Worcestershire Has Fluctuated in Size Over the Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Branches of the Bank of England

BRANCHES OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND Origin of Soon after the foundation end of the year seventy-three of the more the branches of the Bank of England in important banks in England and Wales had 1694, an anonymous writer on financial matters suspended payment. suggested that the Bank should establish In January 1826, with bank failures and branches which would be able to remit"multi commercial bankruptcies still continuing, the tudes of sums, great and small, to and from Court of Directors appointed a Committee to place to place ...without charges of carriage or consider and report "how far it may be dangers of Robberie" (Proposals for National practicable to establish branch banks ". Banks, 1696). The theme was taken up again Although the Committee were primarily con in 1721 by a pamphleteer who advocated the cerned to prevent a recurrence of the difficulties opening of branches "in the trading places of the previous year, they clearly did not over of the nation" whose managers would have look commercial considerations. Perhaps it authority "to lend a little". Such advice was because the latter issue, at least, was met with little response. Apart from introducing reasonably clear-cut that the Committee were Bank Post Bills(a) in 1724, in an attempt to able to report in only a week that they favoured reduce the risks to the mails of highway rob t e setting up of branches which, they con b ry, the Bank were little concerned during the � � SIdered, would greatly increase the Bank's own eIghteenth century with developments in the note circulation, would give the Bank greater financial system outside London and indeed control over the whole paper circulation, and were then frequently referred to as the ' Bank would protect the Bank against competition if of London '. -

UNIT 4, FIELD BARN FARM, FIELD BARN LANE, CROPTHORNE , WR10 3LY Rent

UNITUNIT 4,4, FIELDFIELD BARNBARN FARM,FARM, FIELDFIELD BARNBARN LANE,LANE, CROPTHORNE CROPTHORNE, , WR10WR10 3LY3LY Industrial warehouse with office space TO LET extending to 114.95sq m (1237sq ft) ground floor with an additional 93.3sq m (1004sq ft) of mezzanine floor area on site car parking and staff facilities Rent: £6,500 Per annum 1-3 MERSTOW GREEN • EVESHAM • WORCS • WR11 4BD COMMERCIAL TEL: 01386 765700 EMAIL : [email protected] Website address: www.timothylea-griffiths.co.uk UNIT 4, FIELD BARN FARM, FIELD BARN LANE, CROPTHORNE , WR10 3LY TENURE IMPORTANT NOTES LOCATION The unit is available on a new lease with an Services, fixtures, equipment, buildings and land. None of these have been tested by Timothy Lea & Griffiths. An interested Units 3 and 4 Field Barn Farm are located anticipated term of between 3-5 years party will need to satisfy themselves as to the type, condition and within the village of Cropthorne, approximately suitability for a purpose. 4.5 miles distant from Pershore Town Centre BUSINESS RATES Value Added Tax, VAT may be payable on the purchase price and approximately 3.5 miles distant from the This unit is to be re-assessed and/or the rent and/or any other charges or payments detailed market town of Evesham. Cropthorne is an above. All figures quoted exclusive of VAT. Intending attractive rural village situated off the main LOCAL AUTHORITY purchasers and lessees must satisfy themselves as to the B4084 road linking Evesham to Pershore. The Wychavon District Council applicable VAT position, if necessary, by taking appropriate professional advice. -

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

Sodomy, the Courts and the Civic Idiom in Eighteenth-Century Bristol

Urban History, 34, 1 (2007) C 2007 Cambridge University Press Printed in the United Kingdom doi:10.1017/S0963926807004385 ‘Bringing great shame upon this city’: sodomy, the courts and the civic idiom in eighteenth-century Bristol STEVE POOLE∗ School of History, University of the West of England, Bristol, St Matthias Campus, Bristol BS16 2JP abstract: During the 1730s, Bristol acquired an unenviable reputation as a city in which sodomy was endemic and rarely punished by the civil power. Although the cause lay partly in difficulties experienced in securing convictions, the resolve of magistrates was exposed to fierce scrutiny.Taking an effusive curate’s moral vindication of the city as a starting point, this article examines the social production of sodomy in eighteenth-century Bristol, analyses prosecution patterns and considers the importance of collective moral reputation in the forging of civic history. The Saints Backsiding In 1756, Emanuel Collins, curate, schoolmaster and doggerel poet, penned an extraordinary moral vindication of the city of Bristol, following the public disclosure of a pederasty scandal in the Baptist College and the flight of a number of suspects. In a rare flash of wit, he entitled it, The Saints Backsiding. Not for the first time, it appeared, Collins’ home city was being whispered about elsewhere as a place in which sodomitical transgression was both endemic and unpunished. ‘I am not unacquainted with the many foul reflections that have been cast on my Fellow-Citizens of BRISTOL concerning this most abominable vice’, Collins began, but ‘tis the fate of all cities to be the conflux of bad men.’ They go there ‘to hide themselves in the multitude and to seek security in the crowd’. -

The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Pershore Worcestershire WR10 3LE Guide Price £325,000

14 Broad Street, Pershore, Worcestershire WR10 1AY Telephone: 01386 555368 [email protected] The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Pershore Worcestershire WR10 3LE For Sale by Private Treaty Guide Price £325,000 A THREE BEDROOM INTERESTING PERIOD DWELLING BEING PART OF A DIVIDED FARMHOUSE OFFERING CHARACTER ACCOMMODATION WITH EXPOSED TIMBERS, WOOD BURNING STOVES AND FARMHOUSE KITCHEN Entrance Hallway, Cloakroom, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Kitchen/ Breakfast Room, Utility Room, Bedroom 1 with En Suite, 2 further Bedrooms, Bathroom, Courtyard Parking, Garage, Garden, Oil C.H The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Situation The Chapter House is a period property with origins dating back some 200 years. This property once part of a large farmhouse is now divided into two dwellings with character features, exposed timbers and open fireplaces with wood burning stoves inset. The moulded covings are particularly attractive especially in the sitting room. The accommodation is set on different levels giving further character to this interesting property. Charlton is a popular residential village with a sample of both period and modern properties, a village green and a local public house. There is an active church. The surrounding countryside is predominantly farming with orchards, arable and market gardening land. Charlton is approximately two miles from Evesham, four miles from Pershore and has the popular villages of Cropthorne and Fladbury which are separated by the Jubilee bridge over the river Avon. The historic town of Evesham lies to the south east of Charlton bordered by the river Avon and the new bridge giving access to this old market town. There are supermarkets and high street shopping, doctors’ surgeries, veterinary surgeries, modern cinema and other excellent facilities in this area. -

The United Kingdom Lesson One: the UK - Building a Picture

The United Kingdom Lesson One: The UK - Building a Picture Locational Knowledge Place Knowledge Key Questions and Ideas Teaching and Learning Resources Activities Interactive: identify Country groupings of ‘British Pupils develop contextual Where is the United Kingdom STARTER: constituent countries of UK, Isles’, ‘United Kingdom’ and knowledge of constituent in the world/in relation to Introduce pupils to blank capital cities, seas and ‘Great Britain’. countries of UK: national Europe? outline of GIANT MAP OF islands, mountains and rivers Capital cities of UK. emblems; population UK classroom display. Use using Names of surrounding seas. totals/characteristics; What are the constituent Interactive online resources http://www.toporopa.eu/en language; customs, iconic countries of the UK? to identify countries, capital landmarks etc. cities, physical, human and Downloads: What is the difference cultural characteristics. Building a picture (PPT) Lesson Plan (MSWORD) Pupils understand the between the UK and The Transfer information using UK Module Fact Sheets for teachers political structure of the UK British Isles and Great laminated symbols to the ‘UK PDF | MSWORD) and the key historical events Britain? Class Map’. UK Trail Map template PDF | that have influenced it. MSWORD UK Trail Instructions Sheet PDF | What does a typical political MAIN ACTIVITY: MSWORD map of the UK look like? Familiarisation with regional UK Happy Families Game PDF | characteristics of the UK MSWORD What seas surround the UK? through ‘UK Trail’ and UK UK population fact sheet PDF | MSWORD Happy Families’ games. What are the names of the Photographs of Iconic Human and Physical Geographical Skills and capital cities of the countries locations to be displayed on Assessment opportunities Geography Fieldwork in the UK? a ‘UK Places Mosaic’. -

The Parish Magazine Takes No Responsibility for Goods Or Services Advertised

Ashton-under-Hill The Beckford Overbury Parish Alstone & Magazine Teddington July 2018 50p Quiet please! Kindly don’t impede my concentration I am sitting in the garden thinking thoughts of propagation Of sowing and of nurturing the fruits my work will bear And the place won’t know what’s hit it Once I get up from my chair. Oh, the mower I will cherish, and the tools I will oil The dark, nutritious compost I will stroke into the soil My sacrifice, devotion and heroic aftercare Will leave you green with envy Once I get up from my chair. Oh the branches I will layer and the cuttings I will take Let other fellows dig a pond, I shall dig a LAKE My garden – what a showpiece! There’ll be pilgrims come to stare And I’ll bow and take the credit Once I get up from my chair. Extracts from ‘When I get Up From My Chair’ by Pam Ayres Schedule of Services for The Parish of Overbury with Teddington, Alstone and Little Washbourne, with Beckford and Ashton under Hill. JULY Ashton Beckford Overbury Alstone Teddington 6.00 pm 11.00 am 1st July 8:00am 9.30 am Evening Family 5th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer Service after Trinity C Parr Clive Parr S Renshaw Lay Team 6.00 pm 11.00 am 9.30 am 8th July 9.30 am Evening Morning Morning 6th Sunday CW HC Worship Prayer Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw R Tett S Renshaw Roger Palmer 11.00 am 6.00 pm 15th July 9.30 am 8.00 am Village Evening 7th Sunday CW HC BCP HC Worship Prayer after Trinity M Baynes M Baynes G Pharo S Renshaw 10.00 am United Parish 22nd July CW HC 8th Sunday & Alstone after Trinity Patronal R Tett 29th July 10:30am 9th Sunday Bredon Hill Group United Worship after Trinity Overbury AUGUST 6.00 pm 5th August 8.00 am 9.30 am Evening 10th Sunday BCP HC CW HC Prayer after Trinity S Renshaw S Renshaw S Renshaw Morning Prayers will be said at 8.30am on Fridays at Ashton. -

GO AVON 2021 Update: Bus Transportation Available!!

Michael Renkawitz, Principal Dr. Diana DeVivo, Assistant Principal David Kimball, Assistant Principal Todd Dyer, Director of School Counseling Timothy P. Filon, Coordinator of Athletics GO AVON! UPDATE August 19, 2021 Dear Class of 2025 and students new to Avon: On August 11 you received an invitation from me to participate in GO AVON!, an orientation program prior to the start of school. We are fortunate that we have a dedicated group of AHS upperclassmen who have planned this orientation session for you. I am thrilled to inform you that bus transportation is now available! Specialty Transportation will begin their morning pick-up at 8:15 a.m. using the revised bus routes listed below. Please note that these revised bus routes will be used on GO AVON! Day only and your child may be picked up/dropped off at a stop different from their regularly assigned bus location used during the school year. Students should take the bus at the nearest bus location listed below. Buses will be shared with Avon MIddle School on this day. AHS students are asked to sit in the back two sections of the bus for cohorting purposes. At dismissal, students will board the same lettered bus as they came on. Please have your child write down the letter of his/her bus, as it will be the same bus that brings your child home. Students will be dropped off along bus routes within 30 minutes of dismissal depending on the route. If you prefer to drive your child, students may be dropped off at AHS no earlier than 8:45 a.m. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Uk Capacity Reserve Limited Bristol Road, Gloucester, Gl2 5Ya

UK CAPACITY RESERVE LIMITED BRISTOL ROAD, GLOUCESTER, GL2 5YA Property Investment Secure RPI income Energy Power Plant INVESTMENT SUMMARY Opportunity to acquire a well let electricity supply plant with RPI uplifts Freehold site extending to approximately 1.5 acres Let to UK Capacity Reserve Limited on an FRI lease from 12th May 2015 and expiring on 11th May 2040 with a tenant’s break clause on 31st December 2033 providing 13 years term certain. Topped up rent of £105,000 pa with upward only RPI uplifts every 5 years. Good covenant strength Offers in excess of £1,450,000 (One Million Four Hundred and Fifty Thousand Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT which reflects a net initial yield of 6.83% after allowing for purchasers’ costs of 6.08% LOCATION The Cathedral City of Gloucester is the administrative centre of the county and lies approximately 104 miles west of London, 55 miles south of Birmingham, 34 miles north of Bristol and 8 miles south west of Cheltenham. Gloucester has good road communications from the A40/A38 with direct access to the M5 at Junction 11, 11a and 12. The M5 provides a continuous motorway link to the M4, M50, M6 and M42. The city has excellent rail services, with the minimum journey time to London Paddington 1 hour 45 minutes. SITUATION The property is positioned off the Bristol Road to the south of Gloucester Town Centre in an established commercial area including car dealerships, trade counter units, self storage, retail warehousing and petrol filling stations PROPERTY COVENANT STRENGTH Freehold site extending to approximately 1.5 acres and let UK Capacity Reserve Limited is a leading provider of flexible to UK Capacity Reserve Limited and utilized as an power capacity to the UK electricity market. -

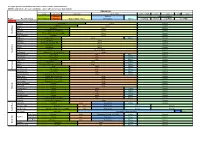

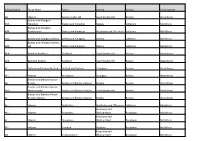

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field.