state of being equal, especially in status. Feb 4, 1913 – Oct 24, 2005 USA, starting with transportation. Rights and opportunities. Carlisle Park, Prejudice – preconceived opinion that is not based on Northumberland reason or actual experience. – Statue of Emily Emily Davison Davison • A women’s equal rights activist who quit her job as a teacher to join the Women’s Social and Political Boycott – withdraw from something in protest. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

THE LEAGUE of WOMEN VOTERS® of CENTRAL NEW MEXICO 2501 San Pedro Dr. NE, Suite 216 Albuquerque, NM 87110-4158

August 2020 The VOTER Vol. 85 No. 8 ® THE LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF CENTRAL NEW MEXICO 2501 San Pedro Dr. NE, Suite 216 Albuquerque, NM 87110-4158 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State because of sex. On this occasion of the 100th anniversary of women securing the right to vote in the United States, the League of Women Voters of Central New Mexico proudly dedicates this issue to all of the women and men who fought for over 70 years to achieve women’s suffrage...a right which women today should never take for granted… a right which we should recognize took many more years to be equally available to women of color… and a right which even today is being suppressed in many States. As we re-dedicate ourselves to righting those wrongs, let us celebrate this milestone during this 100th anniversary month. SEE PAGE 12 FOR INFORMATION ABOUT THE AUGUST 13, 2020 ZOOM UNIT MEETING FEATURING PRESENTATIONS ABOUT THE FIGHT FOR WOMEN SUFFRAGE BY MEREDITH MACHEN AND JEANNE LOGSDON. THE VOTER page 2 A SUFFRAGE TIMELINE from the New Mexico perspective 1848 First Women's Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls, NY passes resolution calling for full voting rights for women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton authors the Declaration of Sentiments. 1868 The 14th amendment ratified, using “male” in the Constitution, thereby deny- ing women the right to vote. 1869 National Woman Suffrage Association works state by state to get women the vote. -

Votes for Women (Birmingham Stories)

Votes for Women: Tracing the Struggle in Birmingham Contents Introduction: Votes For Women in Birmingham The Rise of Women’s Suffrage Societies Birmingham and the Women’s Social and Political Union Questioning The Evidence of Suffragette History in Birmingham Key Information on Suffragette Movements in Birmingham Sources from Birmingham Archives and Heritage Collections General Sources Written by Dr Andy Green, 2009. www.connectinghistories.org.uk/birminghamstories.asp Early women’s Histories in the archive Reports of the Birmingham Women’s Suffrage Society [LF 76.12] Birmingham Branch of the National Council of Women [MS 841] Women Workers Union Reports [L41.2] ‘Suffragettes at Aston Parliament’, Birmingham Weekly Mercury, 17 October 1908. Elizabeth Cadbury Papers Introduction: Votes for Women in Birmingham [MS 466] The women of Birmingham and the rest of Britain only won the right to vote through a long and difficult campaign for social equality. ‘The Representation The Female Society for of the People Bill’ (1918) allowed women over the age of thirty the chance Birmingham for the Relief to participate in national elections. Only when the ‘Equal Franchise Act’ of British Negro Slaves (1928) was introduced did all women finally have the right to take part in [IIR: 62] the parliamentary voting system as equal citizens. For centuries, a sexist opposition to women’s involvement in public life tried Birmingham Association to keep women firmly out of politics. Biological arguments that women were for the Unmarried inferior to men were underlined by sentimental portrayals of women as the Mother and Her Child rightful ‘guardians of the home’. While women from all classes, backgrounds and political opinions continued to work, challenge and support society, [MS 603] their rights were denied by a ‘patriarchal’ or ‘male centred’ British Empire in which men sought to control and dominate politics. -

The Women's Suffrage Movement

The Women’s Suffrage Movement Today, all citizens, living in Northern Ireland, over the age of eighteen share a fundamental human right: the right to vote and to have a voice in the democratic process. One hundred years ago, women in Great Britain and Ireland were not allowed to vote. The Suffrage Movement fought for the right for women to vote and to run for office. This Movement united women from all social, economic, political and religious backgrounds who shared the same goal. The Representation of the People Act in 1832 was led through Parliament by Lord Grey. This legislation, known as the Great Reform Act excluded women from voting because it used the word ‘male’ instead of ‘people’. The first leaflet promoting the Suffrage Movement was published in 1847 and Suffrage societies began to emerge across the country. In 1867, Isabella Tod, who lived in Belfast established the Ladies’ Institute to promote women’s education. She travelled throughout Ireland addressing meetings about Women’s Suffrage. Frustrated by their social and economic situation, Lydia Becker led the formation of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage (NSWS) in 1867. In 1868, Richard Pankhurst, an MP and lawyer from Manchester, made a new attempt to win voting rights for women. While he was unsuccessful, his wife and daughter, Emmeline and Christabel, go on to become two of the most important figures in the movement. In 1897 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was established and Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected as its President. Between 1866 and1902 peaceful activities by NUWSS and others societies led to numerous petitions, bills and resolutions going before the House of Commons. -

The Battle of Equality Contents 1

The Battle Of Equality Contents 1. Contents 2. Women’s Rights 3. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. 4. Suffragettes 5. Suffragists 6. Who didn’t want women’s suffrage 7. Time Line of The Battle of Equality 8. Horse Derby 9. Pictures Woman’s Rights There were two groups that fought for woman's rights, the WSPU and the NUWSS. The NUWSS was set up by Millicent Fawcett. The WSPU was set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The WSPU was created because they didn’t want to wait for women’s rights by campaigning and holding petitions. They got bored so they created the WSPU. The WSPU went to the extreme lengths just to be heard. Whilst the NUWSS jus campaigned for women’s rights. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. Emmeline Pankhurst (suffragette) - Leader of the suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst (suffragette)- Director of the most dangerous suffragette activities Constance Lytton (suffragette)- Daughter of viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton Emily Davison (suffragette)- Killed by kings horse Millicent Fawcett (suffragist)- Leader of the suffragist Edith Garrud (suffragette)- World professional Jiu-Jitsu master Silvia Pankhurst (suffragist)- Focused on campaigning and got expelled from the suffragettes by her sister Ethel Smyth (suffragette)- Conducted the suffragette anthem with a toothbrush Leonora Cohen (suffragette)- Smashed the display case for the Crown Jewels Constance Markievicz (suffragist)- Played a prominent role in ensuring Winston Churchill was defeated in elections Suffragettes The suffragettes were a group of women who wanted to vote. They did dangerous things like setting off bombs. The suffragettes were actually called The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).