Phonetics and Phonology of the -Er Suffix in the Hangzhou Wu Chinese Dialect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cantonese Opera and the Growth and Spread Of

Proceedings of the 29th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-29). 2017. Volume 2. Edited by Lan Zhang. University of Memphis, Memphis, TN. Pages 533-544. Historical Change of Diminutives in Southern Wu Dialects Henghua Su Indiana University In many languages, diminutives are formed by adding affixes to the roots, while in different Southern Wu dialects, diminutives take various forms such as suffixation, nasal coda attachment, nasalization and purely tonal change. This paper argues that all these diminutive forms are derived from one single derivational process and the tonal change can be explained in terms of the tonal stability in autosegmental phonology from a historical development perspective. Data from different Southern Wu dialects show that all the diminutive forms presented above are actually derived from one historical changing process. This changing process can be explained with autosegmental representations. Also, geographic distribution of dialects may provide insights for the interactions of phonological features in these dialects. 0. Introduction Autosegmental phonology as a non-linear theory is developed on the discussion of tonal languages in Africa (Kenstowicz 1994). The independent behaviors of tones, such as floating tones and contour tones, provide abundant evidence for a non-linear relationship between tones and the tone bearing units (Clements, 1976. Goldsmith 1976; McCarthy, 1981, 1986; Kenstowicz, 1994; Ogden & Local 1994). Take contour tones as an example, they are best explained by the many-to-one relation between tonal features and TBUs. In a linear theory, this type of phenomenon violates the one-to-one relation between a feature and a segment. Besides African languages, many Asian languages are also tonal. -

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

The Role of the Glottal Stop in Diminutives: an OT Perspective*

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 8.3:639-666, 2007 2007-0-008-003-000168-1 The Role of the Glottal Stop in Diminutives: * An OT Perspective Raung-fu Chung Ming-chung Cheng Southern Taiwan University of Technology National Kaohsiung Normal University In this article, we first sort out the glottal stop patterns in the YBTH diminutives, namely, middle-GSI, final-GSI, and no-GSI (GSI = glottal stop insertion). After further analysis, those varieties in appearance come out essentially with different rankings of the same set of phonological constraints. In the middle-GSI type of dialects, the related phonological constraints work in the ranking order of MAX-IO, ANCHOR-BD(L/R), SON-SEQ, MAX-BD, LINEARITY-BD >> IDENTITY-BD[F], CONTIGUITY-BD, DEP-BD, while in the final-GSI dialects, the order is MAX-IO, ANCHOR-BD(L), CONTIGUITY-BD, SON-SEQ, MAX-BD, IDENTITY-BD[F], LINEARITY-BD >> ANCHOR-BD(R), DEP-BD. The no-GSI type of dialects are unique in that the order of the constraint is ANCHOR-BD(L/R), CONTIGUITY-BD, SON-SEQ, MAX-BD, DEP-BD, IDENTITY-BD[F], LINEARITY-BD >> MAX-IO, which places the MAX-IO in the lowest ranking. It is obvious that MAX-IO, as a constraint of the Faithfulness family, plays a central role for the presence or absence of the glottal stop. When MAX-IO is ranked high, the glottal stop shows up. When it is low, there is no glottal stop. Key words: glottal stop, diminutive, Yuebei Tuhua, optimality theory, output-to-output correspondence (OOC) 1. Introduction This article is an investigation into the role of the glottal stop in the development and formation of diminutives in Chinese dialects in general, and in Yuebei Tuhua (hereafter, YBTH) in particular. -

Research on the Time When Ping Split Into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect

Chinese Studies 2014. Vol.3, No.1, 19-23 Published Online February 2014 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2014.31005 Research on the Time When Ping Split into Yin and Yang in Chinese Northern Dialect Ma Chuandong1*, Tan Lunhua2 1College of Fundamental Education, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, China 2Sichuan Science and Technology University for Employees, Chengdu, China Email: *[email protected] Received January 7th, 2014; revised February 8th, 2014; accepted February 18th, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Ma Chuandong, Tan Lunhua. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Ma Chuandong, Tan Lun- hua. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian. The phonetic phenomenon “ping split into yin and yang” 平分阴阳 is one of the most important changes of Chinese tones in the early modern Chinese, which is reflected clearly in Zhongyuan Yinyun 中原音韵 by Zhou Deqing 周德清 (1277-1356) in the Yuan Dynasty. The authors of this paper think the phe- nomenon “ping split into yin and yang” should not have occurred so late as in the Yuan Dynasty, based on previous research results and modern Chinese dialects, making use of historical comparative method and rhyming books. The changes of tones have close relationship with the voiced and voiceless initials in Chinese, and the voiced initials have turned into voiceless in Song Dynasty, so it could not be in the Yuan Dynasty that ping split into yin and yang, but no later than the Song Dynasty. -

Oujiang Wu Tones and Acoustic Reconstruction

OUJIANG WU TONES AND ACOUSTIC RECONSTRUCTION PHIL ROSE Linguistics (Arts), Australian National University 1. Introduction We do not expect tones, as phonological phenomena, to vary without limit, but to show similarities, or so-called tonological universals, across varieties (Maddieson 1978). Nevertheless, when one samples tones from different Asian tone languages, or even different dialects, they often show a great variety of pitch shapes. Zhu and Rose (1998) for example demonstrated no less than 25 different tones in four varieties from different sub-groups within the Wu dialects of east central China. (I use the term tone in this paper in a sense analogous to phone, that is, as a constellation of audibly different properties, with pitch predominating but also including length and phonation type, that constitutes observation data for phonological – usually tonemic – analysis.) In exploring the nature of phonological variation in Language, we naturally concentrate on differences. This paper, on the other hand, makes use of how similar tones can be. It looks at variation in tones at seven localities distributed over a fairly small geographical area where the varieties, which belong to the same dialectal sub-group, have been described as homogeneous. Although this study reveals some interesting synchronic linguistic-tonetic variation, the main reason for undertaking it is not typological, but, as befits a festschrift for Harold Koch, historical. As mentioned, the Wu dialects of Chinese are well-known for their tonal complexity. Not only do they exhibit probably the most complex tone sandhi in the world (Rose 1990), but they also show a bewildering variety in their citation tones. -

Autonomy of Chinese Judges: Dynamics of People’S Courts, the Ccp and the Public in Contemporary Judicial Reform

AUTONOMY OF CHINESE JUDGES: DYNAMICS OF PEOPLE’S COURTS, THE CCP AND THE PUBLIC IN CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL REFORM by YUE LIU LL.B., Jilin University, 2003 LL.M., Jilin University, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Law) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2016 © Yue Liu, 2016 Abstract This dissertation is the outcome of author’s observations and empirical research on judicial reform in China from the 1980s to 2015. Focusing on judicial decision making process of judges in Chinese courts, it attempts to answer the following questions: How do the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the public, and the internal administrative power—three factors essential to Chinese judges’ judicial decision making process— influence the adjudication of individual cases in various periods of judicial reform? How do the increasingly professionalized judges respond to these institutionalized challenges? Moreover, how do the dynamics generated from the interactions among courts, the CCP, and the public shape the norms and institutional building of judges and courts, and affect judicial reform policies in China? This dissertation adopts historical analysis, documentary analysis, and qualitative analysis to seek answers to these questions. It finds that, first, direct influence of the CCP and the public to the judicial behaviours of individual judges is less evident than indirect influence through the administrative oversight in courts’ internal bureaucracy. Second, the relationships between courts, the CCP, and the public are more dynamic in fragmented China. The norms of Chinese judges’ autonomy and institutional changes in courts are constantly shaped by the expectations and compromise of powers of the CCP, the public, and courts. -

Lesson Plan Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese Nuclear Physicist

Lesson Plan Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese Nuclear Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu assembling an electro-static generator at Smith College Physics Laboratory. Photo courtesy of AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives. Grade Level(s): 9-12 Subject(s): History, Physics In-Class Time: 50-65 minutes Prep Time: 10-15 minutes Materials • A/V equipment • Copies of Chien-Shiung Wu excerpt from The New Dictionary of Scientific Biography (found in the Supplemental Materials) • Copies of Discussion Questions (found in the Supplemental Materials) Prepared by the Center for the History of Physics at AIP 1 Objective In this lesson, students will learn about the life of experimental nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. Born in China, she became a hugely influential subatomic physicist after immigrating to America in the 1930s. Rather than focusing on her scientific accomplishments (which are discussed in more detail in the AIP Teacher’s Guides “Fair or Unfair: Should These Women Have Won Nobel Prizes” and “Outcasts and Opportunities: The Effects of World War II on the Careers of Female Physicists”), this lesson has students read about Chien-Shiung Wu’s early life, education, and unlikely activism. Introduction Chien-Shiung Wu (C.S. Wu) was born near Shanghai, China on May 31, 1912. She attended the Ming De School in her youth, which her father founded as one of the earliest Chinese schools to admit girls. Ultimately in 1930, she enrolled in the National Central University in Nanjing, where four years later she earned her Bachelor of Science degree in physics at the top of her class. 1 Wu’s time at Nanjing coincided with Japan’s invasion of the northern Chinese province Manchuria and subsequent attempts to destabilize the Chinese government. -

浙江大学手册 Hangzhou, China Handbook University of Rhode

浙江大学手册 Zhèjiāng dàxué shǒucè Hangzhou, China Handbook University of Rhode Island Chinese International Engineering Program 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Overview of the city Hangzhou 4 Boost your Chinese Confidence 5 Scholarships 5 Money, Communication 8-11 Time Zone, Weather, Clothing, Packing 11 Upon Arrival 16 Transportation 16 Logistics for Living in China upon Arrival 18 Living 19 Entertainment 20 Shopping 21 Language 22 Zhejiang University Outline 23 Dormitories 23 Classes 24 University Rules 26 Useful Phrases 26 Healthcare 28 Health Vocabulary 29 2 Introduction This guide is meant to be a practical one. It is meant to help prepare you for China and to help give you an idea about how Zhejiang University differs from the University of Rhode Island. This guide will hopefully serve as a base to work from in dealing with these differences. Everyone will have a different experience in China, and as with any school year, it will have its ups and downs. Just work hard, stay healthy, and have a fun learning experience. Do your best to talk to people who have been to China before you go, and to go with an open mind. Go with patience and flexibility (you will need it)! Your time in China is meant to be a time of discovery - a time to discover a new language and culture and a time to learn more about yourself. When you arrive, go out on your own and just observe. Observe how people interact with friends, workers and family. Observe how sales transactions are made. Observe how one orders food in a restaurant. -

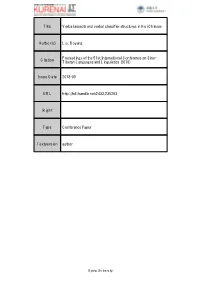

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

The Phonology of Shaoxing Chinese

The Phonology of Shaoxing Chinese Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Trans 10 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl Cover illustration: A mural painting of Emperor Gou Jian of the Yue Kingdom (497-465 B.C.) (present-day Shaoxing). The photo was taken by Xiaonan Zhang in Shaoxing. ISBN 90-76864-90-X NUR 632 Copyright © 2006 by Jisheng Zhang. All rights reserved. The Phonology of Shaoxing Chinese PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. D.D. Breimer, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen en die der Geneeskunde, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 31 januari 2006 klokke 15.15 uur door JISHENG ZHANG geboren te Shaoxing, China in 1955 Promotiecommissie promotor: prof. dr. V.J.J.P. van Heuven co-promotor: dr. J.M. van de Weijer referent: prof. dr. M. Yip (University College London) overige leden: prof. dr. C.J. Ewen dr. M. van Oostendorp (Meertens Instituut) dr. N.S.H. Smith (University of Amsterdam) Dedicated to my mother who gave me my life and brought me up on this ancient land –– Shaoxing. Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................... xi 1 Background............................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction ...............................................................................................1 1.2 Methodology -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help.