The Iron Age Tom Moore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays

540 Evesham - Beckford - Bredon - Tewkesbury Astons of Kempsey Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions 1 1 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 1 2 2 1 1 3 3 Greenhill, adj Prince Henry's High School 1545 1540 Evesham, Bus Station (Stand B) 0734 0737 0748 0848 0948 1048 1148 1248 1348 1448 1448 1548 1550 1548 1648 1748 Bengeworth, opp Cemetery 0742 Four Pools, adj Woodlands 0745 Fairfield, opp South Worcestershire College 0748 Fairfield, adj Cheltenham Road 0738 0750 0752 0852 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1452 1552 1554 1552 1652 1752 Hinton Cross, Hinton Cross (S-bound) 0743 0757 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1457 1557 1559 1557 1657 1757 Hinton on the Green, Bevens Lane (N-bound) 1603 1559 Sedgeberrow, Winchcombe Road (SE-bound) 0746 0900 1100 1300 1500 1600 1604 1700 Sedgeberrow, adj Queens Head 0747 0901 1101 1301 1501 1601 1605 1701 Sedgeberrow, opp Churchill Road 0750 0904 1104 1304 1504 1604 1608 1704 Sedgeberrow, adj Hall Farm Drive 0800 1000 1200 1400 1500 1800 Ashton under Hill, opp Cross 0756 0804 0908 1004 1108 1204 1308 1404 1504 1508 1608 1612 1708 1804 Ashton under Hill, adj Cornfield Way 0758 0804 0910 1004 1110 1204 1310 1404 1506 1510 1610 1614 1710 1804 Ashton under Hill, adj Bredon Hill Middle School 0800 0800 1510 Beckford, opp Church 0808 0808 0916 1008 1116 1208 1316 1408 1516 1516 1616 1618 1716 1808 Little Beckford, Cheltenham Road (NE-bound) 0919 1319 Beckford, opp Church 0923 1323 1616 Conderton, opp Shelter -

(PPG) MEETING – 1430 on 3 SEP 19 Present

4 Sep 19 THE ALNEY PRACTICE – PRACTICE PARTICIPATION GROUP (PPG) MEETING – 1430 ON 3 SEP 19 Present: Apologies Philip Tagg (PT) Practice Manager Katherine Holland (KH) Rachael Banfield (RB) Health Care Assistant CCG Jeremy Base (JB) Pamela Dewick (KD) Jennifer Taylor (JT) Geoffrey Gidley (GG) Megan Birchley (MB) Mark Weaver (MW) Ken Newman (KN) Nadia Schneider (NS) Carol Kurylat (CK) Taras Kurylat (TK) Denise Leach (DL) Nicky Milligan (NM) 1. PT welcomed attendees to the meeting and thanked them for expressing an interest in establishing a PPG. He explained the background to the former PPGs for the pre-merger practices: • Cheltenham Road Surgery’s PPG was made up of members of the ‘Friends of Cheltenham Road Surgery’, which was a registered charity with the principal aim of raising funds for the surgery, to be spent to the benefit of its patients. The Friends ceased to operate several years ago when several of the members became too old to continue and there were no volunteers willing to take on committee roles. Subsequent attempts to create a replacement PPG were unsuccessful. • College Yard and Highnam had a PPG, which ceased to be active around the time of the merger. 2. PPGs aim to be representative of the practice population and have a principal aim of meeting on regular basis to discuss the services on offer, and how improvements can be made for the benefit of patients and the practice. This initial meeting aimed to set the scene and agree a way ahead. PT also indicated that as a result of the practice merger we will be liable for a CQC inspection before the end of Mar 20, with the potential that they will wish to speak with the PPG at that time. -

Star House OVERBURY • WORCESTERSHIRE/GLOUCESTERSHIRE BORDER Star House OVERBURY • WORCESTERSHIRE/ GLOUCESTERSHIRE BORDER

Star House OVERBURY • WORCESTERSHIRE/GLOUCESTERSHIRE BORDER Star House OVERBURY • WORCESTERSHIRE/ GLOUCESTERSHIRE BORDER A rare opportunity to purchase a handsome house in a sought after village Sitting/dining room • Study/snug • Kitchen/breakfast room Utility • Cloakroom Master en suite • Three further double bedrooms Family bathroom Parking • Garden and terraces Tewkesbury 6 miles • Cheltenham 10 miles • Worcester 19 miles Birmingham 41 miles • M5 (J9) 5 miles (All distances are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation • Rarely do houses come up for sale in the desirable village of Overbury, which can be found on the Worcestershire/ Gloucestershire border and is predominantly owned by the Overbury Estate. • The village is within the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural beauty on the south side of Bredon Hill, which offers many fine walks and bridle paths. It offers a pre-school nursery, first school, church, village hall, cricket and bowling club and less than half a mile away in Conderton is the Yew Tree public house. • Just over one mile to the west is the charming village of Kemerton, offering further amenities including a village shop, pub, village hall, church and Kemerton Lake Nature Reserve. • Worcester to the north offers a wide range of shopping and recreational facilities including professional rugby at Sixways, horseracing on the banks of the River Severn and cricket in the setting of its Cathedral. Cheltenham to the south offers high street and boutique shopping, excellent restaurants, a theatre and many festivals ranging from literature to jazz and science. -

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013 1 | P a g e CONTENTS ABOUT Ps and Qs ............................................................................................................................... 3 FOR CLARIFICATION ......................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Sustainability ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Key Parish Issues ........................................................................................................................ 9 3. Our Parish .................................................................................................................................. 11 3.1 Our Water ............................................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Our Food ............................................................................................................................... 19 3.3 Our Energy ............................................................................................................................ 26 3.4 Our Waste ............................................................................................................................ -

Baytree Cottage Dumbleton Gloucestershire / Worcestershire Border View to the East Baytree Cottage Dumbleton, Gloucestershire/ Worcestershire Border

Baytree Cottage Dumbleton Gloucestershire / Worcestershire border View to the east Baytree Cottage Dumbleton, Gloucestershire/ Worcestershire border Cheltenham 10 miles, M5 (J9) 7 miles, Birmingham 40 miles, London Paddington (by train) 1 hr 45 mins from Evesham (all mileages approximate) An immaculate, recently extended 3 bedroom cottage with excellent views to Bredon Hill. • Hall • Family bathroom • Sitting/ dining room • Lawned gardens • Kitchen/breakfast room • Outbuilding and wood store • Utility area • Off road parking for • Cloakroom numerous cars • 3 bedrooms • Rural views over farmland Baytree Cottage has just undergone an extensive renovation programme, and has been extended to offer a stunning kitchen breakfast room and an additional bedroom. There is plenty of off road parking and lawned gardens to the front and rear. The kitchen has just been fitted and offers quality Bosch white goods and a range of cupboards and drawers. Baytree Cottage has superb views to Bredon Hill over farmland to the front and a field to the rear. The cottage is constructed of brick under tiled roofs and is attached on one side. A useful brick outbuilding offers generous storage and a wood store. SITUATION AND AMENITIES Baytree is on the northern slopes of Dumbleton Hill between the Cotswold escarpment and Bredon Hill. This area has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and is within the Dumbleton Conservation Area. The village benefits from a fine Norman church and one of the most attractive cricket grounds in Gloucestershire. The cricket clubhouse and the bar can be rented out for parties as it is an ideal setting with a beautiful duck pond and a decked platform. -

The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com Now Available in Paperback Recent & Classic Titles

2017 The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Now available in paperback Recent & Classic Titles & Pax Romana Augustus War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World First Emperor of Rome ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY Renowned scholar Adrian Goldsworthy Caesar Augustus’ story, one of the most turns to the Pax Romana, a rare period riveting in western history, is filled with when the Roman Empire was at peace. A drama and contradiction, risky gambles vivid exploration of nearly two centuries and unexpected success. This biography of Roman history, Pax Romana recounts captures the real man behind the crafted real stories of aggressive conquerors, image, his era, and his influence over two failed rebellions, and unlikely alliances. millennia. “An excellent book. First-rate.” Paper 2015 640 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps —Richard A. Gabriel, Military History 978-0-300-21666-0 $20.00 Paper 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. Cloth 2014 624 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps 978-0-300-23062-8 $22.00 978-0-300-17872-2 $35.00 Hardcover 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. 978-0-300-17882-1 $32.50 Caesar Life of a Colossus Recent & Classic Titles ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY This major new biography by a distin- guished British historian offers a remark- In the Name of Rome ably comprehensive portrait of a leader The Men Who Won the Roman Empire whose actions changed the course of ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY; WITH A NEW PREFACE Western history and resonate some two A world-renowned authority offers a thousand years later. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Archaeological Investigations in St John's, Worcester

Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report No.4 Archaeological Investigations in ST JOHN’S WORCESTER Jo Wainwright Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester (WCM 101591) Jo Wainwright With contributions by Ian Baxter, Hilary Cool, Nick Daffern, C Jane Evans, Kay Hartley, Cathy King, Elizabeth Pearson, Roger Tomlin, Gaynor Western and Dennis Williams Illustrations by Carolyn Hunt and Laura Templeton 2014 Worcestershire Archaeology Research Report no 4 Archaeological Investigations in St John’s, Worcester Published by Worcestershire Archaeology Archive & Archaeology Service, The Hive, Sawmill Walk, The Butts, Worcester. WR1 3PD ISBN 978-0-9929400-4-1 © Worcestershire County Council 2014 Worcestershire ,County Council County Hall, Spetchley Road, Worcester. WR5 2NP This document is presented in a format for digital use. High-resolution versions may be obtained from the publisher. [email protected] Front cover illustration: view across the north-west of the site, towards Worcester Cathedral to previous view Contents Summary ..........................................................1 Background ..........................................................2 Circumstances of the project ..........................................2 Aims and objectives .................................................3 The character of the prehistoric enclosure ................................3 The hinterland of Roman Worcester and identification of survival of Roman landscape -

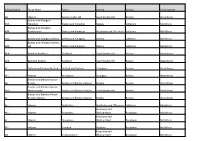

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J.