CATALAN NATIONALISM: a SHIFT from CIVIC to ETHNIC Ahmed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

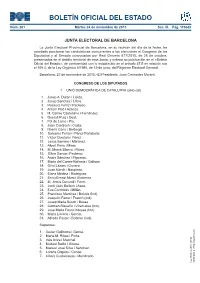

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

Independentism and the European Union

POLICY BRIEF 7 May 2014 Independentism and the European Union Graham Avery Independentism1 is a live issue in Europe today. In the European Union separatist parties have gained votes in Scotland, Catalonia, Flanders and elsewhere2, and referendums are in prospect. In Eastern Europe Crimea's referendum has led to an international crisis. This note addresses some basic questions raised by these developments: • What is the European Union's policy on independentism? • Is the division of a member state into two states bad for the EU? • How is the organisational structure of the EU relevant to independentism? BACKGROUND The situation on the ground in the EU today may be summarised as follows: Scotland: a referendum on independence will take place in Scotland on 18 September 2014. The Scottish National Party, which won a majority of seats in the Scottish elections of 2011 and formed a government, is campaigning for 'yes'. Although the British parliament agreed to the referendum, the main political parties in London are campaigning for 'no'. Opinion polls show that 'no' has more supporters than 'yes', but the gap has diminished, many voters are undecided, and the result may be close.3 Catalonia: in regional elections in 2012 the alliance Convergence and Union (Convergència i Unió) won 31% of the vote and formed a coalition government, which has announced a referendum on independence for 9 November 2014. Since Spain's Parliament has declared it unconstitutional, the referendum may not take place. But the next regional elections may effectively become a substitute for a referendum. Belgium: the New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) gained ground in national elections in 2010 on a platform of independence for Flanders. -

The Catalan Struggle for Independence

THE CATALAN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE An analysis of the popular support for Catalonia’s secession from Spain Master Thesis Political Science Specialization: International Relations Date: 24.06.2019 Name: Miquel Caruezo (s1006330) Email: [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Angela Wigger Image Source: Photo by NOTAVANDAL on Unsplash (Free for commercial or non-commercial use) Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ......................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Resource Mobilization Theory ...................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1 Causal Mechanisms ................................................................................................................ 9 1.1.2 Hypotheses........................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Norm Life Cycle Theory ............................................................................................................... 11 1.2.1 Causal Mechanisms ............................................................................................................. -

Reclaiming Their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies

Reclaiming their Shadow: Ethnopolitical Mobilization in Consolidated Democracies Ph. D. Dissertation by Britt Cartrite Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder May 1, 2003 Dissertation Committee: Professor William Safran, Chair; Professor James Scarritt; Professor Sven Steinmo; Associate Professor David Leblang; Professor Luis Moreno. Abstract: In recent decades Western Europe has seen a dramatic increase in the political activity of ethnic groups demanding special institutional provisions to preserve their distinct identity. This mobilization represents the relative failure of centuries of assimilationist policies among some of the oldest nation-states and an unexpected outcome for scholars of modernization and nation-building. In its wake, the phenomenon generated a significant scholarship attempting to account for this activity, much of which focused on differences in economic growth as the root cause of ethnic activism. However, some scholars find these models to be based on too short a timeframe for a rich understanding of the phenomenon or too narrowly focused on material interests at the expense of considering institutions, culture, and psychology. In response to this broader debate, this study explores fifteen ethnic groups in three countries (France, Spain, and the United Kingdom) over the last two centuries as well as factoring in changes in Western European thought and institutions more broadly, all in an attempt to build a richer understanding of ethnic mobilization. Furthermore, by including all “national -

Europa L’Entrevista Ja Som a L’Estiu I Moltes De De La Nostra Voluntat

La Veu Butlletí de Reagrupament Independentista Europa L’entrevista Ja som a l’estiu i moltes de de la nostra voluntat. Europa les esperances de la primavera ens espera com un estat més i Dr. Moisès Broggi: ja no les tenim... només depèn de nosaltres de Una esperança: que el voler-ne ser protagonistes. “Cada vegada hi ha Parlament Europeu fos El company Jordi Gomis ho menys arguments competent per regular el tenia molt clar, i com ell va dret de ciutadania de la UE; deixar escrit: «És una obvietat per continuar sent una altra: que la situació que si Catalunya fos un Estat, part d’un estat que econòmica no ens endinsés no tindríem espoli fiscal, i en un pou de la mà de la per tant, els recursos dels que ens ofega” incompetència espanyola. disposem es multiplicarien PÀGINA 4 La Comissió Europea ens automàticament. Més enllà de ha dit que el Parlament no desempallegar-nos d’un Estat és competent per regular que xucla els nostres recursos Recordem Jordi Gomis sobre la ciutadania europea, i ens ofega econòmicament, Un altre Franco però ens ha indicat dos fets les dades també demostren molt importants: admet la que els estats petits de la UE Dèficits i balances possibilitat de secessió d’una han crescut molt per sobre fiscals part d’un Estat membre i que els grans, prenent les considera la solució en la dades que van des del 1979 /&(- negociació dins l’ordenament fins els nostres dies... En jurídic internacional. definitiva, tenim dues opcions: D’aquesta forma la Comissió esperar que després de 23 Resultats de 30 anys Europea desmenteix les anys -

Catalonia, Spain and Europe on the Brink: Background, Facts, And

Catalonia, Spain and Europe on the brink: background, facts, and consequences of the failed independence referendum, the Declaration of Independence, the arrest and jailing of Catalan leaders, the application of art 155 of the Spanish Constitution and the calling for elections on December 21 A series of first in history. Examples of “what is news” • On Sunday, October 1, Football Club Barcelona, world-known as “Barça”, multiple champion in Spanish, European and world competitions in the last decade, played for the first time since its foundation in 1899 at its Camp Nou stadium, • Catalan independence leaders were taken into custody in “sedition and rebellion” probe • Heads of grassroots pro-secession groups ANC and Omnium were investigated over September incidents Results • Imprisonment of Catalan independence leaders gives movement new momentum: • Asamblea Nacional Catalana (Jordi Sànchez) and • Òmnium Cultural (Jordi Cuixart), • Thousands march against decision to jail them • Spain’s Constitutional Court strikes down Catalan referendum law • Key background: • The Catalan Parliament had passed two laws • One would attempt to “disengage” the Catalan political system from Spain’s constitutional order • The second would outline the bases for a “Republican Constitution” of an independent Catalonia The Catalan Parliament factions • In the Parliament of Catalonia, parties explicitly supporting independence are: • Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català (Catalan European Democratic Party; PDeCAT), formerly named Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya -

Facultad De Derecho Grado En Derecho

Facultad de Derecho Grado en Derecho Impugnación ante el Tribunal Constitucional de los actos del Parlament de Catalunya relativos al proceso "soberanista" Presentado por: Jónatan Pérez Diéguez Tutelado por: Juan Fernando Durán Alba Valladolid, 13 de julio de 2018 1 RESUMEN Durante esta última década, se ha ido expandiendo por la Comunidad Autónoma de Cataluña una corriente independentista que ha ido irrumpiendo cada vez con más fuerza tanto en las calles como en las instituciones políticas. Al mismo ritmo, el Parlament de Catalunya ha ido aprobando, con el apoyo de las fuerzas políticas más nacionalistas, una serie de actos, encuadrados en una “hoja de ruta”, con los que ha tratado de ir construyendo unas “estructuras de Estado” cuyo último fin era la independencia de Cataluña del Estado Español. Este Trabajo de Fin de Grado, por tanto, aborda los distintos procesos constitucionales que se han ido utilizando como vía a la impugnación de estos actos ante el Tribunal Constitucional, para salvaguardar los valores propios que garantiza la Constitución Española. Palabras clave: Constitución Española, Parlamento de Cataluña, Ley, Resolución, recurso de inconstitucionalidad, impugnación, recurso de amparo, sentencia, Tribunal Constitucional. ABSTRACT During this last decade, it has been expanding in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia, a pro-independence movement that has been breaking with increasing force both in the streets and in political institutions. At the same pace, the Catalonia’s Parliament has been approving, with the support of the most nationalist political forces, a series of acts, fitted in a "road map", with which they have tried to build "State structures" whose last purpose was the independence of Catalonia from the Spanish State. -

Cal Seguir Endavant

Sumari La Veu Internacional Butlletí de Reagrupament Independentista Afers exteriors: el Diplocat per Josep Sort Cal seguir endavant PÀGINA 2 Municipalisme Segons l’acord de legislatura polítics de Catalunya ens pot Homilies contra entre CIU i ERC, el dia 30 de abocar a una gran decepció Lapao juny d’enguany caldria haver ciutadana. El President demanat l’autorització al Mas va entrar a la ratera el per Carles Bonaventura govern espanyol per a dur a 25N i, cada dia que passa, PÀGINA 3 terme la “consulta”. Qualsevol està més atrapat en la seva persona amb un sentit mínim solitud. El cap de l’oposició/ Cultura de la lògica interpreta que soci de govern està encantat això vol dir haver aprovat veient com es dessagna el Qui decideix? una pregunta clara i una govern, amb la pretensió per Montserrat Tudela data. És una obvietat que a única i exclusiva de fer el mig mes de juny no hi ha sorpasso i, es suposa, liderar PÀGINA 4 aprovada ni una pregunta una comunitat autònoma ni una data. Sembla que el arruïnada i exhausta. Cal Territorials President de la Generalitat una feina conjunta dels dóna per fet el tràmit de partits que volen la llibertat Encara cal picar petició al govern espanyol del poble de Catalunya molta pedra d’autorització de la realització i deixar per a d’altres per Xavier Todó del procés de consultar al temps els seus interessos poble de Catalunya quina és partidistes. Cal unitat d’acció PÀGINA 5 la seva voluntat de futur. És, i generositat. Vull recordar, amb perdó, President, una un cop més, que cap govern La ploma convidada broma de molt mal gust. -

Manifest Sobre El Reagrupament Familiar

MANIFEST Davant les reiterades notícies i declaracions respecte a possibles modificacions de la Llei sobre drets i llibertats dels estrangers a Espanya i la seva integració social i el Reglament que la desenvolupa, pel que fa a les condicions pel Reagrupament Familiar, la Comissió Permanent del Consell Municipal d’Immigració de Barcelona, vol manifestar: 1. El dret al reagrupament familiar està recollit en l’ordenament jurídic de la Unió Europea Aquest dret està emparat en la directiva 2003/86/CE del Consell del Unió Europea de 22 de setembre de 2003 sobre el dret al reagrupament familiar. Així mateix el dret a la família esta reconegut en el nostre ordenament jurídic, pels articles 18 i 32 de la Constitució Espanyola, per l’article 16 de la Llei sobre drets i llibertats dels estrangers a Espanya i la seva integració social; També és un dret reconegut per la Carta dels Drets Humans i per la Convenció de Roma. 2. La possibilitat de restringir el reagrupament dels ascendents de les persones immigrades és una mesura que no afavorirà l’arrelament i la cohesió social i que, per altra banda, tindrà poca incidència real en el conjunt de la població. El reagrupament familiar d’ascendents ve a fer una funció necessària per la cohesió social, ajuda a l’arrelament i permet consolidar els nuclis familiars. Actualment el reagrupament d’ascendents ja és molt minoritari – al voltant del 9% del total de sol·licituds – a més a la ciutat de Barcelona afecta especialment a persones de nacionalitat espanyola. Els actuals requisits ja limiten el reagrupament d’ascendents a persones, en general, de més de 65 anys sempre i quan es demostri que l’ascendent reagrupat té una dependència econòmica absoluta respecte al reagrupant. -

Those Who Came and Those Who Left the Territorial Politics of Migration

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository Department of Political and Social Sciences Those who came and those who left The Territorial Politics of Migration in Scotland and Catalonia Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, February 2012 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of Political and Social Sciences Those who came and those who left The Territorial Politics of Migration in Scotland and Catalonia Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Rainer Bauböck, EUI (Supervisor) Prof. Michael Keating, EUI (Co-supervisor) Dr Nicola McEwen, University of Edinburgh Prof. Andreas Wimmer, UCLA © 2012, Jean-Thomas Arrighi de Casanova No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author ABSTRACT Whilst minority nationalism and migration have been intensely studied in relative isolation from one another, research examining their mutual relationship is still scarce. This dissertation aims to fill this gap in the literature by exploring how migration politics are being fought over not only across society but also across territory in two well-researched cases of protracted nationalist mobilisation, Catalonia and Scotland. It meets three objectives: First, it introduces a theoretical framework accounting for sub-state elites’ and administrations’ boundary-making strategies in relation to immigrants and emigrants. -

New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain • Carsten Jacob Humlebæk and Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain

New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain in Nationalism on Perspectives New • Carsten Humlebæk Jacob and Antonia María Jiménez Ruiz New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain Edited by Carsten Jacob Humlebæk and Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Genealogy www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain Editors Carsten Humlebæk Antonia Mar´ıaRuiz Jim´enez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Carsten Humlebæk Antonia Mar´ıa Ruiz Jimenez´ Copenhagen Business School Universidad Pablo de Olavide Denmark Spain Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Genealogy (ISSN 2313-5778) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy/special issues/perspective). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-082-6 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-083-3 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Differentiating Pro-Independence Movements in Catalonia and Galicia: a Contemporary View

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY School of Business and Governance Department of Law Anna Joala DIFFERENTIATING PRO-INDEPENDENCE MOVEMENTS IN CATALONIA AND GALICIA: A CONTEMPORARY VIEW Bachelor’s thesis Programme: International Relations Supervisor: Vlad Alex Vernygora, MA Tallinn 2018 I declare that I have compiled the paper independently and all works, important standpoints and data by other authors have been properly referenced and the same paper has not been previously been presented for grading. The document length is 9222 words from the introduction to the end of summary. Anna Joala …………………………… (signature, date) Student code: 113357TASB Student e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Vlad Alex Vernygora, MA: The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of the Defence Committee: Permitted to the defence ………………………………… (name, signature, date) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 5 1. EXPLANATORY THEORY OF SECESSIONISM ............................................................... 8 1.1. Definition of secessionism ................................................................................................ 8 1.2. Sub-state nationalism .......................................................................................................