Streptomycin, 1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Diagnostic Strategies for Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Populations at Risk for Developing Active Disease

Improving diagnostic strategies for latent tuberculosis infection in populations at risk for developing active disease Laura Muñoz López Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Spain License. UNIVERSIDAD DE BARCELONA Facultad de Medicina IMPROVING DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES FOR LATENT TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION IN POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR DEVELOPING ACTIVE DISEASE Memoria presentada por LAURA MUÑOZ LOPEZ Para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicina Barcelona, marzo de 2017 El Dr. Miguel Santín, proFesor asociado de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Barcelona y Médico Adjunto del Servicio de EnFermedades InFecciosas del Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, hace constar que la tesis titulada “Improving diagnostic strategies For latent tuberculosis infection in populations at risk for developing active disease” que presenta la licenciada Laura Muñoz, ha sido realizada bajo su dirección en el campus de Bellvitge de la Facultad de Medicina, la considera Finalizada y autoriza su presentación para que sea deFendida ante el tribunal que corresponda. En Barcelona, marzo de 2017 Dr. Miguel Santín A mis padres A mi gran Familia The research presented in this thesis has been carried out thanks to the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Beca P-FIS 10/00443 AGRADECIMIENTOS Las primeras palabras de agradecimiento son sin duda para el director de esta tesis. Sin las ideas, horas de trabajo y paciencia de Miguel Santín ninguno de los estudios que componen esta tesis, ni por supuesto la propia tesis, hubiesen visto la luz. -

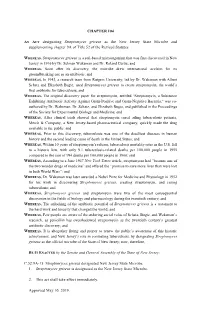

CHAPTER 104 an ACT Designating Streptomyces Griseus As the New

CHAPTER 104 AN ACT designating Streptomyces griseus as the New Jersey State Microbe and supplementing chapter 9A of Title 52 of the Revised Statutes. WHEREAS, Streptomyces griseus is a soil-based microorganism that was first discovered in New Jersey in 1916 by Dr. Selman Waksman and Dr. Roland Curtis; and WHEREAS, Soon after its discovery, the microbe drew international acclaim for its groundbreaking use as an antibiotic; and WHEREAS, In 1943, a research team from Rutgers University, led by Dr. Waksman with Albert Schatz and Elizabeth Bugie, used Streptomyces griseus to create streptomycin, the world’s first antibiotic for tuberculosis; and WHEREAS, The original discovery paper for streptomycin, entitled “Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria,” was co- authored by Dr. Waksman, Dr. Schatz, and Elizabeth Bugie, and published in the Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine; and WHEREAS, After clinical trials showed that streptomycin cured ailing tuberculosis patients, Merck & Company, a New Jersey-based pharmaceutical company, quickly made the drug available to the public; and WHEREAS, Prior to this discovery, tuberculosis was one of the deadliest diseases in human history and the second leading cause of death in the United States; and WHEREAS, Within 10 years of streptomycin’s release, tuberculosis mortality rates in the U.S. fell to a historic low, with only 9.1 tuberculosis-related deaths per 100,000 people in 1955 compared to the rate of 194 deaths per 100,000 people in 1900; and WHEREAS, According to a June 1947 New York Times article, streptomycin had “become one of the two wonder drugs of medicine” and offered the “promise to save more lives than were lost in both World Wars”; and WHEREAS, Dr. -

Selman Waksman and Antibiotics Selman Waksman and Antibiotics

You are here: » American Chemical Society » Education » Explore Chemistry » Chemical Landmarks » Selman Waksman and Antibiotics Selman Waksman and Antibiotics National Historic Chemical Landmark Dedicated May 24, 2005, at Rutgers The State University of New Jersey. Commemorative Booklet (PDF) Waksman and his students, in their laboratory at Rutgers University, established the first screening protocols to detect antimicrobial agents produced by microorganisms. This deliberate search for chemotherapeutic agents contrasts with the discovery of penicillin, which came through a chance observation by Alexander Fleming, who noted that a mold contaminant on a Petri dish culture had inhibited the growth of a bacterial pathogen. During the 1940s, Waksman and his students isolated more than fifteen antibiotics, the most famous of which was streptomycin, the first effective treatment for tuberculosis. Contents Selman Waksman’s Early Years Waksman Moves to America Waksman’s Research on Actinomycetes, and the Search for Antibiotics The Trials of Streptomycin Bringing Streptomycin to Market Controversy over the Discovery of Streptomycin Selman Waksman’s Later Years Research Notes and Further Reading Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments Cite this Page “Selman Waksman and Antibiotics” commemorative booklet produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2005 (PDF). "The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth; and he that is wise will not abhor them." — Ecclesiasticus, xxxviii, 41 Selman Waksman’s Early Life Selman Waksman called his autobiography My Life with the Microbes. That is also the title of the first chapter of the book, which begins "I have devoted my life to the study of microbes, those infinitesimal forms of life which play such important roles in the life of man, animals, and plants. -

Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Author(S): Milton Wainwright Source: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Vol

Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Author(s): Milton Wainwright Source: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 1 (1991), pp. 97-124 Published by: Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn - Napoli Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23330620 Accessed: 17-06-2015 13:54 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23330620?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn - Napoli is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.167.67.179 on Wed, 17 Jun 2015 13:54:00 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hist. Phil. Life Sei., 13 (1991), 97-124 Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Milton Wainwright Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 2TN, England - Abstract The antibiotic streptomycin was discovered soon after penicillin was introduced into medicine. Selman Waksman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery, has since generally been credited as streptomycin's sole discoverer. -

H. BOYD WOODRUFF: CHAMPION of INDUSTRIAL MICROBIOLOGY BOARD of DIRECTORS Meetings President Jan Westpheling

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology January/February/March 2020 V.70 N.1 • www.simbhq.org H. Boyd Woodruff: Champion of Industrial Microbiology 1 .70 2020 January/February/March . N V :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘ ŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 2.993 The Journal of /ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJĂŶĚ ŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ is an international journal which publishes papers in all areas of applied microbiology, e.g., biotechnology, fermentation and cell culture, biocatalysis, environmental microbiology, natural products discovery and biosynthesis, metabolic engineering, genomics, bioinformatics, food microbiology. Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA Special Issue EĂƚƵƌĂůWƌŽĚƵĐƚŝƐĐŽǀĞƌLJĂŶĚ Editors ĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚŝŶƚŚĞ'ĞŶŽŵŝĐƌĂ; Mar. 2019 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium J. Yang, Amgen Inc., Oak Park, CA, USA H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 5 Most Cited Articles of JIMB in 2018: Authors Title Year Cites Katz, Leonard; Baltz, Richard H. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 2016 63 Multiplex gene editing of the zĂƌƌŽǁŝĂůŝƉŽůLJƚŝĐĂgenome using the CRISPR-Cas9 Gao, Shuliang, ĞƚĂů͘ 2016 26 system Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved Baltz, Richard H. -

Genotypic and Epidemiological Characterization of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Complex in Ghana

Genotypic and Epidemiological Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex in Ghana INAUGURALDISSERTATION zur Erlangung der Würde einer Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Adwoa Asante-Poku Wiredu aus Santasi (Ghana) Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch Basel, April 2015 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Sébastien Gagneux und Prof. Dr. Bouke de Jong. Basel, 9th December, 2014 Prof. Dr. Jörg Schibler Dekan ii Table of content Acknowledgment Research Summary List of Tables List of Figures Abbreviations Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. History and global burden TB 1 1.1.1. Historical facts of TB 1 1.1.2. The global burden of TB today 3 1.1.3. TB in Ghana 7 1.2. Causative agent of TB 10 1.3. Mycobacterium africanum 14 1.4. Pathogenesis of TB 19 1.5. Diagnosis and treatment of TB 23 1.5.1. Diagnosis of TB 23 1.5.2. Treatment of TB 28 1.6. Drug resistance 32 1.7. The nature of genetic diversity within MTBC 36 1.8. Genotyping techniques for identification of MTBC 39 1.9. Consequences of genetic diversity within MTBC 46 Chapter 2: Rationale, Goals and Objectives 2.1. Rationale 49 2.2. Goal 50 2.3. Objectives 51 Chapter 3: Drug susceptibility pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Ghana; correlation with clinical response 52 3.1. Abstract 53 3.2. Introduction 55 3.3. Methods 57 iii 3.4. Definitions 58 3.5. Results 61 3.6. Discussion 65 3.7. -

Authorship and Inventorship: an Analysis of Publishing and Patenting Norms and Their Consequences at American Universities Stephanie Chen

Authorship and Inventorship: An analysis of publishing and patenting norms and their consequences at American universities Stephanie Chen Advisor: Robert Cook-Deegan Introduction Norms governing academic science are different from those governing patent law. Yet the two spheres are increasingly in contact, and sometimes conflict, as many academics patent their scientific discoveries. Under U.S. law, patents can be invalidated for omitting inventors. Such omissions can arise from discrepancies between the criteria for authorship and that for inventorship, but they can also arise from illegitimate exclusion of actual inventors. Junior scientists are more likely to be excluded, both by conventional wisdom as well as data-driven analyses.1 A few junior scientists have brought their grievances to court, some with more success than others.2 Recent and ongoing lawsuits between students and their superiors underscore the persisting incongruence between publishing and patenting norms particularly with respect to seniority.3 Even if they are included as inventors, junior scientists have faced discrimination in the patenting process.4 Given the reputational and monetary costs, research universities have an incentive to reconcile the publishing and patenting spheres of academic science. 1 Lissoni, F. et al. “Inventorship and authorship as attribution rights: An enquiry into the economics of scientific credit.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 95, (2013): 46-49; Haeussler, C., Sauermann, H., “Credit where credit is due? The impact of project contributions and social factors on authorship and inventorship.” Research Policy 42(3), 2013: 688-703. 2 For an example of success, see Chou v. University of Chicago, 2000 WL 222638 (N.D Ill. -

Aus Der Fachrichtung Infektionsmedizin

Aus der Fachrichtung Infektionsmedizin Abteilung für Transplantations- und Infektionsimmunologie Der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität des Saarlandes, Homburg Saar Assessment & analysis of HIV/MTB epidemiology and diagnostics as a basis for evidence- based guideline development & priority setting in Europe Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Theoretischen Medizin der Medizinischen Fakultät der UNIVERSITÄT DES SAARLANDES 2012 vorgelegt von Claudia Giehl geboren am 12.12.1974 in Saarbrücken Content 1 Summary ............................................................................................................................. 5 Zusammenfassung ...................................................................................................................... 7 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 The history of tuberculosis in Europe .......................................................................... 9 2.2 The pathogen ............................................................................................................. 11 2.3 Transmission, infection, and immune response........................................................ 12 2.4 Latency ....................................................................................................................... 13 2.5 TB diagnostics ........................................................................................................... -

STATE of NEW JERSEY 218Th LEGISLATURE

[First Reprint] ASSEMBLY, No. 3650 STATE OF NEW JERSEY 218th LEGISLATURE INTRODUCED MARCH 12, 2018 Sponsored by: Assemblywoman ANNETTE QUIJANO District 20 (Union) Assemblywoman PATRICIA EGAN JONES District 5 (Camden and Gloucester) Assemblyman ARTHUR BARCLAY District 5 (Camden and Gloucester) Co-Sponsored by: Assemblyman Houghtaling, Assemblywoman Downey, Assemblymen Dancer, Conaway and Mukherji SYNOPSIS Designates Streptomyces griseus as New Jersey State Microbe. CURRENT VERSION OF TEXT As reported by the Assembly Science, Innovation and Technology Committee on September 17, 2018, with amendments. (Sponsorship Updated As Of: 1/16/2019) A3650 [1R] QUIJANO, JONES 2 1 AN ACT designating Streptomyces 1[Griseus] griseus1 as the New 2 Jersey State Microbe1[,]1 and supplementing chapter 9A of Title 3 52 of the Revised Statutes. 4 5 WHEREAS, Streptomyces 1[Griseus] griseus1 is a soil-based 6 microorganism that was first discovered in New Jersey in 1916 by 7 Dr. Selman Waksman and Dr. Roland Curtis; and 8 WHEREAS, Soon after its discovery, the microbe drew international 9 acclaim for its groundbreaking use as an antibiotic; and 10 WHEREAS, In 1943, a research team from Rutgers University, led by 11 Dr. 1[Selman]1 Waksman with Albert Schatz and Elizabeth Bugie, 12 used Streptomyces 1[Griseus] griseus1 to create streptomycin, the 13 world’s first antibiotic for tuberculosis; and 14 WHEREAS, The original discovery paper for streptomycin, entitled 15 “Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against 16 Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative -

I'll Take Credit for That, Thanks - Science

I'll take credit for that, thanks - Science. By Anjana Ahuja. 25 February 2002 The Times Scientists have been taking the cash and kudos for their students' work for half a century In 1952, the Nobel Prize for Medicine or Physiology went to Selman Waksman, a Rutgers University biologist who discovered the antibiotic streptomycin. To most observers Waksman was a worthy recipient, having found an antibiotic that could wipe out tuberculosis, a leading killer in the Forties. However, to others he was a devious scholar who conveniently failed to credit the work of a junior. The antibiotic had actually been discovered by Albert Schatz, his graduate student, who had toiled for four months in a basement laboratory that Waksman had not visited. Schatz sued for a portion of the royalties on the money-spinning drug that Waksman patented; the courts agreed that he was co-discoverer and awarded him 3 per cent. Waksman took 10 per cent of the royalties. Last year it came to light that a third Rutgers researcher, Elizabeth Bugie, should perhaps also have had her name on the patent and arguably deserved more than the 0.2 per cent royalty she received. The family of Bugie, who died last year, allege that university officials told her: "Some day you'll get married and have a family and it's not important that your name be on the patent." Half a century and many similar cases later, the tradition of misappropriating scientific credit continues to flourish. The most common practice is for senior scientists to put their name to their juniors' research. -

Mycobacterial Species As Case- Study of Comparative Genome Analysis

2012 [SCIENTIFIC PRODUCTION] Doctorat Es Science in Microbiology & Molecular Biology Scientific production 2012 SCIENTIFIC PRODUCTION A- List of international Publications (06): 1. Fathiah ZAKHAM, Lamiae BELAYACHI, Dave USSERY, Mohammed AKRIM, Abdelaziz BENJOUAD, Rajae El AOUAD and Moulay Mustapha ENNAJI. 2011. Mycobacterial species as a case-study of comparative genome analysis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 57 : 1462-1469 . 2. Fathiah ZAKHAM , Halima BAZOUI, Mohammed AKRIM, Sanae LAMRABET, Ouafae LAHLOU, Mohamed EL MZIBRI, Abdelaziz BENJOUAD, My Mustapha ENNAJI and Rajae ELAOUAD. 2012. Evaluation of conventional Molecular diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the clinical specimens from Morocco. J Infect Dev Ctries. 6(1):40-45. 3. Fathiah ZAKHAM , Mohammed AKRIM, Mohamed ELMZIBRI, Abdelaziz BENJOUAD, Rajae ELAOUAD and My Mustapha ENNAJI. 2012 . Rapid Screening and Diagnosis of Tuberculosis: a real Challenge for the mycobacteriologist. Cell. Mol. Biol . 58 : 1632-1640. 4. Fathiah ZAKHAM, Oufae LAHLOU, Mohammed AKRIM, Nada BOUKLATA, Sanae JAOUHARI, Mohamed ELMZIBRI, Abdelaziz BENJOUAD, Mustapha ENNAJI and Rajae ELAOUAD. 2012. Comparison of a DNA based PCR approach with conventional methods for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Morocco . Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 4: (1) 5. Fathiah ZAKHAM , Othmane AOUANE, David USSERY, Abdelaziz BENJOUAD and Mouly Mustapha ENNAJI. 2012. Computational and comparative genomics- proteomics and Phylogeny analysis of twenty one mycobacterial genomes. BMC microbial informatics and experimentation. -

STATE of NEW JERSEY 218Th LEGISLATURE

SENATE, No. 1729 STATE OF NEW JERSEY 218th LEGISLATURE INTRODUCED FEBRUARY 5, 2018 Sponsored by: Senator SAMUEL D. THOMPSON District 12 (Burlington, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean) Co-Sponsored by: Senators Gopal and Diegnan SYNOPSIS Designates Streptomyces griseus as New Jersey State Microbe. CURRENT VERSION OF TEXT As introduced. (Sponsorship Updated As Of: 4/6/2018) S1729 THOMPSON 2 1 AN ACT designating Streptomyces griseus as the New Jersey State 2 Microbe, and supplementing chapter 9A of Title 52 of the 3 Revised Statutes. 4 5 WHEREAS, Streptomyces griseus is a soil-based microorganism that 6 was first discovered in 1916 by Dr. Selman Waksman and Dr. 7 Roland Curtis; and 8 WHEREAS, Soon after its discovery, the microbe drew international 9 acclaim for its groundbreaking use as an antibiotic; and 10 WHEREAS, In 1943, a research team from Rutgers University, led by 11 Dr. Albert Schatz and Dr. Selman Waksman, used Streptomyces 12 griseus to create streptomycin, the world’s first antibiotic for 13 tuberculosis; and 14 WHEREAS, The original discovery paper for streptomycin, entitled 15 “Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against 16 Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria,” was co-authored by 17 Dr. Waksman, Dr. Schatz, and Elizabeth Bugie, and published in 18 the Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and 19 Medicine; and 20 WHEREAS, After clinical trials showed that streptomycin cured ailing 21 tuberculosis patients, Merck & Company, a New Jersey-based 22 pharmaceutical company, quickly made the drug available to the 23 public; and 24 WHEREAS, Prior to this discovery, tuberculosis was one of the 25 deadliest diseases in human history and the second leading cause of 26 death in the United States; and 27 WHEREAS, Within ten years of streptomycin’s release, tuberculosis 28 mortality rates in the U.S.