H. Boyd Woodruff 1917–2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Diagnostic Strategies for Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Populations at Risk for Developing Active Disease

Improving diagnostic strategies for latent tuberculosis infection in populations at risk for developing active disease Laura Muñoz López Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. Spain License. UNIVERSIDAD DE BARCELONA Facultad de Medicina IMPROVING DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES FOR LATENT TUBERCULOSIS INFECTION IN POPULATIONS AT RISK FOR DEVELOPING ACTIVE DISEASE Memoria presentada por LAURA MUÑOZ LOPEZ Para optar al grado de Doctor en Medicina Barcelona, marzo de 2017 El Dr. Miguel Santín, proFesor asociado de la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Barcelona y Médico Adjunto del Servicio de EnFermedades InFecciosas del Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, hace constar que la tesis titulada “Improving diagnostic strategies For latent tuberculosis infection in populations at risk for developing active disease” que presenta la licenciada Laura Muñoz, ha sido realizada bajo su dirección en el campus de Bellvitge de la Facultad de Medicina, la considera Finalizada y autoriza su presentación para que sea deFendida ante el tribunal que corresponda. En Barcelona, marzo de 2017 Dr. Miguel Santín A mis padres A mi gran Familia The research presented in this thesis has been carried out thanks to the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Beca P-FIS 10/00443 AGRADECIMIENTOS Las primeras palabras de agradecimiento son sin duda para el director de esta tesis. Sin las ideas, horas de trabajo y paciencia de Miguel Santín ninguno de los estudios que componen esta tesis, ni por supuesto la propia tesis, hubiesen visto la luz. -

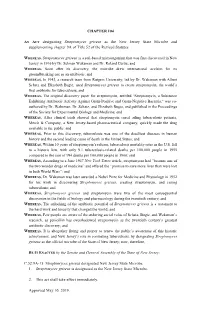

CHAPTER 104 an ACT Designating Streptomyces Griseus As the New

CHAPTER 104 AN ACT designating Streptomyces griseus as the New Jersey State Microbe and supplementing chapter 9A of Title 52 of the Revised Statutes. WHEREAS, Streptomyces griseus is a soil-based microorganism that was first discovered in New Jersey in 1916 by Dr. Selman Waksman and Dr. Roland Curtis; and WHEREAS, Soon after its discovery, the microbe drew international acclaim for its groundbreaking use as an antibiotic; and WHEREAS, In 1943, a research team from Rutgers University, led by Dr. Waksman with Albert Schatz and Elizabeth Bugie, used Streptomyces griseus to create streptomycin, the world’s first antibiotic for tuberculosis; and WHEREAS, The original discovery paper for streptomycin, entitled “Streptomycin, a Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria,” was co- authored by Dr. Waksman, Dr. Schatz, and Elizabeth Bugie, and published in the Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine; and WHEREAS, After clinical trials showed that streptomycin cured ailing tuberculosis patients, Merck & Company, a New Jersey-based pharmaceutical company, quickly made the drug available to the public; and WHEREAS, Prior to this discovery, tuberculosis was one of the deadliest diseases in human history and the second leading cause of death in the United States; and WHEREAS, Within 10 years of streptomycin’s release, tuberculosis mortality rates in the U.S. fell to a historic low, with only 9.1 tuberculosis-related deaths per 100,000 people in 1955 compared to the rate of 194 deaths per 100,000 people in 1900; and WHEREAS, According to a June 1947 New York Times article, streptomycin had “become one of the two wonder drugs of medicine” and offered the “promise to save more lives than were lost in both World Wars”; and WHEREAS, Dr. -

Microbiology Immunology Cent

years This booklet was created by Ashley T. Haase, MD, Regents Professor and Head of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, with invaluable input from current and former faculty, students, and staff. Acknowledgements to Colleen O’Neill, Department Administrator, for editorial and research assistance; the ASM Center for the History of Microbiology and Erik Moore, University Archivist, for historical documents and photos; and Ryan Kueser and the Medical School Office of Communications & Marketing, for design and production assistance. UMN Microbiology & Immunology 2019 Centennial Introduction CELEBRATING A CENTURY OF MICROBIOLOGY & IMMUNOLOGY This brief history captures the last half century from the last history and features foundational ideas and individuals who played prominent roles through their scientific contributions and leadership in microbiology and immunology at the University of Minnesota since the founding of the University in 1851. 1. UMN Microbiology & Immunology 2019 Centennial Microbiology at Minnesota MICROBIOLOGY AT MINNESOTA Microbiology at Minnesota has been From the beginning, faculty have studied distinguished from the beginning by the bacteria, viruses, and fungi relevant to breadth of the microorganisms studied important infectious diseases, from and by the disciplines and sub-disciplines early studies of diphtheria and rabies, represented in the research and teaching of through poliomyelitis, streptococcal and the faculty. The Microbiology Department staphylococcal infection to the present itself, as an integral part of the Medical day, HIV/AIDS and co-morbidities, TB and School since the department’s inception cryptococcal infections, and influenza. in 1918-1919, has been distinguished Beyond medical microbiology, veterinary too by its breadth, serving historically microbiology, microbial physiology, as the organizational center for all industrial microbiology, environmental microbiological teaching and research microbiology and ecology, microbial for the whole University. -

Identification and Nomenclature of the Genus Penicillium

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Dec 20, 2017 Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium Visagie, C.M.; Houbraken, J.; Frisvad, Jens Christian; Hong, S. B.; Klaassen, C.H.W.; Perrone, G.; Seifert, K.A.; Varga, J.; Yaguchi, T.; Samson, R.A. Published in: Studies in Mycology Link to article, DOI: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001 Publication date: 2014 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Visagie, C. M., Houbraken, J., Frisvad, J. C., Hong, S. B., Klaassen, C. H. W., Perrone, G., ... Samson, R. A. (2014). Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Studies in Mycology, 78, 343-371. DOI: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. available online at www.studiesinmycology.org STUDIES IN MYCOLOGY 78: 343–371. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium C.M. -

T'he NEW YEAR -The Annual Meeting

t T'HE NEW YEAR -The Annual Meeting The 19th Annual Meeting of the Society cras held in Ithaca, New York on the campus of Cornell University SBptember 8-10, 1952, in conjunction with meetings of other inember societies of the American Institute of Biological Sciences, The arrangements were excellent. Dr, Charles Chupp, our representative on the AIES committee and Chairman of our Committee on Local Arrangements, along with Dr. P1.F. Barrus, Dr. D, S, Welch, and Dr, Richard Korf who served with him on the Local Committee, are to be especially complimented on the fine arrangeinents that were made for the Society, The majority of our members were housed in IJillard Straight Hall since many had arrived early to attend the Annual Foray, The program carried the titles of 77 papers resulting from original research and three special features; the Presidential Address by Dr, J. C, Gilman on "The Pure Culture in Taxonomyu, The Third Annual Lecture of .the Mycological Society of America by Dr. Benjamin M, Duggar who spoke on llCharacteristic of Certain Selected Species of Actinomycetesll and a symposium on "Physiology of Fungit1 which was sponsored jointly by the Bociety and the ~licrobiolo~icalSection of the Botanical Society of Aaerica. Most of our pcper-reading sessions were joint sessions also with the ~ficrobiological Sction, The concensus seemed to be that this could be looked upon as one of our outstanding annual meetings, A11 sessions were well attended, At the business meeting on Monday September 8th, the Society approved a number of recomflendations of the Council as presented in the Council Report. -

Species-Specific PCR to Describe Local-Scale Distributions of Four

fungal ecology 6 (2013) 419e429 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funeco Species-specific PCR to describe local-scale distributions of four cryptic species in the Penicillium 5 chrysogenum complex Alexander G.P. BROWNE*, Matthew C. FISHER, Daniel A. HENK* Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Penicillium chrysogenum is a ubiquitous airborne fungus detected in every sampled region of Received 2 October 2012 the Earth. Owing to its role in Alexander Fleming’s serendipitous discovery of Penicillin in Revision received 8 March 2013 1928, the fungus has generated widespread scientific interest; however its natural history is Accepted 13 March 2013 not well understood. Research has demonstrated speciation within P. chrysogenum, Available online 15 June 2013 describing the existence of four cryptic species. To discriminate the four species, we Corresponding editor: developed protocols for species-specific diagnostic PCR directly from fungal conidia. 430 Gareth W. Griffith Penicillium isolates were collected to apply our rapid diagnostic tool and explore the dis- tribution of these fungi across the London Underground rail transport system revealing Keywords: significant differences between Underground lines. Phylogenetic analysis of multiple type Alexander Fleming isolates confirms that the ‘Fleming species’ should be named Penicillium rubens and that London Underground divergence of the four ‘Chrysogenum complex’ fungi occurred about 0.75 million yr ago. Mycology Finally, the formal naming of two new species, Penicillium floreyi and Penicillium chainii,is Penicillium chrysogenum performed. Phylogeny ª 2013 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Taxonomy Introduction In Sep. -

Society for Industrial Microbiology Christine L

SIM—p. 1 Society for Industrial Microbiology Christine L. Case, Ed. D. Microbiology Professor Skyline College/San Bruno CA Society for Industrial Microbiology Director, 1996—1999 Robert Schwartz, Ph. D. Abbott Laboraties/North Chicaco IL Society for Industrial Microbiology Fellow and President, 1991—1992 Published in In M. C. Flickinger and S. W. Drew (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Bioprocess Technology,pp. 2120- 2124. John Wiley, 1999.. The Society for Industrial Microbiology (SIM) is a develop after Pasteur’s initial experiments, probably non–profit professional association dedicated to the due to the lack of good culture methods and advancement of applied microbiological sciences, selective media. In the late 1800s, Jokichi Takamine especially as they apply to industrial products, brought the Koji process for producing amylase to biotechnology, materials, and processes. In 1996, the United States. He received the first U.S. patent the Board of Directors recommended to the on an enzyme production process and established membership to change the Society’s name to the the first fermentation company in the United States. Society for Industrial Microbiology and (1) Except for a few outstanding contributions Biotechnology. This change reflects the careers and mainly involving lactic acid, acetone–butanol technologies that have developed since the 1980s fermentations, and production of yeast and yeast and will be put to a vote by membership. A primary products, industrial microbiology did not progress objective of SIM is to serve as a liaison between the very rapidly until after 1900. In 1896 at the various specialized fields of applied microbiology. It Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Samuel C. -

Deconstructing the Fable of the Discovery of Penicillin By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository La Moisissure et la Bactérie: Deconstructing the Fable of the Discovery of Penicillin by Ernest Duchesne Gilbert Shama Department of Chemical Engineering. Loughborough University Loughborough Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, UK. +44 1509 222514 [email protected] Abstract: Ernest Duchesne (1874–1912) completed his thesis on microbial antagonism in 1897 in Lyon. His work lay unknown for fifty years, but on being brought to light led to his being credited with having discovered penicillin prior to Alexander Fleming. The claims surrounding Duchesne are examined here both from the strictly microbiological perspective, and also for what they reveal about how the process of discovery is frequently misconstrued. The combined weight of evidence presented here militates strongly against the possibility that the species of Penicillium that Duchesne worked with produced penicillin. Keywords: Ernest Duchesne, Penicillin, Alexander Fleming, Penicillium 1 Introduction Following the appearance of an article on penicillin in The Times of London in the summer of 1942,1 Almroth Wright, head of the inoculation department at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, wrote to the editor concerning a colleague of his—a certain Alexander Fleming. In his letter, Wright pointed out that the newspaper had “refrained from putting the laurel wreath around anybody’s brow for [penicillin’s] discovery” and that “on the principle of palmam qui meruit ferat (let him bear the palm who has earned it) it should be decreed to Professor Fleming.”2 A number of commentators over the seventy years or so that have elapsed since the publication of this letter have sought to remove—snatch even—the wreath from Alexander Fleming’s brow and award it elsewhere. -

Selman Waksman and Antibiotics Selman Waksman and Antibiotics

You are here: » American Chemical Society » Education » Explore Chemistry » Chemical Landmarks » Selman Waksman and Antibiotics Selman Waksman and Antibiotics National Historic Chemical Landmark Dedicated May 24, 2005, at Rutgers The State University of New Jersey. Commemorative Booklet (PDF) Waksman and his students, in their laboratory at Rutgers University, established the first screening protocols to detect antimicrobial agents produced by microorganisms. This deliberate search for chemotherapeutic agents contrasts with the discovery of penicillin, which came through a chance observation by Alexander Fleming, who noted that a mold contaminant on a Petri dish culture had inhibited the growth of a bacterial pathogen. During the 1940s, Waksman and his students isolated more than fifteen antibiotics, the most famous of which was streptomycin, the first effective treatment for tuberculosis. Contents Selman Waksman’s Early Years Waksman Moves to America Waksman’s Research on Actinomycetes, and the Search for Antibiotics The Trials of Streptomycin Bringing Streptomycin to Market Controversy over the Discovery of Streptomycin Selman Waksman’s Later Years Research Notes and Further Reading Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments Cite this Page “Selman Waksman and Antibiotics” commemorative booklet produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2005 (PDF). "The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth; and he that is wise will not abhor them." — Ecclesiasticus, xxxviii, 41 Selman Waksman’s Early Life Selman Waksman called his autobiography My Life with the Microbes. That is also the title of the first chapter of the book, which begins "I have devoted my life to the study of microbes, those infinitesimal forms of life which play such important roles in the life of man, animals, and plants. -

Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Author(S): Milton Wainwright Source: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Vol

Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Author(s): Milton Wainwright Source: History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 1 (1991), pp. 97-124 Published by: Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn - Napoli Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23330620 Accessed: 17-06-2015 13:54 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23330620?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn - Napoli is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.167.67.179 on Wed, 17 Jun 2015 13:54:00 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hist. Phil. Life Sei., 13 (1991), 97-124 Streptomycin: Discovery and Resultant Controversy Milton Wainwright Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S10 2TN, England - Abstract The antibiotic streptomycin was discovered soon after penicillin was introduced into medicine. Selman Waksman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery, has since generally been credited as streptomycin's sole discoverer. -

H. BOYD WOODRUFF: CHAMPION of INDUSTRIAL MICROBIOLOGY BOARD of DIRECTORS Meetings President Jan Westpheling

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology January/February/March 2020 V.70 N.1 • www.simbhq.org H. Boyd Woodruff: Champion of Industrial Microbiology 1 .70 2020 January/February/March . N V :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘ ŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 2.993 The Journal of /ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJĂŶĚ ŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ is an international journal which publishes papers in all areas of applied microbiology, e.g., biotechnology, fermentation and cell culture, biocatalysis, environmental microbiology, natural products discovery and biosynthesis, metabolic engineering, genomics, bioinformatics, food microbiology. Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA Special Issue EĂƚƵƌĂůWƌŽĚƵĐƚŝƐĐŽǀĞƌLJĂŶĚ Editors ĞǀĞůŽƉŵĞŶƚŝŶƚŚĞ'ĞŶŽŵŝĐƌĂ; Mar. 2019 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium J. Yang, Amgen Inc., Oak Park, CA, USA H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 5 Most Cited Articles of JIMB in 2018: Authors Title Year Cites Katz, Leonard; Baltz, Richard H. Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 2016 63 Multiplex gene editing of the zĂƌƌŽǁŝĂůŝƉŽůLJƚŝĐĂgenome using the CRISPR-Cas9 Gao, Shuliang, ĞƚĂů͘ 2016 26 system Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved Baltz, Richard H. -

Charles Thom

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES C H A R L E S T HOM 1872—1956 A Biographical Memoir by KE N N E T H B . RAPER Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1965 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. CHARLES THOM November 11,1872-May 24,1956 BY KENNETH B. RAPER ITH THE DEATH of Charles Thom on May 24, 1956, at his Whome in Port Jefferson, New York, the nation lost one of its most colorful and most productive microbiologists. For more than half a century he was a consistent contributor to micro- biological literature, and during the course of his career he contributed much to the basic science in this field and to the practical application of microorganisms in agriculture and industry. While he was best known for his monumental studies on two genera of molds, Aspergillus and Penicillium, he was at home in the dairy, the canning factory, and the cotton field as well. His interests in biology stemmed from his boy- hood on the farm and from his early contacts with outstanding biologists who instilled in him an unquenchable zeal for the study of living systems, large and small. The pattern of his scientific work was determined in substantial part by the vari- ous official positions which he held in the United States Depart- ment of Agriculture from 1904 to 1942, but sustained by an The writer was closely associated with Dr.