Mis-Use of Pahlavi Public Monuments and Their Iranianreclaim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and Dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract

Date:12/1/18 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and Homer's Iliad are among the first literary masterpieces of Iran and Greece. These teachings include the educational teachings of Zal and Roudabeh, and Paris and Helen. This paper presents a comparative look at the immortal effect of this Iranian poet with Homer's poem-- the Greek blind poet. In this comparison, using a content analysis method, the effects of the educational teachings of these two stories are extracted and expressed, The results of this study show that the human and universal educational teachings of Shahnameh are far more than that of Homer's Iliad. Keywords: teachings, education,analysis,Shahname,Iliad. Introduction The literature of every nation is a mirror of the entirety of thought, culture and customs of that nation, which can be expressed in elegance and artistic delicacy in many different ways. Shahnameh and Iliad both represent the literature of the two peoples of Iran and Greece, which contain moral values for the happiness of the individual and society. "The most obvious points of Shahnameh are its advice and many examples and moral commands. To do this, Ferdowsi has taken every opportunity and has made every event an excuse. Even kings and warriors are used for this purpose. "Comparative literature is also an important foundation for the exodus of indigenous literature from isolation, and it will be a part of the entire literary heritage of the world, exposed to thoughts and ideas, and is also capable of helping to identify contemplation legacies in the understanding and friendship of the various nations."(Ghanimi, 44: 1994) Epic literature includes poems that have a spiritual aspect, not an individual one. -

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected]

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Introduction Studying the roots of a particular literary history enables us to better understand the allusions the literature transmits and why we appreciate them. It also allows us to foresee how the literature may progress.1 I will try to keep this attitude in the reader’s mind in offering this brief summary of medieval Persian literature, a formidable task considering the variety and wealth of the texts and documentation on the subject.2 In this study we will pay special attention to the development of the Persian literature over the last millennia, focusing in particular on the initial development and background of various literary genres in Persian. Although the concept of literary genres is rather subjective and unstable,3 reviewing them is nonetheless a useful approach for a synopsis, facilitating greater understanding, deeper argumentation, and further speculation than would a simple listing of dates, titles, and basic biographical facts of the giants of Persian literature. Also key to literary examination is diachronicity, or the outlining of literary development through successive generations and periods. Thriving Persian literature, undoubtedly shaped by historic events, lends itself to this approach: one can observe vast differences between the Persian literature of the tenth century and that of the eleventh or the twelfth, and so on.4 The fourteenth century stands as a bridge between the previous and the later periods, the Mongol and Timurid, followed by the Ṣafavids in Persia and the Mughals in India. Given the importance of local courts and their support of poets and writers, it is quite understandable that literature would be significantly influenced by schools of thought in different provinces of the Persian world.5 In this essay, I use the word literature to refer to the written word adeptly and artistically created. -

Compare and Analyzing Mythical Characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh

WALIA journal 31(S4): 121-125, 2015 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Compare and analyzing mythical characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh Mohammadtaghi Fazeli 1, Behrooze Varnasery 2, * 1Department of Archaeology, Shushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shushtar, Iran 2Department of Persian literature Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Iran Abstract: The content difference in both works are seen in rhetorical Science, the unity of epic tone ,trait, behavior and deeds of heroes and Kings ,patriotism in accordance with moralities and their different infer from epic and mythology . Their similarities can be seen in love for king, obeying king, theology, pray and the heroes vigorous and physical power. Comparing these two works we concluded that epic and mythology is more natural in the Epic of the king than Garshaseb Nameh. The reason that Ferdowsi illustrates epic and mythological characters more natural and tangible is that their history is important for him while Garshaseb Nameh looks on the surface and outer part of epic and mythology. Key words: The epic of the king;.Epic; Mythology; Kings; Heroes 1. Introduction Sassanid king Yazdgerd who died years after Iran was occupied by muslims. It divides these kings into *Ferdowsi has bond thought, wisdom and culture four dynasties Pishdadian, Kayanids, Parthian and of ancient Iranian to the pre-Islam literature. sassanid.The first dynasties especially the first one Garshaseb Nameh has undoubtedly the most shares have root in myth but the last one has its roots in in introducing mythical and epic characters. This history (Ilgadavidshen, 1999) ballad reflexes the ethical and behavioral, trait, for 4) Asadi Tusi: The Persian literature history some of the kings and Garshaseb the hero. -

3/1980 Report

MARCH 1980 SURVEY March 28, 1980 Surveyso fConsume rAttitude s Richard T.Curtin , Director §> CONSUMER SENTIMENT FALLS TO NEW RECORD LOW LEVEL **In the March 1980 survey, the Index of Consumer Sentiment was 56.5,dow n more than 10 Index-points from February 1980 (66.9) and March 1979 (68.4), and represents the lowest level recorded in more than a quarter-century. At no time have consumers been more pessimistic about their ownpersona l financial situation or about prospects for the economy as a whole. Importantly, the major portion of these declines were recorded prior to President Carter's latest inflation message just 10 percent of the interviews were conducted after Carter's speech. **Among families with incomes of $15,000 and over, the Index of Consumer Senti ment was 51.3 in March 1980,dow n from 60.2 in February 1980, and 65.2i n March 1979. TheMarc h 1980 Index figure of 51.3 is below the prior record low of 53.6 recorded in February 1975. **New record low levels recorded in March 1980include : *Near1y half (48 percent) of all families reported in March 1980 that they were worse off financially than a year earlier, twice the propor tion whoreporte d an improved financial situation (24 percent). *Three-in-four respondents (76 percent) expected bad times financially for the economy as a whole during the next 12 months, while just 14 percent expected improvement. ^Interest rates were expected to increase during the next 12 months by 71 percent of all families in March 1980an d the highest rates of expected inflation were recorded during early 1980, with consumers expecting inflation to average 12% during the next 12 months. -

GENERAL AGREEMENT on 1 April 1980 TARIFFS and TRADE Limited Distribution

RESTRICTED L/4914/Rev.1 GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 1 April 1980 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution MULTILATERAL TRADE NEGOTIATIONS Status of Acceptances of Protocols, Agreements and Arrangements (as of 31 March 1980) The following Protocols, Agreements and Arrangements have been accepted by the Governments listed on the dates and with the conditions specified. A. Geneva (1979) Protocol to the General.Agreement on Tariffs and Trade - Argentina 11 July 1979 - Austria subjectt to ratification) 17 October 1979 Ratification 28 December 1979 - Belgium (Subject to ratification) 17 December 1979 - Canada (subject to ratification) 11 July 1979 - Denmark (subject to ratification). 17 December 1979 Ratification with regard to the products 21 December 1979 subject to the regime of the European Coal and Steel Community and except as regards its application to the Faroe Islands. - European Economic Community 13 July 1979 (For authentification of the Protocol and of the schedules of tariff concessions annexed thereto, and subject to conclusion by the European Communities in accordance with the procedures in force) Acceptance 17 December 1979 - Finland (subject to ratification) 11 July 1979 Ratification 13 March 1980 - France 17 December 1979 - Germany, Fed. Rep. (subject to ratification) 17 December 1979 - Hungary 17 December 1979 - Iceland (subject to ratification) 18 September 1979 - Ireland 17 December 1979 - Israel (subject to ratification) 22 November 1979 - Italy 17 December 1979 - Jamaica 12 December 1979 - Japan (subject to acceptance) 27 July 1979 - Luxembourg 17 December 1979 L/4914/Rev.1 Page 2 - Netherlands 17 December 1979 The acceptance shall apply to the Kingdom in Europe only. However, the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands reserves the right to extend the acceptance of the-Protocol by written notification to the Netherlands Antilles at a later date. -

Shiraz Dissertation Full 8.2.20. Final Format

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO The Shiraz Arts Festival: Cultural Democracy, National Identity, and Revolution in Iranian Performance, 1967-1977 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In Music By Joshua Jamsheed Charney Committee in charge: Professor Anthony Davis, Co-Chair Professor Jann Pasler, Co-Chair Professor Aleck Karis Professor Babak Rahimi Professor Shahrokh Yadegari 2020 © Joshua Jamsheed Charney, 2020 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Joshua Jamsheed Charney is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Co-chair _____________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2020 iii EPIGRAPH Oh my Shiraz, the nonpareil of towns – The lord look after it, and keep it from decay! Hafez iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………… iii Epigraph…………………………………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………… v Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………… vii Vita………………………………………………………………………………. viii Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………… ix Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 1: Festival Overview …………………………………………………… 17 Chapter 2: Cultural Democracy…………………………………………………. -

Feminist Criticism of the Story of Homay Chehrzad's Kingdom in Shahnameh

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 2, No. 9, pp. 1980-1986, September 2012 © 2012 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.2.9.1980-1986 Feminist Criticism of the Story of Homay Chehrzad's Kingdom in Shahnameh Mohammad Behnamfar Birjand University, Iran Email: [email protected] Homeira Alizadeh Garmabesofla Birjand University, Iran Email: [email protected] Effat Fareq Birjand University, Iran Email: [email protected] Abstract—Feminism is a movement for the defense of women's rights and eliminating racial discrimination of all kinds and also it causes the women to be present in community like men. The aim of this kind of critique is that women present a definition of their own state and save themselves from the dominance of men. Also, this critique engages in women's issues in literary texts and studies a literary work either in terms of its author's sex or female characters existing in that work. In this paper, we try to study the feminist critique of Homay Chehrzad Kingdom story in Shahnameh Ferdowsi in terms of female characters created in the story. The results of this study are obtained according to the content analysis. The conducted results show that although women have been respected in the story but there is still cases of oppression and humiliation of men towards them. On the other hand, existence of the second wave of feminism which emphasizes on the masculine traits and characteristics and examples of the third wave, which is the incidence of maternal sentiment, is evident in this story. -

US Covert Operations Toward Iran, February-November 1979

This article was downloaded by: [Tulane University] On: 05 January 2015, At: 09:36 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Middle Eastern Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fmes20 US Covert Operations toward Iran, February–November 1979: Was the CIA Trying to Overthrow the Islamic Regime? Mark Gasiorowski Published online: 01 Aug 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Mark Gasiorowski (2015) US Covert Operations toward Iran, February–November 1979: Was the CIA Trying to Overthrow the Islamic Regime?, Middle Eastern Studies, 51:1, 115-135, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2014.938643 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2014.938643 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Death of an Emperor €“ Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi

The death of an emperor – Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and his political cancer Khoshnood, Ardavan; Khoshnood, Arvin Published in: Alexandria Journal of Medicine DOI: 10.1016/j.ajme.2015.11.002 2016 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Khoshnood, A., & Khoshnood, A. (2016). The death of an emperor – Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and his political cancer. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 52(3), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2015.11.002 Total number of authors: 2 Creative Commons License: CC BY-NC-ND General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 02. -

Maps Cited by Congress When Designating Wilderness

Maps Summary Table In 2003 long-time NPS Wilderness Coordinator Wes Henry prepared this table that was intended for inclusion in the updated Reference Manual 41 – Wilderness Management. Wes died soon thereafter. PEER has updated the table to reflect information through 2014. RM 41: Section F: DRAFT January 21, 2003 Maps Cited by Congress when Designating Wilderness. The table lists in: Column 2: maps cited by Congress when designating NPS wilderness (in chronological order by date of enactment); Column 3: date of an official legal description prepared after designation, and Column 4: whether a post-enactment official boundary map was prepared. NPS AREA – CONGRESSIONAL DATE OF DATE OF WILDERNESS MAP NUMBER OFFICIAL OFFICAL MAP DATE AND DATE, CITED LEGAL IN LAW DESCRIPTION Craters of the 131-91,000 December 1970 NPS cited Moon – Oct. 1970 March 1970 legislative map Petrified Forest - NP-PF-3320-O December 1970 NPS cited October 1970 November 1967 legislative map Lava Beds – NM-LB-3227H December 1972 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Lassen Volcanic – NP-LV-9013C June 1973 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Point Reyes – 612-90,000-B May 1978 February 1977 October 1976 September 1976 Bandelier – 315-20,014-B August 1978 August 1978 October 1976 May 1976 Black Canyon of 144-20,017 January 1977 January 1977 the Gunnison – May 1973 October 1976 Chiricahua - 145-20,007-A May 1978 January 1977 October 1976 September 1973 Great Sand Dunes 140-20,006-C December 1976; January 1980 October 1976 February 1976 Revised: -

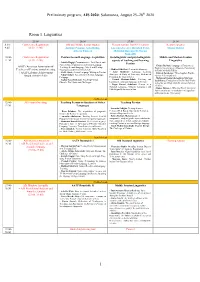

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala