When the Saints Go Marching In"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love

Love, Oh Love, Oh Careless Love Careless Love is perhaps the most enduring of traditional folk songs. Of obscure origins, the song’s message is that “careless love” could care less who it hurts in the process. Although the lyrics have changed from version to version, the words usually speak of the pain and heartbreak brought on by love that can take one totally by surprise. And then things go terribly wrong. In many instances, the song’s narrator threatens to kill his or her errant lover. “Love is messy like a po-boy – leaving you drippin’ in debris.” Now, this concept of love is not the sentiment of this author, but, for some, love does not always go right. Countless artists have recorded Careless Love. Rare photo of “Buddy” Bolden Lonnie Johnson New Orleans cornetist and early jazz icon Charles Joseph “Buddy” Bolden played this song and made it one of the best known pieces in his band’s repertory in the early 1900s, and it has remained both a jazz standard and blues standard. In fact, it’s a folk, blues, country and jazz song all rolled into one. Bessie Smith, the Empress of the Blues, cut an extraordinary recording of the song in 1925. Lonnie Johnson of New Orleans recorded it in 1928. It is Pete Seeger’s favorite folk song. Careless Love has been recorded by Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. Fats Domino recorded his version in 1951. Crescent City jazz clarinetist George Lewis (born Joseph Louis Francois Zenon, 1900 – 1968) played it, as did other New Orleans performers, such as Dr. -

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor David Ake, University of Miami Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro Associate Professor Mark Clague © Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik 2016 DEDICATION To Jarvis P. Chuckles, an amalgamation of all those who made this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation was made possible by fellowship support conferred by the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, as well as ample teaching opportunities provided by the Musicology Department and the Residential College. I am also grateful to my department, Rackham, the Institute, and the UM Sweetland Writing Center for supporting my work through various travel, research, and writing grants. This additional support financed much of the archival research for this project, provided for several national and international conference presentations, and allowed me to participate in the 2015 Rackham/Sweetland Writing Center Summer Dissertation Writing Institute. I also remain indebted to all those who helped me reach this point, including my supervisors at the Hatcher Graduate Library, the Music Library, the Children’s Center, and the Music of the United States of America Critical Edition Series. I thank them for their patience, assistance, and support at a critical moment in my graduate career. This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Bruce Boyd Raeburn and his staff at Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive of New Orleans Jazz, and the staff of the Historic New Orleans Collection. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Press Kit Index

PRESS KIT INDEX P.2 DownBeat (**** star review) P.4 JazzTimes P.5 Aberdeen News (Howard Reich Best Of 2011) P.6 NYC Jazz Record P.7 Jazz Journal P.8 Jazz Police P.10 Step Tempest P.12 Financial Times P.13 O's Place P.14 Lucid Culture P.15 MidWest Record P.16 Blog Critics P.19 TMS9-3-jazz P.20 Jazz Magazine (French) P.21 Evasion Mag (French) P.25 Jazz Thing (German) P.26 Jazz Podium (German) !""#$%%&'((")*+,-./*%'0").1+,%234567+,,+8")'17&+'87*).!+17#)1.9 ! ! !"#$!#%%&& "#$%&'()*#+!,(+)! '(()*+,-.! '-.#/$! "#!$%&'())*!+(%*)!! ,%-.!-)/-0&/*!.(1(!&12304!'*5('6*6!1-7*!&/!/%*!8&9-(1-!:-&)(!;(</!(<!/%*!=)-()!+(3)/#! :*'<('0-)>!?'/.!+*)/*'!-)!@&%A!BCDC4!5&E/3'*.!E-&)-./!D*&)FG-5%*1!:-15!63'-)>!/A(! )->%/.!(<!E3'*!-0E'(7-.&/-()C!,%*!<('0*'!:&'-.-&)4!&!B*A!H('I*'!.-)5*!JKKL4!0&6*!%-.! )&0*!A-/%!%-.!&551&-0*6!/'-(!<*&/3'-)>!2&..-./!8'&)M(-.!G(3/-)!&)6!6'300*'!?'-!N(*)->C! N*'*4!:-154!I)(A)!<('!%-.!'*0&'I&21*!/*5%)-O3*!&)6!<()6)*..!<('!/%*!3)E'*6-5/&21*4! &67*)/3'(3.1#!'*-)7*)/.!./&)6&'6.!.35%!&.!P,&I*!/%*!Q?R!,'&-)4S!P"13*!-)!T'**)S!&)6!PU! @*0*02*'!H(34S!/&5I1-)>!+%(E-)R.!PV&1/9!B(C!W!-)!?!G-)('S!&)6!E'*.*)/-)>!&!)302*'! (<!)*A!('->-)&1.!A-/%!*O3&1!E&'/.!.I-114!>3./(!&)6!5'*&/-7-/#C!?1.(!-)5136*6!-.!7-6*(!<'(0!&! E'-7&/*!.*..-()!%*16!63'-)>!/%*!.&0*!*)>&>*0*)/C! :-15!(E*).!%-.!2(16!'*)6-/-()!(<!X3I*!Y11-)>/()R.!P+&'&7&)S!A-/%!&!/%3)6*'(3.!'(&'Z!%*! /%*)!03/*.!&)6!/&E.!%-.!-)./'30*)/R.!./'-)>.4!>(-)>!-)!&)6!(3/!(<!/%*!0*1(6#!&.!%*! &1/*')&/*.!'3021-)>4!&)>31&'!&)6!6*1-5&/*!.()('-/-*.C!?!2'-*<4!*)->0&/-5!'*0&I*!(<!/%*!<(1I! 2&11&6!P$5&'2('(3>%!8&-'S!5()[3'*.!&)!&03.-)>!#*/!.E-)*F5%-11-)>!/%*0*!E&'IZ!.-0-1&'1#! -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Top 12 Soul Jazz and Groove Releases of 2006 on the Soul Jazz Spectrum

Top 12 Soul Jazz and Groove Releases of 2006 on the Soul Jazz Spectrum Here’s a rundown of the Top 12 albums we enjoyed the most on the Soul Jazz Spectrum in 2006 1) Trippin’ – The New Cool Collective (Vine) Imagine a big band that swings, funks, grooves and mixes together R&B, jazz, soul, Afrobeat, Latin and more of the stuff in their kitchen sink into danceable jazz. This double CD set features the Dutch ensemble in their most expansive, challenging effort to date. When you can fill two discs with great stuff and nary a dud, you’re either inspired or Vince Gill. These guys are inspired and it’s impossible to not feel gooder after listening to Trippin.’ Highly recommended. 2) On the Outset – Nick Rossi Set (Hammondbeat) It’s a blast of fresh, rare, old air. You can put Rossi up there on the Hammond B3 pedestal with skilled survivors like Dr. Lonnie Smith and Reuben Wilson. This album is relentlessly grooving, with no ballad down time. If you think back to the glory days of McGriff and McDuff, this “set” compares nicely. 3) The Body & Soul Sessions – Phillip Saisse Trio (Rendezvous) Pianist Saisse throws in a little Fender Rhodes and generally funks up standards and covers some newer tunes soulfully and exuberantly. Great, great version of Steely Dan’s “Do It Again.” Has that feel good aura of the old live Ramsey Lewis and Les McCann sides, even though a studio recording. 4) Step It Up – The Bamboos (Ubiquity) If you’re old enough or retro enough to recall the spirit and heart of old soul groups like Archie Bell and the Drells, these Aussies are channeling that same energy and nasty funk instrumentally. -

NEW ORLEANS 2Nd LINE

PVDFest 2018 presents Jazz at Lincoln Center NEW ORLEANS 2nd LINE Workshop preparation info for teachers. Join the parade! Saturday, June 9, 3:00 - 4:00 pm, 170 Washington Street stage. 4:00 - 5:00 pm, PVDFest parade winds through Downtown, ending at Providence City Hall! PVDFest 2018: a FirstWorks Arts Learning project Table of Contents with Jazz at Lincoln Center A key component of FirstWorks, is its dedication to providing transformative arts experiences to underserved youth across Rhode Island. The 2017-18 season marks the organization’s fifth year of partnership with Jazz at Lincoln Center. FirstWorks is the only organization in Southern New England participating in this highly innovative program, which has become a cornerstone of our already robust Arts Learning program by incorporating jazz as a teaching method for curricular materials. Table of Contents . 2 New Orleans History: Social Aid Clubs & 2nd Lines . 3 Meet Jazz at Lincoln Center . .. 6 Who’s Who in the Band? . 7 Sheet Music . 8 Local Version: Meet Pronk! . 12 Teacher Survey . .. 14 Student Survey. .15 Word Search . .16 A young parade participant hoists a decorative hand fan and dances as the parade nears the end of the route on St. Claude Avenue in New Orleans. Photo courtesy of Tyrone Turner. PVDFest 2018: a FirstWorks Arts Learning project 3 with Jazz at Lincoln Center NOLA History: Social Aid Clubs and 2nd Lines Discover the history of New Orleans second line parades and social aid clubs, an important part of New Orleans history, past and present. By Edward Branley @nolahistoryguy December 16, 2013 Say “parade” to most visitors to New Orleans, and their thoughts shift immediately to Mardi Gras. -

Acoustic Blues Festival Port Townsend Jerron Paxton, Artistic Director

Summer FeStival Schedule CENTRUM creativity in community Fort Worden State Park, Port Townsend July 31–auguSt 7 ACOUSTIC BLUES FESTIVAL PORT TOWNSEND Jerron Paxton, Artistic Director Corey Ledet Supplement to the July 22, 2015 Port Townsend & Jefferson County Leader summer at centrum Hello friends! It is a great pleasure to welcome you all to this Welcome to Centrum’s year’s acoustic blues festival! I have been fortunate to have rd spent the last eight of my 27 years teaching at Centrum. 43 Summer Season! Growing with and learning from this festival has been one of the biggest pleasures of my life. Being made artistic director In partnership with Fort is a great honor. Worden State Park, Centrum serves as a We have plenty of friends and faculty eager to help this year gathering place for creative and it is a safe bet that it’s going to be a hoot. We’re glad you are here to join us! artists and learners of all Blues and the culture surrounding it has been a part of my life since the ages seeking extraordinary beginning. My forebears came from the plantations of Louisiana and Arkansas cultural enrichment. bringing their culture and music with them and instilling it in me. The both OUR MISSION is to foster creative experiences lively and lowdown music that was the soundtrack of their lives should not be that change lives. From exploring the roots of preserved as an old relic, but be kept as alive and vibrant as it was when it was in the blues or jazz, to the traditions of American its heyday. -

Pascack Press

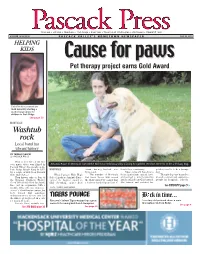

Emerson • Hillsdale • Montvale • Park Ridge • River Vale • Township of Washington • Westwood • Woodcliff Lake VOLUME 14 ISSUE 18 P ASCACK VALLEY’S HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER JULY 26, 2010 HELPING KIDS CauseCausePet therapy project forfor earns pawspaws Gold Award This Girl Scout earned the Gold Award by starting a mentoring program for children in Park Ridge. See page 29 MONTVALE Washtub rock Local band has vibrant history BY THOMAS CLANCEY OF PASCACK PRESS What if we told you the first Amanda Russo of Montvale earned the Girl Scout Gold Award by training her golden retriever, Beckett, to be a therapy dog. ever music video was filmed in Pascack Valley? Specifically, at the MONTVALE Park Ridge Burger King in 1972 friend - her dog, Beckett - was benefit her community. golden retriever to be a therapy by a couple of kids from Pascack by her side. Russo says she has always dog. Hills High School. When Pascack Hills High The member of Montvale been a passionate animal lover Therapy dogs are trained to Then known only as Son of School graduate Amanda Russo Girl Scout Troop 1050 earned and wanted to incorporate that provide comfort and support to the Original Synthetic Hickey earned the highest award in the Gold Award by completing into her Girl Scout Gold Award. people in hospitals, schools, Good Time Rinky-Dink Jug Band, Girl Scouting, manʼs best a 65-hour leadership project to She trained and certified her Inc., and in conjunction with a PHOTO COURTESY JAMIE WATKINS See THERAPY page 94 friendʼs father who was in posses- sion of a 16-millimeter camera, the boys filmed that milestone TIGERS POUNCE B ck in time.. -

The Infinisphere: Expanding Existing Electroacoustic Sound Principles by Means of an Original Design Application Specifically for Trombone

THE INFINISPHERE: EXPANDING EXISTING ELECTROACOUSTIC SOUND PRINCIPLES BY MEANS OF AN ORIGINAL DESIGN APPLICATION SPECIFICALLY FOR TROMBONE BY JUSTIN PALMER MCADARA SCHOLARLY ESSAY Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Jazz Performance in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor James Pugh, Chair and Director of Research Assistant Professor Eli Fieldsteel Professor Erik Lund Professor Charles McNeill DMA Option 2 Thesis and Option 3 Scholarly Essay DEPOSIT COVERSHEET University of Illinois Music and Performing Arts Library Date: July 10, 2020 DMA Option (circle): 2 [thesis] or 3 [scholarly essay] Your full name: Justin Palmer McAdara Full title of Thesis or Essay: The InfiniSphere: Expanding Existing Electroacoustic Sound Principles by Means of an Original Design Application Specifically for Trombone Keywords (4-8 recommended) Please supply a minimum of 4 keywords. Keywords are broad terms that relate to your thesis and allow readers to find your work through search engines. When choosing keywords consider: composer names, performers, composition names, instruments, era of study (Baroque, Classical, Romantic, etc.), theory, analysis. You can use important words from the title of your paper or abstract, but use additional terms as needed. 1. Trombone 2. Electroacoustic 3. Electro-acoustic 4. Electric Trombone 5. Sound Sculpture 6. InfiniSphere 7. Effects 8. Electronic If you need help constructing your keywords, please contact Dr. Bashford, Director of Graduate Studies. Information about your advisors, department, and your abstract will be taken from the thesis/essay and the departmental coversheet.